Vagabondiana

We are doing some work to repair www.spitalfieldslife.com and improve its stability and functioning. From Wednesday, the site may not always be accessible and the mailings will not go out on Thursday and Friday. By the weekend we will back, better than ever. We thank our readers for your patience.

This is William Conway of Crab Tree Row, Bethnal Green, who walked twenty-five miles every day, calling, “Hard metal spoons to sell or change.” Born in 1752 in Worship St, Spitalfields, he is pictured here forty-seven years into his profession, following in the footsteps of his father, also an itinerant trader. Conway had eleven walks around London which he took in turn, wore out a pair of boots every six weeks and claimed that he never knew a day’s illness.

This is just one of the remarkable portraits by John Thomas Smith collected together in a large handsome volume entitled “Vagabondiana,” published in 1817, that it was my delight to discover in the collection of the Bishopsgate Institute. John Thomas Smith is an intriguing and unjustly neglected artist of the early nineteenth century who is chiefly remembered today for being born in the back of a Hackney carriage in Great Portland St and for his murky portrait of Joseph Mallord William Turner.

On the opening page of “Vagabondiana”, Smith’s project is introduced to the reader with delicately ambiguous irony. “Beggary, of late, has become so dreadful in London, that the more active interference of the legislature was deemed absolutely necessary, indeed the deceptions of the idle and sturdy were so various, cunning and extensive, that it was in most instances extremely difficult to discover the real object of charity. Concluding, therefore, that from the reduction of metropolitan beggars, several curious characters would disappear by being either compelled to industry, or to partake of the liberal parochial rates, provided for them in their respective work-houses, it occurred to the author of the present publication, that likenesses of the most remarkable of them, with a few particulars of their habits, would not be unamusing to those to whom they have been a pest for several years.”

Yet in spite of these apparently self-righteous, Scrooge-like, sentiments – that today might be still be voiced by any number of venerable bigots – John Thomas Smith’s pictures tell another story. From the moment I cast my eyes upon these breathtakingly beautiful engravings, I was captivated by their human presence. There are few smiling faces here, because Smith allows his subjects to retain their self possession, and his fine calligraphic line celebrates their idiosyncrasy borne of ingenious strategies to survive on the street.

You can tell from these works that John Thomas Smith loved Rembrandt, Hogarth and Goya’s prints because the stylistic influences are clear, in fact Smith became keeper of drawings and prints at the British Museum. More surprising is how modern these drawings feel – there are several that could pass as the work of Mervyn Peake. Heath Robinson’s drawings also spring to mind, especially his illustrations to Shakespeare and there are a couple of craggy stooping figures woven of jagged lines that are worthy of Ronald Searle or Quentin Blake.

If you are looking for the poetry of life, you will find it in abundance in these unsentimental yet compassionate studies that cut across two centuries to bring us a vivid sense of London street life in 1817. It is a dazzling vision of London that Smith proposes, populated by his vibrant characters.

The quality of Smith’s portraits transcend any condescension because through his sympathetic curiosity Smith came to portray his vagabonds with dignity, befitting an artist who was literally born in the street, who walked the city, who knew these people and who drew them in the street. He narrowly escaped a lynch mob once when his motives were misconstrued and he was mistaken for a police sketch artist. No wonder his biography states that,“Mr Smith happily escaped the necessity of continuing his labours as an artist, being appointed keeper of prints & drawings at the British Museum.”

Smith described his subjects as “curious characters” and while some may be exotic, it is obvious that these people cannot all fairly be classed as vagabonds, unless we chose instead to celebrate “Vagabondiana” as the self-respecting state of those who eek existence at the margins through their own wits. One cannot deny the romance of vagabond life, with its own culture and custom. Through pathos, John Thomas Smith sought to expose common human qualities and show vagabonds as people, rather than merely as pests or vermin to be driven out.

A Jewish mendicant, unable to walk, who sat in a box on wheels in Petticoat Lane.

Israel Potter, one of the oldest menders of chairs still living.

Strolling clowns

Bernado Millano, the bladder man

Itinerant third generation vendor of elegies, Christmas carols and love songs

A crippled sailor advertises his maritime past

George Smith, a brush maker afflicted with rheumatism who sold chickweed as bird food.

A native of Lucca accompanying his dancing dolls upon the bagpipes

Blinded in one eye, this beggar seeks reward for sweeping the street

Priscilla who sat in the street in Clerkenwell making quilts

Anatony Antonini, selling artificial silk flowers adorned with birds cast in wax

This boot lace seller was a Scotman who lost his hands in the wars

Charles Wood and his dancing dog.

Staffordshire ware vendors bought their stock from the Paddington basin and sold it door to door.

Rattle-puzzle vendors.

A blind beggar with a note hung round his neck appealing for charity.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Matchbox Models By Lesney

It is my pleasure to publish the Matchbox 1966 Collector’s Guide & International Catalogue by Lesney Products & Co Ltd of Hackney Wick, courtesy of the late Libby Hall. The company was founded by Leslie & Rodney Smith in 1947 , closed in 1982 and the Lesney factory was demolished in 2010.

It all began in 1953, with a miniature diecast model of the Coronation Coach with its team of eight horses. In Coronation year, over a million were sold and this tremendous success was followed by the introduction of the first miniature vehicle models packed in matchboxes. And so the famous Matchbox Series was born.

More than five hundred million Matchbox models have been made since the series was first introduced during 1953, and today over two million Matchbox models are made every week. The life of a new model begins at a design meeting attended by Lesney senior executives. The suitability of a particular vehicle as a Matchbox model is discussed and the manufacturer of the full-sized car is approached for photographs, drawings and other information. Enthusiastic support is received from manufacturers throughout the world and many top secret, exciting new cars are on the Matchbox drawings boards long before they are launched to the world markets.

1. Once the details of the full-size vehicle have been obtained, many hours of careful work are required in the main drawing office in Hackney.

2. In the pattern shop, highly specialised craftsmen carve large wooden models which form the basic shape from which the miniature will eventually be diecast in millions.

3. Over a hundred skilled toolmakers are employed making the moulds for Matchbox models from the finest grade of chrome-vinadium steel.

4. There are more than one hundred and fifty automatic diecasting machines at Hackney and all have been designed, built and installed by Lesney engineers.

5. The spray shop uses nearly two thousand gallons of lead-free paint every week, and over two and a half million parts can be stove-enamelled every day.

6. Final assembly takes place over twenty lines, and sometimes several different models and their components come down each line at the same time.

7. Ingenious packing machines pick up the flat boxes, shape them and seal the model at the rate of more than one hundred and twenty items per minute.

8. Ultra-modern, automatic handling and automatic conveyor systems speed the finished models to the transit stores where electronic selection equipment routes each package.

From the highly individual, skilled worker or the enthusiast who produces hand-made samples of new ideas, to the multi-million mass assembly of the finished models by hundreds of workers, this is the remarkable story of Matchbox models. Over three thousand six hundred people play their part in a great team with the highest score in the world – over a hundred million models made and sold per year. Enthusiasts of all ages throughout the world collect and enjoy Matchbox models today and it is a true but amazing fact that if all the models from a year’s work in the Lesney factories were placed nose to tail they would stretch from London to Mexico City – a distance of over six thousand miles!

You may also like to take a look at these other magnificent catalogues

Philip Cunningham’s Portraits

In the seventies, while living in Mile End Place and employed as a Youth Worker at Oxford House in Bethnal Green and then as a Probationary Teacher at Brooke House School in Clapton, Photographer Philip Cunningham took these tender portraits of his friends and colleagues. “I love the East End and often dream of it,” Philip admitted to me recently.

Publican at The Albion, Bethnal Green Rd. “We would often go there from Oxford House where I was a youth worker. Billy Quinn, ‘The Hungry Fighter’ used to drink in there. He would shuffle in, in his slippers and, if I offered him a drink, the answer was always the same. ‘No! No! I don’t want a drink off you, I saved my money!’ He had fought a lot of bouts in America and was a great character.”

Proprietor of Barratts’ hardware – “An unbelievable shop in Stepney Way. It sold EVERYTHING, including paraffin – a shop you would not see nowadays.”

Terry & Brenda Green, publicans at The Three Crowns, Mile End

“My drinking pal, Grahame the window cleaner, knew all that was happening on the Mile End Rd.”

