The Trade Of The Gardener

I am proud to publish these excerpts from PLANTING DIARIES by Sian Rees, a graduate of my writing course. Sian has created a fascinating horticultural blog exploring gardens, planting styles & their origins.

Follow PLANTING DIARIES

I am taking bookings for the next writing course, HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ on February 7th & 8th. Come to Spitalfields and spend a winter weekend with me in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Fournier St, enjoy delicious lunches and eat cakes baked to historic recipes, and learn how to write your own blog.

The Gardener, 1814

Stories about the real world and real lives were considered as interesting and exciting as fiction in children’s books of Georgian England. Trades were a popular subject – what people did and how things were made were described and illustrated with woodcuts, bringing these occupations to life for the young reader.

One such example is Little Jack of all Trades (1814) from Darton & Harvey, publishers of many children’s books from the later eighteenth century into the Victorian era. Author William Darton begins by likening workers in the various trades to bees in a hive, where everyone has their specific role to play within a larger inter-connected structure:

‘all are employed – all live cheerfully and whilst each individual works for the general good, the whole community works for him. The baker supplies the bricklayer, the gardener and the tailor with bread; and they, in return, provide him with shelter, food and raiment: thus, though each person is dependent on the other, all are independent.’

I was delighted to see that the book includes a profile of a gardener, who appears alongside other practical tradespeople such as the carpenter, blacksmith, cabinet maker, mason, bookbinder, printer and hatter – to cite but a few.

The gardener is portrayed handing a large bouquet of flowers to a well-dressed woman – most probably the wife of his employer. Our gardener is a manager – his two assistants behind him are engaged in digging over the soil and watering a bed of plants – while we learn his specialist skills include grafting and pruning.

In the background, a heated greenhouse extends the season for the production of fruits and other crops. Smoke from the building’s stove is visible rising from the chimney on the right. All the tools of the gardeners’ trade remain familiar to us today:

‘the spade to dig with, the hoe to root out weeds, the dibble to make holes which receive the seed and plants, the rake to cover seeds with earth when sown, the pruning hook and watering pot.’

From a contemporary perspective, it is interesting that Darton’s description of the gardener makes the connection between gardening and well-being:

‘Working in a garden is a delightful and healthy occupation; it strengthens the body, enlivens the spirits, and infuses into the mind a pleasing tranquillity, and sensations of happy independence.’

William Darton (1755 – 1819) was an engraver, stationer and printer in London and with partner Joseph Harvey (1764 – 1841) published books for children and religious tracts. His sons Samuel & William Darton were later active in the business.

Darton & Harvey’s books for children always contain plentiful illustrations, packed with details of clothes, buildings and interiors, that convey a powerful sense of working life in the early nineteenth century.

More recently, the status of gardening as a skilled trade has been undermined and eroded – so it is pleasing to see the gardener in this book taking his place on equal terms alongside other tradesmen.

The Basket Maker

The Carpenter

The Black Smith

The Wheelwright

The Cabinet Maker

The Boatbuilder

The Tin Man

The Mason

Images from The Victorian Collection at the Brigham Young University courtesy of archive.org

The Romance Of Old Bishopsgate

Thomas Hugo, the nineteenth century historian of Bishopsgate, wrote a history of this thoroughfare prefaced with a quote from his predecessor, John Strype in 1754 –“The fire of London not coming unto these parts, the houses are old timber buildings where nothing is uniform.”

While the rest of London had been rebuilt after 1666, Bishopsgate alone retained the character of the city before the fire and in 1857 Thomas Hugo was passionate that this quality not be destroyed – as he wrote in the strangely prescient introduction to his “Walks in the City: No 1. Bishopsgate Ward.”

“This quarter, so hallowed and glorified by olden memories, is unquestionably deserving of a foremost place in our affectionate regard. Our history, our literature and our art are associated with the charmed ground in closest and most indissoluble union. You can scarcely open a single volume illustrative of our national history which does not carry you in imagination to that still picturesque assemblage of edifices where, amid its overhanging Elizabethan gables and stately Caroline facades, its varied masses of pleasantly mingled light and shade, its frequent churches and sonorous bells, the greatest and best of Englishmen have successfully figured among their fellows, and to whose adorning and embellishment the noblest powers have in all ages been devoted.

And yet, unhappily, this is the spot where alterations are most commonly made, and with perhaps least regard to the irreparable loss which they necessarily involve. Here, where, for all who are versed in our country’s literature, every stone can speak of its greatness, where the name of every street and lane is classical, where around multitudes of houses fair thoughts and pleasant memories congregate as their natural home and common ground, the demon of transformation rules almost unquestioned, lays its merciless finger on our valued treasures, and leaves them metamorphosed beyond recognition only to work a similar atrocity upon some other precious object.

Special attention, therefore, on every account, as well as for beauty, the value, and the excellence of that which still remains, as for the insecurity and uncertainty of its tenure, is most urgently and imperatively demanded.”

John Keats was baptised in St Botolph’s Church, Bishopsgate.

The Bishop’s Gate was on the site of one of the gates to the Roman city of Londinium, from which led Ermine St, the main road north. First mentioned in 1210, Bishop’s Gate was rebuilt in 1479 and 1735, before it was removed in 1775. In 1600, Will Kemp undertook his jig from here to Norwich in nine days.

Crosby Hall, the half-timbered building at the centre of this picture was once Richard III’s palace. Other residents here included Thomas More, Walter Raleigh and Mary Sidney, the poet. Built by wool merchant John Crosby in 1466, it was removed to Cheyne Walk, Chelsea in 1910.

Elizabethan houses in Bishopsgate, 1857.

The Lodge, Half Moon St, Bishopsgate Without, 1857.

Paul Pindar’s House, Bishopsgate photographed by Henry Dixon for the Society for Photographing the Relics of Old London in the eighteen eighties. Paul Pindar was James I’s envoy to Turkey and his house was moved to the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1890.

Houses designed by Inigo Jones built in White Hart Court, Bishopsgate in 1610.

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

The Hoxton Chronicle

I am proud to publish these excerpts from THE HOXTON CHRONICLE by Steven Smith, a graduate of my writing course. Steven set out set out to explore his local neighbourhood through stories.

I am taking bookings for the next writing course, HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ on February 7th & 8th. Come to Spitalfields and spend a winter weekend with me in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Fournier St, enjoy delicious lunches and eat cakes baked to historic recipes, and learn how to write your own blog.

If you are graduate of my course and you would like me to feature your blog, please drop me a line.

Earl

SO LONG, CHEAP BOOZE!

Steven Smith celebrates the legendary ‘Cheap Booze’ off-licence

When Earl and his partners opened Cheap Booze at the corner of Haberdasher St and Pitfield St in 1991, it immediately became a local landmark with its huge green bottle sign made by the artist Matt Parsons. Earl comments that he would be rich if he had a pound for every photograph taken of it. Cheap Booze sells exactly what the name suggests – wines, beers, spirits, cigarettes and a small selection of sweets and snacks. It has a do-it-yourself feel. ‘Why spend money on the interior?’ Earl asks. ‘It will not sell a single extra bottle.’

Earl has prodigious energy, a broad smile and diverse interests in many enterprises. Somehow, despite the routine of running the shop, he finds time to pursue them all. He was born and grew up in Hackney, describing his childhood as ‘loosely supervised’, allowing him and his crew of close friends to roam freely in pursuit of whatever took their interest. Their shared passion was music. They pooled scarce resources to buy records and gradually assembled a powerful sound system from a mixture of bought, scrounged and self-assembled scrap materials.

While still in school, Earl and his friends were already performing gigs around London. The ‘Man & Van’ couriers, hired to ferry the vast sound system and record collection to venues, found it deeply puzzling to be contracted by children for serious late-night moving jobs to obscure locations. At sixteen, Earl’s schooling ended with a final gig at which he and his pals unveiled the massive sound system they had created to the amazement of fellow pupils.

Earl and his mates were now free to pursue their music full-time. However, Earl’s father had alternative plans, explaining to Earl that he was free to do whatever he wished but could only stay in the family home if he studied for a commercial trade. Surprised by this stern life lesson, Earl decided to take an apprenticeship as an electrician, reasoning that it might be useful in wiring his sound system. His friends were given similar parental injunctions too and became apprentice electricians too. On qualifying, they immediately established Heatwave Electrics, their own independent company. Work poured in, keeping them busy as electricians by day and DJs by night.

One day, whilst wiring a grocery store in Leyton High Rd, they realised they should open a shop of their own. Based on their collective observation that ‘everyone drinks’, they quickly hit on the idea of opening an off-licence in a vacant shop in Hoxton. Thirty-four years of Cheap Booze began with this moment of inspiration.

