More From Philip Mernick’s Collection

In this new selection from Philip Mernick‘s fine collection of cartes de visite by nineteenth century East End photographers, gathered over the past twenty years, we publish portraits of women arranged chronologically to show the evolving styles of dress and changing roles of female existence.

1863

1863

1867

1860s

c. 1870

c.1870

c. 1870

1870s

1880

1880s

1880s

1884

1884

1886

1880s

1880s

1880s

1890s

c. 1890

1890s

1890s

c. 1900

c. 1910

c. 1910 Theatrical performer by William Whiffin

c. 1940 Driver

Photographs reproduced courtesy of Philip Mernick

You may also like to take a look at

Last Orders At The Gun

In 1946, a demobbed soldier walked into The Gun in Brushfield St and ordered a pint. Admitting that he had no money, he asked if he could leave his medals as security and come back the next day to pay for his beer. But he never returned and all this time his medals have been kept safely at The Gun, mounted in a frame on the wall, awaiting the day when he might walk through the door again.

Alas, the waiting is over and now it is too late for the soldier to return – because the pub closed forever on Friday and, if he were to come back, he would find The Gun’s doors locked, prior to demolition as part of the impending redevelopment of the handsome London Fruit & Wool Exchange.

The military theme of this anecdote is especially pertinent, since it appears likely that The Gun originated as a tavern serving the soldiers of the Artillery Ground in the sixteenth century, and the story of the pub and the tale of the medals both ended last week.

Contributing Photographer Colin O’Brien & I joined the regulars for a lively yet poignant celebration on Friday night, drinking the bar dry in commemorating the passing of a beloved Spitalfields institution. No-one could deny The Gun went off with a bang.

“We are the last Jewish publicans in the East End,” Karen Pollack, who ran The Gun with her son Marc, informed me proudly, “yet I had never been in a pub until I married David, Marc’s father, in 1978.” Karen explained that David Pollack’s grandparents took over The Bell in 1938, when it was one of eight pubs on Petticoat Lane, and in 1978, David’s father George Pollack also acquired the lease of The Gun, which was run by David & Karen from 1981 onwards.

“David grew up above The Bell and he always wanted to keep his own pub,” Karen recalled fondly, “It was fantastic, everyone knew everyone. We opened at six in the morning and got all the porters from the market in here, and the directors of the Truman Brewery used to dine upstairs in the Bombardier Restaurant – there was no other place to eat in Spitalfields at that time.”

“People still come back and ask me for brandy and milk sometimes,” she confided, “that’s what people from the market drank.”

On Friday night, the beautiful 1928 interior of The Gun with its original glass ceiling, oak panelling, Delft tiles, prints of the Cries of London and views of Spitalfields by Geoffrey Fletcher, was crowded with old friends enjoying the intimate community atmosphere for one last time, many sharing affectionate memories of publican, David Pollack, who died just a few years ago. “We’ve had some good times here,” Karen confessed to me in quiet understatement, casting her eyes around at the happy crowd.

“I was always known as David Pollack’s son, I came into the pub in 2008 and it was second nature to me,” Marc revealed later, which led me me to ask him what this fourth generation East End publican planned to do with the rest of his life. “I’m going to open another pub and call it The Gun,” he assured me without hesitation. And I have no doubt Marc will take the medals with him because – you never know – that errant soldier might still come back for them one day.

Fourth generation East End publican Marc Pollack, pictured here with his staff, stands on the left

David Pollack, publican, Michael Aitken of Truman’s Brewery & George Pollack, publican in 1984

Karen Pollack shows customers the old photographs

Karen Pollack and bar staff

Emma, Marc and Karen Pollack

Medals awaiting the return of their owner

The Gun in 1950

Photographs copyright © Colin O’Brien

You may also like to take a look at

In A Well In Norton Folgate

As part of the SAVE NORTON FOLGATE cultural festival, we are delighted to welcome Jelena Bekvalac Curator of Human Osteology at the Museum of London who will be talking about the excavations of the Priory of St Mary Spital and the human remains that were uncovered there, on Tuesday 3rd March at 6:30pm at The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in Spital Sq. All events in the festival are free – Click here to book your ticket

A little over twenty years ago, eighteen wooden plates and bowls were recovered from a silted-up well in Norton Folgate. One of the largest discoveries of medieval wooden vessels ever made in this country, they are believed to be dishes belonging to the inmates of the long-gone Hospital of St Mary Spital, which gave its name to Spitalfields. After seven hundred years lying in mud at the bottom of the well, the thirteenth century plates were transferred to the Museum of London store in Hoxton where I went to visit them as a guest of Roy Stephenson, Head of Archaeological Collections.

