Niki Cleovoulou, dress designer

Niki has always been a perfectionist, since she first learnt sewing and pattern cutting in Cyprus before coming to London at the age of thirteen in 1959. “I could never pass any faults. I don’t care about the money, I don’t care about the time, I don’t care about the trouble, so long as I can do something good for the customer, then I can be happy.” she declared with a grin of satisfaction, speaking of her work today as a designer and maker of haute couture gowns for special occasions – in plain words, a traditional dressmaker.

“I couldn’t go to school because of the war in Famagousta,” revealed Niki regretfully, giving the reason for her journey across Europe in her early teens, leaving the village of Styllous to live with her brothers in Neasden, who were students at that time.“Within three days they took me to the factory in the West End where my older sisters worked. I was a machinist, making skirts for ladies’ suits.” she told me. And so Nikki’s working life in London commenced, and the photograph above serves to illustrate this time eloquently, revealing Niki as a poised young woman of modest temperament, full of life and anticipation at the possibilities of existence.

In those days, Niki’s godfather Sophocles came regularly to the Spitalfields Market to buy fruit and vegetables, and he always got his hair cut by a young bachelor Kyriacos Cleovoulou at the salon in Puma Court. It was a chance meeting that was to decide the course of Niki’s life, because their respective families decided to put Niki and Kyriacos together. “They came over to see my family in Neasden. It was very difficult for us to go outside or even be alone,” admitted Niki, rolling her eyes with a blush and a shrug, “It was arranged, we got engaged within two or three weeks and married three months later.”

“We came to live here in Spitalfields in 1970, but the building had to be fixed up because it was in a poor state and we did the salon first. I remember the men with barrows of fruit and vegetables running around shouting at four in the morning, and people going to cafes for breakfast early. You could do your shopping at dawn. It was very friendly, like a family. My husband used to go and buy boxes of fruit, he knew everyone and they knew him because they all came here for haircuts! He used to open very early in those days.

A year after we were married, we went to Cyprus together for two months and when we came back he stopped cutting hair and worked with me in the factory, where I taught him how to sew trousers. But then the factory burned down, so my husband went back to hairdressing, ‘Hairdressers always have money in their pocket.’ he used to say, because he never had to wait until pay-day as other professions did. He set up a sink and all he needed was a comb and scissors to earn money.”

Although Niki held great affection for the sociable life and community that she encountered living in proximity to the market, she was less enthusiastic about the living conditions in the tiny rooms above the salon in Puma Court where she brought up her two young sons George and Panayiotis, while still doing sewing from home. “It was very difficult, there was no bathroom – so my husband fixed one up in the hallway and we had a kitchen at the back.” she confided, thankful that within five years they were able to buy a house in Palmer’s Green and Kyriacos could commute on the train to Liverpool St each day.

Throughout all these years, Niki earned money through her sewing and yet, as she confessed to me, she was secretly frustrated because she never got to design dresses as she had always wished, “I was doing my dress designs but only for the people that knew me. I thought, ‘If only, if only everyone knew what I could do, I could make a dress for the Queen’ – I had so much confidence in myself and my gift.” Niki never gave up her ambition and, even though she was qualified in pattern cutting in Cyprus, she achieved a City & Guilds’ Diploma that qualified her in this country too. Then, just ten years ago, working in partnership with her daughter Stavroulla (widely known as Renee) she created Nicolerenee, making bespoke wedding dresses and gowns for special occasions, working from the old family premises in Puma Court.

My conversation with Niki took place over a cup of tea in a quiet corner of Cleo’s Barber Shop, the salon where her husband Kyriacos began cutting hair in 1962 – where her godfather Sophocles came for a haircut in 1969 and discovered that Kyriacos the barber was an eligible bachelor. It is a location charged with powerfully emotional resonance for Niki and now, five years after Kyriacos’ death, their three children, Panayiotis, George and Stavroulla have reopened the barber shop, continuing the tradition for a second generation. When the time came for Niki’s portrait, we walked through to the premises next door, once derelict, now a showroom full of elegant silken gowns arrayed upon rails, all examples of Niki’s talent and expertise. Here Niki took out a favourite pink dress, full of proud memories, that she made for herself and wore frequently in the nineteen sixties, still in immaculate condition today.

This is a story that shows how external events can affect a life, sending Niki from Cyprus to London and from Neasden to Spitalfields, while equally illustrating the power of resolute self-belief to overcome obstacles. As Niki confirmed when she held up the dress in triumph, cast her eyes around the rails of dresses filling the tiny shop and said with a gleeful smile, “In the end all my wishes have come true, because I have the shop here today with my daughter, and I am a very happy person, especially when I can talk about my work!”

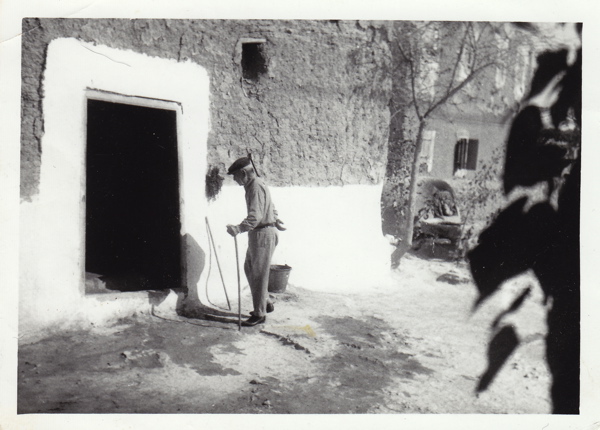

Niki on a visit to her childhood home in Styllous, Famagousta, Cyprus in 1966

Niki’s father George, 1966.

Kyriacos at the Acropolis, early sixties.

Niki and Kyriacos outside St Andrew’s Church, Kentish Town on their wedding day, 1969.

Kyriacos and Niki

Cleo’s Barber Shop in Puma Court, Spitalfields, nineteen eighties.

Kyriacos stringing beans in the yard at the back of the salon between haircuts, ten years ago.

Niki Kleovoulou today.

Photograph copyright © Jeremy Freedman

You may like to read my earlier story about Cleo’s Barber Shop

Spitalfields Antiques Market 16

This is Hollie Reedy, a sassy young New Zealander who possesses an arresting knack with eyeliner and always dresses in black. “I have lots more stuff at home, but what you see is what I can carry in two black bags on the bus from the Kingsland Rd.” she enthused, while adopting a series of fashion plate postures with an endearing lack of self-consciousness. A restless nomadic spirit, Hollie confessed with an eager smile, “I used to have a shop in New Zealand, but I shut it to come here and brought the stock with me, and now I am ready to go back and start again in Auckland.” Catch this exotic migratory bird with the raven plumage before she flies off to another hemisphere.

This is my pal Bill, a dignified market stalwart who deals in coins, antique whistles, gramophone needle boxes, souvenir thimbles, magic lantern slides, trading tokens, small classical antiquities and prehistoric artifacts. “I sell quite a few things, but on a low margin because it’s more interesting to have a quick turnover.” he admitted to me, speaking frankly, “I’m here more for enjoyment really – quite a few friends I’ve made over the years. I was a shy person before, but it’s made me confident having a stall. I’ve become an optimistic person.” Bill travels from Walthamstow to Spitalfields each week with all his stock in a backpack and large suitcase – practical, economic and an incentive to sell as much as possible.

This is Barrie Reeve, a bold adventurer who scours Belgium and Holland, exploring the stranger margins of the trade – with eclectic finds such as the medical specimens and charts, chemistry jars, maps and artificial limbs you can see in the picture, which delight the bohemian tastes of his specialist customers here in Spitalfields. I especially liked the orrery on the top right with all the planets made of little wooden balls on wires turning round a tin disc, a primitive model of the grandest scheme of all. Surrounded by his marvellous discoveries, Barrie exudes a proprietory largesse, proud to share his appreciation with aficionados of the offbeat.

This is Richard Rags and his appealingly voluble son Cosmo Wise, both dressed head to toe in the clothing from the nineteen forties and earlier that is their shared passion. They cherish the extravagantly worn-out old togs your grandparents discarded, full of vibrant character and handmade details no modern garment can ever match. Cosmo really knows how to wear it and, with admirable enterprise, is now copying his most treasured finds in old fabric, to create exclusive pieces sold under his own label “De Rien.” “We are drowning in clothes, clothes dripping from the ceiling, even beds made of clothes.” he revealed with barely concealed delight, divulging the singular living conditions at their clothing warehouse in Hackney Wick.

photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

More East End Shopfronts of 1988

There is an astonishing contradiction in this photograph – taken by broadcaster Alan Dein on Alderney Rd, Stepney in 1988 – between the elegantly written surname upon an eau-de-nil ground, full of majestic promise, and the overstated brutality of the breeze blocks filling the shopfront, intended to shut it down and shut us out, irreversibly and forever. Yet in spite of the pathos of the image, Alan admitted it was “a kind of bliss for someone like myself who was documenting the ramshackle and the uncelebrated.”

This picture is another of the compelling photographs in the remarkable unseen collection of more than one hundred East End Shopfronts by Alan Dein, from which I am pleased to publish a second selection for you today. Alan was twenty-seven years old when he embarked upon the project, inspired by the work of Eugene Atget, Walker Evans and Bill Brandt, whose work he encountered through well-thumbed copies of monographs of their beautiful photographs in the Art & Music department on the top floor of the former Whitechapel Library.

“From my room in White Horse Road, Stepney I could find so many places close-by that fascinated me at that time. My favourites were shop fronts – particularly the ones with Jewish names, though once I’d run out of those (their era had already passed by), I’d be on the look-out for anything that was pleasing to my eye. Looking back, my motivation was to capture their last moments on earth. I was and I still am, a devotee of ’junk’, and at that time the battered and the worn-out were almost anonymous in a landscape that still resembled a scarred battleground of the WWII Home Front.

The surviving shops didn’t have long to live. These are the last breaths of these little places, before succumbing to the pincer-like squeeze of the Docklands Development Corporation on one side, and the encroaching eastward sprawl of the hungry City upon the other. But the end for many of them had come earlier, as the proprietors retired, moved away or died, and significantly their children wished for another way of life beyond the four walls of the parents’ shop.”

Each of these shops had their heyday and those images would tell a very different story, of the world inhabited by Alan’s grandparents before the Jewish people left the East End, turning their backs on the history of poverty as they moved to newly built suburbs. This earlier world was accessible to Alan only through reluctant family reminiscence. But when he came to walk around the streets of East London, seeking for himself the remnants of the Jewish East End culture in which his family had its origins, he found closed-up shops that acquired a strange beauty for him.

There is an elegiac poetry in every one of these shopfront images, unsentimental in their formal compositions and inscrutable facades – boarded up to exclude squatters or thieves. They show the texture and patina evidencing the activity of those who have gone, and the confident colours and outdated signwriting dramatizing pitifully redundant aspirations to seek “exclusive tailors” or to “get tuf here”.

The shutter in Alan Dein’s camera became the final curtain that fell upon an unknown drama, framed by the proscenium of each shop window. The actors had gone, the stage was bare, they were theatres only of memory and no more performances would be played, yet Alan’s achievement was to record the human presence that remained.

“Posner’s in Commercial Rd was just round the corner from where I lived – once the site was gutted, an estate agent moved in, selling and renting properties in the Docklands.”

Stepney Green. “Only recently closed – you can see a hand-written flyer for the Half Moon Theatre in the window.”

Alie St

Hackney Rd

Mile End Rd

Alie St

Brick Lane (see Suskin’s Wilkes St premises in the previous set of pictures)

Commercial St

“I used to buy my shoes at Schwartz’s, trading on the Mile End Road, just by the old Half Moon Theatre. It was lovely to think that these places which resembled those old Ladybird book-style shops of the fifties and sixties were hanging on into the eighties.”

Bow Common Lane

Ben Jonson Rd. “A twilight zone where the shops built underneath the post-war housing blocks were still selling goods from a past age.”