As the music side of life grew more serious with larger gigs, they worked to pioneer a new genre, blending reggae, ska, pop and rock to create what became known as Drum & Base Jungle music. Kevin Ford, a core group member since schooldays, became better known publicly as DJ Hype, recognised as one of the world’s foremost producers and performers of Drum & Base.

Music has taken Earl to almost every continent as a DJ. The trips were frequently long and arduous with a dozen flights between gigs in as many days, ending with a long-haul return flight to London in time to deliver him back behind the counter at Cheap Booze. Consequently, travel has become another of Earl’s passions that he is eager to indulge in future. The tropical landscape, and the calm and peaceful lifestyles of Ghana and Grenada are particular attractions. He confessed he may find his future in one of these locations. He says, ‘I have never worked for anyone, I am the centre of my business and can operate and prosper anywhere.’

After thirty-four years, Earl feels it is time for personal reinvention with a new enterprise. Given his outlook, robust energy and enterprise, he will surely prosper but Hoxton will be a duller place without him and Cheap Booze.

We wish him well.

The famous green bottle sign was made by artist Matt Parsons

Phil Maxwell In Liverpool

Contributing Photographer Phil Maxwell, whose book BRICK LANE we published in 2014, moved back from Whitechapel to his home town of Liverpool a few years ago and now has begun publishing his shrewd and affectionate images of the city in a series of photo books. The pictures below are from volume one which has just been released. Click here to buy a copy

‘I first came to Liverpool in 1972, aged eighteen, and remained for ten years. The city became my ‘University of Life,’ where I made friends, went clubbing, photographed the streets, listened to people a lot wiser than me, and grew up. It left an indelible mark on my consciousness and outlook on life, and it was the perfect place to begin my photographic journey.

Most of these photographs were taken on black-and-white film that I processed myself, and the rest on transparency film that I would post off to be developed and receive back a week later. Many of the places captured here have since been demolished and disappeared, but the memories associated with those places remain vivid thanks to the miracle of photography.

I moved from Liverpool to the East End of London in 1982 to the eleventh floor of a tower block near Brick Lane. The area was run down with derelict buildings, poor overcrowded housing, and resilient people trying to scrape together a living. I made friends, set about photographing the area and its diverse inhabitants, and began organising exhibitions of my work. I have taken more photographs of the East End than anywhere else and I still take photographs there several times each year, even after returning to Liverpool in 2015.’

-Phil Maxwell

Outside the Willowbank pub, 1982

Waiting for the Pope, Smithdown Rd, 1982

Waiting for the Pope, Smithdown Rd, 1982

Waiting for the Pope, Smithdown Rd, 1982

Waiting for the Pope, Smithdown Rd, 1982

Waiting for the Pope, Smithdown Rd, 1982

Bootle, seventies

Long Lane, eighties

Toxteth, 1975

Earle Rd, seventies

Long Lane, seventies

Off Picton Rd, seventies

Earle Rd, seventies

Picton, seventies

Near Princes Rd, seventies

Dingle, seventies

Rathbone Rd, seventies

Picton, seventies

Off High Park St, seventies

Photographs copyright © Phil Maxwell

The Kiosks Of Whitechapel

Mr Roni in Vallance Rd

As the east wind whistles down the Whitechapel Rd spare a thought for the men in their kiosks, perhaps not quite as numb as the stallholders shivering out in the street but cold enough thank you very much. Yet in spite of the sub-zero temperatures, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I discovered a warm welcome when we spent an afternoon making the acquaintance of these brave souls, open for business in all weathers.

I have always marvelled at these pocket-sized emporia, intricate retail palaces in miniature which are seen to best effect at dusk, crammed with confections and novelties, all gleaming with colour and delight as the darkness enfolds them. It takes a certain strength of character as well as a hardiness in the face of the elements to present yourself in this way, your personality as your shopfront. In the manner of anchorites, bricked up in the wall yet with a window on the street and also taking a cue from fairground callers, eager to catch the attention of passersby, the kiosk men embrace the restrictions of their habitation by projecting their presence as a means to draw customers like moths to the light.