Almost no trace remains above ground of the ancient Hospital of St Mary yet, in Spital Sq, the roads still follow the ground plan laid laid out by Walter Brune in 1197, with the current entrance from Bishopsgate coinciding to the gate of the Priory and Folgate St following the line of the northern perimeter wall. Stand in the middle of Spital Sq today, and you are surrounded by glass and steel corporate architecture, but seven hundred years ago this space was enclosed by the church of St Mary and then you would be standing in the centre of the aisle where the transepts crossed beneath the soaring vault with the lantern of the tower looming overhead. Stand in the middle of Spital Sq today, and the Hospital of St Mary is lost in time.

In his storehouse, Roy Stephenson has eleven miles of rolling shelves that contain all the finds excavated from old London in recent decades. He opened one box containing bricks in a plastic bag that originated from Pudding Lane and were caked with charcoal dust from the Fire of London. I leant in close and a faint cloud of soot rose in the air, with an unmistakable burnt smell persisting after four centuries. “I can open these at random,” said Roy, gesturing towards the infinitely receding shelves lined with boxes in every direction, “and every one will have a story inside.”

Removing the wooden plates and bowls from their boxes, Roy laid them upon the table for me to see. Finely turned and delicate, they still displayed ridges from the lathe, seven centuries after manufacture. Even distorted by water and pressure over time, it was apparent that, even if they were for the lowly inhabitants of the hospital, these were not crudely produced items. At hospitals, new arrivals were commonly issued with a plate or bowl, and drinking cup and a spoon. Ceramics and metalware survive but rarely wood, so Roy is especially proud of these humble platters. “They are a reminder that pottery is a small part of the kitchen assemblage and people ate off wood and also off bread which leaves no trace.” he explained. Turning over a plate, Roy showed me a cross upon the base made of two branded lines burnt into the wood. “Somebody wanted to eat off the same plate each day and made it their own,” he informed me, as each of the bowls and plates were revealed to have different symbols and simple marks upon them to distinguish their owners – crosses, squares and stars.

Contemporary with the plates, there are a number of ceramic jugs and flagons which Roy produced from boxes in another corner of his store. While the utilitarian quality of the dishes did not speak of any precise period, the rich glazes and flamboyant embossed designs, with studs and rosettes applied, possessed a distinctive aesthetic that placed them in another age. Some had protuberances created with the imprints of fingers around the base that permitted the jar to sit upon a hot surface and heat the liquid inside without cracking from direct contact with the source of heat, and these pots were still blackened from the fire.

The intimacy of objects that have seen so much use conjures the presence of the people who ate and drank with them. Many will have ended up in the graveyard attached to the hospital and then were exhumed in the nineties. It was the largest cemetery ever excavated and their remains were stored in the tall brick rotunda where London Wall meets Goswell Rd outside the Museum of London. This curious architectural feature that serves as a roundabout is in fact a mausoleum for long dead Londoners and, of the seventeen thousand souls whose bones are there, twelve thousand came from Spitalfields.

The Priory of St Mary Spital stood for over four hundred years until it was dissolved by Henry VIII who turned its precincts into an artillery ground in 1539. Very little detail is recorded of the history though we do know that many thousands died in the great famine of 1258, which makes the survival of these dishes at the bottom of a well especially plangent.

Returning to Norton Folgate, I walked again through Spital Sq. Yet, in spite of the prevailing synthetic quality of the architecture, the place had changed for me after I had seen and touched the bowls that once belonged to those who called this place home seven centuries ago – and thus the Hospital of St Mary Spital was no longer lost in time.

Drawing of St Mary Spital as Shakespeare knew it, with gabled wooden houses lining Bishopsgate.