Bow Rd

Here are just two of the many Levy’s that once existed on the streets of East London, above in Ridley Rd and below in Goulston St.

photographs copyright © Alan Dein

Take a look at more of Alan’s pictures here Alan Dein, East End Shopfronts 1988

Up the tower with Rev Turp

Who would have dreamed there was as much as two hundred and fifty tons of ironwork inside the tower of George Dance’s St Leonard’s Shoreditch? This edifice, completed in 1740, does not impose itself monumentally upon the High Street, and yet, comprising seventeen hundred tons of masonry, with walls eleven feet thick, it is as awe-inspiringly vast a structure as any parish church tower could be – as I discovered for myself, when I had the privilege of a guided tour by Reverend Paul Turp that led me up and up and up.

Following in the Rev Turp’s footsteps – picking up where we left off at the end of my subterranean adventure at St Leonard’s – I walked into the entrance of the church and slipped through the narrow door to the tower, next to the seventeenth century stocks and whipping post. Ascending the cramped stone staircase in the thickness of the wall, spiralling upwards towards the ringers’ chamber, I could not resist poking my head round the door of the dark and dusty room behind the clockface. As with the space beyond the cinema screen, there is an intriguing enigma about the hidden world behind the clock, like standing inside an eye, with external vision obscured by the single image upon the lense.

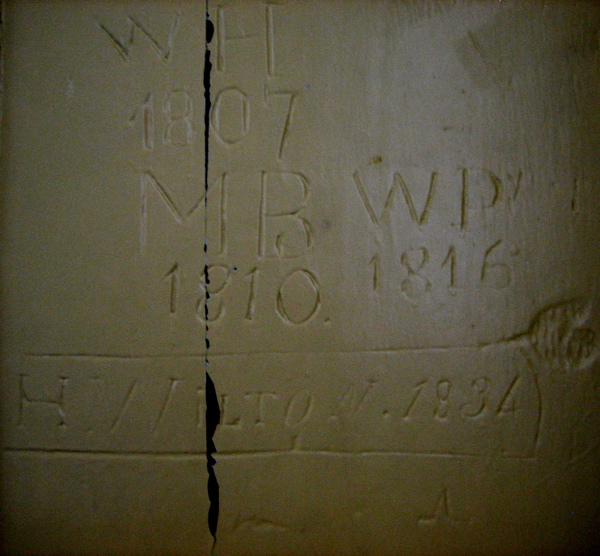

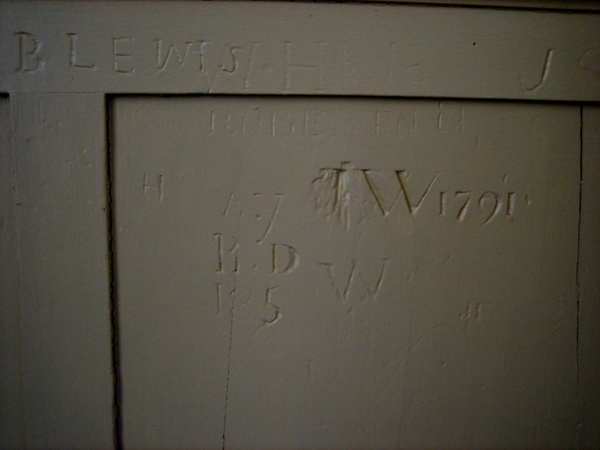

While Rev Turp expounded enthusiastically about his magnificent thirteen bells, named after the twelve apostles plus Andrew and rung more than any other church bells in the South East of England thanks to a set of shutters that spare the neighbours from the clamor, my eyes wandered to explore the eighteenth and nineteenth century graffiti upon the panelling. Men’s names and initials were incised in confident block or italic letters. There is nothing furtive about these carvings, suggesting those responsible were bellringers or other church officials, confident of their right to be here and leave modest inscriptions for perpetuity.

Ascending further up the spiral staircase, we came to the place where the stone steps ended at the foot of a metal ladder leading into the steel bell frame itself. Here we stood upon a grid of hefty iron girders from which the bells hang, each mounted upon a massive wheel, turned by ropes pulled in the chamber below. Now, it was as if we were interlopers within the workings of a giant clock, dwarfed by ranks of wheels and gleaming bells on either side. This is where Rev Turp lowered his voice to issue a warning – explaining that there was no obligation to go any further – and when I saw the narrow old wooden ladder roped in place, ascending diagonally across the space, it did cause me to think twice. “I don’t want you falling and damaging my bells,” declared the Rev, wagging his finger with droll humour, before setting a bold example by clambering swiftly up the precarious ladder with the unique confidence of one who has a special relationship with the almighty.

Inspired by the Rev’s example, I set out confidently upon the ladder too, only to find myself unexpectedly in a vast dark chimney, standing upon a few planks creating a makeshift platform within the bare internal shaft of the tower. Here I made the mistake of looking down through the floor to the bell frame far below. I did not want to fall and damage the Rev Turp’s bells. Recovering myself, I discovered another ladder in the gloom leading upwards to a square of daylight where the Rev Turp stood, like St Peter, waiting to greet me with a welcoming hand, once I had transcended the final level. Concentrating on holding the rungs firmly, as the Rev taught me, so that if one should break I could hold my own weight and my hands would not slide down the slides, I climbed safely to the top of the ladder.

Just as in those fairground rides which induce an accumulation of tension only to deliver a powerful rush once the pinnacle is reached, I was exhilarated to arrive at the top of the tower and look out across the expansive roofscape of Shoreditch, with Spitalfields and the City of London beyond. Where a moment before, I was gripped with a sense of my own vulnerability, now I could survey my fellow humans as if they were ants beneath my feet. The new overland rail line, so many years in construction, was a mere toy for our amusement from up here. “Look there goes a train!” pointed out the Rev in childlike delight.

Yet the humbling evidence of greater forces was here in the lumps of grey shrapnel, some as large as potatoes, buried in the stonework at the very top of the tower. The blast of World War II bombs was sufficient to propel debris to this height and embed them in stone. Changing tone, the Rev described how during the burning of London, the heat was so great that people took refuge in the crypt to escape the flames of Shoreditch High St. When he was a young priest, Reverend Paul Turp spent many hours up here in this eyrie (explaining his nimble confidence within the tower today), from whence he surveyed his whole parish, learning more about his community from this vantage point, because the physical composition and social contrasts of the neighbourhood are more apparent from above than at street level.