In Whitechapel, the kiosks are of two types, those offering snack food and others selling mobile phone accessories, although we did find one in Court St which sold both sweets and small electrical goods. For £1.50, Jokman Hussain will sell you a delicious hot samosa chaat and for £1 you can follow this with jelabi, produced in elaborate calligraphic curls before your eyes by Jahangir Kabir at the next kiosk. Then, if you have space left over, Mannan Molla is frying pakora in the window and selling it in paper bags through the hatch, fifty yards down the Whitechapel Rd.

Meanwhile if you have lost your charger, need batteries or a memory stick in a hurry, Mohammed Aslem and Raj Ahmed can help you out, while Mr Huld can sell you an international calling card and a strip of sachets of chutney, both essential commodities for those on-the-go.

Perhaps the most fascinating kiosks are those selling betel or paan, where customers gather in clusters enjoying the air of conspiracy and watching in fascination as the proprietor composes an elaborate mix of spices and other exotic ingredients upon a betel leaf, before folding it in precise custom and then wrapping the confection into a neat little parcel of newspaper for consumption later.

Once we had visited all the kiosks, I had consumed one samosa chaat, a jalebi, a packet of gummy worms and a bag of fresh pakora while Sarah had acquired a useful selection of batteries, a strip of chutney sachets and a new memory stick. We chewed betel, our mouths turning red as we set off from Whitechapel through the gathering dusk, delighted with our thrifty purchases and the encounters of the afternoon.

Jokman Hussain sells Samosa Chaat

Mohammed Aslem sells phone accessories and small electrical goods

Jahangir Kabir sells Jalebi

Raj Ahmed

Mannan Molla sell Pakora

Mr Duld sells sweets and phone accessories in Court St

Mr Peash

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

So Long, Grace Payne

City of London resident Grace Payne died on 16th December aged 101. As a tribute, I am republishing novelist Sarah Winman‘s interview with Grace.

Grace Payne (1924-2025)

I was looking out from the thirty-sixth floor of one of the Barbican Towers. The clouds were low, and the City was trapped beneath a dismal fug. The spire of Christ Church, Spitalfields, was barely visible in the distance.

“You used to be able to see the Monument from here, but now it’s dwarfed by all the towers. Nothing is as it was, except perhaps the Honourable Artillery Company ground,” said Grace, as she placed the tea tray down and offered me a delicious homemade flap jack. “Not that everything in the past is necessarily good. If you go back far enough, it becomes a hell of a lot worse.”

“My Granny had four children and her husband died of consumption. Died like flies from overcrowding then. Mummy was only six. Granny ended up living in the Corporation Buildings in Farringdon Road – The old Guardian home – There was one parlour, one bedroom and a scullery with a copper pot, and a loo out the back. I can still smell the linoleum in that parlour.”

I had known the ubiquitous Grace Payne for five years then. We sang in a Community Choir together and the first things I noticed about her were her style, her elegance, and her irrepressible vitality. Over time I’d got to know a little about her working life, her sixteen years spent in Hong Kong, a little about her family. But that afternoon, over a pot of tea, she took me back to a time before.

“I was born in 1924. We lived in a condemned tenement building in Brixton,” she told me. “My father was in the police there. We then moved to Streatham and I went to Sunnyhill Primary School – think it’s still there actually. In 1934, my father was made Chief Inspector of a division at the Minories and we lived at the police station at number sixty. If you look for it now, it’s just a highway. I took a junior county scholarship for the City of London School for Girls, which was in Carmelite Street then. The headmistress was a Miss Turner: a slim woman, hair in a bun, flat buttoned shoes, dressed in purple, you know the type. Wouldn’t allow a book to be placed on top of the bible in her presence! It was quite a snobby environment, and I had rather a South London accent. My mother, a working class woman, went to meet Miss Turner and was asked, ‘What would happen about the fees if your husband lost his job?’ So insensitive. They recommended me to have elocution lessons.”

“I used to travel from Mark Lane Station (now Tower Hill) to Blackfriars. There were no school friends or neighbours who lived near me, except my friend Olga Raphalowsky who lived in Spitalfields. They were White Russian Refugees. Her father was a GP and they lived over the surgery. This family was like another world to me. Thick accents, intellectuals, wonderful and friendly – so exotic, not at all English. Uncle Danny was a film maker! I was still friends with Olga up until she died two years ago.”