Oxford House bar

“Bob Drinkwater ran the youth club at Oxford House where I was a youth worker” c. 1974

Pat Leeder worked as a volunteer at Oxford House

Caretaker at Oxford House

My friend Michael Chalkley worked for the Bangladeshi Youth League and Bangladeshi Welfare Association

Frank Sewell worked at Kingsley Hall, Bow, and ran a second hand shop of which the proceeds went to the Hall, which was ruinous at that time

Historian Bill Fishman in Whitechapel Market

Mr Green

Kids from the youth club at Oxford House, Weavers’ Fields Adventure Playground, c. 1974

Kids from the youth club at Oxford House, Weavers’ Fields Adventure Playground, c. 1974

Salim, Noorjahan, Jabid and Sobir with Michael Chalkley, c. 1977

Coal Men, A G Martin & Sons, delivering to Mile End Place

Mr & Mrs Jacobs, neighbours at Mile End Place

Mr & Mrs Mills, neighbours at Mile End Place

Commie Roofers, Mile End Place

Friend and fighter against racism, Sunwah Ali at the Bangladeshi Youth League office, c. 1978

Norr Miah was a friend, colleague and trustee of the Bangladeshi Youth League

Chess players at Brooke House School, c. 1979

Teacher at Brooke House – “The best school I ever taught in with a really congenial staff” c. 1979

“Boys from Brooke House School where I was a probationary teacher, c.1979”

“My friend and colleague Salim Ullah with his baby” c.1977

John Smeeth (AKA John the Beard), my daughter Andrea, and Michael Wiston (AKA Whizzy) c. 1977

Eddie Marsan (dressed as Superman) and friends, Mile End Place

“Rembert Langham in our studio in New Crane Wharf, Wapping. He made monsters for Dr Who and went pot-holing”1975

“John the Fruit used to drink in the Three Crowns and we were good friends. We were in the pub one night when some tough characters came in. It turned out they owned this property I had been photographing. I asked if I could do some photos inside, they said, ‘Yes, come on Thursday.’ I duly arrived, but the place was locked and no one was about. Then John the Fruit turned up so I took his picture, as you see above. Later that week in the Three Crowns, the rough guys walked in and, when they saw me, accused me of not turning up. I was grabbed by the shoulder to be taken outside (very nasty). However John, who was an ex-boxer and pretty fit for an old boy, pulled the bloke holding me aside and said ‘He was there, because I was there with him!’ They put me down and were most apologetic to John. He saved me from something bad, God Bless Him!!”

Abdul Bari & friend, Whitechapel. “Abdul Bari (Botly Boy) lived in the Bancroft Estate and was a parent at John Scurr School where I was a governor and where my daughter attended. The photo was taken on Christmas day.”

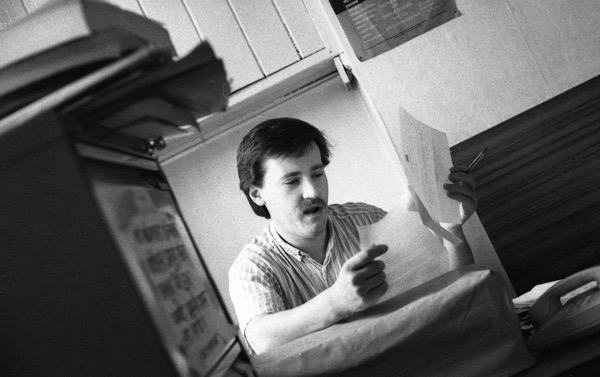

Printer at the Surma newspaper, Brick Lane. The paper supported Sheikh Mujibur Rahman & the Awami League.

Porters at Spitalfields Market c.1978

Porters at Spitalfields Market c.1978

Boys on wasteland, Whitechapel c.1977

My friends Sadie & Murat Ozturk ran the kebab shop on Mile End Rd. Their daughter Aysher was best friends with my daughter and both went to John Scurr School. We spent alternate Christmases at each others’ home until they returned to Turkey. They were very hard-working and I hope they have prospered. c.1978

Engineers in the Mile End Automatic Laundry. It was a fantastic facility for people like us, with just an outside toilet and a butler’s sink in the kitchen. It had machines to iron your sheets which was a palaver, but everyone used to help each another. c.1975

Jan Alam & Union Steward, Raj Jalal on an Anti-Fascist march in Whitechapel

Chris Carpenter & Jim Wolveridge on Mile End Waste. My long-time friend Chris was a teacher at John Scurr School who went to Zimbabwe to teach for a number of years. When he arrived there were very few books in the School, but oddly there was one called ‘Ain’t It Grand’ by Jim Wolveridge. How it got there nobody could explain. Jim Wolveridge used to have a second hand book stall on the Waste every Saturday. In this photo, Chris is telling him about finding his book in his school in Zimbabwe. c.1985

My photography student Rodney at Deptford Green Youth Centre would often say ‘Hush up & listen to the Teach!’

