Spitalfields Antiques Market 20

This is Debbie Price with her two fine daughters Tilly & Scarlett. “They don’t get pocket money, they have to sell things to earn their own money,” explained Debbie – a seasoned trader who began going to jumble sales at the age of ten and reselling her finds, just as she is now teaching her daughters to do. It means that while Tilly is awaiting her exam results this week, her ever-loving mother can be reassured that even if she does not get the grades, her daughter has something to fall back on. Like mother, like daughters.

This is Susan Hustwayte holding a Truman’s ashtray, a trophy of the brewery where she once worked as secretary to Mr Perkins, earning a wage of seven pounds and sixpence that she spent on fashions in Petticoat Lane each week. Susan comes from a venerable family whose ancestors include Henry VIII’s gardener and inherits her addiction to markets and collectibles from her father. “He was a demolition contractor who took me scavenging on sites when I was five years old,” she recalled with a smirk, “You should have seen his bedroom – it looked like Steptoe’s backyard!” Like father, like daughter.

This is Catherine with her daughter Sarah, and noble boyfriend Gary who carries the boxes. “All my family are in markets, one way or another,” declared Catherine plainly, a veteran of fifteen years of car boot sales,“My parents started off with a stall and I worked for them as a little girl.” Now Sarah has started trading too, showing her mother some moral support, “I’ve been helping my mum for years and I decided to give up my office job and go independent selling clothes,” she admitted shyly. Like mother and boyfriend, like daughter.

This is glass dealer Sarah Ovans‘ son John Ovans, who with knitwear designer Morgan Allen-Oliver also deals in glass. “Sarah’s house is like a showroom with all this glass everywhere, priced for sale,” revealed Morgan with a coy grin. “Her taste is sophisticated and grown up, whereas our stall is like a sweetshop!” he added, exchanging a knowing smile with John as they happily gestured in unison at their multi-coloured glittering display. Like mother, like son and boyfriend.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Blackberry season in the East End

It is blackberry season. In Spitalfields, I always feel a pang to be reminded of the seasonal delights that I am missing here in the midst of the city. When I was a child, I thought the chief virtue of growing up was the opportunity to reach blackberries that grew higher in the hedgerow. I spent so many seasons trailing behind my parents on blackberry picking expeditions down deep lanes and along the banks of the river Exe, carrying baskets and plastic bags – and armed with umbrellas or walking sticks to pull down elusive branches from above. It was an exciting yet risky endeavour, if you were to avoid getting scratched by thorns or stung by nettles, but we were prepared to endure these petty hazards for the sake of blackberry jam to enjoy in the Winter months ahead.

As a consequence, even today I feel that a Summer without picking blackberries is incomplete and so, in order to exercise my ability to reach those higher branches, I set out to find some blackberries in the East End. I took a bus to Bow and got off at the church, walking through the streets until I came to Three Mills Island. Just fifty yards along the towpath of the river Lee, I found blackberries growing in profusion, cascading from the old walls of abandoned factories and set to work picking them, pulling down those top branches that are especially heavy with fruit. Within minutes, a mother and her two children who had been similarly occupied came past clutching their bags of blackberries and, without a second thought, we exchanged greetings. It was the natural camaraderie of purple-fingered blackberry pickers.

At the end of August, the variety of Autumn berries was already diverse, scarlet rosehips, shiny black elderberries, delicately segmented pink spindleberries, red hawthorn berries, purple sloes and even golden greengages. I lost sense of time absorbed in picking blackberries, making my slow deliberate progress along the hedge. The quiet river was covered in green pondweed where moorhens made aimless trails, and I stood to watch the lonely heron in contemplation, until it gave flight when a District Line train rattled over the bridge towards central London. I followed the towpath North, aware that I was walking a narrow passage of green between the new housing developments of Hackney Wick on one bank of the river and the Olympic site on the other. High winds sent clouds racing across the sky and the sunshine I had been granted for my blackberrying expedition was shortlived, turning to rain before I reached Bethnal Green.

In Spitalfields, I tipped my modest haul of blackberries into an old bowl. Gleaming berries that come for free and incarnate all the poetry of late Summer in England. I was satisfied that the annual ritual had been observed. It was the joyful culmination of Summer. My passion for blackberry picking is sated for another year and there will be blackberry crumble tonight. Within weeks, the flies will get to the bushes and blackberries can no longer be picked. Each year presents this momentary opportunity, once they become ripe and before they are ruined – weather permitting. You are given one chance to pick blackberries before Summer is over. It is a chance which, for someone like myself, ever eager to seize the ephemeral pleasures of existence, cannot be missed.