“Oh I’ve stayed in touch with many of my school friends – Margaret and Mary, and Hazel Morris. I suppose wartime brought us together. In November 1940 we were evacuated to Keighley in Yorkshire. We waited in the church hall for one’s name to be called out and for someone to take you home. Margaret and I were billeted together with a family called Lumb. We were there for two years with the mother and father and three year old Jean. Well, Jean comes to stay with us now when she comes to London. She must be nearly seventy-three.”

“Keighley was grim. War was pretty bad by then and rationing tight. Coal was in short supply and homes were cold. But Margaret and I used to go into Bradford for the Hallé concerts. Henry Wood was conducting one night and he apologised for wearing a lounge suit. He explained that his suitcase had been lost on the train and that’s why he didn’t have his proper dress.”

“Before evacuation, however, we’d gone to live in Snow Hill police station because my father had again been promoted. He was in charge of all the ARP warden’s too. There was sticky tape across the bow windows and sandbags piled out the front. The police station had a flat roof and I used to collect shrapnel that had fallen during the night. I had a great collection. One morning, I found cans of fruit on the roof that had blown over from an exploding warehouse. I used to sleep in the basement and my parents slept at the back. A bomb fell on our building in September 1940. It was 10:30, 11:15 at night, I think. Four bombs were dropped all in a line – one hit the Evening Standard building, another St Bart’s hospital, another I can’t remember, but the last fell on us. I remember my parents coming out covered in dust.”

“From my school days until now, the one thing I’ve always done is sing in a choir – maybe with a few gaps. But my father always sang in a choir. He started the City of London Police Choral Society, started it during the war. He sang at Douglas’s and my wedding. We were married in St Bartholomew the Great Church. It was wonderful, didn’t cost an arm and a leg in those days – The film “Four Weddings and a Funeral” changed all that. Cost us seven shillings and sixpence, I think.”

“We didn’t consciously move back to the Barbican after our travels. We were living in South Kensington. But when we got to the age of seventy, we were nagged by one of our daughters to move before one of us had a stroke or something! But I can’t imagine not living here. At our age there’s so much to do. If we lived in the country what the hell would we do?”

There was a moment to pause, and I wrote: City of London Old Girl, Imperial College Old Girl, wife, mother, university teacher, text book writer, traveller, jewellery maker, and all round good egg.

“Anything else, Grace?” I asked.

“Grandmother and great grandmother,” she said. “Family, it’s the thing that matters most of all. Everything else is rather trivial in comparison,” she said and she smiled. And I know she was right.

I looked up from my notebook and realized hours had passed. Night had fallen. We sat quietly as lights erupted across the spent City.

“I was also a model, you know,” said Grace matter-of-factly.” Must have been seven because after that I cut my hair and they didn’t want me then. I modelled for a Couture House in Bond Street – ‘Russell and Allen’s’ – I came up on the tram from Streatham, lovely to have a day off school. Also modelled for Paton and Baldwins’ knitting patterns.”

I took another succulent flap jack. I was happy. Grace Payne I salute you.

Home made flapjacks following a sixty year old recipe.

Grace’s first teddy bear.

Grace in her kitchen jewellery workshop.

Grace in her modelling days.

Grace at the Police Sports Day around 1930.

At Sunny Hill Road Primary School.

Grace’s father

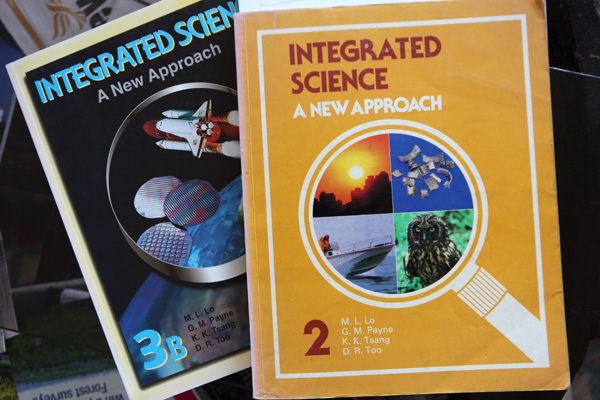

Science text books from Hong Kong co-written by Grace.

Grace Payne

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

The Gates Of The City

Click here for more information about my writing course on 7th & 8th February

I came upon these handsome Players Cigarette Cards from the Celebrated Gateways series published in 1907. As we contemplate the going-out of the old year and the coming-in of the new, they give me the ideal opportunity to send you my wishes for your happiness in 2026.

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of cigarette cards