Michael Rosen and Nik Chakraborty both taught my daughter at John Scurr School. c.1979

Photography students at Deptford Green Youth Centre. They were eager to learn and I hope they’ve all done well. c.1979

My friend and colleague, Caroline Merion at Tower Hamlets Local History Library where she spent most of her time. I went to her house once or twice and I noticed she had a habit of hoarding bags. c.1979

Harry Watton worked in the Local History Library in Bancroft Rd for many years. He was always helpful and had an immense knowledge about Tower Hamlets. c.1979

The Rev David Moore from the Bow Mission and Santiago Bell, an exile from Pinochet’s Chile who was a ceramicist and wood carver. He taught David to carve and, on retirement, David built himself a studio and has been carving ever since. This picture was taken at the opening of Bow Single Homeless & Alcoholic Rehabilitation Project and the carving, which was the work of both David and Santiago, depicts the journey of rehabilitation. c.1986

Builders at Oxford House. c.1978

Gasmen at Mile End Place, 1977

Harry Diamond at a beer festival at Stepping Stones Farm Stepney. After I left art school in 1978, I met Harry at Camerawork in Alie St. He was always generous with his knowledge of photography and, after talking to him, I changed the type of film I was using. Harry was famously painted by Lucien Freud standing next to a pot plant, but when I asked Harry what he thought of Lucien, he did not have a high opinion of the great artist. c.1978

Teacher Martin Cale and Bob the School-keeper (an ex-docker) at John Scurr School. c.1978

At Hungerford Bridge, I came across this man in a doorway. He was not yet asleep so I asked if I could take his photo. ‘If you give me a cigarette,’ he said. ‘I only smoke rollups,’ I replied. ‘That’ll do.’ I rolled him a cigarette then took his portrait. c.1978

Paul Rutishauser ran the print workshop in the basement of St George’s Town Hall in Cable St

‘We don’t want to live in Southend’ – Housing demonstration on the steps of the old Town Hall

Kids from Stepping Stones Farm in Stepney c.1980

“Kingsley Hall was a Charles Voysey designed building off Devons Rd, Bow, that had fallen into disrepair and which we were trying to turn into a community centre.”

Kids from Kingsley Hall

In the pub with Geoff Cade and Helen Jefferies (centre and right) who worked at Kingsley Hall

“Geoffrey Cade worked at Kingsley Hall from about 1982. He fought injustice all his life and was a founding member of Campaign for Police Accountability, a good friend and colleague.”

East London Advertiser reporters strike in Bethnal Green, long before the paper moved to Romford c.1979

National Association of Local Government Officers on strike at the Ocean Estate

Teachers on strike c. 1984

Policing the Teacher’s Strike c. 1984

Teachers of George Green’s School, Isle of Dogs, in support of Ambulance Crews c. 1983

Kevin Courtney was my National Union of Teachers Representative when I began my teaching career

Lollipop Lady in Devons Rd, Bow

“Our first play scheme was in the summer of 1979. One of the workers was a musician called Lesley and her boyfriend was forming a band, so they asked me to photograph them and, as they lived on the Ocean Estate, we went into Mile End Park to do the shoot.”

Does anyone remember the name of this band?

Busker in Cheshire St c. 1979

“We bought our fruit and vegetables every Saturday from John the greengrocer in Globe Rd who did all his business in old money.” c.1980

Photographs copyright © Philip Cunningham

You may also like to take a look at

The Silent Traveller

When I encountered the work of Chiang Yee (1903-77) writing as ‘The Silent Traveller’ I knew I had discovered a kindred spirit in self-effacement. These fine illustrations are from his book ‘The Silent Traveller in London’ published in 1938 and I am fascinated by his distinctive vision which renders familiar subjects anew.