Returning to earth again, my legs turned to jelly, briefly unaccustomed to merely walking upon the pavement. In spite of the insights Rev Turp had granted me, I was relieved to be back, because I am not a burrowing creature that feels comfortable under the ground, nor am I a fowl that can soar effortlessly up into the sky, but one that delights to walk with my own two feet upon the plain surface of the earth.

World War II shrapnel embedded in the stone at the top of the tower.

Shoreditch High St from above, looking towards the Barbican.

Graffiti in the bell ringers’ chamber.

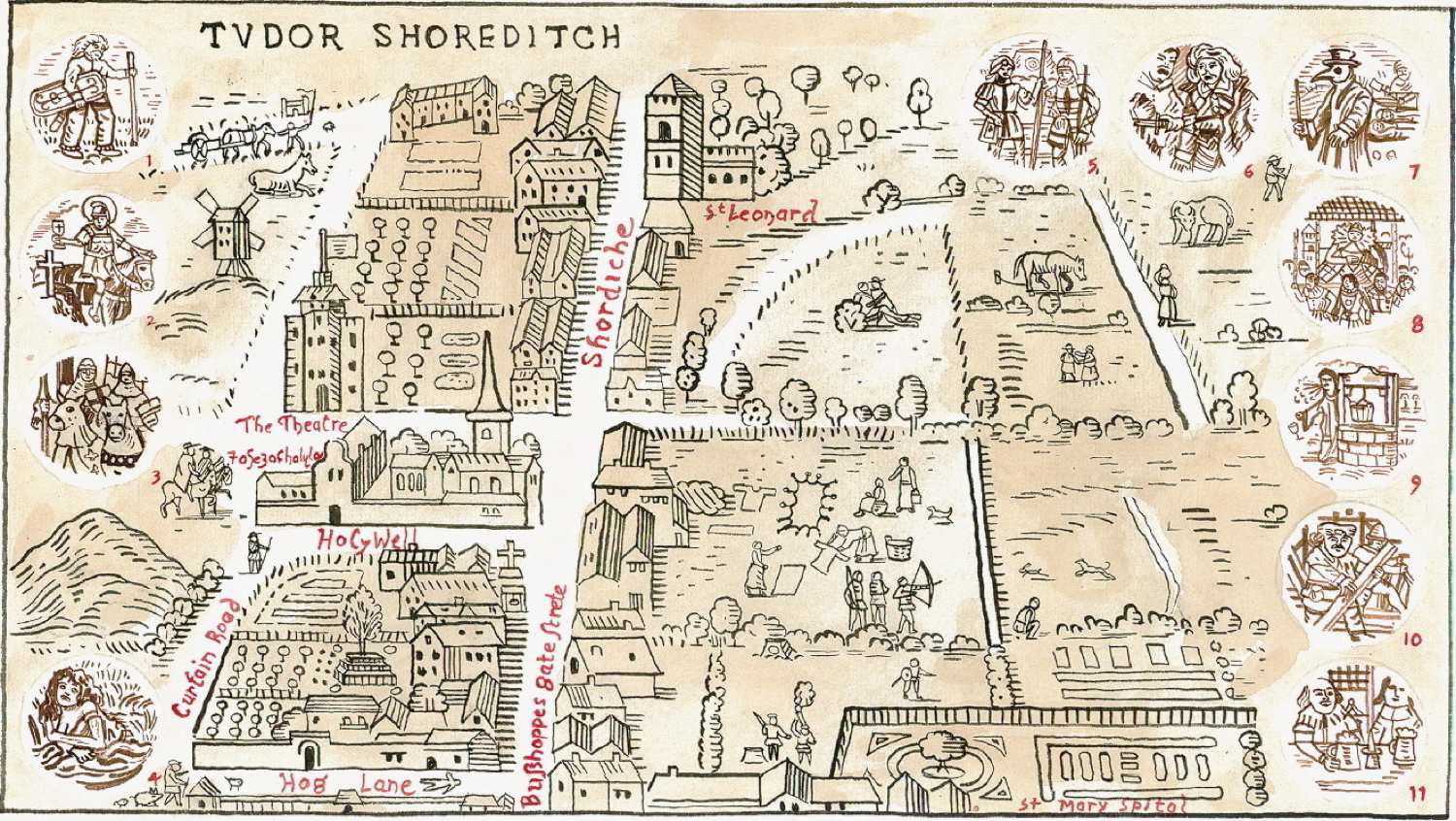

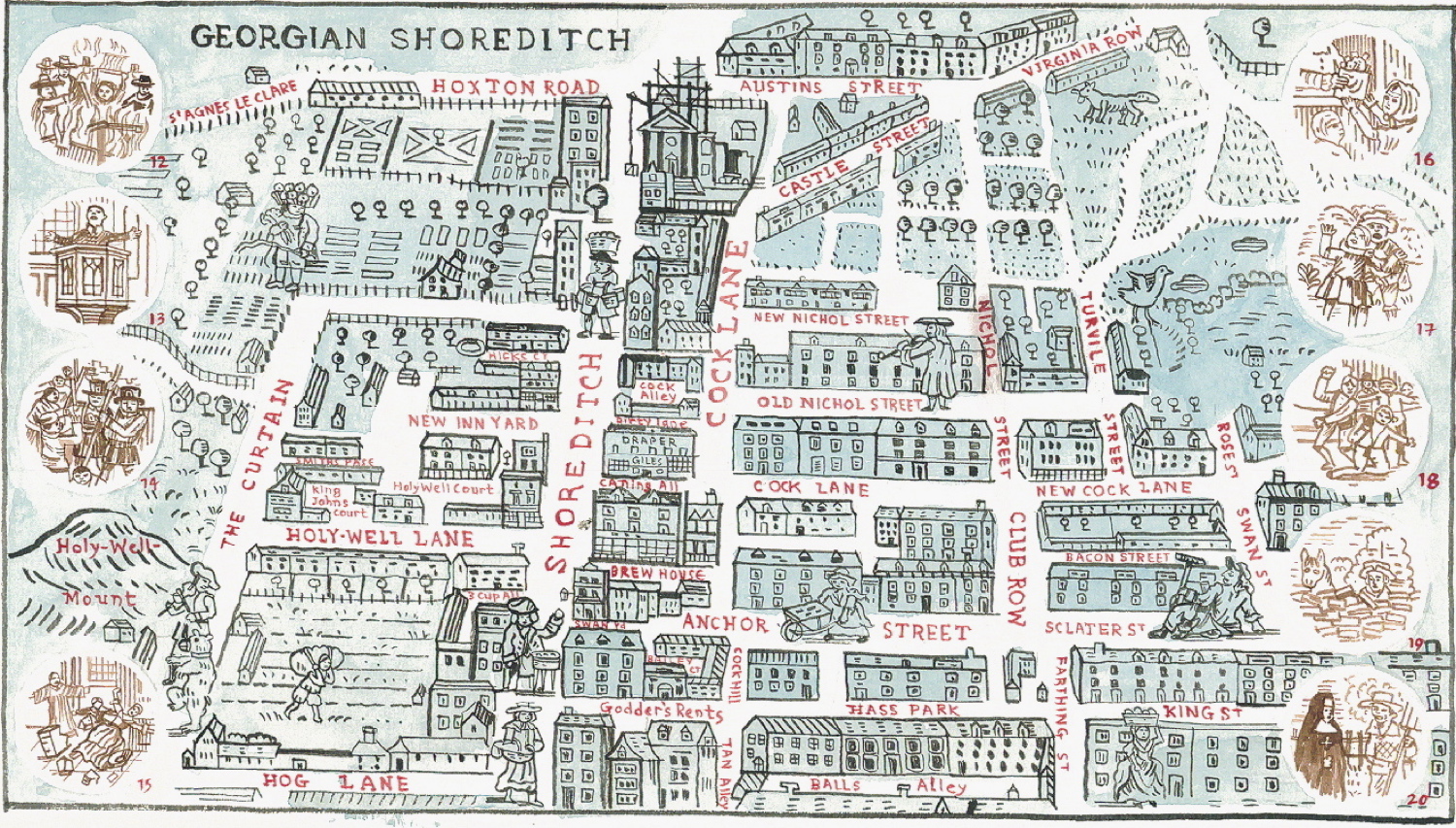

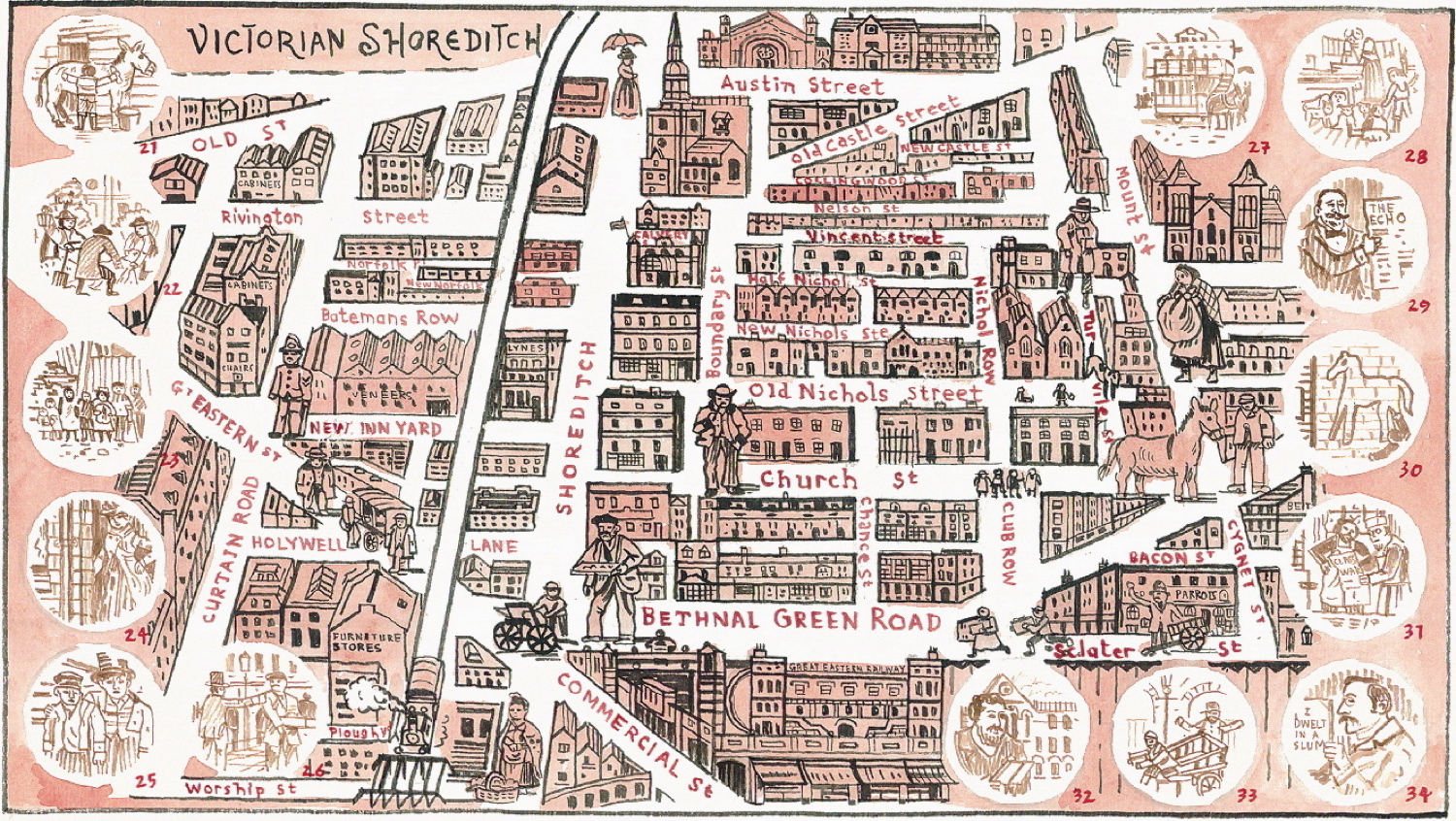

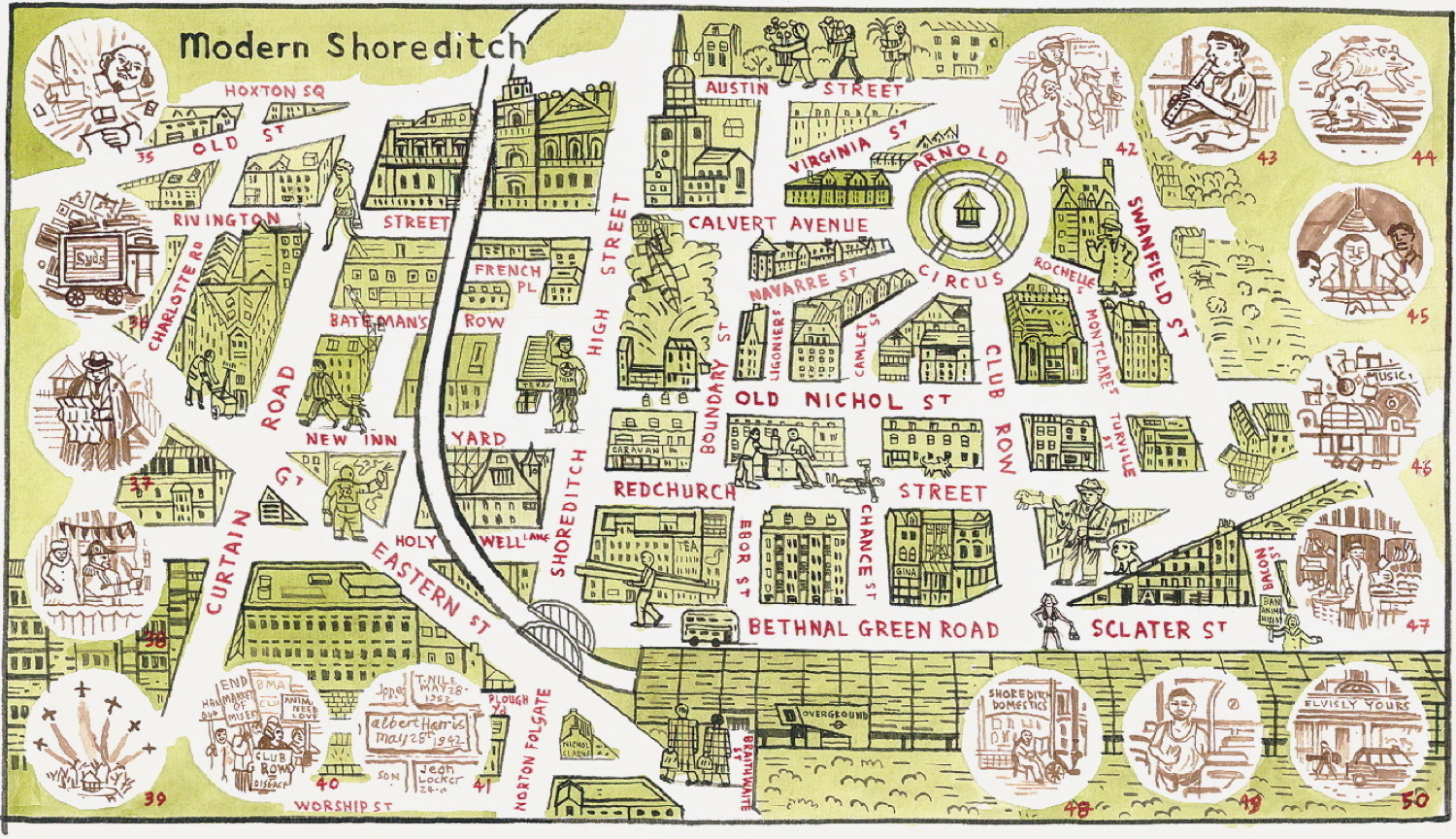

Adam Dant’s Map of Shoreditch

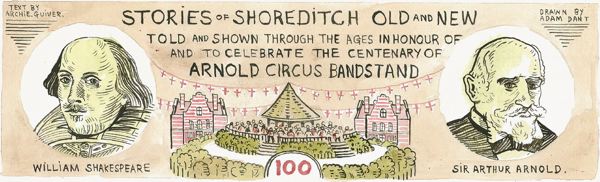

It is my delight to publish Adam Dant‘s map drawn to celebrate the centenary of the newly renovated Arnold Circus bandstand.

1. Iron Age Man establishes a track along what is now “OLD STREET”.

2. Christian Roman Soldiers worship at the source of the river Walbrook, now St Leonards.

3. Sir John de Soerditch rides against the French Spears alongside The Black Prince.

4. Jane Shore, a goldsmith’s daughter & lover of Edward IV dies in “a ditch of loathsome scent.”

5. “Barlow” the archer is given the dubious title “Duke of Shoreditch” by Henry VIII.

6. Christopher Marlowe murders the son of a Hog Lane innkeeper, he escapes prosecution.

7. Plague burials take place at “Holywell Mound” by the Priory of St John the Baptist at Holywell.

8. Queen Elizabeth I on passing by medieval St Leonards is “Pleased by its Bells.”

9. The sweet water of “The Holywell” is spoilt by manure heaps of local nursery gardens,

10. James Burbage’s sons Cuthbert & Richard dismantle “The Theatre” in two to four days & transport it to the South bank of the Thames where it is rebuilt as “The Globe”.

11. William Shakespeare enjoys a “bumper” at an inn on the site of the present “White Horse.”

12. Local Huguenot weavers riot for three days protesting against & burning “multi-shuttle looms”.

13. Thomas Fairchild, a gardener, donated £25 to St Leonards for an annual Whitsunday sermon titled “Wonderful Works of God in creation” or “On the certainty of resurrection of the dead proved by certain changes of the animal and vegetable parts of creation.”

14. Militia are called from the Tower to quell four thousand Shoreditch locals rioting against cheap Irish labour being used to build the new George Dance tower of St Leonards.

15. Large lumps of masonry fall onto the congregation during a service at the collapsing old St Leonards.

16. The Huguenot speciality “fish & chips” appear at Britain’s first fish & chip shop on Club Row.

17. The many murders & muggings at Holywell Mount lead to it being levelled.

18. Local theatres such as The Curtain sink to become “no more than sparring rooms.”

19. Brick Lane takes its name from local brickfields, occasional location of furtive criminality.

20. Visitors to James Fryer’s land at Friar’s Mount wrongly assume a monastery stood there.

21. Joe Lee, the local horsewhisperer, coaxes improved productivity from working donkeys.

22. “Resurrection Men,” notorious body snatchers pinch recent interred corpses from St Leonards, some coffins in the crypt are found to contain bricks instead of bodies,

23. Four thousand people are dispossessed as Bishopsgate Goods Yard replaces streets around Swan Lane & Leg Alley.

24. Mary Kelly’s funeral procession leaves St Leonards amidst huge crowds. The poor victim of Jack the Ripper is given a second funeral at her own catholic cemetery.

25. Oliver Twist is said to have resided in Shoreditch. Many other unfortunate children arrive each morning at The White St Child Slave Market seeking work.

26. So many unruly pavement-side street vendors populate Shoreditch High St that a regular uniformed Street Keeper is employed.

27. Horse drawn trams add to the general commotion bustle and smell of the High Street.

28. Cats meat sellers, watercress hawkers & dog breeders all cram into the Old Nichol’s filthy tenements.

29. Sir Arthur Arnold, head of the LCC main drainage committee is commemorated at Arnold Circus.

30. For decades the chalk horse on Bishopsgate Goods Yard is redrawn by unknown local artist.

31. Enthusiastic Anarchists hoping to bring political awareness to the Old Nichol proletariat through their Boundary St printing operation find the task “like tickling an elephant with a straw.”

32. Artist, Lord Leighton calls the interior of Holy Trinity, Old Nichol St, “The most beautiful in England.”

33. Arthur Harding’s memories of his slum boyhood, “van dragging” etc are recalled in “East End Underworld.”

34. Arthur Morrison pens his slum tale “Child of the Jago” following Reverend Jay’s invitation to the Old Nichol.

35. The chapel dedicated to Shakespeare on Holywell Lane is destroyed by a WWII bomb.

36. Syd’s Coffee Stall, now Hillary Caterers, is saved from destruction during an air raid as two parked buses shelter it from a bomb blast. Thomas Austen’s medieval chancel window is less fortunate.

37. Novelist Arthur Machen identifies a “leyline” running through the mystic ancient earthwork Arnold Circus.

38. King Edward VIII officially inaugurates Boundary Estate from a platform on Navarre St.

39. The Red Arrows pass over the bandstand en-route once more to the Queen’s Birthday.

40. Protestors eventually force the closure of Club Row animal market, once home to dogs, parrots, pigeons and the occasional lion cub.

41. Navarre St is used as a playground by children who carve their names into the brickwork.

42. Artist, Ronald Searle visits Club Row animal market to illustrate Kaye Webb’s “Looking at London.”

43. The resident Bengali flute player of Arnold Circus is often heard across the Boundary Estate on warm Summer evenings.

44. The IRA bomb which explodes on Bishopsgate disturbs the rats in Shoreditch who emerge in large numbers from the drains,

45. The great train robbers plan their notorious crime upstairs in The Ship & Blue Ball, Boundary St.

46. Jeremiah Rotherham demolishes the Shoreditch Music Hall for another warehouse.

47. Joan Rose‘s father proudly displays his fruit & vegetables on Calvert Avenue whilst she is sent to buy more bags at Gardners Market Sundriesmen (still trading today).

48. Every type of vacuum cleaner bag is sold by “Zammo from Grange Hill’s dad” at Shoreditch Domestics on Calvert Avenue.

49. The failed Suicide Bus Bomber is seen by security camera leaving the No 26 at Shoreditch.

50. Mono-recording virtuoso, Liam Watson strides past Shoreditch’s “Elvisly Yours” souvenir shop en-route to legendary Toe-rag recording studios in French Place.

Maps copyright © Adam Dant

Columbia Road Market 44

I returned from the market laden with fifteen of these Geraniums (Vancouver Centinial) that I bought for ten pounds. “Ah’m givin’ ya’ twen’y five quid’s worth fer a tenner,” explained the plant seller with the characteristic magnanimity that distinguishes the traders of Columbia Rd. It gave me a dozen for my window box, one for a pot on the dresser and two as a gift for my neighbour. Geraniums are the most egalitarian of plants, and so I was delighted to have surfeit of them, thanks to the keen prices at Columbia Rd Market.

Years ago, I used to restrict myself to just white Geraniums. A shameful aberration that I have now thankfully renounced, embracing the glorious gaudiness of the red Geranium. The smell of their leaves is irresistibly evocative with its delicious bitter scent, and it was the dramatic variegated foliage which attracted me to this particular variety, as well the vivid scarlet flowers.

For months, I was wary to replant my window box for fear of disturbing the family of Blue Tits that nested in my bird house this Spring, but they have safely flown weeks ago, and I have been seeing the mature young birds flying around the garden. Now my window box is ablaze with a mass of flaming red Geraniums, greeting me as the first glimpse of life that I see upon waking each morning, to inspire me to roll out of bed and seek the day.

Who is Arnold Circus?

It is my pleasure to publish A Guide to Arthur Arnold, his Brother and his Circus by Naseem Khan of The Friends of Arnold Circus, written to celebrate the centenary of the bandstand on the Boundary Estate, Britain’s first social housing estate.

The newly renovated bandstand will be inaugurated tomorrow, Sunday 18th July, with a Sharing Picnic from 1pm, to which all are invited. Joan Rose will cutting a cake and I will be distributing a thousand copies of a free booklet containing stories from Spitalfields Life about Arnold Circus, so please come along and join the party.

Arthur Arnold didn’t look anything like this child’s version of the man behind Arnold Circus. But he did share qualities of energy and originality with the drawing. Robert Arthur Arnold was a resolute campaigner – a man who set great store by social justice and who spent much of his sixty-nine years working to improve the lives of the under-privileged in Victorian times. Arnold Circus is part of his legacy.

