At Tim Hunkin’s Workshop

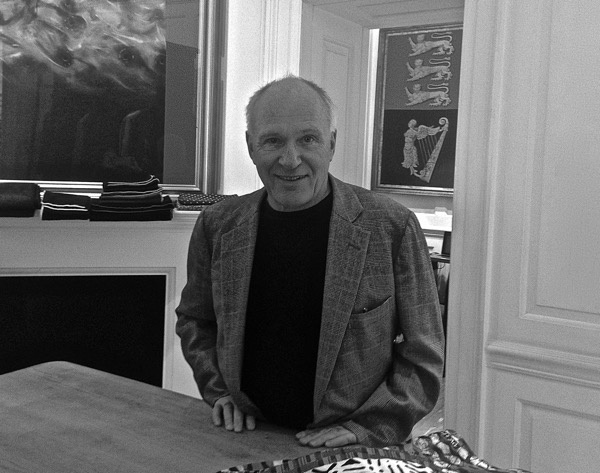

Tim Hunkin at work on his Small Hadron Collider

Apart from the brief trauma of getting locked in the lavatory, it was a relatively uneventful rail journey from Liverpool St up to Suffolk to visit the workshop of Engineer & Cartoonist Tim Hunkin beside the estuary of the river Blythe. A bumpy ride in Tim’s van along the pot-holed track only served to heighten my expectation as we arrived at the water’s edge, where a vast expanse of mud stretched to the horizon reflecting the dramatic East Anglian sky.

A statue of Michael Faraday, parked beside an enormous clock face, a hen coop and a giant pocket calculator, welcomes you the world of Tim Hunkin. Since 1976, Tim has lived here in a cottage at the end of a long brick farmhouse and worked in a series of venerable black weatherboarded sheds. “Back then, The Observer agreed to pay my train fare to London once a fortnight,” he explained, “and that meant I was able to leave London and come to live out here.”

For decades, Tim contributed his Rudiments of Wisdom cartoon strip to the Sunday magazine, but gradually the slot machines took over and now he has two arcades of them – The Under the Pier Show in Southwold and the newly-opened, Novelty Automation in Holborn.

It was a humbling experience to enter the lair of the great inventor and observe him at work. All around were fragments of mechanical devices and intriguing pieces of junk that might one day contribute to one of his creations. Over nearly forty years, Tim has got everything nicely organised, with a wood workshop, a metal workshop, an engineering shop, all kinds of machines, and vast stocks of timber, metal and other stuff.

In spite of the apparent chaos, it is obvious that Tim knows where everything is and can lay his hand upon anything he might require at a moment’s notice. “I’m happiest when I am here in my workshop,” he confided to me and I was startled by the beauty of this unlikely factory, surrounded by trees coming into blossom and all the lush plant growth at the beginning of summer.

The premise of my visit was to view Tim’s latest invention, his Small Hadron Collider which is being unveiled at Novelty Automation in London today and you can go along to try for yourself from tomorrow. Conceived as a satire upon the bizarre world of Particle Physics, it is a based upon a seventies Japanese Patchinko machine that Tim imported from America.

After taking it apart and putting it back together again, Tim created various functions of his own devising and added flip signs with slogans from the world of Quantum Dynamics. Thus Tim’s machine permits even the entirely uneducated individual to have a lot of fun ‘playing’ at Particle Physics and, with only a modicum of application, it is possible to win a Nobel Prize. Who ever dreamed that Scientific Theory could offer such idle amusement?

Whenever Tim finds himself at a loose end or in need of inspiration, he jumps into his old van, negotiates the bumpy track and drives over to enjoy the laughter of visitors at his arcade on the pier at Southwold. I had the privilege of accompanying him that day and, even on a weekday in early summer, we discovered a lively throng. Most remarkable to me was the woman who took a break from walking her dogs to enjoy the dog-walking machine while her patient husband stood holding the leads. Dumbstruck with wonder, I stood contemplating the profound implication of this curious spectacle.

This woman loved walking her dogs so much that she could not resist Tim’s dog-walking machine which offered a virtual experience of equal or superior quality to actual dog-walking. It was the perfect metaphor of our paradoxical relationship with technology and a personal triumph for Tim.

To the Amusements

Tim solves a problem in Quantum Dynamics on his laptop

Tim searches for a screw

Tim demonstrates his metal pressing machine from Clerkenwell

Tim enjoys a thoughtful moment outside his workshop on the estuary of the river Blythe

At Southwold Pier

A woman takes a break from dog walking

Tim’s water clock

Southwold seen from the pier

NOVELTY AUTOMATION at 1a Princeton St, Bloomsbury, WC1. Wednesdays 11am – 6pm, Thursdays 11am – 7pm, Fridays 11am – 6pm & Saturdays 11am – 6pm

You might also like to read about

In Old Finsbury

Does anyone know where Finsbury is anymore? If you ask people, they say “Do you mean Finsbury Park or Finsbury Sq?” It seems that the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury is as lost to us as Atlantis, El Dorado or Shangri La.

