Dan Jones’ East End Portraits

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

In recent years, Dan Jones has painted a magnificent series from different eras for his EAST END PORTRAITS. Many of these are well known but others less familiar, so you can click on any of the names to learn more about the subjects.

Police Constable James Stewart

Portraits copyright © Dan Jones

You may also like to take a look at

So Long, Terry O’ Leary

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

Terry O’Leary died on 31st July aged sixty-four

Terry O’Leary 1960-2024

“For two years, I cared for my brother – who was diagnosed with HIV in 1987 – in his council flat, but after he died I couldn’t stay there because my relationship with him as his sister wasn’t recognised by the council, and that’s how I became homeless,” said Terry, speaking plainly yet without self-pity, as we sat on either side of a table in Dino’s Cafe, Spitalfields. And there, in a single sentence I learnt the explanation of how one woman, in spite of her intelligence and skill, fell through the surface of the world and found herself living in a hostel with one hundred and twenty-eight other homeless people.

Terry was a shrewd woman with an innate dignity and a lightness of manner too. She managed to be both vividly present in the moment and also detached – considering and assessing – though quick to smile at the ironies of life. She wore utilitarian clothing which revealed little of the wearer and sometimes she presented an apparently tentative presence, but when you met her sympathetic dark eyes, she revealed her strength and her capacity for joy.

No one could deny it was an act of moral courage, when Terry gave up her career as a chef to care for her brother at a time when little support or medication was available to those with AIDS, moving in with him and devoting herself fully to his care. Yet in spite of the cruel outcome of her sacrifice, Terry discovered the resourcefulness to create another existence, which allowed her to draw upon these experiences in a creative way, through her work as performer and teacher with Cardboard Citizens, the homeless people’s theatre company based in Spitalfields.

“I took what I could with me, the rest I left behind. I took photographs and personal things. You fill your car with your TV, records, books and all the rest of it – but then you find it can be quite liberating because you realise all that stuff is not important,” admitted Terry with a wry smile, recounting a lesson born out of necessity. In the Mare St hostel in Hackney, Terry stayed in her tiny room to avoid the culture of alcohol and drug-taking that prevailed, but instead she found herself at the mercy of the absurdly doctrinaire bureaucracy, “I remember the staff coming round and saying, ‘You have to remove one of the two chairs in your room because you’re only allowed to have one.'” Terry recalled, “You find you’re living in a universe where you can get evicted for having two chairs in your room,” she added with a tragic grin.

A few months after she came to the hostel, Cardboard Citizens visited to perform and stage workshops, permitting Terry to participate and make some friends – but most importantly granting her a new role in life. “I was hooked,” confided Terry, “What I liked about it was the opportunity to talk about our own experiences and how we can make a change. And the best part of it was when the audience became involved and got on stage.” Terry joined the company and described their aim to me as being to “give voice to the homeless oppressed and show the situations homeless people face.”

Inspired by the principles of theatrical visionary Augusto Boal, the company perform in homeless shelters and hostels, creating vital performances that invite audiences of the homeless to participate, addressing in drama the pertinent questions and challenges they face in life – all in pursuit of the possibility of change.

Terry’s role was central to the company, as mediator, bringing the audience to the play, and raising questions that articulated the discussion manifest in the drama. She carried it off with grace, becoming the moral centre of the performance. And it was a natural role for Terry, one she referred to as “Joker” – somebody who will always challenge – anchoring the evening with her sense of levity and quick intelligence, without ever admitting that she understood more than her audience. Though, knowing Terry’s story, I found it especially poignant to observe Terry’s measured equanimity, even when the drama dealt with issues of grief and dislocation that are familiar territory for her personally.

“You don’t have to accept things as they are. You can fight back,” declared Terry, her dark eyes glinting as she spoke from first hand experience, when I asked how her understanding of life had been altered by becoming homeless. “Why is it that the economic underclass are being hammered for the mess that we’re in?” she asked in furious indignation, “I think what’s opened my eyes is that there’s so much kindness and support coming from people who have got very little. I can’t deal with the big picture, I tend to narrow it down to the people in the room and just keep chipping away at small changes. And I’m going to do this for the rest of my life.” There was an unsentimental fire in Terry’s rhetoric, denoting someone who had been granted a hard won clarity of vision, and at the Code St hostel where I saw the performance I was touched to see her exchanging greetings with long-term homeless people she had known over the years she had worked with Cardboard Citizens.

As we left Dino’s Cafe and walked up the steps of Christ Church, Spitalfields, to take Terry’s portrait in the Winter sunlight, she cast her eyes around in wonder at the everyday spectacle of people walking to and fro, and confessed to me, “I teach up at Central School of Speech & Drama now and it’s quite amazing to think ten years ago I was sitting in a hostel, wondering what’s going to happen next and what’s my future going to be? Am I going to be like that woman down the hall, drunk off her head, or on crack?” Then she it shrugged off as she turned to the camera.

Terry thought often about her brother. “His eyesight started to go and he set fire to the bed,” she told me, explaining why it became imperative to move in with him, “He was a stubborn guy but he had to concede that he needed help. He was developing dementia and his eyesight was fading.” It was his unexpected illness and death that triggered the big changes in her existence, and afterwards Terry found herself at the centre of a whole new life.

Terry when she started with Cardboard Citizens in 2002.

“Terry worked for Cardboard Citizens after finding us first in the late nineties in the hostel in Mare St, an old police section house, where she was living and where we were first based. As she never tired of telling, she participated in a workshop I led in the old gym in the basement of the hostel, and was as mischievous on that first encounter as ever after, refusing to come down from one of those hanging ropes, and generally disrupting, in a most creative way. She was an actor for us for some years, then graduated to the role of Joker (facilitator/difficultator) and workshop leader, then Associate Director. She stepped down a couple of years back to care for her lifelong partner Kath Beach.”

Adrian Jackson, former Director of Cardboard Citizens

Charles Jones, Photographer & Gardener

Tickets are available for my tour throughout August & September

Garden scene with photographer’s cloth backdrop c.1900

These beautiful photographs are all that exist to speak of the life of Charles Jones. Very little is known of the events and tenor of his existence, and even the survival of these pictures was left to chance, but now they ensure him posthumous status as one of the great plant photographers. When he died in Lincolnshire in 1959, aged 92, without claiming his pension for many years and in a house without running water or electricity, almost no-one was aware that he was a photographer. And he would be completely forgotten now, if not for the fortuitous discovery made twenty-two years later at Bermondsey Market, of a box of hundreds of his golden-toned gelatin silver prints made from glass plate negatives.

Born in 1866 in Wolverhampton, Jones was an exceptionally gifted professional gardener who worked upon several private estates, most notably Ote Hall near Burgess Hill in Sussex, where his talent received the attention of The Gardener’s Chronicle of 20th September 1905.

“The present gardener, Charles Jones, has had a large share in the modelling of the gardens as they now appear, for on all sides can be seen evidence of his work in the making of flowerbeds and borders and in the planting of fruit trees. Mr Jones is quite an enthusiastic fruit grower and his delight in his well-trained trees was readily apparent…. The lack of extensive glasshouses is no deterrent to Mr Jones in producing supplies of choice fruit and flowers… By the help of wind screens, he has converted warm nooks into suitable places for the growing of tender subjects and with the aid of a few unheated frames produces a goodly supply. Thus is the resourcefulness of the ingenious gardener who has not an unlimited supply of the best appurtenances seen.”

The mystery is how Jones produced such a huge body of photography and developed his distinctive aesthetic in complete isolation. The quality of the prints and notation suggests that he regarded himself as a serious photographer although there is no evidence that he ever published or exhibited his work. A sole advert in Popular Gardening exists offering to photograph people’s gardens for half a crown, suggesting wider ambitions, yet whether anyone took him up on the offer we do not know. Jones’ grandchildren recall that, in old age, he used his own glass plates as cloches to protect his seedlings against frost – which may explain why no negatives have survived.

There is a spare quality and an uncluttered aesthetic in Jones’ images that permits them to appear contemporary a hundred years after they were taken, while the intense focus upon the minutiae of these specimens reveals both Jones’ close knowledge of his own produce and his pride as a gardener in recording his creations. Charles Jones’ sensibility, delighting in the bounty of nature and the beauty of plant forms, and fascinated with variance in growth, is one that any gardener or cook will appreciate.

Swede Green Top

Bean Runner

Stokesia Cyanea

Turnip Green Globe

Bean Longpod

Potato Midlothian Early

Pea Rival

Onion Brown Globe

Cucumber Ridge

Mangold Yellow Globe

Bean (Dwarf) Ne Plus Ultra

Mangold Red Tankard

Seedpods on the head of a Standard Rose

Ornamental Gourd

Bean Runner

Apple Gateshead Codlin

Captain Hayward

Larry’s Perfection

Pear Beurré Diel

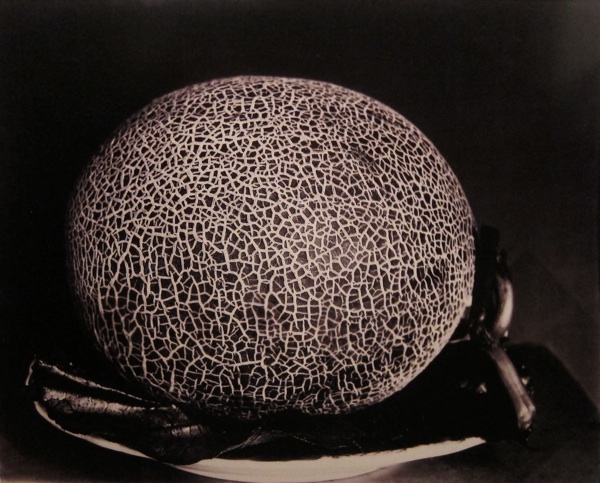

Melon Sutton’s Superlative

Mangold Green Top

Charles Harry Jones (1866-1959) c. 1904

The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones by Sean Sexton & Robert Flynn Johnson is published by Thames & Hudson

You might also like to read about

The Secret Gardens of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

Buying Vegetables for Leila’s Shop

Ted Vanner, Model Steam Boat Pioneer

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Ted with SS Star

This is the earliest photograph of Ted Vanner, taken when when he was twenty-six years old in 1909, cradling one of his cherished creations with barely-concealed pride. Born in 1883 in Deptford as the second of seven children, Ted began his working life as a blacksmith and apparently gained no formal training as an engineer yet became a legendary innovator in model boat design. An early member of Victoria Model Steamboat Club, founded in 1904, Ted remained prominent in the club for more than sixty years until his death in 1955 when his wife Daisy continued to race his boats in her nineties until her death in 1973.

In later life, Ted Vanner recalled that he, along with other Victoria Model Steamboat Club members, took part in the first ever Model Engineer Regatta at Wembley in 1908. They all met at the Club Boat House in Victoria Park at 5:30am where Mr Blaney was busy cooking eggs and bacon over an oil stove for breakfast, and set out for Wembley in a horsedrawn van carrying boats and owners, ‘stopping at a few hurdles on the way.’

Working with the most rudimentary tools, it was his skill working with sheet metal and tinplate that set Ted Vanner apart from other competitors. According to Boat Club President Norman Phelps, Ted started with a ‘buck’ made from orange boxes and plasterer’s laths, which he would ‘plate’ with sections of cocoa tins. In order to create a joint that could be soldered, each plate overlapped the previous one, starting from the stern and working forward. This was Ted’s method to create elegantly stream-lined hulls that enabled him to produce model boats which were faster than his rivals. The refined shapes were achieved by ‘stroking’ the tin over a flat iron before the plates were soldered together with a large iron, heated either in the living room fire or on a gas ring.

In spite of these primitive construction techniques, Ted became an ambitious innovator. The early boats he built were steam driven tugs, such as he would have seen in the London Docks, but he quickly graduated to speed boats with sophisticated multi-cylinder engines. Ted acquired a reputation, competing at regattas all around the country, carrying his boats on the train and representing Victoria Model Steamboat Club in Paris in 1927, winning first prize with Bon-Ami, second prize with Leda III and third prize with Ledaette.

Today, Victoria Model Steamboat Club is one of only a small handful of surviving model boat clubs but you may still see their vessels on the Victoria Park Boating Lake each Sunday in Summer. Many of the boats in the collection are now over a century old and, if you are lucky, you may even get to see one of Ted Vanner’s creations in action. Seven of his elegant craft remain in working order, carrying his reputation into the future. An inspirational creator, making so much out of so little with such astonishing ingenuity, Ted Vanner is an unsung hero and legend in the civilised world of model boat clubs.

Victoria Model Steamboat Club, 1909

Outside the Club House in Victoria Park

Boats inside the Club House

Ted releases Danube III

Ted is second from left

Ted releases Leda III

Ted stands on the right in this photo in Paris in 1927

Ted is fourth from the right in this line up at St Albans

On the Round Pond Kensington, 1954

Ted wins a trophy for Victoria Park Steamboat Club at Forest Gate Regatta, May 10th 1954

Presenting the prizes at the Victoria Park Model Steamboat Regatta, 1955

At this Model Boat club dinner, Ted & Daisy Vanner sit in the middle of the back row

Daisy Vanner in the fifties

Daisy and Ted on the left

In her nineties, Daisy Vanner continued to compete in regattas with Ted’s boats after his death

Leda III and All Alone, two of seven of Ted’s boats still in working order today

With thanks to Tim Westcott for supplying the photographs accompanying this feature

You may also like to read about

Norman Phelps, Boat Club President

Lucinda Douglas Menzies at Victoria Park Steam Model Boat Club

Michelle Attfield, Pointe Shoe Fitter

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

There is one woman, above all others, whom the world’s greatest ballerinas rely upon when it comes to fitting their shoes perfectly, Michelle Attfield of Freed of London. With generous spirit, self-effacing nature and fierce professionalism, Michelle is the queen of the pointe shoe and a legend in ballet circles.

In her half century at Freed, she has fitted ten-year-olds at the Royal Ballet School and accompanied them throughout the course of their careers, subtly modulating the design of their pointe shoes to accommodate both their physical change and the needs of their repertoire. “Sometimes I discover I know more than I think I do, when I look around for an expert and then realise that I have been around longer than anyone.” she admitted to me with a laugh of self-deprecation. In the volatile world of show business, Michelle is one of those rare figures whom dancers can always count upon for unwavering loyalty, appreciation and practical advice.

An ex-dancer and former customer of Freed, who was trained to fit shoes by Mrs Freed herself, Michelle embodies the spirit of the company that she has served all these years and which she delights to speak of. Yet she is the model of discretion, drawing a tactful curtain over the details of her intimate relationships with the great divas, and preferring to enthuse about show-business customers such as her beloved Patrick Swayze who visited Michelle at the shop after hours for extra fittings. “Supine with admiration,” is her verdict upon Mr Swayze.

“I’ve worked for Freed of London for forty-nine years, I’ve given my life to this company. I trained as a dancer but I wasn’t quite good enough to be a ballerina, so I qualified as a teacher and, since Freed’s shop in St Martin’s Lane were always advertising for staff in The Stage, I went along.

I was a Royal Academy of Dance student from the age of ten, so I had known Mrs Freed all that time. It was April and I had a teaching position starting in September, and when I told Mrs Freed she said ‘Why don’t you stay with us and stop all this nonsense?’ I said, ‘But I’ve got a job with the Royal Ballet.’ So I went to work at Freed permanently and never looked back. I tried to leave once when my daughter was born but, luckily for me, some of my customers refused to deal with anyone else. So they rang me and said, ‘You’ve got to come back.’

She was a monster. Mr Freed made shoes but Mrs Freed made the business. She was the dynamo. He was a shoemaker and a good one, she was a milliner. He did the making and she did the sewing. He invented the concept of making the shoe to fit the foot, prior to that they were very stylised, they propped you up but they didn’t let you dance. This development coincided with choreographers like Frederick Ashton and John Cranko wanting a little more and dancers who were willing to give a little more, and our shoes helped them to do it.

Mrs Freed visited the factory every day at seven-thirty and then she went and ran the shop all day – and she did that every day. I discovered the reason they always advertised in The Stage was because no-one could work for Mrs Freed. People exited from the shop very quickly, girls used to start in the morning and leave in the afternoon. I’d come back from lunch and ask ‘Where has she gone?’

Mr & Mrs Freed loved dancers but they didn’t want to go to the ballet. ‘No dear, you take the tickets and go to the ballet,’ they’d say to me, ‘we’ve had enough of that all day.’ You had to work uber-hard but I had been a dancer and dancers are used to hard work – class in the morning, rehearsal in the afternoon and performance in the evening. People either left at once or stayed forever, and it was the most wonderful place to work if you loved ballet – I fitted Margot Fonteyn!

I learnt to dance with one of the founder members of the Royal Academy of Dance and I learnt to fit shoes with Mrs Freed – the perfect foundation for this job. I try to be the bridge between the aspiration of the shoe and the reality of what can be achieved. Because Freed shoes are handmade, we can deliver exactly what an individual dancer needs and that’s why we have our reputation. A pointe shoe is a tool of the trade for a dancer, the shoe has to perform whatever she has to perform and, while a student may require longevity, a professional needs a show purposed for performance. The Freed pointe shoe is a chameleon because it will do anything for anyone.

I’ve fitted so many dancers that wherever I go in the world someone will come up and say, ‘Hello Michelle, I didn’t know you were going to be here.’ I’ve been all over to fit shoes, Japan, Australia, America, Milan, Verona, Paris – it goes on and on. But my greatest pleasure is what I regard as my ‘home companies,’ Royal Ballet, Birmingham Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, Scottish Ballet and Northern Ballet. I sit cross-legged on the floor and dancers come and stand in front of me, and I put shoes on them and decide which maker’s shoes would be best for them to wear. They chose the size but I choose the maker. It has to be a relationship of trust. I look at the whole dancer not just the feet. I say, ‘I know what you want and I’ll do it.’ You want the shoe to fit the dancer so well that you see the dancer not the shoe, you don’t want to see the shoe. And it’s a great feeling when you’ve got them where they want to be.

I think how lucky you are if you are involved with dance. Mine is a job that will never end because there will always be ballet. I used to take my daughter Sophie to the factory and she’d be crawling around on the floor getting dirty while I was picking up shoes. When she was eight, she stood in the wings when Nureyev was dancing, and she turned to me and asked ‘May I have a sandwich?’ She worked in the shop as a Saturday girl and Saturday in our shop is a baptism of fire. Then she went off to work in finance but after she got married, she asked to come back and now accompanies me when I do fittings. I’ve got to start handing over to her because I want to be like the Cheshire Cat, I want to disappear without people noticing me go.”

Michelle with Shevelle Dynott – “One of my darling boys…”

Michelle with Darcy Bussell.

Michelle with Agnes Oaks and Thomas Edur, joint directors of the Estonian National Ballet.

Michelle and fellow shoe fitters at the Freed shop in St Martin’s Lane in the eighties.

Frederick & Dora Freed in their shop.

Michelle in her dancing days.

Portrait of Michelle Attfield copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to read about

George Cruikshank’s London Summer

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

JULY 1838 – Flying Showers in Battersea Fields

Should you ever require it, here is evidence of the constant volatility of English summer weather, courtesy of George Cruikshank’s Comic Almanack published by Henry Tilt of Fleet St annually between 1835 & 1853, illustrating the festivals and seasons of the year for Londoners. (Click on any of these images to enlarge)

JUNE 1835 – At the Royal Academy

JUNE 1836 – Holidays at the Public Offices

JUNE 1837 – Haymaking

JULY 1835 – At Vauxhall Gardens

JULY 1836 – Dog Days in Houndsditch

JULY 1837 – Fancy Fair

AUGUST 1836 – Bathing at Brighton

AUGUST 1837 – Regatta

SEPTEMBER 1835 – Bartholomew Fair

SEPTEMBER 1837 – Cockney Sportsmen

You may also like to take a look at

Audrey Kneller Of Elder St

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Audrey on trip to Epping Forest, aged twelve in 1957

Audrey Kneller sent me this evocative memoir of her years in Elder St.

Elder St was not a pretty place in spite of its name. No buds burst forth each spring to awaken our spirits and no birds sang merrily to remind us of the wonders of nature. Instead soot lay unmolested in every crevice of the ancient brickwork, while the clanking and hissing of steam trains shunting reminded us of the presence of the large London terminus. Poverty was a mantle we refused to wear, but it lurked menacingly on every street corner.

Early in 1953, my Auntie Sophie happened to bump into Millie Berman, an old school friend of my mother’s. This chance meeting was to bring great changes. Millie lived with her daughter on the upper floors of a rented house in Elder St and was looking for someone to take over the tenancy as she was intending to move. Clearly this was an opportunity not be missed.

Shortly after the Coronation in June 1953, we left the comfort of our temporary home in Edgware and moved into the four-storey terraced house at 20 Elder St, Norton Folgate, E1. Our first impressions were far from favourable. The tallness of the houses and total absence of trees or even a blade of grass was very forbidding. However we gradually settled and discovered the bizarre fascinations of an urban existence.

At the back, towards Bishopsgate, there was a large bomb site where I joined some boys playing cowboys and indians, and had a lovely time amid the dirt and rubble. My mother, being a genteel person, was quite horrified when I returned home looking the worse for wear. Thereafter I played more civilised games with my sister and the other refined children of the neighbourhood inside the safe confines of the street. The bomb site, however, came into its own on Guy Fawkes Night when the sky was lit up with the flames of a huge bonfire and accompanying fireworks, watched by us from a third floor bedroom window.

Our part of Elder St was an ideal playground, not only because it sheltered us from traffic but also because of the numbers of children living in the surrounding houses and tenements, so we were seldom short of playmates. In those days, the threat of the motor car was almost non-existent, leaving us to play unrestricted and unhampered, a freedom children cannot enjoy today.

In fact, I cannot remember ever, in the early days of our life in Elder St, seeing a car impinge on our games of higher and higher, piggy in the middle and others too numerous to mention. We played in the road outside our door and no-one ever prevented us from chalking out our squares on the pavement for hopscotch. The black-painted iron bars above the basement in front of the some of the houses could easily be squeezed behind, if a side bar was missing, in order to retrieve a lost ball. These hump-shaped grills were nicknamed “airies,” and a cry would often go up, “It’s gone down the airy!” It was up to the smallest and bravest of us to crawl down into the tiny space below, and once down there you had an awful feeling of being trapped in a cage until you emerged triumphant with the lost ball.

I remember long summer evenings spent playing in the street and the man who came along on his three-wheeler, peddling ices. “Yum Yum” was the brand name and yum yum his ice lollies were, delicious and creamy. A good selling point was that every so often one of the lolly sticks would have the name “YUM YUM” printed on it and whoever had such a stick could have another lolly free on presenting it to the ice cream man. Once this fact became known, some of us sat in the gutter scratching the words “YUM YUM” on our spare sticks. But the ice cream man was not fooled and, some time later, when he came round again after an unexpectedly long interval, the name of the product had been changed to “WHIM”. The lollies were the same but somehow the gilt had gone from the gingerbread.

I recall with affection the Josephs family. Simon Josephs was my age and lived with his parents, two maiden aunts and an elderly grandmother around the corner in Fleur-de-Lis St. Their house was much smaller than ours and poorly built but they were a happy family. They even had a television set, which we did not have, and we lost no opportunity when invited to view. We also spent happy hours playing with Simon and his games, especially my favourite one of Monopoly.

Next door to the Josephs lived an elderly spinster and her bachelor brother who was disabled, having been afflicted with shell shock in the First World War, and I remember sitting with them one Yom Kippur evening waiting for the fast to end. One by one, the tiny houses and the dark overcrowded tenements in Fleur-de-Lis St became empty and boarded up awaiting demolition. The Josephs, we heard later, were re-housed in a new flat on the Ocean Estate in Mile End.

Number 26 Elder St was a tall narrow house accommodating two families, one Jewish and the one Gentile. My sister Yvonne and I would sometimes sit on the steps of the house playing gobs or five stones with the daughters of the respective families. Avril Levy from the Jewish family had a famous auntie, Adele Leigh a renowned opera singer, who would often call round, leaving her sporty two-seater Sunbeam Rapier outside the house.

In Blossom St lived a family that to me epitomised poverty both materially and spiritually. The children were neglected and ran around with bare feet and bare bottoms. I was very shocked because they were so different from us yet lived almost on our doorstep. One day, Christine, a little girl who lived at 16 Elder St, decided that we should venture into the house in Blossom St. We peered inside what seemed to be a dark hole with no semblance of what I considered to be the trappings of a home. Dirt and decay lay all around and I caught a glimpse of a man lying asleep on an old armchair which, instead of cushions, was covered with sacks filled with horse hair. Overcome by feelings of horror, disbelief and the foul stench that pervaded the building, we stepped backwards into the street, and quickly walked back to the welcome ‘civilisation’ of Elder St, never to set foot again in Blossom St.

As to the past history of our house, we were led to believe that it was built in the early eighteen-hundreds. I cannot support the validity of this but the house certainly contained some unusual features.

Looking through the windows at the back, high walls surrounded the yard which was no more than ten feet in depth, just enough space for a coal storage area and a washing line to be strung across. Our convenient position near Liverpool St Station could also be a disadvantage, if the wind was blowing in the wrong direction our clean laundry would be showered with a fine layer of soot.

Ours was the only house in Elder St – and for all we knew anywhere else in Norton Folgate – to have a bathroom. The fittings were brass and, instead of having a normal plughole, there was a tall brass post affair which had to be lifted up to let the water run away. Hot water came from an ancient geyser on the wall above the bath but woe betides anyone who fell foul of the delicate lighting-up procedure. I did once and was greeted with a loud bang. The secret was to run the water first and then ignite the gas. Henceforth, unless my mother or sister were there to do the honours, I felt it safer to spend my bath times in an old zinc tub in front of the fireplace in the living room.

Nevertheless, it was handy to have a bathroom, especially as a connecting door led into the back bedroom thereby giving us a bathroom en suite! The toilet was situated next to the bathroom on the first floor landing. To have an inside toilet was again untypical of the area, most toilets being situated outside in the backyard, as I found at our cousin’s house in Buxton St.

A house of this size required regular maintenance and my mother employed a spare-time handyman to keep the interior in a good state of repair. He came and went for six years, painting, papering, plumbing and fixing, and no sooner had he finished on the top floor than it was time to start again at the bottom, rather like the Forth Bridge.

An interesting feature of the house was a long speaking tube with a whistle at one end, extending from the top floor right down to the basement. Presumably a device once used by servants, this was a source of amusement. Another source of great amusement to us, as well as to other children in our street, was the wall panelling. We succeeded in convincing them that one on the first floor landing slid back to reveal a secret passageway, such as the ones used by Cavaliers to escape the Roundheads during the Civil War.

One day, my sister told some children playing in the street that there was something strange in our basement and they immediately came to investigate. Meanwhile, I had dressed up a tailor’s dummy in an old red frock and hid behind it. As the children descended the basement stairs, I slowly moved the dummy forward, calling out in an eerie voice. The inquisitive children scattered in haste, believing me to be a headless ghost!

Not long after we moved into Elder St, we discovered the presence of unwelcome lodgers lurking behind the skirting boards. After mousetraps failed to catch them, we acquired the services of a cat. One day, one of our cousins from Buxton St called round with a tabby who had the perfect markings of a tiger, so the name stuck. Tiger was a wonderfully docile pet but he lived up this name in keeping the rodent community at bay.

One day I found him sitting on the landing and tried to pick him to carry him downstairs but he would not budge. I could not understand it until my mother pointed out that he was standing guard over a small hole in the skirting board. We left him there all that day and eventually he returned to us of his own accord, presumably having accomplished his mission.

As to the other houses in Elder St, I am sure that none of us children had any idea of their historic value. As far as I could see, we were surrounded by decaying walls and we had to make the best of the situation until circumstances improved.

Although we may have been devoid of pastoral pleasures in Spitalfields, life was far from dull. We were living on the fringes of a great nucleus of Jewish enterprise and culture – consisting of delicatessens, bakeries, butcher shops and kosher restaurants, intermingled with other Jewish-owned businesses in the garment, jewellery and shoe trades, bookshops, a Yiddish theatre and numerous synagogues – stretching from Brick Lane southward to Houndsditch and eastward as far as Bow. This was our heritage, we had returned to the roots set down by our grandparents and thousands of other immigrants fifty years earlier.

Audrey’s tenth birthday tea in 1955

You may also like to read about