Looking at his track-record, you might not immediately think he was an innovator. His CV at first looks deceptively worthy – assistant commissioner under the Publlc Works Act (1863), author of a well-regarded pamphlet analysing schemes for the Thames Embankment, Liberal MP. But look a bit deeper and a man of persistent vision, a sturdy sense of commitment and a strong streak of independence of mind and unpredictability.

For this apparently solid Victorian public servant also produced two sensational novels, fought for married women’s rights at a time when they were legally subservient to their husbands, started and edited one of the first London evening newspapers, The Echo, and – when it was sold in 1877 – set off, with his wife, on a thousand-mile long trip, by horse and camel, the length and breadth of Persia.

So which is the real Arthur Arnold? Was it the pubic servant who concerned himself with decent sewers, good housing for the poor and land reform so that every farm worker could have the right to ‘three acres and a cow’? Or was it the independent-minded man who married the pioneering writer, Amelia Cole, and who in 1900 – at the height of the Empire – wrote how much he disliked the term ‘imperialist’ because ‘to me it is always suggestive of a waxed moustache’? And what did Arnold have to do with the circular gardens and bandstand at the heart of the then very new Boundary Estate?

The last one is the easiest question to answer. When the London County Council was formed in 1889 as the first all-London government, Arthur Arnold was elected as an alderman. In 1895, he became Chairman of the body and was involved in its pioneering ventures. Determined to be a progressive force, the LCC early on voted to demolish the notorious East London slums of The Old Nichol and replace them with the very first social housing estate, to be a model for good municipal government. Naming the gardens at the heart of the Boundary after Arnold was a graceful acknowledgment of his role.

It also has an element of irony, for Arnold had actually opposed the municipal housing policy since he argued that it would mean the eviction of all the most needy slum-dwellers. In this he was proved quite right. Only eleven finally became rehoused in the spanking new Boundary, as Sarah Wise’s eloquent study ‘The Blackest Streets’ documents. But for all that, it is a fitting legacy since Arnold had espoused so many of the causes that led to the development of social housing in Britain.

Arthur Arnold (1833-1902)

Arthur Arnold (1833-1902)

He himself had been born on May 28th 1833 to a respectable Kent family, and grew up with two brothers and three sisters in Gravesend. Unlike his older brother Edwin (born in 1832), he had no formal education since he was an ailing child. But he trained as a land agent and surveyor, moving naturally into the whole area of civic improvement that was so powerful a movement at that time.

From the start Arnold was a staunch radical. His paper, The Echo, campaigned for universal suffrage, for state ownership of the railways, Home Rule for Ireland and the disestablishment of the Church. Arnold himself had a gift for recognising young talent and hired and nurtured a number of writers who later became key journalists and editors themselves. With his wife, Amelia – daughter of the Governor of Sierra Leone – he was part of the anti-alcohol/temperance movement. When, after seven years, the paper was sold, he sought a seat in Parliament, and was finally successful in 1880 when he was elected MP for Salford.

His time in Parliament lasted five years. When he lost his seat, he turned his energies to London politics, to the new LCC and the road that led to Arnold Circus. Years of public service and a knighthood followed, with his last public engagement just a few weeks before his death of a heart attack on May 20th, 1902.

Edwin Arnold (1832-1904)

But influential as he was, it is nevertheless true that his older brother was more of a household name at the time. Edwin’s story is surprising too. Unlike Arthur, Edwin had been a brilliant scholar. From childhood up, he had won every prize going, and gone on to study at King’s College, London and then University College, Oxford, producing a poem that won the coveted Newdigate Prize.

For a short time, he taught English in Birmingham, but provincial schoolmastering was not his forte. A friend helped him gain the headship of the Deccan College in Poona/Pune and so in 1857 he set sail, with his wife and young son, for India, where he lived for four years. They were seminal years. Edwin was not an imperialist who kept himself secluded in the British enclave or cantonment. He learnt the local language, Marathi, as well as Sanskrit and Persian. He travelled, and engaged with local intellectuals: he mentored the poet Iqbal, who was a founding voice for the creation of Pakistan. And – most significantly – he made contact with Buddhism, which many years later was to lead to his fame.

But before that could occur, thirty years or so of journalism took place. Returning to England, he joined the Daily Telegraph, and was its Chief Editor for sixteen years, from 1873. It was a glorious time for the paper. It acquired such a dynamic and radical edge that the paper, that had been merely one of Fleet Street’s lesser dailies, was elevated to being the only rival to the previously unrivalled Times. Edwin Arnold himself was responsible for a number of bold commissions, amongst them sending Stanley to Africa to see if he could find the missing explorer, David Livingstone.

And then, in 1879, his life changed. He had been writing a long poem off and on, composing it, he said modestly ‘in my spare moments, being jotted down on anything that was available’. A life of the Buddha in blank verse and stretching to fifty thousand words, ‘The Light of Asia’ opened the eyes of the west to Buddhism and found its way into a huge amount of Victorian households, It was a runaway success. It went into sixty editions in Britain and even more in America where it was even dramatised on Broadway. It was turned into an opera with an Italian libretto too and performed in Paris in 1892, where George Bernard Shaw saw it and gave it a good review.

The book made him a rich man. It also earned him the Order of the White Elephant, awarded by a grateful King of Siam for ‘having made a European Buddhist speak beautifully in the most widespread language in the world.’ This award, interestingly, neatly matched his brother Arthur’s: for he had been awarded the Golden Cross of the Saviour by the King of Greece for his own sympathetic writings drawing on his travels in the Levant.

The two brothers – so alike in their vitality and determination – were born within a year of each other and died within two years of each other. Arthur and his wife, Amelia (a writer of feminist novels and eleven years his senior) had no children. Edwin on the other hand had three wives, with the first two dying before him. He married his final wife, a young Japanese woman of twenty, after meeting her in his travels through Japan.

In the year in which the Arnold Circus bandstand reaches one hundred years old, it is fitting to remember and mark not only Arthur, but also the brother to whom he was so close, for their idealism, staying power and open-minded curiosity. These are lasting values with lasting value.

Article copyright © The Friends of Arnold Circus