Studying Colin O’Brien’s wonderful photographs of Finsbury in the fifties in his forthcoming ‘London Life‘ brought this now-defunct Borough to mind, but it was Arnold Bennett who first led to me to Finsbury to seek the locations of his plangent novel of the booksellers of Clerkenwell, ‘Riceyman Steps.’ Thus it was that I decided to set out with my camera yesterday on a return visit in search of old Finsbury.

Finsbury occupied the site of an ancient fen that lay north of the City of London, but it only formally came into existence as a Parliamentary Borough in 1832 and by 1965 it was absorbed into Islington. Yet Finsbury may be said to be the territory west of Shoreditch, north of the City, east of Holborn and south of Islington – although, in my mind, the heart of Finsbury is around the old Finsbury town hall and it was this area that I chose to explore.

Walking up from Farringdon Station, along Turnmills St and Farringdon Lane, you encounter some of London’s earliest Peabody flats. Finsbury was well served by high quality social housing, from these handsome Victorian brick tenements to the post-war modernist Finsbury Estate on the other side of Clerkenwell – and it is the sympathetic counterpoint between these developments and the old terraces of the bourgeoise that define the personality of the place. A great many of the streets in Finsbury have not changed since Arnold Bennett’s time and the shabby old London that he wrote of may still be glimpsed by the perceptive visitor.

Crossing Rosebery Avenue and walking up Amwell St, you meet fine early-nineteenth century terraces and peaceful squares where a stillness prevails that is exceptional in central London. Major roads hem these streets and render them as backwaters without through traffic.

Willmington Sq is the first you discover, constructed around a small overgrown park and of pleasing domestic scale. Further up the hill, Myddelton Sq is the grandest in Finsbury yet you barely encounter a car there. City University fills up the lost part of Northampton Sq that was demolished, delivering students onto the lawn and encouraging an unexpected atmosphere of youthful fête champêtre.

Lastly, I would never have discovered Granville Sq, if I had not gone in search of ‘Riceyman Steps’ where the protagonist of Arnold Bennett’s novel had his bookshop. Although the bookshops of the steps are long-gone, this modestly-proportioned square paved with old flags and punctuated by manhole covers produced by local foundries is one of my favourites in the capital. Granville Sq may truly said to be part of the London nobody knows.

Looking up Farringdon Lane

Looking along Clerkenwell Rd

Inside Three Kings, Clerkenwell Close

In Pear Tree Court

In Clerkenwell Close

Finsbury Health Centre by Berthold Lubetkin

Joseph Grimaldi lived in Exmouth Market

At the junction of Exmouth Market and Rosebery Avenue

Finsbury Town Hall

Passageway to Lloyd Baker Sq

In Great Percy St

At George Cruikshank’s house in Amwell St

Fig Tree at Clerkenwell Parochial School in Amwell St

Lloyd’s Dairy in Amwell St

In Myddleton Sq

St Mark’s, Myddleton Sq

In Myddleton Sq

In Arlington Way

City University, St John St

In Northampton Sq

In Margery St

In Lloyd Baker St

In Lloyd Baker St

In Granville Sq

Gwynne Place also known as ‘Riceyman Steps’ – leading from Granville Sq to King’s Cross Rd

‘Riceyman Steps’ in 1924

You might also like to read about

How To Write A Blog

One of the delights of teaching courses encouraging others to write blogs is that – without exception – the participants always come up with interesting stories and here are a few recent examples. The next course HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ will be held in Spitalfields on 6th & 7th June. Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book your place.

SOHO TIMES

John Pearse, Soho Tailor

https://sohotimes.wordpress.com

John Pearse’s shop is tucked away in the tiny Georgian Meard Street between Wardour and Dean Streets – and Soho is in his DNA. “I started hanging out in the music bars as a teenager,” he tells me, “Places like the Scene Club in Ham Yard. I was there the day Kennedy was shot, and then there was the Flamingo Club on Wardour Street which was owned by the Gunnell Brothers and offered Mondays, the worst night of the week, to an up and coming group called the Rolling Stones.”

Pearse left school when he was fifteen. “I got a job in a print factory above the Marquee Club on Wardour Street, but it was really noisy and dirty work and I lasted about three weeks,” he says.

So how did he get into tailoring?

“There was this suit I really wanted, so I thought the best way to get it was to learn how to make it myself. I went to Henry Poole on Cork Street, and as I was sitting there David Niven walked in and I thought this is alright, I’ll get to meet lots of famous people. But they didn’t have any work for me and sent me around the corner to Hawes & Curtis on Dover Street and told me to ask for Mr Watson. He was dressed in this amazing double-breasted chalk-striped suit. He sent me to their coat makers’ room up five flights of stairs in this sort of Fagin’s Den where all the apprentice tailors were sitting cross-legged on the floor making coats in a room bathed in sunlight. I’ll never forget that.”

After two years of making coats, Pearse went travelling in Europe, returning to London in 1966 where he helped set up the famous ‘Granny takes a Trip’ boutique in World’s End, on the Kings Road in Chelsea. There it was all velvets and satins and ruffled shirt fronts with lace cuffs worn by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and Brigit Bardot, to name just a few. “But my heart was always in Soho,” says Pearse. “I couldn’t get enough of the music clubs. I remember going to The Bag o’ Nails in Kingley Street when Hendrix debuted, that was the night that Paul McCartney met Linda.”

‘Granny Takes a Trip’ closed in 1969 and Pearse went back to Italy and dabbled in the film industry. “I wound up in Rome and I thought I might get a job as an extra. Fellini was making ‘Satyricon’ at the time, and a very good friend of mine, a model, Donyale Luna, was one of his stars. On Friday nights, there would always be a big dinner party at his house. One night, we went down to the beach and Donyale starts to wade out into the sea, and she thinks she’s Bardot in Joan of Arc, and Fellini is shouting at her to come back, but she keeps going out further and he says to me ‘John can’t you do something?’ And I said, ‘Donyale, if you don’t come back, we’re all going to fuck off and leave you here.’ And Fellini says, ‘John, you’d make a great movie director.'”

Pearse’s one and only feature film was called ‘The Moviemakers’ – a kind of requiem for the Kings Road – and he says he still has nightmares about the sound of heaving cinema seats creaking as people walked out when it was shown at the London Film Festival in 1972. “Critics described it as drug-induced rubbish,” he says, “but it was that film which brought me back to Soho.”

He went back to tailoring and started to get more private clients. He based himself in Royalty Mansions, built in 1908 as flats with workrooms just for tailors, right next door to his current shop which he moved to in 1986. “Soho used to be teeming with tailors working from tiny workshops, first run by Jewish immigrants then the Greeks moved in, and now most of the smaller places have closed down. The craft of tailoring is dying out in Soho. It’s a bit like what’s happened to the film industry,” he says.

“When I was here in the seventies, you could actually hear film being cut as you walked down the street, dodging guys pushing huge reels of film in metal cases. So much of that has disappeared in the last twenty years. Soho has become a sort of gastrodome instead. I miss the delis and the cigar shops in Old Compton Street. I even miss seeing the peep show girls hanging out in doorways. It made for a sort of seedy glamour which has gone now.”

“But I have to be optimistic,” he says. “Soho is much more than just an area of London.”

THE WONDERER

The Fishermen of Burgess Park

Burgess Park rose like a phoenix from the ashes of heavy bomb damage sustained in World War II but, strolling along the park’s tree-lined paths today, you would never know it . A willow gently swept the surface of the lake and beneath it a fisherman was setting his lines. Other fishermen had already set up their rods and were relaxing around the stillness of the water.

Our arrival could not have been better timed. We had just started chatting to a dedicated member of the fifty-strong Burgess Park Angling Club, when one of his three rods started beeping. It was a false alarm – just a pigeon passing under the lines. But then it sounded again – a long, insistent beep. The fisherman leapt for his rod.

“It’s flying! It’s travelling, heading for the ice cream van, see it? Now he’s heading for the fountain.” His rod bowed under the strain. “Got to pump him back. This is why we go for them. Good fighting fish.”

He let the fish run with the line for a while, reeling it in when the line went slack, and then a huge carp with a beautiful golden sheen broke the water.

“My first one of the year!” On land, the fish seemed docile, and its eyes were milky and sunken. “Bit of a manky old thing – battered. I reckon it’s about eighteen pound, just under the twenty mark.”

They gently lowered the old fish back into the water and we watched it slowly slip away into the depths of the lake. Then another fisherman called Bagio came along, a landing net slung over his shoulder, with his young son. “Common?” he asked.

“Yeah, common.”

“I had one yesterday out of here. Twenty-eight pounder,” he said.

From this brief exchange, I gathered that there are more than one type of carp in Burgess Park – Mirror, Liner and Common. I asked how the carp got there in the first place. “Well, the big carp have been here for twenty-five years. Used to be tiddlers – four pounders – but now they’re about two foot long. They brought them from Highgate Ponds. Back then this was a boating lake, the water was crystal clear, but a kid drowned in it so they made it a fishing lake. Then, in 2012, they got millions off the lottery and closed the lake for about six months, so we weren’t feeding the fish and the twenty pounders went down about four pound.” He told me that the Burgess Park Angling Club usually fatten them up with crumbs.

Feeling lucky at having seen the first big catch of the year, I strolled further down the lake and met Robert Neilson, a friendly, laid-back guy, who was fishing with his daughter in the sun. “I’ve had one out today – about twelve pounds. I come down whenever I haven’t got work, almost every week. Doesn’t really matter what the weather is – bit of rain doesn’t stop anyone – not fishermen anyway.”

“This is the place to fish in South London, but Clapham Common’s also good,” he said, “‘There’s tench, bream, pike – a cat fish, sixty pound, meant to be. Lives down the other end.”

