William Morris In The East End

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

William Morris spoke at Speakers’ Corner in Victoria Park on 26th July & 11th October 1885, 8th August 1886, 27th March & 21st May 1888

If you spotted someone hauling an old wooden Spitalfields Market orange crate around the East End, that was me undertaking a pilgrimage to some of the places William Morris spoke in the hope he might return for one last oration.

The presence of William Morris in the East End is almost forgotten today. Yet he took the District Line from his home in Hammersmith regularly to speak here through the last years of his life, despite persistent ill-health. Ultimately disappointed that the production of his own designs had catered only to the rich, Morris dedicated himself increasingly to politics and in 1884 he became editor of The Commonweal, newspaper of the Socialist League, using the coach house at Kelsmcott House in Hammersmith as its headquarters.

As an activist, Morris spoke at the funeral of Alfred Linnell, who was killed by police during a free speech rally in Trafalgar Sq in 1887, on behalf of the Match Girls’ Strike in 1888 and in the Dock Strike of 1889. His final appearance in the East End was on Mile End Waste on 1st November 1890, on which occasion he spoke at a protest against the brutal treatment of Jewish people in Russia.

When William Morris died of tuberculosis in 1896, his doctor said, ‘he died a victim to his enthusiasm for spreading the principles of Socialism.’ Morris deserves to be remembered for his commitment to the people of the East End in those years of political turmoil as for the first time unions struggled to assert the right to seek justice for their workers.

8th April 1884, St Jude’s Church, Commercial St – Morris gave a speech at the opening of the annual art exhibition on behalf of Vicar Samuel Barnett who subsequently founded Toynbee Hall and the Whitechapel Gallery.

During 1885, volunteers distributed William Morris’ What Socialists Want outside the Salmon & Ball in Bethnal Green

1st September 1885, 103 Mile End Rd

20th September 1885, Dod St, Limehouse – When police launched a violent attack on speakers of the Socialist League who defended the right to free speech at this traditional spot for open air meetings, William Morris spoke on their behalf in court on 22nd September in Stepney.

10th November 1886 & 3rd July 1887, Broadway, London Fields

November 20th 1887, Bow Cemetery – Morris spoke at the burial of Alfred Linnell, a clerk who was killed by police during a free speech rally in Trafalgar Sq. ‘Our friend who lies here has had a hard life and met with a hard death, and if our society had been constituted differently his life might have been a delightful one. We are engaged in a most holy war, trying to prevent our rulers making this great town of London into nothing more than a prison.’

9th April 1889, Toynbee Hall, Commercial St – Morris gave a magic lantern show on the subject of ‘Gothic Architecture’

1st November 1890, Mile End Waste – Morris spoke in protest against the persecution of Jews in Russia

William Morris in the East End

3rd January & 27th April 1884, Tee-To-Tum Coffee House, 166 Bethnal Green Rd

8th April 1884, St Jude’s Church, Commercial St

29th October 1884, Dod St, Limehouse

9th November 1884, 13 Redman’s Row

11th January & 12th April 1885, Hoxton Academy Schools

29th March 24th May 1885, Stepney Socialist League, 110 White Horse St

26th July & 11th October 1885, Victoria Park

8th August 1885, Socialist League Stratford

16th August 1885, Exchange Coffee House, Pitfield St, Hoxton

1st September 1885, Swaby’s Coffee House, 103 Mile End Rd

22nd September 1885, Thames Police court, Stepney (Before Magistrate Sanders)

24th January 1886, Hackney Branch Rooms, 21 Audrey St, Hackney Rd

2nd February 1886, International Working Men’s Educational Club, 40 Berners St

5th June 1886, Socialist League Stratford

11th July 1886, Hoxton Branch of the Socialist League, 2 Crondel St

24th August 1886, Socialist League Mile End Branch, 108 Bridge St

13th October 1886, Congregational Schools, Swanscombe St, Barking Rd

10th November 1886, Broadway, London Fields

6th March 1887, Hoxton Branch of the Socialist League, 2 Crondel St

13th March & 12th June 1887, Hackney Branch Rooms, 21 Audrey St, Hackney Rd

27th March 1887, Borough of Hackney Club, Haggerston

27th March, 21st May, 23rd July, 21st August & 11th September, 1887 Victoria Park

24th April 1887, Morley Coffee Tavern Lecture Hall, Mare St

3rd July 1887, Broadway, London Fields

21st August 1887, Globe Coffee House, High St, Hoxton

25th September 1887, Hoxton Church

27th September 1887, Mile End Waste

18th December 1887, Bow Cemetery, Southern Grove

17th April 1888, Mile End Socialist Hall, 95 Boston St

17th April 1888, Working Men’s Radical Club, 108 Bridge St, Burdett Rd

16th June 1888, International Club, 23 Princes Sq, Cable St

17th June 1888, Victoria Park

30th June 1888, Epping Forest Picnic

22nd September 1888, International Working Men’s Education Club, 40 Berners St

9th April 1889, Toynbee Hall, Commercial St

27th June 1889, New Labour Club, 5 Victoria Park Sq, Bethnal Green

8th June 1889, International Working Men’s Education Club, 40 Berners St

1st November 1890, Mile End Waste

This feature draws upon the research of Rosemary Taylor as published in her article in The Journal of William Morris Studies. Click here to join the William Morris Society

You may also like to read about

Pollock’s Toy Theatres In Spitalfields

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

Next weekend, Pollock’s Toy Theatres return to their roots with a two day pop up at House of Annetta in Spitalfields including performances, workshops and an exhibition. Below you can read my account of the origin of the nineteenth century toy theatre movement in the East End.

William Webb, 49 Old St, 1857

William Webb, 49 Old St, 1857

These days, Old St is renowned for its digital industries but – for over a hundred years – this area was celebrated as the centre of toy theatre manufacture in London. Formerly, these narrow streets within walking distance of the City of London were home to highly skilled artisans who could turn their talents to the engraving, printing, jewellery, clock, gun and instrument-making trades which operated here – and it was in this environment that the culture of toy theatres flourished.

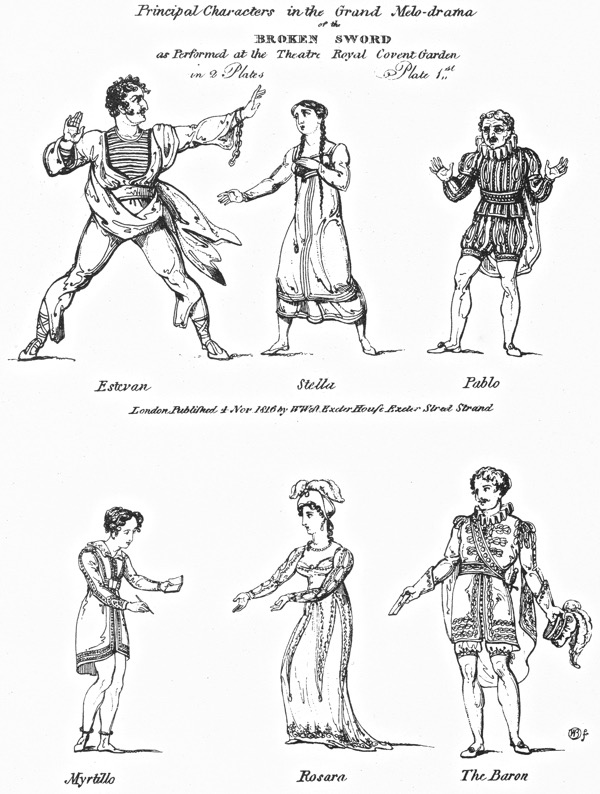

Between 1830 and 1945, at a handful of addresses within a half mile of the junction of Old St and City Rd, the modest art of publishing engraved plates of characters and scenery for Juvenile Dramas enjoyed its heyday. The names of the protagonists were William Webb and Benjamin Pollock. The overture was the opening of Archibald Park’s shop at 6 Old St Rd in 1830, and the drama was brought to the public eye by Robert Louis Stevenson in his essay A Penny Plain and Twopence Coloured in 1884, before meeting an ignominious end with the bombing of Benjamin Pollock’s shop in Hoxton St in 1945.

Responsibility for the origin of this vein of publishing belongs both to John Kilby Green of Lambeth and William West of Wych St in the Strand, with the earliest surviving sheets dated at 1811. Green was just an apprentice when he had the notion to produce sheets of theatrical characters but it was West who took the idea further, publishing plates of popular contemporary dramas. From the beginning, the engraved plates became currency in their own right and many of Green’s vast output were later acquired by Redington of Hoxton and eventually published there as Pollock’s. West is chiefly remembered for commissioning artists of acknowledged eminence to design plates, including the Cruickshank brothers, Henry Flaxman, Robert Dighton and – most notably – William Blake.

Green had briefly collaborated to open Green & Slee’s Theatrical Print Warehouse at 5 Artillery Lane, Spitalfields, in 1805 to produce ‘The Tiger’s Horde’ but the first major publishers of toy theatres in the East End were Archibald Park and his family, rising to prosperity with premises in Old St and then 47 Leonard St between 1830 until 1870.

Park’s apprentice from 1835-42, William Webb, set up on his own with shops in Cloth Fair and Bermondsey before eventually opening a quarter a mile from his master at 49 (renumbered as 146) Old St in 1857. Webb traded here until his death in 1898 when his son moved to 124 Old St where he was in business until 1931. Contrary to popular belief, it was William Webb who inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous essay upon the subject of toy theatres. Yet a disagreement between the two men led to Stevenson approaching Webb’s rival Benjamin Pollock in Hoxton St, who became the subject of the story instead and whose name became the byword for toy theatres.

In 1876, at twenty-one years old, Benjamin Pollock had the good fortune to acquire by marriage the shop opened by his late father-in-law, John Redington in Hoxton in 1851. Redington had all the theatrical plates engraved JK Green and, in time, Benjamin Pollock altered these plates, erasing the name of ‘Redington’ and replacing it with his own just as Redington had once erased the name ‘Green’ before him. Although it was an unpromising business at the end of the nineteenth century, Pollock harnessed himself to the work, demonstrating flair and aptitude by producing high quality reproductions from the old plates, removing ‘modern’ lettering applied by Redington and commissioning new designs from the naive artist James Tofts.

In 1931, the writer AE Wilson had the forethought to visit Webb’s shop in Old St and Pollock’s in Hoxton St, talking to William Webb’s son Harry and to Benjamin Pollock, the last representatives of the two surviving dynasties in the arcane world of Juvenile Dramas. “In his heyday, his business was very flourishing,” admitted Harry Webb speaking of his father,” Why, I remember we employed four families to do the colouring. There must have been at least fifteen people engaged in the work. I could tell their work apart, no two of them coloured alike. Some of the work was beautifully done.”

Harry recalled visits by Robert Louis Stevenson and Charles Dickens to his father’s premises. “Up to the time of the quarrel, Stevenson was a frequent visitor to the shop, he was very fond of my father’s plays. Indeed it was my father who supplied the shop in Edinburgh from which he bought his prints as a boy,” he told Wilson.

Benjamin Pollock was seventy-five years old when Wilson met him and ‘spoke in strains not unmingled with melancholy.’ “Toy theatres are too slow for the modern boy and girl,” he confessed to Wilson, “even my own grandchildren aren’t interested. One Christmas, I didn’t sell a single stage.” Yet Pollock spoke passionately recalling visits by Ellen Terry and Charlie Chaplin to purchase theatres. “I still get a few elderly customers,” Pollock revealed, “Only the other day, a City gentleman drove up here in a car and bought a selection of plays. He said he had collected them as a boy. Practically all the stock has been here fifty years or so. There’s enough to last out my time, I reckon.”

Shortly after AE Wilson’s visit to Old St & Hoxton, Webb’s shop was demolished while Benjamin Pollock struggled to earn even the rent for his tiny premises until his death in 1937. Harry Webb lived on in Caslon St – named after the famous letter founder who set up there two centuries earlier – opposite the site of his father’s Old St shop until his death in 1962.

Robert Louis Stevenson visited 73 Hoxton St in 1884. “If you love art, folly or the bright eyes of children speed to Pollock’s” he wrote fondly afterwards. Stevenson was an only child who played with toy theatres to amuse himself in the frequent absences from school due to sickness when he was growing up in Edinburgh. I too was an only child enchanted by the magic of toy theatres, especially at Christmas, but I cannot quite put my finger on what still draws me to the romance of them.

Even Stevenson admitted “The purchase and the first half hour at home, that was the summit.” As a child, I think the making of them was the greater part of the pleasure, cutting out the figures and glueing it all together. “I cannot deny the joy that attended the illumination, nor can I quite forget that child, who forgoing pleasure, stoops to tuppence coloured,” Stevenson concluded wryly. I cannot imagine what he would have made of Old St’s ‘Silicon Roundabout’ today.

Drawings for toy theatre characters by William Blake for William West

The sheet as published by William West, November 4th 1816 – note Blake’s initials, bottom right

Another sheet engraved after drawings by William Blake, 1814

Another sheet engraved after drawings by William Blake, 1814

124 Old St, 1931

73 Hoxton St (formerly 208 Hoxton Old Town) 1931

Benjamin Pollock at his shop on Hoxton St in 1931

Fourteenth Annual Report

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

Fourteen years ago this week I began publishing daily in these pages with the ambition of reaching at least ten thousand posts, which would take twenty-seven years and four months. It seemed an outlandish endeavour then, yet recently I passed the halfway point without even noticing until a reader wrote to congratulate me.

I was motivated by the knowledge that my parents had both died at exactly the same age and ten thousand days would deliver me to that time. So I sought a means to make my days as rewarding and productive as I could through writing and participating in the life surrounding me. I happy to admit to you that in these terms the project has succeeded beyond all expectation.

Ten years ago, the readers of Spitalfields Life campaigned to save the Marquis of Lansdowne from 1838 in Haggerston from demolition and today it is restored as part of the Museum of the Home. Five years ago, we campaigned to save the five-hundred-year-old Bethnal Green Mulberry and now it is protected. This year, the mulberry cuttings have rooted and we plan to distribute them this autumn to those patient souls who contributed £100 or more to the legal fund.

As I write, Liverpool St Station and the Bishopsgate Bathhouse are under threat from development, while the #SaveBrickLane Coalition – of which Spitalfields Life is part – prepares to go to the Supreme Court to challenge the Truman Brewery’s plans for a shopping mall.

Down in Whitechapel, the bell foundry has been rotting since its closure five years ago, acquiring layers of graffiti now that the neglect is tangible. The developers have abandoned their plan for a boutique hotel and it has been on sale without takers for a year, despite a standing offer at market value from the London Bell Foundry to buy it to start casting bells again and cherish the historic buildings.

On a brighter note, in November last year it was my great delight to speak at the party for the tenth birthday of the East End Trades Guild of which I am proud have been one of the founders. You may have read recently of the Guild’s heroic campaign to champion the rights of Len Maloney and other tenants of railway arches in the face of excessive rent increases.

Eleven years have passed since I wrote my book Spitalfields Life and ten since I became a publisher myself with The Gentle Author’s London Album in 2013. Then I published twenty titles before the pandemic called a halt to operations. But this autumn I plan relaunch Spitalfields Life Books starting with a crowdfunding campaign next month and at least four new titles in hand.

When I take a reckoning of these milestones and contemplate the future, I do not regret my choice to embrace the relentless progress of life in this corner of London.

Thus, with all these thoughts in mind, I come to the end of the fourteenth year in the pages of Spitalfields Life.

I am your loyal servant

The Gentle Author

25th August 2023

The Gentle Author’s cat, Schrodinger (formerly of Shoreditch Church)

You may like to read my earlier Annual Reports

Summer At Bow Cemetery

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

At least once each Summer, I direct my steps eastwards from Spitalfields along the Mile End Rd towards Bow Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” created by act of Parliament in 1832 as the growing population of London overcrowded the small parish churchyards. Extending to twenty-seven acres and planned on an industrial scale, “The City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery” as it was formally called, opened in 1841 and within the first half century alone around a quarter of a million were buried here.

Although it is the tombstones and monuments that present a striking display today, most of the occupants of this cemetery were residents of the East End whose families could not afford a funeral or a plot. They were buried in mass public graves containing as many as forty bodies of random souls interred together for eternity. By the end of the nineteenth century the site was already overgrown, though burials continued until it was closed in 1966.

Where death once held dominion, nature has reclaimed the territory and a magnificent broadleaf forest has grown, bringing luxuriant growth that is alive with wildlife. Now the tombstones and monuments stand among leaf mould in deep woods, garlanded with ivy and surrounded by wildflowers. Tombstones and undergrowth make one of the most lyrical contrasts I can think of – there is a beautiful aesthetic manifest in the grim austerity of the stones ameliorated by vigorous plant life. But more than this, to see the symbols of death physically overwhelmed by extravagant new growth touches the human spirit. It is both humbling and uplifting at the same time. It is the triumph of life. Nature has returned and brought more than sixteen species of butterflies with her.

This is the emotive spectacle that leads me here, turning right at Mile End tube station and hurrying down Southern Grove, increasing my pace with rising expectation, until I walk through the cemetery gates and I am transported into the green world that awaits. At once, I turn right into Sanctuary Wood, stepping off the track to walk into a tall stand of ivy-clad sycamores, upon a carpet of leaves that is shaded by the forest canopy more than twenty metres overhead and illuminated by narrow shafts of sunlight descending. It is sublime. Come here to see the bluebells in Spring or the foxgloves in Summer. Come at any time of the year to find yourself in another landscape. Just like the forest in Richard Jefferies’ novel “After London,” the trees have regrown to remind us what this land was once like, long ago before our predecessors ever came here.

Over time, the tombstones have weathered and worn, and some have turned green, entirely harmonious with their overgrown environment, as if they sprouted and grew like toadstools. The natural stillness of the forest possesses greater resonance between cemetery walls and the deep green shadows of the woodland seem deeper too. There was almost no-one alive to be seen on the morning of my visit, apart from two police officers on horseback passing through, keeping the peace that is as deep as the grave.

Just as time mediates grief and grants us perspective, nature also encompasses the dead, enfolding them all, as it has done here in a green forest. These are the people who made East London, who laid the roads, built the houses and created the foundations of the city we inhabit. The countless thousands who were here before us, walking the streets we know, attending the same schools, even living in some of the same houses we live in today. The majority of those people are here now in Bow Cemetery. As you walk around, names catch your eye, Cornelius aged just two years, or Eliza or Louise or Emma, or Caleb who enjoyed a happy life, all over a hundred years ago. None ever dreamed a forest would grow over their head, where people would come to walk one day to discover their stones in a woodland glade. It is a vision of paradise above, fulfilled within the confines of the cemetery itself.

As I made my progress through the forest of tombstones, I heard a mysterious noise, a click-clack echoing through the trees. Then I came upon a clearing at the very heart of the cemetery and discovered the origin of the sound. It was a solitary juggler practicing his art among the graves, in a patch of sunlight. There is no purpose to juggling than that of delight, the attunement of human reflexes to create a joyful effect. It was a startling image to discover, and seeing it here in the deep woods – where so many fellow Londoners are buried – made my heart leap. In the vast wooded cemetery there was just me, the numberless dead and the juggler.

You may also like to read about

At Canvey Island

Click here to book for my tours through September and October

Inspired by a brochure given to me by Gary Arber, I decided to go for a day trip to Canvey Island. Printed by W.F.Arber & Co Ltd in the Roman Rd in the nineteen twenties – when Gary’s grandfather Walter ran the shop, his father (also Walter) was the compositor and uncles Len and Albert ran the presses – this brochure seduced me with its lyrical prose.

“Canvey Island, owing to its unique position at the meeting place of fresh and salt waters, which continually wash its shores, enjoys a nascent air which is extraordinarily health-giving and invigorating, and is, indeed in this respect, possibly above all other places in the kingdom. Prominent physicians in our leading hospitals pay tribute to the properties of the air, by sending patients to the Island in preference to any other locality.”

Yet in spite of this irresistible account of the Island’s charms, when I told people I was going to Canvey, they pulled long faces and declared, “You’re joking?” Undeterred by prejudice, I packed ham sandwiches in my satchel and set out from Fenchurch St Station with an open mind to discover Canvey Island for myself. Alighting at Benfleet, I crossed the River Ray to the Island arriving at the famous wall that reclaimed the land from the sea – constructed in the seventeenth century by three hundred dutch dyke diggers under the supervision of Cornelius Vermuyden.

“One of the first places the visitor will make for is the sea-wall, which he has undoubtedly heard a good deal about before coming to Canvey, and with which he will be anxious to make a closer acquaintance. The wall completely encircles the Island, and, following all its windings in and out, covers a distance of about eighteen miles.”

Since I had no map and had not been to Canvey before, Gary Arber’s brochure was my only guide. And so I set out along the wall where stonecrop and asters grew wild, buffered and blown by salt winds from the estuary. With a golf course to the landward side and salt marshes to the seaward side, that widened out into a vast open expanse stretching away towards Southend Pier on the horizon, it was an exhilarating prospect and I enjoyed the opportunity to fill my lungs with fresh sea air.

“The grand secret of the wonderful health-giving properties of the air is the evaporation from the “saltings,” during the time when the tides are out, which charges the air with ozone, which is thus constantly renewed and refreshed, making it extremely healthy, clean and bracing.”

Reaching Canvey Heights and looking back, the contrast between the hinterland crowded with bungalows and whimsical cottages, and the bare salt flats beyond the wall became vividly apparent. Many thousands before me, coming to escape from East London, had also been captivated by the Island romance that Canvey weaves – and I could understand their affection for this charmed Isle that proposes such a persuasive pastoral idyll, when resplendent beneath a sky of luminous blue.

“There is a charming freedom about life on Canvey which will appeal to most people whose work-a-day life has to be spent in towns or their suburbs. The change of scene is complete in every respect; streets, bricks and mortar, are replaced by bungalows of very varied designs and appearances”

Surrounding Canvey Heights, I found a neglected orchard of different varieties of plum trees all heavy with fruit, and filled my satchel with a selection of red, yellow and purple plums, before making my way to Rapkins Wharf with its magnificent old hulks nestled together in a forgotten creek. The Island breezes played upon the rigging like a wind harp, filling the boat yard with other-worldly music, where old sea salts sheltering amongst the array of rotting vessels. Next, turning the corner of the Island, I reached the shore facing the estuary and walking along the esplanade soon came to Concord Beach Paddling Pool where I joined the happy throng at the tea stall, spying the big ships that pass close by.

“All the vessels, bound to and from the large ports on the Thames, must pass Canvey, and thus a constant procession of all sizes can be watched with interest and pleasure, ploughing their lonely furrows through the waters. Monster ocean-going liners bound for the other side of the world, sailing vessels with their full rig of canvas spread, and, as the sun catches the sails, delighting the eye with one of the most haunting sights to be imagined – the estuary teems with interest at all times. Here one can realise that, despite the progress of motor and steam in water travel, there still remain a few ocean-going vessels under sail only.”

At the next table, a group of residents were debating the relative merits of Benidorm and Costa del Sol as holiday destinations, only to arrive at the startling yet prudent consensus that staying here in Canvey Island was best. Eavesdropping on their conversation, and observing the idiosyncratic villas adorned with pigeon lofts and flags, I recognised that an atmosphere of gleeful Island anarchy reigns in Canvey, situated at one remove from mainland Britain.

“The strict conventions of dress and deportment so tiresomely observed in towns can be ignored here in Canvey, and the visitor casts off all artificial restraints, simply observing the ordinary rules of decency and respect towards others which his own courtesy will dictate.”

Crossing through the streets, marvelling at the varieties of bungalows, I came to the Canvey Island Rugby Club playing field at Tewkes Creek, where I sat upon a bench to rest and admire the egrets feeding in the creek, while men walked their bull terriers on the green. Tracing my path back along the wall towards Benfleet station, I discovered circles of field mushrooms and picked myself a bunch of the wild fennel that grows in abundance, imparting its fragrance to the breeze. Then I returned home on the train to Fenchurch St at six, pleasantly weary, sunburnt and windswept, with my mushrooms, plums and fennel in hand as trophies, enraptured by all the delights of Canvey.

“For the family there is no better spot than Canvey for holidays – the glorious, exhilarating air sends them home again pictures of health and happiness.”

I never saw Canvey Island’s petrochemical refineries, or what happens at night. I am prepared to countenance that Canvey has its dark side, but I was innocent of it. I am an unashamed day-tripper.

This boat is for sale, contact the owner at Rapkins Wharf, Canvey Island.

Mushrooms picked at Canvey

Plums and fennel from Canvey

The wall around Canvey Island

At Walton On The Naze

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

All this time, Walton on the Naze has been awaiting me, nestling like a forgotten jewel cast up on the Essex coast, and less than an hour and a half from Liverpool St Station.

Families with buckets and spades joined the train at every stop, as we made our way eastwards to the point where Essex crumbles into the North Sea at the rate of two metres a year. Yet all this erosion, while reminding us of the force of the mighty elements, also delivers a perfect sandy beach – the colour of Cheddar cheese – that is ideal for sand castles and digging. Stepping from the small train amongst the flurry of pushchairs and picnic bags, at once the sea air transports you and the hazy resort atmosphere enfolds you. Unable to contain yourself, you hurry through the sparse streets of peeling nineteenth century villas and shabby weather-boarded cottages to arrive at a rise overlooking Britain’s third longest pier, begun in 1830.

In spite of the majestic pier, this is a seaside resort on a domestic scale. You will not find any foreign tourists here because Walton on the Naze is a closely guarded secret, it is kept by the good people of Essex for their sole use. At Walton on the Naze everyone is local. You see Essex families running around as if they owned the place, playing upon the beach in flagrant carefree abandon, as if it were their own back yard – which, in a sense, it is.

This sense of ownership is manifest in the culture of the beach huts that line the seafront, layers deep, in higgledy-piggledy terraces receding from the shore. These little wooden sheds are ideal for everyone to indulge their play house and dolls’ house fantasies – painting them in fanciful colours, giving them names like “Ava Rest,” and furnishing the interiors with gas cookers and garish curtains. At the seaside, all are licenced to pursue the fulfilment of residual childhood yearning in harmless whimsy. The seaside offers a place charged with potent emotional memory that we can return to each Summer. It is not simply that people get nostalgic for seaside resorts, but that these seasonal towns become the location of nostalgia itself – because the sea never changes and we revisit our former selves when we come back to the beach.

Walton Pier curls to one side like a great tongue taking a greedy lick from an ocean of ice cream, and the beach curves away in a crooked smile that leads your eye to the “Naze,” or “nose” to give its modern spelling. This vast bulbous proboscis extends from the profile of Essex as if from a patient in need of plastic surgery, provided in the form of relentless abrasion from the sea.

With so many attractions, the first thing to do is to sit down at the tables upon the beach outside Sunray’s Kiosk which serves the best fish & chips in Walton on the Naze. Every single order is battered and cooked separately in this tiny establishment, that also sells paper flags for sandcastles and shrimping nets and all essential beach paraphernalia. From here a path leads past a long parade of beach huts permitting you the opportunity to spy upon these domestic theatres, each with their proud owners lounging outside while their children run back and forth, vacillating between their haven of security and the irresistible wonder of the waves crashing at the shoreline.

Here I joined some girls, excitedly fishing for crabs with hooks and lines off a small jetty. They all screamed when one pulled out a much larger specimen than the tiddlers they had in their buckets, only to be reassured by the woman who was overseeing their endeavour. “Don’t be frightened – it’s just the Mummy!” she declared with a wicked smile, as she held up the struggling creature by a claw. From this jetty, I could see the eighty foot tower built upon the Naze in 1720 as a marker for ships entering the port of Harwich and after a gentle climb up a cliff path, and a strenuous ascent up a spiral staircase, I reached the top. Like a fly perched upon the nose of Essex, I could look North across the estuary of the Orwell towards Suffolk on the far shore and South to the Thames estuary with Kent beyond – while inland I could see the maze of inlets, appealingly known as the Twizzle.

I was blessed with a clear day of sunshine for my holiday. And I returned to the narrow streets of Spitalfields for another year with my skin flushed and buffeted by the elements – grateful to have experienced again the thrall of the shoreline, where the land runs out and the great ocean begins.

Sunray’s Kiosk on the beach, for the best fish & chips in Walton on the Naze.

“On this promontory is a new sea mark, erected by the Trinity-House men, and at the publick expence, being a round brick tower, near eighty foot high. The sea gains so much upon the land here, by the continual winds at S.W. that within the memory of some of the inhabitants there, they have lost above thirty acres of land in one place.” Daniel Defoe, 1722

My Pub Crawl From Smithfield To Holborn

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

What could be a nicer way to spend a lazy late summer afternoon than slouching around the pubs of Smithfield, Newgate, Holborn and Bloomsbury?

The Hand & Shears, Middle St, Clothfair, Smithfield

The Hand & Shears – They claim that the term ‘On The Wagon’ originated here – this pub was used for a last drink when condemned men were brought on a wagon on their way to Newgate Prison to be hanged – if the landlord asked ,“Do you want another?” the reply was “No, I’m on the wagon” as the rule was one drink only.

The Rising Sun – reputedly the haunt of body-snatchers selling cadavers to St Bart’s Hospital

The Rising Sun and St Bartholomew, Smithfield.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate St– the last surviving example of a Victorian Gin Palace, it is notorious for poltergeist activity apparently.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

Princess Louise, High Holborn – interior of 1891 by Arthur Chitty with tiles by W. B. Simpson & Sons and glass by R. Morris & Son

Window at the Princess Louise, Holborn

Princess Louise

Princess Louise

Cittie of Yorke, High Holborn

The Lamb, Lamb’s Conduit St, Bloomsbury – built in the seventeen-twenties and named after William Lamb who erected a water conduit in the street in 1577. Charles Dickens visited, and Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath came here.

The Lamb

The Lamb

You may also like to look at