‘This book is to be a sort of record of all the things I have talked over to myself during these five years in London, where I have been so silent,’ he wrote, ‘I am bound to look at things from a different angle, but I have never agreed with people who hold that the various nationalities differ greatly from each other. They may be different superficially, but they eat, drink, sleep, dress, and shelter themselves from the wind and rain in the same way.’

Summer afternoon in Kew Gardens

Morning mist in St James’s Park

Snow on Hampstead Heath

Early Autumn in Kenwood

Fog in Trafalgar Sq

Coalman in the rain

Umbrellas Under Big Ben

Deer in Richmond Park

Seagulls in Regent’s Park

At the Whitechapel Gallery

London faces in a public bar

London faces in winter

Coronation night in the Underground

Jubilee night in Trafalgar Sq

London faces at a Punch & Judy show

Images copyright © Estate of Chiang Yee

You may also like to take a look at

The Kiosks Of Whitechapel

Mr Roni in Vallance Rd

As the east wind whistles down the Whitechapel Rd spare a thought for the men in their kiosks, perhaps not quite as numb as the stallholders shivering out in the street but cold enough thank you very much. Yet in spite of the sub-zero temperatures, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I discovered a warm welcome when we spent an afternoon making the acquaintance of these brave souls, open for business in all weathers.

I have always marvelled at these pocket-sized emporia, intricate retail palaces in miniature which are seen to best effect at dusk, crammed with confections and novelties, all gleaming with colour and delight as the darkness enfolds them. It takes a certain strength of character as well as a hardiness in the face of the elements to present yourself in this way, your personality as your shopfront. In the manner of anchorites, bricked up in the wall yet with a window on the street and also taking a cue from fairground callers, eager to catch the attention of passersby, the kiosk men embrace the restrictions of their habitation by projecting their presence as a means to draw customers like moths to the light.

In Whitechapel, the kiosks are of two types, those offering snack food and others selling mobile phone accessories, although we did find one in Court St which sold both sweets and small electrical goods. For £1.50, Jokman Hussain will sell you a delicious hot samosa chaat and for £1 you can follow this with jelabi, produced in elaborate calligraphic curls before your eyes by Jahangir Kabir at the next kiosk. Then, if you have space left over, Mannan Molla is frying pakora in the window and selling it in paper bags through the hatch, fifty yards down the Whitechapel Rd.

Meanwhile if you have lost your charger, need batteries or a memory stick in a hurry, Mohammed Aslem and Raj Ahmed can help you out, while Mr Huld can sell you an international calling card and a strip of sachets of chutney, both essential commodities for those on-the-go.

Perhaps the most fascinating kiosks are those selling betel or paan, where customers gather in clusters enjoying the air of conspiracy and watching in fascination as the proprietor composes an elaborate mix of spices and other exotic ingredients upon a betel leaf, before folding it in precise custom and then wrapping the confection into a neat little parcel of newspaper for consumption later.

Once we had visited all the kiosks, I had consumed one samosa chaat, a jalebi, a packet of gummy worms and a bag of fresh pakora while Sarah had acquired a useful selection of batteries, a strip of chutney sachets and a new memory stick. We chewed betel, our mouths turning red as we set off from Whitechapel through the gathering dusk, delighted with our thrifty purchases and the encounters of the afternoon.

Jokman Hussain sells Samosa Chaat

Mohammed Aslem sells phone accessories and small electrical goods

Jahangir Kabir sells Jalebi

Raj Ahmed

Mannan Molla sell Pakora

Mr Duld sells sweets and phone accessories in Court St

Mr Peash

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

William Anthony, The Last Of The Charlies

William Anthony 1789-1863

Behold the face of history! Photographed in 1863, the year of his death, but born in 1789, the year of the French Revolution, seventy-four-year-old William Anthony trudged the streets of Spitalfields and Norton Folgate through the darkest nights and thickest fogs for half a century, with his nose pointed into the wind and his jaw set in determination, successfully guided by a terrier-like instinct to seek out miscreants and prevent the outbreak of any unholy excesses of violence, such as erupted on the other side of the channel at the time of his nascence.

No wonder the Watch Book of Norton Folgate recorded an unbroken sequence of “All’s Well” for his entire tenure. No robbery was reported in fifty years. There was no nonsense with William Anthony. We need him at night on Brick Lane today.

The origin of the term ‘Charley’ for Watchman may originate in the time of Charles I when the monarch improved the watch system, although Jonathon Green, Spitalfields Life Contributing Lexicographer of Slang, who informed me of this possible derivation, can find no subsequent use in print for another one hundred and fifty years, when the term achieved currency in the early nineteenth century.

‘Charley’ as a derogatory term for a foolish person has survived into modern times, yet – as these photographs attest – William Anthony was unapologetic, quite content to be a ‘Charley.’ Behind him stand a long line of ‘Charlies’ stretching back through time for as long as London has existed and I think we may discern a certain dogged pride in William Anthony’s bearing, clutching his dark lantern in one hand and knobbly staff of office in the other, swaddled up in a great coat against the cold, wrapped in an apron against the filth, shod in sturdy boots against the damp and sheltered under his stout hat from the downpour.

Now I know his appearance, I will look out for William Anthony, lest our paths cross in the wintry dusk in Blossom St or Elder St – others might disregard him as another homeless old man walking all night but I shall hail him and pay my respects to the last of the ‘Charlies.’ He is the one of whom you could truly say you would be glad to meet him in a dark alley at night.

In Norton Folgate, the Watchman recorded an unbroken sequence of “All’s Well”

Tom & Jerry “getting the best of a Charley” at Temple Bar engraved by George Cruickshank, 1832

“Past one o’clock and a fine morning!” from Thomas Rowlandson’s ‘Lower Orders’

The Watchman, 1819 from ‘Pictures of Real Life for Children’

“Past Twelve O’Clock and A Cloudy Morning! & Patrol! Patrol!” from ‘Sam Syntax’s Cries of London’

“Past twelve o’clock and a misty morning! Past twelve o’clock and mind I give you warning!” published by Charles Hindley, Leadenhall Press, 1884

“Past twelve o’clock and a misty morning! Past twelve o’clock and mind I give you warning!” published by Charles Hindley, Leadenhall Press, 1884

Watchman by John Thomas Smith, copied from a print prefixed to ‘Villanies discovered by Lanthorne and Candlelight’ by Thomas Dekker 1616. “The marching Watch contained in number two thousand men, part of them being old souldiers, of skill to be captaines, lieutenants, serjeants, corporals &c. The poore men taking wages, besides that every one had a strawne hat, with no badge painted, and his breakfast in the morning.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Dragan Novaković’s Brick Lane

These Brick Lane photographs from the late seventies by Dragan Novaković. Dragan came to London from Belgrade in 1968 and returned home in 1977, working for the state news agency Tanjug and then Reuters before his retirement in 2011.

‘I printed very rarely and very little, and for the next forty-odd years had these photographs only as contact sheets.’ explains Dragan, ‘I saw them properly as ‘enlargements’ for the first time in 2012, after I had scanned the negatives and post-processed the files.’

“I was introduced to London’s street markets by my friend and fellow countryman Mario who had a stall in Portobello Market specializing in post office clocks and bric-a-brac. I enjoyed sitting there with him amid the hustle and bustle, with people stopping by for a chat or to strike a bargain.

One early winter morning Mario picked me up in his old mini van and told me we were going to Bermondsey Market in search of clocks. It was still dark and foggy when we arrived and what met my eye made me gaze around in wonder – the scene looked to me as something out of Dickens!

The second time we went looking for clocks Mario took me to Brick Lane. Though there were plenty of open-air markets where I came from, I had seen nothing of the kind and size of Brick Lane and was fascinated by the crowds, the street musicians, the wares, the whole atmosphere. I sensed a strong community spirit and togetherness. I was hooked and I knew that I would have to come again in my spare time and take pictures.

Over the years I visited Brick Lane and other East End markets whenever I could spare the time and afford a few rolls of film. Living first in Earl’s Court and then behind Olympia, I would mount my old bicycle, bought in Brick Lane (of course!), and pedal hard across the West End in order to be there where life overflowed with activity.

I took what I consider snapshots without any plan or project in mind but simply because the challenge was too strong and I could not help it. I developed the films and made contact prints regularly but, never having a proper darkroom, made no enlargements to help me evaluate properly what I had done. Now I wish I had taken many more pictures at these locations.” – Dragan Novaković

Photographs copyright © Dragan Novaković

You also might like to take a look at