Bagio and his son sauntered over. “Catching?” he asked, “That geezer’s just had one. Really manky. But there’s some beautiful carp down there.”

“Pity I didn’t get a fish on the bank for you,” said Robert as we walked away.

I sat on a bench watching the life around the lake surrounded by the cries of moorhens and coots. I watched a pair of Egyptian geese with six goslings paddle across my vision, thinking how incredible it was that all this had been created in just a few decades.

Bagio, and Robert Neilson untangling his line

Robert with his daughter

Burgess Park lake soon after it was built in 1982 (Courtesy of Southwark Local History Library)

CITY SAFARI GIRL

Appledore at Wisteria time

To escape the recent stresses of work I have travelled to the West Country to spend a few days revisiting old haunts from seaside holidays from my childhood. First on the list is Appledore, a quintessential fishing village on the North Devon coast that has somehow avoided mass tourism and retains much of its historical charm.

I remember from my childhood the narrow lanes of pastel-coloured houses, which seem to tumble down to the estuary like blocks of Neopolitan ice cream. At this time of year, the houses are doubly-beautiful as many are clad in drifts of wisteria and the scent from the blooms adds a heady mix when accompanied by a dash of salty air from the sea.

From one of the small shops along the front, I bought a town guide for a pound and followed the trail to discover Appledore’s past. Under a cloud of ivy hedging, I found the plaque to commemorate Appledore’s short-lived railway station. It only ran for ten years as it was not economically viable, going out of business in 1917. Close by is the old Appledore National School which closed in 1969 yet there is rather a poignant faded sign that says the school hall is still available to hire for dances.

Towards one end of Appledore lies a narrow street of brightly-coloured houses, some with cobbled courtyards. This was once a separate district – albeit a small one – called Irsha Street. In the nineteenth century, Irsha folk were said to be at war with their neighbours in Appledore. Such conflict drove the Irsha residents to form a self-contained community, turning their front rooms into to provision stores, where only their Irsha neighbours could shop, and Irsha street had its own pubs – one of which, The Beaver Inn, still survives today.

THE PEREGRINATING PENGUIN

Architecture and urbanism, sailing ships and boat geekery, etc

http://leepenghui.blogspot.co.uk

On Monday, I attended a course at the Royal College of Physicians which gave me the opportunity to have a look around one of the most significant modern buildings in Britain. It is in Regent’s Park next to John Nash’s famous terraces, to which it provides a counterpoint – harmonising beautifully with the older buildings while being uncompromisingly modern.

The College was completed in 1965, the work of modernist architect Denys Lasdun, who later designed the National Theatre, and is regarded as one of his masterpieces. From the outside, the dominant impression is of an imposing horizontal cantilevered white slab resting on a dark base.

The main interior space is dominated by a staircase rising up the middle. A generous budget allowed Lasdun to use luxurious materials and to work with highly-skilled engineers, as seen in the Sicilian marble used in the staircase, the specially commissioned porcelain wall tiles from Candiolo in Italy, the double-storey panes of glass that were the largest that could be manufactured at the time, and the hydraulic wall between two rooms which can be raised to form a single large hall.

It is a pleasure to walk through and explore, with unexpected viewpoints and beautiful details, such as this stairwell, illuminated by a hidden skylight that produces marvellous effects of light and shade

Large windows frame views of the College gardens, and Regent’s Park with its Nash Terraces, which become part of the whole composition

Medicinal Garden containing herbs for remedies and healing

The Royal College of Physicians by Denys Lasdun, Regent’s Park

INSPIRATION

Workroom Profile of David Mitchell, Printmaker

http://www.pentreath-hall.com/inspiration/

For as long as I have known him, David Mitchell has always struck me as a dynamic and progressive individual, open to all the world and its quirkiness – unstoppable in his inquisitiveness and energy to learn and see and do new things. How many eighty-four year olds have you heard of having their first solo exhibition in London?

Born in Hampstead to a Russian-Jewish antique dealer father and Cornish mother, David considered himself an only child from a huge family. He had three, much older, sisters so that by the time David came along they spoiled their little brother rotten. His parents did considerably well for themselves and the family flourished in London before and during the war. David had a brief spell out in South Africa but, back in London, he was sent to a progressive school called King Alfred’s at the heyday of child-centred, democratic, autonomous education. “We made all the rules, the first thing we did was get rid of all the rules. It gave me a lifelong taste of independence and rule breaking which has served me well.”

It was an exciting time when the war ended. After a year studying Music at Cambridge, David left. Having been called up to do his National Service, as a conscientious objector he spent his time as a orderly at the Trade Union Hospital in Hampstead. It proved to be an eye-opening education for him – a young man from a ‘nice’ family in Hampstead – meeting working men from all over the country with their industrial injuries. Yet his creative drive was music – writing, playing and singing.

A second attempt at university saw David dabble in Anthropology – still not quite right. It was a time of being able to get by on very little money, when living was cheap and jobs were easy to come by, so David worked in bookshops and galleries for a decade, until the call to study music at the London University could no longer be ignored. Completing his degree, he began teaching at the Inner London Education Authority Schools – “The great independent education system, before Thatcher came and tore it to shreds.”

By this time, David was living with his partner whom he’d met at the Cuba Missile Demonstration in 1962. Eventually, David became Head of Music at a school in Belsize Park and stayed there for twenty-two years. “By my fifties, I’d stopped writing so much music and started working in visual art. Throughout my fifties and sixties, I would draw at our little cottage in Norfolk and that went on until I retired twelve years ago. I knew I would not be good at having no structure in my life so I thought I’d do a foundation year at the City Lit, but I had no idea how demanding it was going to be! So many expectations took me by surprise but it was thrilling, and printmaking grabbed me.”

Most of David’s prints are photo-etchings, but some come from observational drawings and all are landscapes. “I’m a very bad photographer, so I like to take pictures and turn them into photo-etchings. I’m not a great user of colour, I prefer monochrome – I feel comfortable with it. During the process of making a photo-etching, you can play with altering the image. I like to dry point and aquatint.” From these landscapes, come David’s rather playful abstractions which are concerned with mark-making and the techniques of printmaking as they are about their original source material.

Moonlight No 1

Moonlight No 2

Moonlight No 3

John Mitchell, Printmaker

HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ, 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields, 6th & 7th June

Spend a weekend in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Spitalfields and learn how to write a blog with The Gentle Author.

This course will examine the essential questions which need to be addressed if you wish to write a blog that people will want to read.

“Like those writers in fourteenth century Florence who discovered the sonnet but did not quite know what to do with it, we are presented with the new literary medium of the blog – which has quickly become omnipresent, with many millions writing online. For my own part, I respect this nascent literary form by seeking to explore its own unique qualities and potential.” – The Gentle Author

COURSE STRUCTURE

1. How to find a voice – When you write, who are you writing to and what is your relationship with the reader?

2. How to find a subject – Why is it necessary to write and what do you have to tell?

3. How to find the form – What is the ideal manifestation of your material and how can a good structure give you momentum?

4. The relationship of pictures and words – Which comes first, the pictures or the words? Creating a dynamic relationship between your text and images.

5. How to write a pen portrait – Drawing on The Gentle Author’s experience, different strategies in transforming a conversation into an effective written evocation of a personality.

6. What a blog can do – A consideration of how telling stories on the internet can affect the temporal world.

SALIENT DETAILS

The course will be held at 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields on 6th & 7th June from 10am -5pm on Saturday and 11am-5pm on Sunday. Lunch catered by Leila’s Cafe and tea, coffee and cakes by the Townhouse.

Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book a place on the course.

The Stoke Newington Mulberry

The Stoke Newington Mulberry and George Gilbert Scott’s spire of 1858

Behold the mighty Stoke Newington Mulberry! Over recent weeks, I have introduced you to the Bethnal Green Mulberry, the Haggerston Mulberry, the Dalston Mulberry, the Whitechapel Mulberry and the Oldest Mulberry in Britain. You may be assured that this latest addition to my growing list of magnificent London Mulberries is more than worthy to join its peers.

The Stoke Newington Mulberry is especially favoured by its secluded location, at the centre of the lawn in the vicarage garden with George Gilbert Scott’s monumental spire of St Mary’s New Church towering high overhead. Such a placement proposes an unlikely conversation between Gilbert Scott’s austere Anglican gothic soaring above and the lyrical romance of the Mulberry flourishing beneath in its shade.

Rector Dilly Baker is the custodian of the venerable Mulberry, which she is informed by an authoritative member of her congregation is approximately four hundred and fifty years old – which means it predates almost everything around, except St Mary’s Old Church across the road which was recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086. The Mulberry is certainly old enough for Daniel Defoe to have sat under it when he lived nearby in Stoke Newington Church St at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

The trunk of the Stoke Newington Mulberry collapsed long ago and – like its Syon Park counterpart – it has spread its limbs, taking up the greater part of the lawn and delivering the ideal habitat for a drift of bluebells which are in bloom now to splendid effect. Recently renewed supports for its ancient branches bear testimony to the affection that the Stoke Newington Mulberry draws from its many fond admirers.

This breathtaking horticultural feature at the centre of of the lawn is the ideal conversation piece at the vicarage and one can only wonder how many parishioners have stood around the Mulberry with teacups at fetes and other ecclesiastical gatherings, speculating about its great age and what tales of old Stokey it might tell if only it could talk.

The Stoke Newington Mulberry has recently had its supports renewed

The gnarly trunk of the Stoke Newington Mulberry

Recently planted Mulberry in nearby Clissold Park, Stoke Newington – popular with dogs

You might like to read more about

John James Baddeley, Die Sinker

“I haven’t time in my life for much else than work”

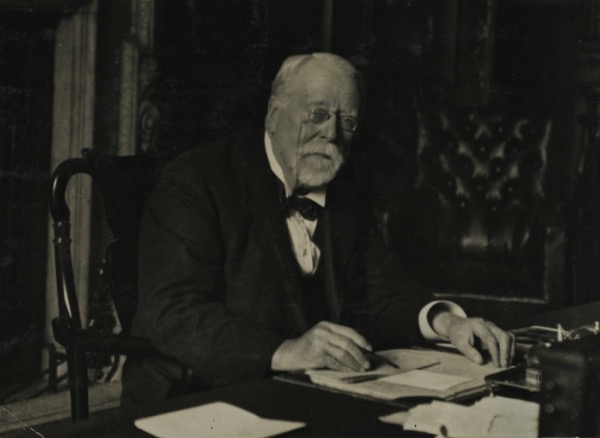

These photographs show Sir John James Baddeley, Baronet – known colloquially as ‘JJ’ – taking a Sunday morning walk with his wife through the empty City of London in 1922, when he was Lord Mayor and residing at the Mansion House.

With his top hat, cane and Edwardian beard, the eighty-year-old gentleman looks the epitome of self-confident respectability and worldly success, yet there is a poignancy in his excursion through the deserted streets, when the hubbub of the week was stilled, pausing to gaze into the windows of the shabby little printshops that competed to supply letterheads and engraved stationery to the banks, stock-brokers and insurance companies of the City.

In those days, all transactions and share issues required elaborately-engraved forms and there was a legal obligation to list all the directors on business notepaper which needed constant reprinting and adjustment of the dies whenever there were staff changes. Consequently, the City of London teemed with small highly-specialised companies eager to fulfil the constant demand for all this printed paper.

At the time of these photographs, nearly sixty years had passed since, at the age of twenty-three in October 1865, JJ had set up independently as a die sinker in a shared workshop in Little Bell Alley at the back of the Bank of England under entirely inauspicious circumstances. The eldest of thirteen children, JJ had already acquired plenty of experience of the long hours of labour required to scrape a modest living in the trade of die-sinking and engraving when he was apprenticed to his father at fourteen years old in Hackney.

Even by the standards of nineteenth century fiction, it was an extraordinary story of personal advancement. JJ oversaw the transformation of his business from an artisan trade to an industrialised process employing hundreds in a single factory. Born into an ever-increasing family that struggled to keep themselves, he inherited a powerful work ethos and a burning desire to overcome the injustice his father had suffered. JJ can only have been a driven man, the eldest brother who set his own modest industry in motion and then drew in his younger siblings to assist with spectacular results.

“In January 1857, I started my business life with my father in his workshop in Hackney at the back of the house at the Triangle in Mare St where I first donned a white apron, turned up my shirt sleeves and did all sorts of jobs,” he wrote of his apprenticeship in the trade of die sinking, “sweeping up and lighting the forge fire, warming the dies and later forging them on the anvil, then annealing them and afterwards filing them to shape and, when engraved, hardening them and tempering them.”

“During the whole time there, I was the errand boy, taking the dies and stamps to the few customers that my father had, Jarrett at No 3 Poulty being the chief one,” he recalled at the end of his life, “Many a time have I trudged – in winter with my feet crippled with chilblains – to the Poultry and at night to his other shop in Regent St. During the time I was at work with my father I had very good health, but we were all poorly-clad and none of the children had overcoats.”

In 1851, Griffith Jarrett exhibited his popular embossing press at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, ordering the dies from JJ’s father who took on a larger house for his growing family and more apprentices on the basis of this seemingly-endless new source of income. Yet Griffith Jarrett exploited the situation mercilessly, inducing JJ’s father to make dies for him alone, then driving the prices down and eventually turning JJ’s father into a mere journeyman who worked like a slave and found he had little left after he had paid his production costs, impoverishing the family.

When, as a boy, JJ walked through the snow at night to deliver the dies for his father to Griffith Jarrett’s Regent St shop at 8pm or 10pm, Jarrett sometimes gave JJ tuppence to ride part of the way home. It was an offence of meagre omission that JJ never forgot. “These two pennies were the beginnings of my savings which enabled me to set up in business for myself and to defy the man who for more than twenty years had my father in his clutches,” admitted JJ in later years.

“I began work by doing simple dies for my father at journeyman prices and began making traces, stops, commas, letter punches and other small tools. By the end of the year, I managed to get a few orders for dies from Messrs John Simmons & Sons who had a warehouse in Norton Folgate,” he recorded, looking back on his small beginnings in the light of his big success, “I turned out my work quicker than my competitors and gave better personal attention to my customers, trusting to this rather than obtaining orders by quoting lower prices.”

“These were very strenuous and hard working times, I commenced work at nine and seldom leaving before ten o’clock at night,” he confessed – but twenty years later, in 1885, the company occupied a six storey factory at the corner of Moor Lane and employed more than three hundred people. It was an astonishing outcome.

Yet, while embracing the potential of technological progress so effectively, JJ possessed an equal passion for craft and tradition – especially the history of Cripplegate where he became a Warden. “In 1889, an attempt to take down the St Giles Church Tower, after a good fight I saved it,” he wrote with succint satisfaction. Later, devoting a year of his life to writing an authoritative history of Cripplegate, he prefaced it with the words – “Let us never live where there is nothing ancient, nothing to connect us with our forefathers.”

No wonder then that, as an old man, John James Baddeley chose to stroll through the empty streets of London on Sunday mornings, pausing to look into old print shop windows, and consider his own place in the long history of printing and the City.

John James Baddeley’s business card

Over 300 hands were employed at Baddeley Brothers in Moor Lane, 1888

Engineering & Press Making Dept in the basement

Paper & Envelope Department on the first floor where over fifty hands are employed in envelope making, gumming, black and silver bordering, scoring etc

Die Sinking & Engraving Dept – The largest in the trade, twenty-one die sinkers are employed alongside twenty-one copperplate engravers and eight wood engravers.

Litho Dept on the second floor with fourteen copperplate presses, three litho machines, nine litho presses and three Waddie lithos

The view from the Mansion House in 1922

JJ in the Venetian Parlour at the Mansion House

You may also like to read about

More Of Janet Brooke’s City Churches

Since I published Janet Brooke‘s linocuts of City Churches last year, she has expanded her portfolio with eight more prints and it is my great pleasure to publish the complete set, as a preview of her new exhibition which runs from 18th May until 19th June at Salvation Army Headquarters, 101 Queen Victoria St, EC4. Janet wants you to know that these were all printed on her Imperial Press, dating from 1832 and manufactured by J. Cope & Sherwin, 5 Cumberland Place, Curtain Rd, Shoreditch.

St Mary-At-Hill

Christ Church Greyfriars

St Clement Eastcheap

St Mary Aldermary

St Olave Jewry

St Peter Cornhill

St Dunstan-In-The-East

Christ Church Spitalfields

St Mary Abchurch

St Mary Somerset

St Edmund King & Martyr

St Stephen Walbrook

St Augustine Watling St

St Nicholas Cole Abbey

St Michael Paternoster Royal

St Benet Paul’s Wharf

St Lawrence Jewry

St Vedast alias Foster

St Alban Wood St

St Magnus the Martyr

St Margaret Lothbury

St Andrew by the Wardrobe

St James Garlickhythe

St Michael Cornhill

St Brides

St Margaret Pattens

St Clement Danes

Images copyright © Janet Brooke

You may also like to take a look at

The City Churches of Old London

Happy Birthday, Colin O’Brien!

Colin with his mother Edith and father Edward in Clerkenwell in the forties

Contributing Photographer Colin O’Brien is seventy-five years old today and we are happy to report that we have sent his book LONDON LIFE to the printers this week. In two hundred and eighty-eight pages, this magnificent monograph collects the cream of Colin’s photographs of London from 1948 until the present day into a large-format hardback.

On publication day Thursday 18th June from 6pm, you are all invited to join us in raising a glass to celebrate the launch of LONDON LIFE and view the accompanying photography exhibition at The Society Club, 12 Ingestre Place, Soho, W1. We shall be giving away free prints of one of Colin O’Brien’s famous Clerkenwell car crash pictures and Colin will be signing copies of LONDON LIFE.

Click here to pre-order your copy of LONDON LIFE direct from Spitalfields Life

Colin O’Brien introduces his LONDON LIFE to be published on 18th June

My mother and father both came from large families of some six or seven children, as was usual in those days. Many did not live beyond infancy, dying from diseases they would survive today, and my mother often talked about her beautiful sister Eileen, who died from pneumonia when she was nine years old. Families were poor and people often went hungry. Children walked long distances to school and shoes were a luxury.

My parents grew up in Clerkenwell, which was called‘Little Italy’ because of the Italian immigrants living there. St Peter’s Roman Catholic Church was the focus of their early lives, along with a building called ‘The Red House’ – with a distinctive red brick exterior still visible in Clerkenwell Road today. This was where they went when they needed a handout of food or clothing.

I was born on May 8th 1940 in Northampton Buildings in Northampton Street in the now-defunct London Borough of Finsbury. Soon after my birth, we moved from there to Victoria Dwellings, a sprawling series of tall Victorian buildings which ran along the junction of Clerkenwell Road and Farringdon Road. Then Edward, my father, left to serve in the Second World War, travelling to Germany, France and Italy before returning when I was five years old. I cried when I saw him again because I wondered who this strange man was.

My mother, Edith, never had a career. She looked after me and her mother, Ada Kelly, who was crippled with arthritis and sat in a chair beside the radio, chuckling at Wilfred Pickles or listening to ‘Mrs Dale’s Diary’. My mother and her sister, Winnie, occasionally went ‘up west’ to look in the stores and try things on, even though they could not afford to buy them. I took some photographs of my mother trying on hats in British Home Stores in Oxford Street and laughing her head off when she saw herself in the mirror.

‘The Dwellings’ – as we called them – had survived the bombing, but were surrounded by derelict buildings and dangerous structures. For us children, these sites became our playgrounds with many exciting adventures to be had. It was part of life that we were allowed to go and play on our own in dangerous places. Our parents were too busy earning a living to worry about us overly. We learned to look after ourselves, but local people also looked out for us and, occasionally, a policeman would clip us round the ear if we were doing something wrong. We stayed out all day and played until we were exhausted, then came home to our tea before we went to bed and sank into a dream world of fantasy and romance.

Our flat was number 118, at the top of the building, and the view from the living room became my first window on the world. It was from here I looked down onto the junction of Clerkenwell Road and Farringdon Road – where I took images of violent car crashes and fatal accidents, and of a window cleaner perched precariously on a high ledge opposite in a snow storm. It was from my window that I saw the annual Italian procession in which I walked as a train bearer when I was six years old. From this aerial perspective, I photographed ‘The Steps’ across Clerkenwell Road in Onslow Street, our usual meeting place as children before setting off for a day’s play on the bomb sites. From the living room, I watched trolley buses, delivery vans and women chatting. One of my photographs captures an almost- deserted crossing on New Year’s Eve with snow falling, taken while we sat during a power cut to see in the New Year by the light of a candle in 1962.

My granny, Ada, lived at number 99 where all the neighbours would gather during the war whenever there was an air raid. They gave up going to the designated shelters, preferring to take their chances at home instead, and number 99 was thought to be safe because it nestled in the centre of the block. People assembled there, drank lots of tea, told stories and cracked jokes to take their minds off the fact that, if a bomb hit, they might all be killed in an instant.

The Leinwebers lived in the flat beneath us at number 117, until their family of seven or eight children grew so large they took over number 116 as well. My mother’s sister, Winnie, married Frank Leinweber, one of the Leinweber boys. I remember, in the late fifties, Mrs Leinweber was still cooking for her children who would pop in for lunch and I photographed her dishing it up in the room that served as her kitchen, living and dining room all in one.

Early pictures show me carrying a box camera around and my first real photograph was of two boys leaning against a car in Hatton Garden. This is where my interest started – there in Clerkenwell in Little Italy in the London Borough of Finsbury, where I grew up with my mum and dad, and my aunts and uncles, and all my friends and acquaintances.

My uncle, William Kelly, was a taxi driver and a bit of an outsider. He rarely turned up for family gatherings but, at Christmas when I was six years old, he arrived with a parcel containing some bottles of chemicals, a printing frame and a couple of dishes. We mixed up the chemicals, took a box camera negative and put it in contact with light sensitive paper held in a small wooden frame. After we exposed it to daylight, we dipped the paper into the developer and I can remember that moment when I first saw an image appear as if from nowhere – it still fascinates and excites me today.

My first photographic impulse was to capture the childhood world that surrounded me in Clerkenwell but, as my universe expanded and I travelled further afield, I continued to take pictures without ceasing. Shaping my perceptions and approach to existence, the life I recorded with my camera made me the man I am today.

My mother, Edith, in the scullery at 118 Victoria Dwellings

This tiny room was where my mother cooked and where we also washed, occasionally putting a tin bath on the floor, filling it with hot water from the geyser, and sitting there as we scrubbed ourselves clean. I remember the noise of the whistling kettle, and I can still smell the eggs and bacon and fried bread that my mother was cooking, accompanied by a steaming hot cup of tea with three sugars to warm me up after playing outside all day.

The oven had seen better days, the enamel was chipped yet it still functioned well enough and, although there was no room for a fridge in the scullery, nobody had one in those days. It was a long time before I realised that well-off people had a room called a ‘kitchen’ where they did their cooking.

I remember my mother and Auntie Winnie going to the Ideal Home Exhibition at Olympia and coming back with exciting ideas about how we could improve our ‘impoverished’ existence. My mother loved bright colours and flowery patterns and modern swivel chairs. She made the effort to brighten up the drab surroundings in Victoria Dwellings, but it all felt so cosy that, as I grew up, I never questioned how we lived. To me it was our home, it was where I felt safe.

My father, Edward, in the living room at 118 Victoria Dwellings

Our front door led straight into the living room where my father sat to eat his breakfast of toast and tea before setting off for work at Mount Pleasant Sorting Office. I could never understand why my mother covered up the gas meter with a piece of curtaining but not the electric meter in this room.

When my father came back from the war with no prospects, little money, and a son and a wife to support, he may well have wished he was back in the army, but eventually he found a job sorting letters. I remember finding a diary of his after he died. One entry read, “Five shillings short on the rent this week, I don’t know what I shall do,” but he must have found the money from somewhere.

I recall him coming to one of my early exhibitions at the Morley Gallery and he wrote in the comments book, “I am very proud of my son and I enjoyed the exhibition very much.”

HERBAL HILL, EARLY FIFTIES Seen from the rooftop of Victoria Dwellings, the Italian Procession in Honour of Our Lady of Mount Carmel snakes its way into Clerkenwell Road in the rain. Huge crowds gathered to view this annual event which still takes place today.

You may also like to read about