“Nere and within the citie of London be iii hospitalls or spytells, commonly called Seynt Maryes Spytell, Seynt Bartholomewes Spytell and Seynt Thomas Spytell, and the new abby of Tower Hyll, founded of good devocion by auncient ffaders, and endowed with great possessions and rents onley for the releffe, comfort, and helyng of the poore and impotent people not beyng able to help themselffes, and not to the mayntennance of chanins, preestes, and monks to lyve in pleasure, nothyng regardyng the miserable people liying in every strete, offendyng every clene person passyng by the way with theyre fylthy and nasty savours.” Sir Richard Gresham in a letter to Thomas Cromwell, August 1538

Finely turned ash bowl.

Fragment of a wooden plate

Turned wooden plate marked with a square on the base to indicate its owner.

Copper glazed white ware jug from St Mary Spital

Redware glazed flagon, used to heat liquid and still blackened from the fire seven hundred years later.

White ware flagon, decorated in the northern French style.

A pair of thirteenth century boots found at the bottom of the cesspit in Spital Sq.

The gatehouse of St Mary Spital coincides with the entrance to Spital Sq today and Folgate St follows the boundary of the northern perimeter .

Bruyne:

- My vowes fly up to heaven, that I would make

- Some pious work in the brass book of Fame

- That might till Doomesday lengthen out my name.

- Near Norton Folgate therefore have I bought

- Ground to erect His house, which I will call

- And dedicate St Marie’s Hospitall,

- And when ’tis finished, o’ r the gates shall stand

- In capitall letters, these words fairly graven

- For I have given the worke and house to heaven,

- And cal’d it, Domus Dei, God’s House,

- For in my zealous faith I now full well,

- Where goode deeds are, there heaven itself doth dwell.

(Walter Brune founding St Mary Spital from ‘A New Wonder, A Woman Never Vexed’ by William Rowley, 1623)

You may also like to read about

In the Rotunda at the Museum of London

The Gentle Author Broke An Arm Yesterday

Dear Readers,

I have to confess that I fell over and broke my right arm which is now in a plaster cast.

For a writer, there can be disastrous consequences to such a mishap but, with the generous assistance of a few kind friends, I shall endeavour to keep publishing a story daily as usual.

Be assured, I will do my utmost not to disappoint you, while taking comfort in the knowledge that you will understand if all is not quite as usual over the next month or so.

I am your loyal servant

The Gentle Author

Mr Pickwick In Brick Lane

It is my delight to present Charles Dickens’ raucous account of a visit by Sam & Tony Weller to the Brick Lane Temperance Association from The Pickwick Papers with drawings by illustrator & printmaker Paul Bommer.

The first ever staging of any of Dickens’ works was a production of The Pickwick Papers at the City of London Theatre, Norton Folgate, in 1837 – even before all the installments were published.

Next week, the esteemed Dickensian Professor Michael Slater will be presenting Dickens’ readings from The Pickwick Papers as part of the SAVE NORTON FOLGATE festival on Thursday 26th February at the Water Poet in Folgate St at 6:30pm. – Click here to book your free ticket.

The monthly meetings of the Brick Lane Branch of the United Grand Junction Ebenezer Temperance Association were held in a large room, pleasantly and airily situated at the top of a safe and commodious ladder. The president was the straight-walking Mr Anthony Humm, a converted fireman, now a schoolmaster and occasionally an itinerant preacher, and the secretary was Mr Jonas Mudge, chandler’s shopkeeper, an enthusiastic and disinterested vessel, who sold tea to the members.

Previous to the commencement of business, the ladies sat upon forms and drank tea, till such time as they considered it expedient to leave off, and a large wooden money box was conspicuously placed upon the green baize cloth of the business-table, behind which the secretary stood and acknowledged, with a gracious smile, every addition to the rich vein of copper which lay concealed within.

On this particular occasion the women drank tea to a most alarming extent, greatly to the horror of Mr Weller, senior, who, utterly regardless of all Sam’s admonitory nudgings, stared about him in every direction with the most undisguised astonishment. “Sammy,” whispered Mr Weller, “if some o’ these here people don’t want tappin’ to-morrow mornin’, I ain’t your father, and that’s wot it is. Why, this here old lady next me is a-drowndin’ herself in tea.” “Be quiet, can’t you?” murmured Sam.

“If this here lasts much longer, Sammy,” said Mr Weller, in the same low voice, “I shall feel it my duty, as a human bein’, to rise and address the cheer. There’s a young ‘ooman on the next form but two, as has drunk nine breakfast cups and a half, and she’s a-swellin’ wisibly before my wery eyes.”

There is little doubt that Mr Weller would have carried his benevolent intention into immediate execution, if a great noise, occasioned by putting up the cups and saucers, had not very fortunately announced that the tea-drinking was over. The crockery having been removed, the table with the green baize cover was carried out into the centre of the room, and the business of the evening was commenced by Mr Tadger, an emphatic little man, with a bald head and drab shorts, who suddenly rushed up the ladder, at the imminent peril of snapping the two little legs incased in the drab shorts, and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I move our excellent brother, Mr Anthony Humm, into the chair.”

Silence was then proclaimed by Mr Tadger, and Mr Humm rose and said – That, with the permission of his Brick Lane Branch brothers and sisters, the secretary would read the report of the Brick Lane Branch committee, a proposition which was received with a demonstration of pocket-handkerchiefs. The secretary having sneezed in a very impressive manner, and the cough which always seizes an assembly, when anything particular is going to be done, having been duly performed, the following document was read:

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF THE BRICK LANE BRANCH OF THE UNITED GRAND JUNCTION EBENEZER TEMPERANCE ASSOCIATION. Your committee have pursued their grateful labours during the past month, and have the unspeakable pleasure of reporting the following additional cases of converts to Temperance.

H. WALKER, tailor, wife, and two children. When in better circumstances, owns to having been in the constant habit of drinking ale and beer, says he is not certain whether he did not twice a week, for twenty years, taste “dog’s nose,” which your committee find upon inquiry, to be compounded of warm porter, moist sugar, gin, and nutmeg (a groan, and “So it is!” from an elderly female). Is now out of work and penniless, thinks it must be the porter (cheers) or the loss of the use of his right hand, is not certain which, but thinks it very likely that, if he had drunk nothing but water all his life, his fellow workman would never have stuck a rusty needle in him, and thereby occasioned his accident (tremendous cheering). Has nothing but cold water to drink, and never feels thirsty (great applause).

BETSY MARTIN, widow, one child, and one eye. Goes out charing and washing, by the day, never had more than one eye, but knows her mother drank bottled stout, and shouldn’t wonder if that caused it (immense cheering). Thinks it not impossible that if she had always abstained from spirits she might have had two eyes by this time (tremendous applause). Used, at every place she went to, to have eighteen-pence a day, a pint of porter, and a glass of spirits, but since she became a member of the Brick Lane Branch, has always demanded three-and-sixpence (the announcement of this most interesting fact was received with deafening enthusiasm).

HENRY BELLER was for many years toast master at various corporation dinners, during which time he drank a great deal of foreign wine, may sometimes have carried a bottle or two home with him, is not quite certain of that, but is sure if he did, that he drank the contents. Feels very low and melancholy, is very feverish, and has a constant thirst upon him, thinks it must be the wine he used to drink (cheers). Is out of employ now and never touches a drop of foreign wine by any chance (tremendous plaudits).

THOMAS BURTON is purveyor of cat’s meat to the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs, and several members of the Common Council (the announcement of this gentleman’s name was received with breathless interest). Has a wooden leg, finds a wooden leg expensive, going over the stones, used to wear second-hand wooden legs, and drink a glass of hot gin-and-water regularly every night – sometimes two (deep sighs). Found the second-hand wooden legs split and rot very quickly, is firmly persuaded that their constitution was undermined by the gin-and-water (prolonged cheering). Buys new wooden legs now, and drinks nothing but water and weak tea. The new legs last twice as long as the others used to do, and he attributes this solely to his temperate habits (triumphant cheers).

Anthony Humm now moved that the assembly regale itself with a song. Brother Mordlin had adapted the beautiful words of “Who hasn’t heard of a Jolly Young Waterman?” to the tune of the Old Hundredth, which he would request them to join him in singing (great applause). It was a temperance song (whirlwinds of cheers).

The neatness of the young man’s attire, the dexterity of his feathering, the enviable state of mind which enabled him in the beautiful words of the poet, to “Row along, thinking of nothing at all,” all combined to prove that he must have been a water-drinker (cheers). And what was the young man’s reward? Let all young men present mark this: “The maidens all flocked to his boat so readily.” (Loud cheers, in which the ladies joined.) What a bright example! “The soft sex to a man,” he begged pardon, “to a female – rallied round the young waterman, and turned with disgust from the drinker of spirits” (cheers). The Brick Lane Branch brothers were watermen (cheers and laughter). That room was their boat, that audience were the maidens, and he (Mr. Anthony Humm), however unworthily, was “first oars” (unbounded applause).

“Wot does he mean by the soft sex, Sammy?” inquired Mr Weller, in a whisper. “The womin,” said Sam, in the same tone. “He ain’t far out there, Sammy,” replied Mr Weller, “they MUST be a soft sex – a wery soft sex, indeed – if they let themselves be gammoned by such fellers as him.” Then, during the song, the little man with the drab shorts disappeared, returning immediately on its conclusion, and whispered to Mr Anthony Humm, with a face of the deepest importance. “My friends,” said Mr Humm, holding up his hand in a deprecatory manner to bespeak silence, “my friends, a delegate from the Dorking Branch of our society, Brother Stiggins, attends below.”

The little door flew open, and Brother Tadger re-appeared, closely followed by the Reverend Mr Stiggins, who no sooner entered, than there was a great clapping of hands, and stamping of feet, and flourishing of handkerchiefs, to all of which manifestations of delight, Brother Stiggins returned no other acknowledgment than staring with a wild eye, and a fixed smile, at the extreme top of the wick of the candle on the table, swaying his body to and fro, meanwhile, in a very unsteady and uncertain manner.

By this time the audience were perfectly silent, and waited with some anxiety for the resumption of business. “Will you address the meeting, brother?” said Mr Humm, with a smile of invitation. “No, sir,” rejoined Mr. Stiggins. The meeting looked at each other with raised eyelids, and a murmur of astonishment ran through the room.

“It’s my opinion, sir,” said Mr Stiggins, unbuttoning his coat, and speaking very loudly – “that this meeting is drunk, sir. Brother Tadger, sir!” said Mr Stiggins, suddenly increasing in ferocity, and turning sharp round on the little man in the drab shorts, “YOU are drunk, sir!” With this, Mr. Stiggins, entertaining a praiseworthy desire to promote the sobriety of the meeting, and to exclude therefrom all improper characters, hit Brother Tadger on the summit of the nose.

Upon this, the women set up a loud and dismal screaming, and rushing in small parties before their favourite brothers, flung their arms around them to preserve them from danger. An instance of affection, which had nearly proved fatal to Humm, who, being extremely popular, was all but suffocated, by the crowd of female devotees that hung about his neck, and heaped caresses upon him. The greater part of the lights were quickly put out, and nothing but noise and confusion resounded on all sides.

“Now, Sammy,” said Mr Weller, taking off his greatcoat with much deliberation, “just you step out, and fetch in a watchman.” “And wot are you a-goin’ to do, the while?” inquired Sam. “Never you mind me, Sammy,” replied the old gentleman, “I shall ockipy myself in havin’ a small settlement with that ‘ere Stiggins.”

Before Sam could interfere to prevent it, his heroic parent had penetrated into a remote corner of the room, and attacked the Reverend Mr. Stiggins with manual dexterity. “Come off!” said Sam. “Come on!” cried Mr Weller, and without further invitation he gave the Reverend Mr Stiggins a preliminary tap on the head, and began dancing round him in a buoyant and cork-like manner, which in a gentleman at his time of life was a perfect marvel to behold.

Finding all remonstrances unavailing, Sam pulled his hat firmly on, threw his father’s coat over his arm, and taking the old man round the waist, forcibly dragged him down the ladder, and into the street, never releasing his hold, or permitting him to stop, until they reached the corner. As they gained it, they could hear the shouts of the populace, who were witnessing the removal of the Reverend Mr Stiggins to strong lodgings for the night, and could hear the noise occasioned by the dispersion in various directions of the members of the Brick Lane Branch of the United Grand Junction Ebenezer Temperance Association.

Illustrations copyright © Paul Bommer

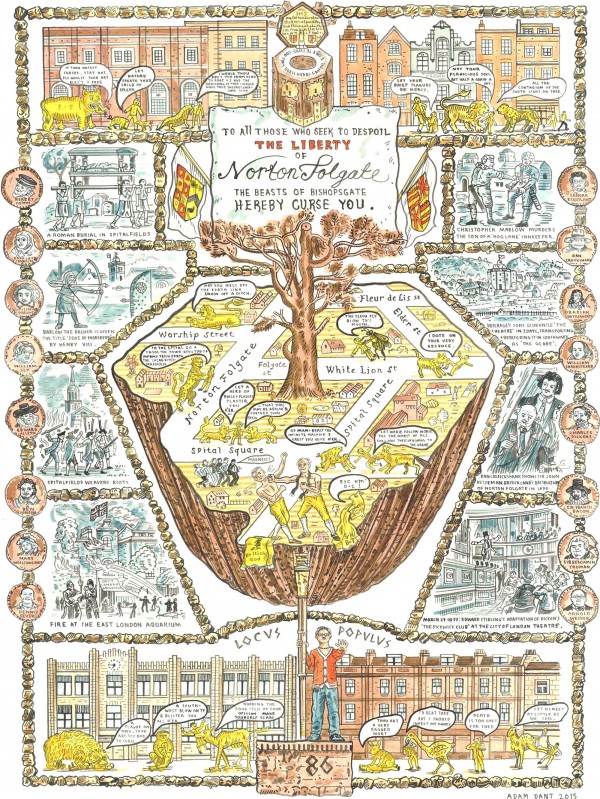

The Ancient Curse Of Norton Folgate

Click on the map to enlarge and study Norton Folgate in detail

Contributing Artist Adam Dant invokes an ancient curse upon despoilers in his new map which forms the centrepiece of the SAVE NORTON FOLGATE exhibition at Dennis Severs House.

“This painstakingly hand-tinted lithograph is produced as a counter to the rapacious practices of the latest shower of uninspired London developers, architects and planners,” he informed me.

“Amongst renderings of the thoroughfares and vignettes of significant moments in the history of the neighbourhood, the beasts who perished in the dreadful fire at the London Aquarium stalk the witless cretins who seek to despoil the unique character of Norton Folgate,” Adam explained with relish, “The animals issue curses in the Jacobean tone of the areas former, colourful, thespian inhabitants.”

Adam Dant is producing a limited edition of thirty copies of his Map of Norton Folgate at £500 each – sized 30” x 22” and all hand-tinted by the artist. Contact AdamDant@gmail.com for purchase enquiries.

A certain Historian socks a certain Architect on the jaw

Click here for a simple guide to HOW TO OBJECT EFFECTIVELY prepared by The Spitalfields Trust

Follow the Campaign at facebook/savenortonfolgate

Follow Spitalfields Trust on twitter @SpitalfieldsT

The Spitalfields Trust’s SAVE NORTON FOLGATE exhibition curated by The Gentle Author is at Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate St, E1

Portraits From Philip Mernick’s Collection

In this selection from Philip Mernick‘s splendid collection of cartes de visite by nineteenth century East End photographers, amassed over the past twenty years, we publish portraits of men in which clothing and uniforms declare the wearer’s identity. All but two are anonymous portraits and we have speculated regarding their occupations, but we welcome further information from any readers who may have specialist knowledge.

Superintendent of a Mission c. 1880

Merchant Navy Officer c. 1880

Policeman c. 1880

Beadle in Ceremonial Dress c. 1900

Private in the Infantry c.1890

Indian Gentleman 1863-5

Naval Recruit c. 1900

Sailor Merchant Navy c.1870

Chorister c. 1890

Merchant Navy Officer c. 1870

East European Gentleman c. 1910

Clergymen c. 1890

Member of a Temperance Fraternity c. 1884

Policeman c.1890

Merchant Navy c. 1870

This sailor’s first medal was given by the Royal Maritime Society for saving a life, his second medal is the Khedive Star Egyptian Medal and the other is the British Egyptian Medal. The ribbon on his cap tells us he served on HMS Champion, the last class of steam-assisted sailing warships. In the early eighteen-eighties, HMS Champion was in the China Sea but it returned to the London Dock for a refit in 1887 when this photograph was taken, before going off to the Pacific.

Photographs reproduced courtesy of Philip Mernick

You may also like to take a look at