The House Mill at Three Mills Island, a tidal mill built on the River Lee in 1776.

At Malplaquet House

Walking East from Spitalfields down the Mile End Rd, I arrived at the gateway surmounted by two stone eagles, and reached through the iron gate to pull on a tenuous bell cord, before casting my eyes up at Malplaquet House. Hovering nervously on the dusty pavement with the traffic roaring around my ears, I looked through the railings into the overgrown garden and beyond to the dark windows enclosing the secrets of this majestic four storey mansion (completed in 1742 by Thomas Andrews). Here I recognised a moment of anticipation comparable to that experienced by Pip, standing at the gate of Satis House before being admitted to meet Miss Havisham. Let me admit, for years I have paused to peek through the railings, but I never had the courage to ring the bell at Malplaquet House before.

Ushered through the gate, up the garden path and through the door, I was not disappointed to enter the hallway that I had dreamed of, discovering it thickly lined with stags’ heads, reliefs, and antiquarian fragments, including a cast of the hieroglyphic inscription from between the front paws of the sphinx. Here my bright-eyed host, Tim Knox, director of Sir John Soane’s Museum, introduced me to landscape gardener Todd Longstaffe-Gowan with whom he restored the house. In 1998, when they bought Malplaquet House from the Spitalfields Trust, the edifice had not been inhabited in over a century, and there were two shops,“F.W. Woodruff & Co Ltd, Printers Engineers” and “Instant Typewriter Repairs,” extending through the current front garden to the street.

Yet this pair of single-minded fellows recklessly embraced the opportunity of living in a building site for the next five years, repairing the ancient fabric, removing modern accretions and tactfully reinstating missing elements – all for the sake of bringing one of London’s long forgotten mansions back. Today their interventions are barely apparent, and when Tim led me into his Regency dining room, as created in the seventeen nineties by the brewer Henry Charrington and painted an appetising arsenic green, I found it difficult to believe this had once been a typewriter repair shop. Everywhere, original paintwork and worn surfaces have been preserved, idiosyncratic details and textures which record the passage of people through the house and ensure the soul of the place lingers on. The sum total of the restoration is that every space feels natural, as you walk from one room to another, each has its own identity and proportion, as if it always was like this.

By December 1999, the shops had been almost entirely removed leaving just the facades standing on the street, concealing the garden which had already been planted and the front wall of the house which was repaired, with windows and front door in place. Then, on Christmas Eve an exceptionally powerful wind blew down the Mile End Rd, and Tim woke in the night to an almighty “bang”, only to discover that in a transformation worthy of pantomime, some passing yuletide spirit had thrown the shopfronts down into the street to reveal Malplaquet House restored. It was a suitably dramatic coup, because today the house more than lives up to its spectacular debut – it is some kind of masterpiece.

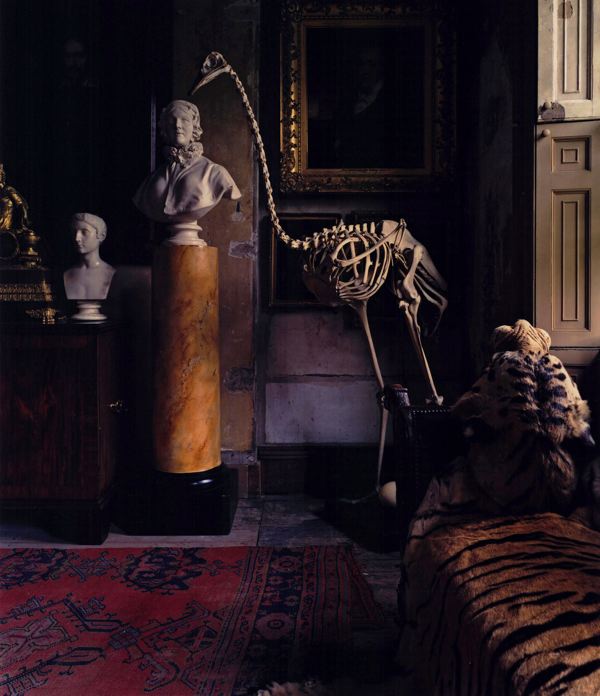

I hope Tim will forgive me if I confess that while he outlined the engaging history of the house with professional eloquence – as we sipped tea in the first floor drawing-room – my eyes wandered to the mountain goat under the table eyeing me suspiciously. Similarly, in the drawing-room, my attention strayed from the finer points of the architectural detail towards the ostrich skeleton in the corner.

As even a cursory glance at the photos will reveal, Tim & Todd are ferocious collectors, a compulsion that can be traced back to childhoods spent in Fiji and the West Indies. They have delighted in the opportunities Malplaquet House provides to display and expand their vast collection of ethnographic, historical, architectural and religious artefacts, natural history specimens and old master paintings. Consequently, as Tim kindly led me from one room to another, up and down stairs, through closets, opening cupboards in passing, directing my gaze this way and that, while continuously explaining the renovation, pointing out the features and giving historical context, I could do little but nod and exclaim in superlatives that grew increasingly feeble in the face of the overwhelming phantasmagoric detail of the collection.

In fact, the collection has outgrown the house and the startling news I have to impart is that after twelve years, the owners now seek a larger home for their acquisitions, out of London. Gazing from an upper window and turning his back on the collection, Tim explained how fascinated he is by the everyday life of the Mile End Rd and the taxi office across the road that has remained open night and day since he first came to live here. Next, we walked into the walled yard at the rear, canopied by three-hundred-year-old tree ferns, and wondered at the echoing sound of a large community of sparrows that have made their home in this green oasis. It is a curious paradox of submitting to the spell of this remarkable house that the ordinary world becomes exotic by comparison.

I have been in older houses and grander houses, but Malplaquet House has something beyond history and style, it has pervasive atmosphere. It has mystery. It has romance. You could get lost in there. When I came to leave, I shook hands with Tim and lingered, reluctant to move, because Malplaquet House held me spellbound. After my hour’s visit, I did not want to leave, so Tim walked with me through the garden into the street to say farewell, in a private rehearsal for his own departure from Malplaquet House one day.

The basement kitchen (photo by Klaus Wehner)

(photo by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan)

The North-west bedroom (photo by Klaus Wehner)

The South-east bedroom (photo by Derek Henderson)

(photo by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan)

(photo by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan)

(photo by Derek Henderson)

Looking out from the first floor window to the Mile End Rd. (photo by Andrew Lawson)

Malplaquet House, May 2010 (photo by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan)

Malplaquet House, May 1998 (photo by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan)

The photo of the ostrich in the dining room is by Derek Henderson

The rise of Ben Eine, street artist

“It’s been mad!” announced Ben Eine, with a jubilant cock-eyed grin, when I walked over to visit him at work on a new painting in Middlesex St recently. Since I was there in June to record the origin of his project – masterminded by Jessica Tibbles of the Electric Blue Gallery – to paint the complete alphabet on the shutters of the shops, there have been significant developments. Not only did Ben complete the alphabet and the glorious “Happy” painting above, but he also achieved overnight international fame when David Cameron gave his painting “Twenty-first Century City” to Barack Obama as a gift. Now that he is the only British painter to have a picture hanging in the White House, the shopkeepers of Middlesex St are feeling justifiably proud of their foresight in permitting Ben to paint their shutters this Summer.

“For the first time in my life, I am making my living as an artist,” admitted Ben, his eyes gleaming in triumph, revealing the primary outcome of this absurd event which has transformed his reputation from that of a highly respected figure (within the confines of street art) into a household name. In the past, he worked making screenprints for others and it is even rumoured that he was the one employed to do the paintings for Banksy – but now Ben Eine is a star in his own right. And, when I arrived to shake his hand last week, there were three eager photographers and a cameraman following Ben’s every move as he undertook an ambitious mural over successive Saturdays on a wall at the Liverpool St end of Middlesex St.

Once upon a time, Ben used to get arrested regularly and only began painting the letters of the alphabet on shutters, for which he always asks permission, when a judge warned him that another conviction for criminal damage would mean a prison sentence. Happily those days are behind him now, because as a family man of forty years old with three children, this is no longer a risk he can take. He told me, with incredulous delight, that a police car pulled up recently and the officers got out to ask for his autograph for their children.

Pulling a grimace of crazed disbelief, Ben admitted he has shaken hands with the Prime Minister, “I went to visit David Cameron. I rang the doorbell at number ten and they let me in ! I had to sit and wait while he spoke to Mervyn King and then we had a chat, before he went off to have dinner with Berlusconi.” Adding breezily, “He seemed a nice man,” with a non-committal grin, revealing he has never voted in his life. In the Hackney Rd, Ben has painted his vivid personal response to these events in six-foot high letters composed of smiley faces, spelling out “The Strangest Week.” – a work which, with supreme irony, Hackney Council are threatening to paint over imminently.

Down in Middlesex St, all the media attention received by Ben’s alphabet has empowered curator Jessica Tibbles to enlist other artists to paint shutters as the project spills into the adjoining streets. At this moment, Goulston St is currently acquiring a series of monochromatic images of the beasts that once roamed here when London was a prehistoric swamp. Meanwhile Jessica’s sights are set upon Wentworth St, aiming for a total of more than three hundred painted shutters, transforming this neglected neighbourhood into an after hours gallery of street art with Ben Eine’s alphabet as the centrepiece.

Ben’s current work-in-progess uses his trademark shadowed letters to spell phrases that will only be revealed in their legible entirety when the work is completed next Saturday. I watched for several hours as, working with two assistants, Ben painted a series of red squares upon a yellow ground, in an apparently haphazard fashion, moving back and forth across the surface with a spray can in one hand and cigarette in the other, hunching his shoulders a little and cocking his head as transfers his gaze between the detail he is working on and the larger scheme of things. “I haven’t got clue what I am doing,” he declared to me with the spontaneous swagger of an experienced showman, whilst pouring himself a Jack Daniels and coke in a plastic cup, against the chill of the damp afternoon.

The very nature of this work, in which each red square corresponds to a letter spelling out the undisclosed text reveals a grand design that Ben is fully aware of. He cultivates an appealingly ego-free happy-go-lucky manner that denies his own sophistication. Yet after he went off for a break and the rain set in, there was a brightly coloured backpack left on the pavement and I realised it was Ben’s. He left it in assumption of an unspoken trust that we would take care of it for him. There is a certain touching vulnerability about this man who gleefully leaps up unstable ladders in the rain, leaning too far out with his spray can while puffing on a cigarette.

While the conception of Ben’s work is always sharp, there is an innate roughness to his work on the street, always designed to be seen from a distance and while the spectator is in motion. I noticed that some of the letters of the alphabet in Middlesex St were already peeling and usage will damage them further. Part of the mutable world of the street, Ben has accepted the ephemeral nature of his work long ago, fleeting like memories. If you go along to Middlesex St next Saturday you can experience the moment when the latest bright new work is revealed. Take the time to look for yourself, because none of these paintings will be here forever, they are the product of a moment, but – as a result of recent events – this moment belongs to Ben Eine.

You can read my earlier story The return of Ben Eine, street artist

At the North corner of the junction of Wentworth St and Middlesex St.

Looking down Middlesex St.

At the South corner of the junction of Wentworth St and Middlesex St.

Looking up Middlesex St.

Ben Eine’s “The strangest week” in the Hackney Rd.

Off the Hackney Rd.

Ben at work with an assistant in Middlesex St on Saturday August 14th.

Ben choosing the stencils for the individual letters.

Work-in-progress, pictured a week later.

The completed painting.

Columbia Road Market 49

This surreal conical-shaped flower emerging into the sunlight from the deep shadow of a late Summer’s afternoon is Hydrangea, Peniculata Limelight that I bought at Columbia Rd for just four pounds. My garden is too tiny for most hydrangeas but this small variety suits it well, and is especially welcome at this season when the yard is bereft of other flowers. The saving grace has been this rambling rose, Aimée Vibert, a pale noisette cultivated in 1828, that I planted two years ago and which, although it has already climbed to the window of my first floor drawing-room, has only just flowered for the very first time this week – offering just three sprays of fragrant double blooms up to the glass as if seeking approval. I love the form of these sprays, giving forth a cascade of roses all at once and I am especially delighted that it should come into bloom now at the end of August when most other roses are over. Henceforward I shall be able to anticipate the flowering of Aimée Vibert each year, as the last rose of Summer in Spitalfields.

Andy Rider, Rector of Spitalfields

This is Andy Rider sitting peacefully under the Mulberry tree with Archie, his golden retriever, in the garden of his eighteenth century rectory in the shadow of Christ Church, Spitalfields. I was delighted to have the opportunity of tea with Andy at the rectory one afternoon at three o’clock, because, as the one who has been given the “cure of souls” in this parish, he is the man with professional responsibility for my soul. Yet, although Christ Church is one of London’s grandest churches, Andy’s style is a little more relaxed, as signified by the blue jeans in the picture above and the huge dog basket almost filling the hallway, which is the first thing you see when you step through the door of the magnificent rectory.

“People ask if it makes me feel small, living here,” he declared, as we strolled through the elegantly proportioned rooms, which seemed a strange question to me since Andy is a tall man, distinguished by a certain physical confidence revealing he is comfortable in his own body and at home in his rectory too. I suppose I had not expected someone whose primary concern is with spiritual life to be so present in the material world, possessive of a strong handshake, an easy smile and a clear blue-eyed gaze. Taking his London A-Z from the shelf, Andy outlined the geography of the parish and listed the various services that he presides over each week, describing the particulars of his employment in exercising the “cure of souls” in Spitalfields.

Andy’s explanation of the tangible nature of his job made me realise that it was the intangible that I was interested in. “I chose to walk away from the church for ten years,” he admitted, lowering his voice,“but then through a series of events and co-incidences I found answers to the big questions, ‘Who am I? What is life about?’ and ‘Does God exist?’ These were answers that I accepted within my heart, in the knowledge that God is divine and He rose from the dead. And when I was nineteen, about seven months after that experience I found God calling me to become a full-time minister.”

Baffled by this statement, I asked, “Are you talking literally?” “Yes,” he replied at once, speaking openly, without a glimmer of uncertainty, “I actually heard God speak to me. I was camping in Devon with a group of young people from the church. It was late in the evening and I went out to check the guy ropes of the tent in the dark. I was standing alone looking across the fields and marvelling at God’s creation, and then it was as if somebody was speaking and I remember looking around to see if anyone was there. It was a voice quite unlike a human voice, neither a woman nor a man. In the scriptures, the prophets describe God speaking as being like ‘the sound of many waters’ and that was how it sounded to me.” Then Andy looked at me with a shy smile, momentarily self-conscious, before clutching his hands to his head and confessing, “I can’t remember what He said exactly!’

My thoughts were racing in astonishment. Just minutes earlier, he had been searching his A-Z and we were discussing the new ipad, but now our conversation had entered another realm, yet a realm which for Andy carries equal reality. I do not know why I found his testimony shocking or why I was surprised to hear a priest tell me he believed in God. It appears that my personal perception of religion as moral belief, rather than as acceptance of supernatural events misses something fundamental – while for Andy this distinction does not exist. Returning to the bible, he described how the apostles were offered “a glimpse of glory,” a phrase that he applies to his own revelation too. “Most of us don’t look further,” he suggested regretfully, spreading his hands and explaining that he sees the modern day in direct continuum with the biblical world, in which God’s wonders are literally manifest and miracles are possible. “I haven’t seen an angel,” he added with a tinge of disappointment, yet with the undeniable implication that it could happen at any time.

Andy possesses a light touch, talking open-heartedly about big subjects without being borne down by them, while I was perplexed by his declaration. Yet I appreciate it is in the nature of faith to be inexplicable, and so I did not wish pursue my enquiry disingenuously, challenging what is sacred to him with casual scepticism. The world was still the same world to me, except now I knew that Andy embodies his role as rector, not just as the caretaker of a building but as a man with faith in the divine, inhabiting a spiritual universe that defies reason. I do not entirely accept the language of rational science myself, though I cannot make the leap of faith which religion requires either. God has not spoken to me yet. I must admit that as I listened to Andy describing his strange revelation, I envied the consolation that his belief has granted him just as I also know that such credulity is beyond me. Let me say, I was amazed to meet a man who believed in angels.

At Three Colts Lane

Situated midway between Spitalfields and Bethnal Green lies Three Colts Lane. Although many years have passed since there were colts here, today there are many other attractions to make this a compelling destination, especially if you are having problems with your car – because Three Colts Lane is where all the motor repair garages are to be found, gathered together in dozens and snuggled up close together in ramshackle order. Who can say how many repair shops there are in Three Colts Lane, since they inhabit the railway arches in the manner of interconnected troglodyte dwellings carved into a mountain, meaning no-one can ever tell where one garage begins and another ends.

Three Colts Lane is where the lines from the East and the North converge as they approach Liverpool St Station, providing a deep warren of vaulted spaces, extended by shambolic tin shacks and bordered with scruffy yards fenced off with corrugated iron. Here in this forgotten niche, while more fences and signs are added, few have ever been removed, creating a dense visual patchwork to fascinate the eye. Yet even before I arrived in Three Colts Lane, the commingled scents of engine oil and spray paint were drawing me closer with their intoxicating fragrance, because, although I have no car, I love to come here to explore this distinct corner of the East End that is a world of its own.

Each body shop presents a cavernous entrance, from which the sounds of banging and clanging and shouting emanate, every one attended by the employees, distinguished by their boiler suits and oily hands, happily enjoying cigarettes in the sun. Yet standing in the daylight and peering into the gloom, it is impossible to discern the relative size and shape of these garages that all appear to recede infinitely into the darkness beneath the railway arches. An investigation was necessary, and so I invited Sarah Ainslie, Spitalfields Life contributing photographer, to join me in my quest to explore this mysterious parallel universe that goes by the name of Three Colts Lane. And many delights awaited us, because at each garage we were welcomed by the mechanics, eager to have their pictures taken and show us the manifold splendours of their manor.

There is a cheerful spirit of anarchy that presides in Three Colts Lane, incarnated by the senior mechanic with his upper body under a taxicab, who, when we asked gingerly if we might take pictures of the extravagantly vaulted narrow old repair shop deep beneath the arches, declared,“It’s not my garage. Do as you please! Make yourself at home!” To outsiders, these dark grimy spaces might appear alien, but to those who work here it is a zone where everyone knows everyone else, and where you can spend your working life in a society with its own codes, hierarchy and respect – only encountering the outside world through the motorists and cabbies that arrive needing repairs. My father was a mechanic, and I recognise the liberation of filth, how being dirty in your work sets you apart from others’ expectations. The layers of grime and dirt here – in an environment comprised almost exclusively of small businesses where no-one wears a white collar – speak eloquently of a place that is a law unto itself.

Starting at the Eastern end of Three Colts Lane, the first person we met was Lofty, proprietor of the A1 Car Centre, who proved to be a gracious ambassador for the territory. “Some garages, they just want to take the money,” Lofty declared in wonder, his chestnut-brown eyes glinting with righteous ire at the injustice – like a sheriff denouncing outlaws – before he pledged his own personal doctrine of decency, “But I believe it’s how you treat the customers that’s the most important thing, that’s why we are still here after twenty-five years.” And proof that Lofty is as good as his word was evident recently when seven hundred customers signed a petition saving the garage from developers who threatened to build student housing on the site.

We crossed the road to shake hands with Nicky at the Coborn Garage, admiring the fresh and gaudy patriotic colour scheme of red, white and blue, and his decorative signwriting that would not be out-of-place on a gipsy caravan. Under the railway bridge and down the road, we encountered Erdal and his nephew at Repairs R Us, where we marvelled at the monster engine from a Volvo truck that Erdal rebuilt and today keeps as a trophy by the entrance of his tiny arch. Further down, we met Ahmed, a native of Cyprus who grew up above the synagogue in Heneage St and has run his garage here for twenty-eight years. At the corner, across from Bethnal Green Station, we were greeted by Ian & Trevor, two softly spoken brothers who have been here twenty years repairing taxis in a former a scrap yard, still retaining its old weighbridge. We all squinted together at the drain pipe head dated 1870 with the initials of the Great Eastern Railway upon it, declaring the history of the site in gothic capitals, before Ian extracted a promise from me to come back once I had discovered the origin of the name Three Colts Lane.

Apart from calendar girls adorning the walls, the only women we glimpsed were those who restricted themselves to answering the telephone – barely visible in tiny cabins of domestic comfort, sheltering their femininity against the barbaric male chaos of the machine shops. But then, strolling down a back lane and passing one of the governors in a heated altercation with a quivering cabbie who had innocently scraped his Daimler, thereby providing the catalyst for an arresting display of bullish masculinity, we encountered Ilfet. With a triumphant mixture of self-assurance and sharp humour, Ilfet has won the respect of her male colleagues in the body shop, wielding a spanner as well as the next man. A bold pioneer in her field and stirling example to others, I was proud to shake the hand of Ilfet, the only – or rather – the first female mechanic in Three Colts Lane.

Growing bolder, we ventured deeper to discover the paint shops and frames where taxis were hoisted up for major surgery. We left daylight behind us to explore the furthest recesses of the dripping vaults, lined with corrugated iron, where a fluorescent glow pervaded the scene of lurid-coloured motors crouching in the gloom. We had arrived at the heart of Three Colts Lane, vibrating to the diabolic roar of the high speed trains passing overhead, whisking passengers in and out of London, oblivious to the hidden world beneath the tracks.

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie