Colin O’Brien’s Clerkenwell Car Crashes

I am giving an illustrated lecture about Colin O’Brien, the Clerkenwell Photographer, on Tuesday 10th February at 6:30pm at Islington Museum, 245 St John St, EC1V 4NB. Entry is free and no booking is required, just come along.

Accident, daytime 1957

When Colin O’Brien (1940-2016) was growing up in Victoria Dwellings on the corner of Clerkenwell Rd and Faringdon Rd, there was a very unfortunate recurring problem which caused all the traffic lights at the junction to turn green at once. In the living room of the top floor flat where Colin lived with his parents, an ominous “crunch” would regularly be heard, occasioning the young photographer to lean out of the window with his box brownie camera and take the spectacular car crash photographs that you see here. Unaware of Weegee’s car crash photography in New York and predating Warhol’s fascination with the car crash as a photographic motif, Colin O’Brien’s car crash pictures are masterpieces in their own right.

Yet, even though they possess an extraordinary classically composed beauty, these photographs do not glamorise the tragedy of these violent random events – seen, as if from God’s eye view, they expose the hopeless pathos of the situation. And, half a century later, whilst we all agree that these accidents were profoundly unfortunate for those involved, I hope it is not in poor taste to say that, in terms of photography they represent a fortuitous collision of subject matter and nascent photographic talent. I say this because I believe that the first duty of any artist is to witness what is in front of you, and this remarkable collection of pictures which Colin took from his window – dating from the late forties when he got his first camera at the age of eight until the early sixties when the family moved out – is precisely that.

I accompanied Colin when he returned to the junction of the Clerkenwell Rd and Faringdon Rd in the hope of visiting the modern buildings upon the site of the former Victoria Dwellings. To our good fortune, once we explained the story, Tomasz, the superintendent of Herbal Hill Buildings, welcomed Colin as if he were one of current residents who had simply been away for the weekend. Magnanimously, he handed over the keys of the top flat on the corner – which, by a stroke of luck, was vacant – so that Colin might take pictures from the same vantage point as his original photographs.

We found a split-level, four bedroom penthouse apartment with breathtaking views towards the City, complete with statues, chandeliers and gold light switches. It was very different to the poor, three room flat Colin lived in with his parents where his mother hung a curtain over the gas meter. Yet here in this luxury dwelling, the melancholy of the empty rooms was inescapable, lined with tired beige carpet and haunted with ghost outlines of furniture that had been taken away. However, we had not come to view the property but to look out of the window and after Colin had opened three different ones, he settled upon the perspective that most closely correlated to his parents’ living room and leaned out.

“The Guinness ad is no longer there,” he commented – almost surprised – as if, somehow, he expected the reality of the nineteen fifties might somehow be restored. Apart from the blocks on the horizon, little had changed, though. The building on the opposite corner was the same then, the tube embankment and bridge were unaltered, the Booth’s Distillery building in Turnmills St still stood, as does the Clerkenwell Court House where Dickens once served as cub reporter. I left Colin to his photography as he became drawn into his lens, looking back into the midst of the last century and upon the urban landscape that contained the emotional history of his youth.

“It was the most exciting day of my life, when we left,” admitted Colin, with a fond grin of reminiscence, “Canvassers from the Labour Party used to come round asking for our votes and my father would ask them to build us better homes, and eventually they did. They built Michael Cliffe House, a tower block in Clerkenwell, and offered us the choice of any flat. My parents wanted one in the middle but I said, ‘No, let’s get the top flat!’ and I have it to this day. I took a photo of lightning over St Paul’s from there, and then I ran down to Fleet St and sold it to the Evening Standard.”

Colin O’Brien’s car crash photographs fascinate me with their intense, macabre beauty. As bystanders, unless we have specialist training, car crashes only serve to emphasise the pain of our helplessness at the destructive intervention of larger forces, and there is something especially plangent about these forgotten car crashes of yesteryear. In a single violent event, each one dramatises the sense of loss that time itself engenders, as over the years our tenderest beloved are taken from us. And they charge the photographic space, so that even those images without crashes acquire an additional emotionalism, the poignancy of transience and the imminence of potential disaster. I can think of no more touching image of loneliness that the anonymous figure in Colin O’Brien’s photograph, crossing the Clerkenwell Rd in the snow on New Year’s Eve, 1961.

After he had seen the interior of Herbal Hill Buildings, Colin confided to me he would rather live in Victoria Dwellings that stood there before, and yet, as he returned the keys to Tomasz, the superintendent, he could not resist asking if he might return and take more pictures in different conditions, at a different time of day or when it was raining. And Tomasz graciously assented as long as the apartment remained vacant.

I understood that Colin needed the opportunity to come back again, once that the door to the past had been re-opened, and, I have to confess to you that, in spite of myself, I could not resist thinking, “Maybe there’ll be a car crash next time?” Yet Colin never did go back and now he is gone from this world too.

Accident in the rain.

Accident in the rain, 2.

Accident at night, 1959.

Snow on New Year’s Eve, 1961.

Trolley buses, nineteen fifties.

Clerkenwell Italian parade, nineteen fifties.

Firemen at Victoria Dwellings, nineteen fifties.

Have a Guinness when you’re tired.

Colin’s photograph of the junction of the Clerkenwell Rd and Faringdon Rd, taken from Herbal Hill Buildings on the site of the former Victoria Dwellings.

When Colin O’Brien saw his childhood view for the first time in fifty years.

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Stephen Gill’s Trolley Portraits

When photographer Stephen Gill slipped a disc carrying heavy photographic equipment a few years ago, he had no idea what the outcome would be. The physiotherapist advised him to buy a trolley for all his kit, and the world became different for Stephen – not only was his injured back able to recover but he found himself part of a select group of society, those who wheel trolleys around. And for someone with a creative imagination, like Stephen, this shift in perspective became the inspiration for a whole new vein of work, manifest in the fine East End Trolley Portraits you see here today.

Included now within the camaraderie of those who wheel trolleys – mostly women – Stephen learnt the significance of these humble devices as instruments of mobility, offering dominion of the pavement to their owners and permitting an independence which might otherwise be denied. More than this, Stephen found that the trolley as we know it was invented here in the East End, at Sholley Trolleys – a family business which started in the Roman Rd and is now based outside Clacton, they have been manufacturing trolleys for over thirty years.

In particular, the rich palette of Stephen Gill’s dignified portraits appeals to me, veritable symphonies of deep red and blue. Commonly, people choose their preferred colour of trolley and then co-ordinate or contrast their outfits to striking effect. All these individuals seem especially at home in their environment and, in many cases – such as the trolley lady outside Trinity Green in Whitechapel, pictured above – the colours of their clothing and their trolleys harmonise so beautifully with their surroundings, it is as if they are themselves extensions of the urban landscape.

Observe the hauteur of these noble women, how they grasp the handles of their trolleys with such a firm grip, indicating the strength of their connection to the world. Like eighteenth century aristocrats painted by Gainsborough, these women claim their right to existence and take possession of the place they inhabit with unquestionable authority. Monumental in stature, sentinels wheeling their trolleys through our streets, they are the spiritual guardians of the territory.

Photographs copyright © Stephen Gill

Vanishing London

Four Swans, Bishopsgate, photographed by William Strudwick & demolished 1873

In 1906, F G Hilton Price, Vice President of the London Topographical Society opened his speech to the members at the annual meeting with these words – ‘We are all familiar with the hackneyed expression ‘Vanishing London’ but it is nevertheless an appropriate one for – as a matter of fact – there is very little remaining in the City which might be called old London … During the last sixty years or more there have been enormous changes, the topography has been altered to a considerable extent, and London has been practically rebuilt.’

These photographs are selected from volumes of the Society’s ‘London Topographic Record,’ published between 1900 and 1939, which adopted the melancholy duty of recording notable old buildings as they were demolished in the capital. Yet even this lamentable catalogue of loss exists in blithe innocence of the London Blitz that was to come.

Bell Yard, Fleet St, photographed by William Strudwick

Pope’s House, Plough Court, Lombard St, photographed by William Strudwick

Lambeth High St photographed by William Strudwick

Peter’s Lane, Smithfield, photographed by William Strudwick

Millbank Suspension Bridge & Wharves, August 1906, photographed by Walter L Spiers

54 & 55 Lincoln’s Inn Fields and the archway leading into Sardinia St, demolished 1912, photographed by Walter L Spiers

Sardinian Chapel, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, August 1906, demolished 1908, photographed by Walter L Spiers

Archway leading into Great Scotland Yard and 1 Whitehall, September 1903, photographed by Walter L Spiers

New Inn, Strand, June 1889, photographed by Ernest G Spiers

Nevill’s Court’s, Fetter Lane, March 1910, demolished 1911, photographed by Walter L Spiers

14 & 15 Nevill’s Court, Fetter Lane, demolished 1911

The Old Dick Whittington, Cloth Fair, April 1898, photographed by Walter L Spiers

Bartholomew Close, August 1904, photographed by Walter L Spiers

Williamson’s Hotel, New Court, City of London

Raquet Court, Fleet St

Collingwood St, Blackfriars Rd

Old Houses, North side of the Strand

Courtyard of 32 Botolph Lane, April 1905, demolished 1906, photographed by Walter L Spiers

32 Botolph Lane, April 1905, demolished 1906, photographed by Walter L Spiers

Bird in Hand, Long Acre

Houses in Millbank St, September 1903, photographed by Walter L Spiers

Door to Cardinal Wolsey’s Wine Cellar, Board of Trade Offices, 7 Whitehall Gardens

Old Smithy, Bell St, Edgware Rd, demolished by Baker St & Edgware Railway

Architectural Museum, Cannon Row, Westminster

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Insitute

You may also like to look at

An Alternative Scheme For Liverpool St Station

Henrietta Billings, Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage asks if the demolition and tower scheme is the only way to pay for station improvements at Liverpool St, as Network Rail claim. She introduces John McAslan’s alternative scheme, offering a sympathetic solution that delivers Network Rail’s ambitions without ruining the station or subjecting passengers to years of disruption.

The improved concourse in John McAslan’s scheme (courtesy of JMP)

If you are one of the thousands who pass through Liverpool St Station regularly, you will be familiar with its magnificent features: the light-filled, triple-height concourse, the beautiful Victorian train sheds, and its illustrious adjacent neighbour, the grade II* former Great Eastern Hotel. With 270,000 people using the station every weekday, it is now the busiest terminus in the country. Everyone recognises it needs upgrades, like new escalators, lifts and more accessible toilets. The question is how can they be achieved without ripping out the guts of this well-loved landmark that is – at least theoretically – protected through its grade II listing and Conservation Area status?

Thanks to a number of highly controversial planning applications, Liverpool St Station is at the centre of a raging debate over how we fund essential upgrades to public buildings. Plans by Network Rail to build a nineteen-storey office block through the station are due to be considered by the Corporation of London on 10th February – with a recommendation for approval. Yet the plans have been met with significant opposition from commuters, residents and conservation groups since they were submitted in April last year (2,400 letters of objection, and counting).

The plans would see the beautiful concourse completely demolished. A new tower would loom over the remains of the original station and the historic hotel, and block out light from the rebuilt concourse. 50 Liverpool St, the Gothic revival masterpiece painstakingly built as part of the eighties conservation project, would be demolished, and the works would cause years of significant disruption to passengers. On heritage grounds alone, the City should refuse the plans because they contravene the City’s polices on heritage protection in relation to listed buildings and conservation areas. Additionally, the report we commissioned from sustainability expert Simon Sturgis shows the environmental credentials of the glass and steel tower fall short of the Corporation’s own sustainability ambitions.

Indeed, Network Rail’s £1.2bn proposal is “not technically viable” according to their own advisors and so far they have refused to release the actual costs of the station improvements. Given that the whole project was predicated on the need for the office block to fund the essential upgrades, releasing costs is essential both as a matter of transparency, and to assess the acceptability of what is on the table.

The proposal, designed by Acme Architects, follows an equally controversial application in 2023 by Herzog & de Meuron architects, which was shelved after also receiving thousands of objections including a strong rebuttal from Historic England. They objected “in the strongest terms” to what they argued were “fundamentally misguided” plans and called for a “comprehensive redesign” to avoid the harm caused by the scheme. Confusingly. this previous scheme has not been officially withdrawn, and remains in limbo as a “live” planning submission. In the words of Building Design senior writer Tom Lowe, it has been arguably the most chaotic development process of any major project over the past decade.

Against the backdrop of these competing contentious proposals, a new approach has emerged from a different team of architects and engineers. John McAslan + Partners, the architects behind the celebrated transformation of King’s Cross Station, have unveiled a fresh vision which shows that the station enhancements and accessibility upgrades could be achieved at half the cost, with a sympathetic, lighter-touch design.

When John McAslan + Partners approached SAVE six months ago with their scheme we immediately jumped at the opportunity to show there is an alternative way of providing the much-needed improvements to the station. We believe this proposal is an elegant design solution in the spirit of traditional railway architecture without the passenger disruption, demolition or over-scaled development currently on offer. It is an important contribution to a critical debate about how we develop our public buildings balancing heritage and commercial interests.

Working with architects on alternative schemes is a key campaign tactic that we use at SAVE - from Smithfield Market in Farringdon and the Little Houses on the Strand next to Somerset House, to Battersea Power Station and the mighty Wentworth Woodhouse in Rotherham, South Yorkshire. We know from fifty years of experience how powerful they can be in bringing fresh perspectives and impetus to contested development plans or important threatened landmarks.

John McAslan’s concept has been welcomed by Sir Tim Smit, founder of the pioneering Eden Project, and by heritage and sustainability experts alike as a helpful contribution to a debate that has so far been dominated by one idea: large-scale demolition and a nineteen-storey tower. We regard the McAslan approach as a compelling and viable alternative which is why we are calling on Network Rail and the City of London to pause the current scheme and give full consideration to this approach.

There is still time for Network Rail to get back on the right track. They should pause the Network Rail/Acme scheme for two reasons.

-

Costings of the required station upgrades have not been provided – so it is not possible to assess the full public benefit or justification for such massive and destructive over-station development in relation to the listed building and the conservation area.

-

The Corporation of London and Network Rail need more time to consider fully the heritage, financial and operational opportunities provided by the McAslan approach. The councillors on the planning committee can make this happen by voting to defer the planning application until they have had the chance to review this new information.

The committee date is approaching fast. Please add your voice by submitting your views on the Network Rail/Acme scheme and the alternative vision before 10th February.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN HOW TO OBJECT

Instead of a nineteen-storey tower over the concourse, John McAslan + Partners propose a new steel office building cantilevered over the train sheds. The development could be delivered through access from the west without any interference to trains and is fully reversible. (courtesy of JMP)

The Liverpool St entrance is unaltered in John McAslan’s scheme, with the new cantilevered offices just visible (courtesy of JMP)

Looking from the concourse towards the historic train sheds (courtesy of JMP)

The Herzog & de Meuron scheme (courtesy of Herzog & de Meuron)

The Acme scheme (courtesy of Acme)

You may also like to read about

Towering Folly At Liverpool St Station

Colin O’Brien, Photographer

I am giving an illustrated lecture about Colin O’Brien, the Clerkenwell Photographer, on Tuesday 10th February at 6:30pm at Islington Museum, 245 St John St, EC1V 4NB. Entry is free and no booking is required, just come along.

Observe this tender photograph of Raymond Scallionne and Razi Tuffano in Hatton Garden in 1948, one of the first pictures taken by Colin O’Brien – snapped when he was eight years old, the same age as his subjects. Colin forgot this photograph for over half a century until he discovered the negative recently and made a print, yet when he saw the image again he immediately remembered the boys’ names and recalled arranging them in front of the car to construct the most pleasing composition for the lens of his box brownie.

Colin grew up fifty yards from Hatton Garden in Victoria Dwellings, a tenement at the junction of Faringdon Rd and Clerkenwell Rd – the centre of his childhood universe in Clerkenwell, that Colin portrayed in spellbinding photographs which evoke the poetry and pathos of those forgotten threadbare years in the aftermath of World War II. “We had little money or food, and shoes were a luxury. I remember being given my first banana and being told not to eat it in the street where someone might take it,” he told me, incredulous at the reality of his own past,“Victoria Dwellings were very run down and I remember in later years thinking, ‘How did people live in them?’”

Blessed with a vibrant talent for photography, Colin created images of his world with an assurance and flair that is astounding in one so young. And now these pictures exist as a compassionate testimony to a vanished way of life, created by a photographer with a personal relationship to all his subjects. “I just wanted to record the passage of time,” Colin told me with modest understatement, “There were no photographers in the family, but my Uncle Will interested me in photography. He was the black sheep, with a wife and children in Somerset and girlfriends in London, and he used to come for Sunday lunch in Victoria Dwellings sometimes. One day he brought me a contact printing set and he printed up some of my negatives, and even now I can remember the excitement of seeing my photographs appear on the paper.”

Colin O’Brien’s clear-eyed Clerkenwell pictures illustrate a world that was once familiar and has now receded far away, yet the emotionalism of these photographs speaks across time because the human detail is touching. Here is Colin’s mother spooning tea from the caddy into the teapot in the scullery and his father at breakfast in the living room before walking up the road to the Mount Pleasant Sorting Office, as he did every day of his working life. Here is Mrs Leinweber in the flat below, trying to eke out the Shepherd’s Pie for her large family coming round for dinner. Here is the Rio Cinema where Colin used to go to watch the continuous programme, taking sandwiches and a bottle of Tizer, and forced to consort with one of the dubious men in dirty raincoats in order to acquire the adult escort necessary to get into the cinema. Here is one of the innumerable car crashes at the junction of Clerkwenwell Rd and Faringdon Rd that punctuated life at Victoria Dwellings – caused by lights that were out of sync, instructing traffic to drive in both directions simultaneously – a cue for Colin to reach out the window of their top floor flat to capture the accident with his box brownie and for his mother to scream, “Colin, don’t lean out too far!”

At fifteen years old, Colin’s parents bought him Leica camera. “They couldn’t afford it and maybe it came off the back of a lorry, but it was a brilliant present – they realised this was what I wanted to do,” he admitted to me with an emotional smile. “My first job was at Fox Photo in the Faringdon Rd. I worked in the library, but I spent all my time hanging around in the dark room because that was where all the photographers were and I loved the smell of fixer and developer.” he recalled, “And if I stayed there I would have become a press photographer.” But instead Colin went to work in the office of a company of stockbrokers in Cornhill in the City and then for General Electric in Holborn – “I hated offices but I aways got jobs in them” – before becoming a photographic lab technician at St Martins School of Art and finally working for the Inner London Education authority in Media Resources, a role that enabled him to pursue his photography as he pleased throughout his career.

Over all this time, Colin O’Brien has pursued his talent and created a monumental body of photography that amounts to over half a million negatives, although his work is barely known because he never worked for publication or even for money, devoting himself single-mindedly to taking pictures for their own sake. Yet over the passage of time, as a consequence of the purism of his approach, the authority of Colin O’Brien’s superlative photography – distinguished by its human sympathy and aesthetic flair – stands comparison with any of the masters of twentieth century British photography.

Members of the Leinweber family playing darts at the Metropolitan Tavern, Clerkenwell Rd, 1954.

Girl in a party dress in the Clerkwenwell Rd, nineteen fifties.

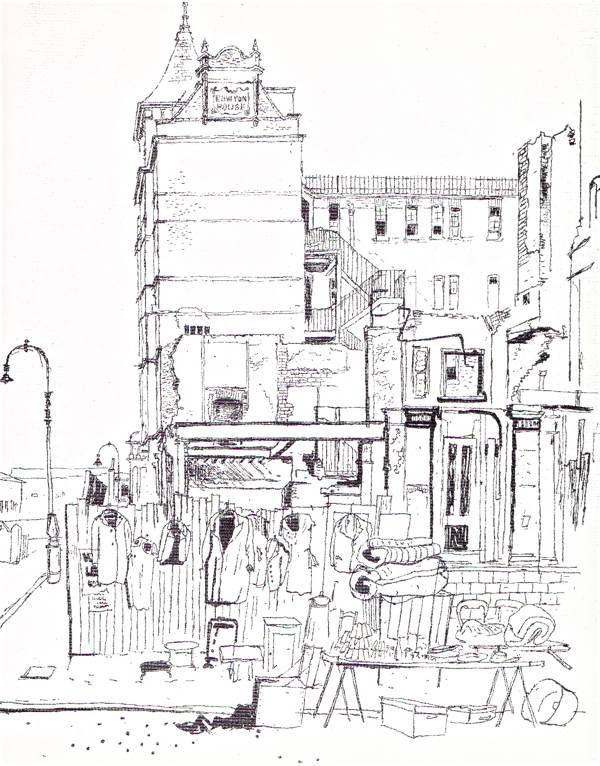

Solmans Secondhand Shop, Skinner St, Clerkwenwell, 1963.

Colin’s mother puts tea in the teapot, in the scullery at Victoria Dwellings, nineteen fifties.

Linda Leinweber takes a nap, 117 Victoria Dwellings, nineteen fifties.

Colin’s father eats breakfast before a day’s work at the Mount Pleasant Sorting Office.

Jimmy Wragg and Bernard Roth jumping on a bomb site in Clerkenwell, late fifties.

Accident at the junction of Clerkwell Rd and Faringdon Rd, 1957.

Mrs Leinweber ekes out the the Shepherd’s Pie among her family, Victoria Dwellings, 1959.

Rio Cinema, Skinner St, Clerkenwell, 1954.

Hazel Leinweber, Victoria Dwellings, nineteen fifties.

Fire at Victoria Dwellings, mid-fifties.

Colin’s mother outside her door, 99 Victoria Dwellings, nineteen fifties.

Boy at Woolworths, Exmouth Market, 1954.

Two women with a baby in Woolworths, Exmouth Market, 1954.

Cleaning the windows in the snow, Clerkenwell Rd, 1957.

Cowboy and girlfriend, 1960.

Nun sweeping in the Clerkenwell Rd, nineteen sixties.

Colin’s window at Victoria Dwellings was on the far right on the top floor.

An old lady listens, awaiting meals on wheels in Northcliffe House, Clerkenwell, late seventies.

The demolition of Victoria Dwellings in the nineteen seventies.

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Barry Rogg Of Rogg’s Delicatessen

Alan Dein remembers Barry Rogg and his celebrated Whitechapel delicatessen

Barry Rogg by Shloimy Alman, 1977

As the years tick by and the places and the people I have loved pass on, I would like to take this opportunity to reflect on a remarkable character whose shop was an East End institution for over fifty years.

Just south of Commercial Rd, Rogg’s delicatessen stood at the junction of Cannon Street Rd and Burslem St with its white-tiled doorway directly on the corner. One step transported you into a world of ‘heimishe’ or homely Jewish food that still had one foot in the past, a land of old-time street market sellers and their Eastern European roots.

Rogg’s was crammed from floor to ceiling with barrels, tins and containers of what Barry Rogg always called “the good stuff”. He was the proud proprietor who held court from behind the counter, surrounded on all sides by his handpicked and homemade wares. The shelves behind him were lined with pickles and a variety of cylindrical chub-packed kosher sausages dangled overhead.

Barry’s appearance was timeless, a chunky build with a round face that sometimes made him look younger or older than he was. He would tell you the story of Rogg’s if you wanted to know, but he was neither sentimental about the heyday of the ‘Jewish East End’ nor did he run a nostalgia-driven emporium. Rogg’s customers were varied and changed with the times. There was always the Jewish trade but, up to their closure, Rogg’s was also a popular a haunt for dockers who would traipse up from the nearby Thames yards. After that his customers were made up from the local Asian community, until there came another wave when he was being discovered by the national press increasingly focusing eastwards.

Barry’s grandfather started in the business at another shop on the same street in 1911. By 1944, when Barry was fourteen and still at school, he had already begun to help the family out at their new corner shop at 137 Cannon Street Rd. In 1946 he moved in for good, though he had only anticipated it would be a two-year stint as the building was earmarked for compulsory purchase for a road widening scheme that fortunately never happened.

I got to know Barry Rogg in 1987 when I joined a team of part-time workers at the Museum of the Jewish East End – now the Jewish Museum – who were collecting reminiscences and artefacts relating to East End social history. Then Rogg’s was one of the very last of its kind in East London. By the nineties it was Barry alone who was flying the flag for the Yiddisher corner deli scene that had proliferated in Whitechapel from the late nineteenth century. Thankfully, due to his popularity and the uniqueness in the last decade of the twentieth century, we have some wonderful photographs and articles to remember Barry by.

There are tantalising images of the food but we no can longer taste it. An array of industrial-sized plastic buckets filled with new green cucumbers, chillies, bay leaves and garlic at various stages of pickling, the spread of homemade schmaltz herrings, fried fish, gefilte fish, salt beef, chopped liver, the cheesecake. I am sure everyone reading this who visited Rogg’s will remember how their senses went into overdrive. The smells of the pickles, the herrings, the fruit and the smoked salmon, the visual bombardment of all the packaging and the handwritten labels. “Keep looking” was a favourite Barry catchphrase and how could you possibly not?

Of course, you could spend all day listening to the banter with his customers. I also fondly recall conversations with his partner Angela, who helped out but generally kept a low profile in the back of the shop. Rogg’s was Barry’s stage. He had a deep love for the theatre and for art, and one wonders what else he might have done if – like so many of his generation – he had not ended up in the family business as a fifteen-year-old out of school.

Barry died in 2006 at the age of seventy-six. Years ago, I co-compiled an album for JWM Recordings, Music is the Most Beautiful Language in the World: Yiddisher Jazz in London’s East End from the twenties to the fifties. As a follow-up, my co-compiler and regular companion on trips to Rogg’s, Howard Williams suggested releasing another disc, this time with a food theme and dedicated to Barry Rogg.

This disc dishes up two sides recorded in New York in the late thirties and forties. Slim Gaillard – whose hip scatological word play would be celebrated in On the Road – performs a paean to the humble yet filling Matzoh Balls, dumplings made of eggs and matzoh meal. Yiddish singer Mildred Rosner serves Gefilte Fish a galloping love affair with this slightly sweet but savoury ancient recipe which consists of patties made of a poached mixture of ground deboned white fish, boiled or fried. These two classic dishes have graced the Jewish luncheon or dinner table for generations and the recipes are included.

On the label is Irv Kline’s portrait of Barry from 1983. Irv was an American who had retired to live in London. Barry’s photograph formed part of Irv’s study of surviving Jewish businesses in the East End, a travelling exhibition which I helped to hang during the eighties. I recall Irv being a real jazz buff so I hope that he too would appreciate the music accompanying his portrait of Barry Rogg.

Click here for information about the ‘Gefilte Fish/Matzoh Balls’ recording

Irv Kline’s portrait of Barry Rogg, 1983

Alan Dein’s photograph of Rogg’s with one of Barry’s regular customers framed in the doorway, 1988

Shloimy Alman’s photograph of Rogg’s interior, 1977

You may also like to take a look at

James Boswell, Artist

A few years ago, I visited a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. She pulled pictures off the wall and books off the shelf to show me his drawings, and then we went round to visit his daughter Sal who lives in the next street and she pulled more works out of her wardrobe for me to see. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

From the vast range of work that James Boswell undertook, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen thirties and the fifties.There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in the human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen-sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards,” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

You might also like to take a look at

In the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher