Hackney Mosaic Project’s Magnum Opus

We have now raised over £11,000 donated by 142 readers to publish a book of Tessa Hunkin’s Hackney Mosaic but we still have quite a way to go, and only a week left. Click here to learn more and support publication of Tessa Hunkin’s Hackney Mosaic Project

Tessa Hunkin

On Hackney Downs, you can view Hackney Mosaic Project‘s magnum opus, an entire open air theatre covered with a vast lyrical tableau of wild creatures which won Mosaic of the Year 2014 from the British Association for Modern Mosaic.

I visited Tessa Hunkin, the inspirational designer and leader of the project, while she applied the finishing touches of grouting in advance of the unveiling. “It suits us to have our workshop here in the Pavilion on Hackney Downs,” Tessa confided to me, “because the park attracts people from the local community who feel excluded through illness, loneliness or other problems – they see a friendly place and they come and join us making mosaics.”

“We like to do big mosaics, it inspires us to work on an epic scale,” Tessa admitted to me recklessly.

The first visitors arrive to admire the completed mosaics

The model for the design

You may also like to read about

Sophie Charalambous, Artist

Trinity Green Almshouses, Mile End

You only have until this Saturday 3rd May to catch Sophie Charalambous’ new exhibition at Rebecca Hossack Gallery, Conway St, Fitzroy Sq, W1T 6BA. I was captivated by the soulful melancholy beauty of Sophie’s paintings from the moment I saw them, so Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went over to visit her at her studio in London Fields where she has been working in an old garment factory for the past fifteen years. While her faithful hound who sneaks his way into many of the paintings dozed on the sofa, Sophie showed us her sketchbooks and I recognised a kindred spirit in Sophie’s love of the Thames – a romance nurtured by regular visits to the foreshore at Wapping and finding expression in magnificent moody paintings.

House by the Thames at Bankside

Drovers in London Fields

Sophie Charalambous

Life, Still, Winter

Pageant

Wapping Pierhead

On the Beach at Wapping Pierhead

Sketch for Wapping Pierhead, with raindrops

Warehouses in Wapping

Sketch for Trinity Green Almshouses, Whitechapel

Sophie Charalambous in her studio in London Fields

Paintings copyright © Sophie Charalambous

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

In Petticoat Lane

Click here to book for my tour of Petticoat Lane this Saturday

Experience the drama of the celebrated market and meet some those who made it including, Geoffrey Chaucer, Betty Levi, Tubby Isaacs, Franceskka Abimbola, Jeremy Bentham, Fred the Chestnut Seller and the Pet Shop Boys.

Hosted by The Gentle Author, this is a walking tour of storytelling and sightseeing, complemented with archive photography, paintings and music.

Click here to contribute to our crowdfund for TESSA HUNKIN’S HACKNEY MOSAIC PROJECT book.

Mosaic makers, Elspeth, Ken, David, Sheri, Alice, Beryl, Dani and in the front row, Lee, Tessa, Janice

Petticoat Lane Market has a special place in my affections because it was where my parents went on their honeymoon in 1958. Today it commands my respect as the most authentic local market, because Petticoat Lane is not a recreational market as the others are but the place where you go if you need to buy things cheap.

So it was an especial delight to go over there and congratulate Tessa Hunkin and her colleagues from Hackney Mosaic Project, the makers of the new Petticoat Lane mosaic which celebrates the history of the market.

For many months, they have been working to complete the mosaic in the pavilion on Hackney Downs which serves as their workshop and yesterday came to admire their latest creation now installed on the wall of the Petticoat Tower Estate on the west side on Middlesex St.

Even as we stood there, passersby stopped to take photos of themselves in front of the mosaic which gave the proud makers a visible and gratifying confirmation that they have created a popular success.

At the centre of the mosaic is a view down Middlesex St, flanked by roundels of textile designs and the market personalities of yesteryear (including Prince Monolulu and Sid Strong), embellished with images of petticoats. If you look closely, there are even some actual pearl buttons set into the mosaic in honour of the pearly kings and queens.

Afterwards, the mosaic makers took the opportunity for a stroll around the market followed by a hearty lunch at Nora’s Cafe on Wentworth St to celebrate the completion of yet another successful project to add to the dozens of mosaics they have installed over the past ten years which elevate our East End streets with their wit and beauty.

A Spitalfields silk design and Sid Strong, the crockery juggler

A Bengali textile design and an Organ Grinder

A Pearly Queen and a Wax Batik textile design

In Search Of Shakespeare’s London

Sir William Pickering, St Helen’s, Bishopsgate, 1574.

Ever since the discovery of the site of William Shakespeare’s first theatre in Shoreditch, I have found myself thinking about where else in London I could locate Shakespeare. The city has changed so much that very little remains from his time and even though I might discover his whereabouts – such as his lodging in Silver St in 1612 – usually the terrain is unrecognisable. Silver St is lost beneath the Barbican now.

Yet, in spite of everything, there are buildings in London that Shakespeare would have known, and, in each case, there are greater or lesser reasons to believe he was there. As the mental list of places where I could enter the same air space as Shakespeare grew, so did my desire to visit them all and discover what remains to meet my eyes that he would also have seen.

Thus it was that I set out under a moody sky in search of Shakespeare’s London – walking first over to St Helen’s Bishopsgate where Shakespeare was a parishioner, according to the parish tax inspector who recorded his failure to pay tax on 15th November 1597. This ancient church is a miraculous survivor of the Fire of London, the Blitz and the terrorist bombings of the nineteen nineties, and contains spectacular monuments that Shakespeare could have seen if he came here, including the eerie somnolent figure of Sir William Pickering of 1574 illustrated above. There is great charm in the diverse collection of melancholic Elizabethan statuary residing here in this quaint medieval church with two naves, now surrounded by modernist towers upon all sides, and there is a colourful Shakespeare window of 1884, the first of several images of him that I encountered upon my walk.

From here, I followed the route that Shakespeare would have known, walking directly South over London Bridge to Southwark Cathedral, where he buried his younger brother Edmund, an actor aged just twenty-seven in 1607, at the cost of twenty shillings “with a forenoone knell of the great bell.” Again there is a Shakespeare window, with scenes from the plays, put up in 1964, and a memorial with an alabaster figure from 1912, yet neither is as touching as the simple stone to poor Edmund in the floor of the choir. I was fascinated by the medieval roof bosses, preserved at the rear of the nave since the Victorians replaced the wooden roof with stone. If Shakespeare had raised his bald pate during a service here, his eye might have caught sight of the appealingly grotesque imagery of these spirited medieval carvings. Most striking is Judas being devoured by Satan, with only a pair of legs protruding from the Devil’s hungry mouth, though I also like the sad face of the old king with icicles for a beard.

Crossing the river again, I looked out for the cormorants that I delight to see as one of the living remnants of Shakespeare’s London, which he saw when he walked out from the theatre onto the river bank, and wrote of so often, employing these agile creatures that can swallow fish whole as as eloquent metaphors of all-consuming Time. My destination was St Giles Cripplegate, where Edmund’s sons who did not live beyond infancy were baptised and William Shakespeare was the witness. Marooned at the centre of the Barbican today like a galleon shipwrecked upon a beach, I did not linger long here because most of the cargo of history this church carried was swept overboard in a fire storm in nineteen forty, when it was bombed and then later rebuilt from a shell. Just as in that searching game where someone advises you if you are getting warmer, I began to feel my trail had started warm but was turning cold.

Yet, resolutely, I walked on through St John’s Gate in Clerkenwell where Shakespeare once brought the manuscripts of his plays for the approval by the Lord Chamberlain before they could be performed. And, from there, I directed my feet along the Strand to the Middle Temple, where, in one of my favourite corners of the city, there is a sense – as you step through the gates – of entering an earlier London, comprised of small squares and alleys arched over by old buildings. Here in Fountain Court, where venerable Mulberry trees supported by iron props surround the pool, stands the magnificent Middle Temple Hall where the first performance of “Twelfth Night” took place in 1602, with Shakespeare playing in the acting company. At last, I had a building where I could be certain that Shakespeare had been present – but it was closed.

I sat in the shade by the fountain and took stock, and questioned my own sentiment now my feet were weary. Yet I could not leave, my curiosity would not let me. Summoning my courage, I walked past all the signs, until I came to the porter’s lodge and asked the gentleman politely if I might see the hall. He stood up, introducing himself as John and assented with a smile, graciously leading me from the sunlight into the cavernous hundred-foot-long hall, with its great black double hammer-beam roof, like the hand of God with its fingers outstretched or the darkest stormcloud lowering overhead. It was overwhelming.

“You see this table,” said John, pointing to an old dining table at the centre of the hall, “We call this the ‘cup board’ and the top of it is made of the hatch from Sir Francis Drake’s ship ‘The Golden Hind’ that circumnavigated the globe” And then, before I could venture a comment, he continued, “You see that long table at the end – the one that’s the width of the room, twenty-nine feet long – that’s made from a single oak tree which was a gift from Elizabeth I, it was cut at Windsor Great Park, floated down the Thames and constructed in this hall while it was being built. It has never left this room.”

And then John left me alone in the finest Elizabethan hall in Britain. Looking back at the great carved screen, I realised this had served as the backdrop to the performance of ‘”Twelfth Night” and the gallery above was where the musicians played at the opening when Orsino says, “If music be the food of love, play on.” The hall was charged and resonant. Occasioned by the clouds outside, sunlight moved in dappled patterns across the floor from the tall windows above.

I walked back behind the screen where the actors, including Shakespeare, waited, and I walked again into the hall, absorbing the wonder of the scene, emphasised by the extraordinary intricate roof that appeared to defy gravity. It was a place for public display and the show of power, but its elegant proportion and fine detail also permitted it to be a place for quiet focus and poetry. I sat on my own at the head of the twenty-nine foot long table in the only surviving building where one of William Shakespeare’s plays was done in his lifetime, and it was a marvel. I could imagine him there.

Judas swallowed by Satan

An old king at Southwark

St Giles Cripplegate where Edmund’s sons were baptised and William Shakespeare was the witness.

St John’s Gate where William Shakespeare brought the manuscripts of his plays to the Lord Chamberlain’s office to seek approval.

The Middle Temple Hall where “Twelfth Night” was first performed in 1602.

The twenty-nine foot long table made from a single oak from Windsor Great Park.

The wooden screen that served as the backdrop to the first production of” Twelfth Night.”

You may like to read these:

At Shakespeare’s First Theatre

The Door to Shakespeare’s London

A Few Of Hackney Mosaic Project’s Greatest Hits

We have two weeks left of our crowdfund to raise the money to publish a book of Tessa Hunkin’s Hackney Mosaic Project but we still have quite a way to go to reach our target.

So I thought I would publish a gallery of a few of the Project’s greatest hits today to give you a sense of the scale and scope of their achievement, creating so many wonderful mosaics that only a book can do justice to them all.

Click here to learn more and contribute

Please search in the pockets of your old coats and down the back of the sofa to see if you can find something you can contribute if you have not done so already. If you have any wealthy aunts or uncles who might like to support our project, please forward this post to them.

We have received some wonderful messages of support recently.

‘I am donating because I would love to own this book. It needs to be published. Robin from California’ – Robin Whitney

‘I hope the necessary money is raised. The mosaics of the Hackney Mosaic Project are fabulous.’ – Penny Tunbridge

‘The Hackney Mosaics are the most uplifting example of civic art I have seen this century.’ – Michael Zilkha

‘Another beautiful project, on the ground, and in print!’ – Iain Boyd

‘Congratulations for putting this together. It’s going to be an amazing book.’ – Helen Miles

‘What a wonderful initiative to celebrate and share the brilliant Hackney Mosaics.’ – Penelope Thompson

‘Very happy to support this great project’ – Mary Winch

‘Love this project, can’t wait to see it come to life. Every Gentle Author project is wonderful.’ – Frances Mayhew

Pavement at Shepherdess Walk

Shepherdess Walk

Shepherdess Walk

Shepherdess Walk

Somerford Estate

Somerford Estate

Acton Estate, Haggerston

Packington Estate, Islington

Tower Court Estate, Clapton

Tower Court Estate, Clapton

Tower Court Estate, Clapton

Tower Court Estate, Clapton

Tower Court Estate, Clapton

Hoxton Varieties, Pitfield St

Heroes of the pandemic, Linscott Rd

Butterfield Green

Private garden commission

Private garden commission

St Paul’s Churchyard, Hackney

St Paul’s Churchyard, Hackney

St Paul’s Churchyard, Hackney

Private garden commission, Hackney Downs

Hounds of Hackney Downs

Hounds of Hackney Downs

Playground Shelter, Hackney Downs

Playground Shelter, Hackney Downs

Playground Shelter, Hackney Downs

Grasmere Primary School

Click here to contribute to the publication of TESSA HUNKIN’S HACKNEY MOSAIC PROJECT

Hackney Mosaic Project At London Zoo

Tessa Hunkin works on her mosaic while lions prowl nearby

I accompanied Tessa Hunkin of Hackney Mosaic Project to the lions’ enclosure at London Zoo when she installed her masterpiece while big cats prowled around. Commissioned by the Zoological Society of London, the magnificent mosaic was the result of four months work involving around thirty people, with a core of fifteen experienced mosaicists, to create a centrepiece for the ‘Land of the Lions’ attraction at the Zoo.

The six panels of the mosaic portray the forest of Gir in Gujarat which is the origin of the lions at London Zoo. In Tessa’s design, Langur monkeys harvest fruit in the tree tops while Chital deer follow them below, scavenging windfalls and leftovers dropped from above. Yet this relationship serves a dual purpose for the Chital, since the Langurs see lions coming from far away, thereby warning the Chital when to take flight.

All through the winter months, the team at Hackney Mosaic worked in the pavilion on Hackney Downs, painstakingly glueing thousands of tiny tesserae to a large brown paper panel with Tessa’s design traced in reverse. Once this was complete, the panels were impressed onto a rendered wall at the zoo by Walter Bernardin, a mosaicist of lifelong experience, and the paper was removed to reveal the finished mosaic in all its glory, with the design the right way round.

It was a tense process, tearing away the backing paper without removing pieces of mosaic and then applying grouting. In fact, so all-consuming was this task that Tessa and Walter continued at their work without even noticing the lions prowling around in curiosity…

The team at Hackney Mosaic with the completed mosaic

Tessa’s final design

Photo composite of the work in progress, seen in reverse (click to enlarge)

The first panel installed at London Zoo

Mosaicist Walter Bernadin removes the backing paper and fixes the mosaic with grouting

The completed mosaic installed at London Zoo

You may also like to read about

The Mosaic Makers of Hackney Downs

Stitches In Time At St Anne’s, Limehouse

Back in 2011, it was my privilege to interview Di England, the founder of Stitches in Time. Although Di passed in 2017, her creations live on and the magnificent quilts are now the subject of a retrospective exhibition which opens today from 10-4pm at St Anne’s, Limehouse and runs each Friday and Saturday from 10-4pm until September.

This is my portrait of Di England of Stitches in Time taken in 2011 with a tapestry based on the Roque Map of East London, 1746. It is just one of hundreds of elaborate textile pieces, created collaboratively and involving over three thousand people, that she has supervised.

As a consequence, the former Assembly Room of Limehouse Town Hall – in the shadow of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s St Anne’s, Limehouse – was turned into a kind of giant sewing box with a million reels of thread and scraps of fabric are neatly organised in containers. There you could find everything you could need for the embroidery, appliqué, batik, printing, painting and weaving that was involved in the creation of textile masterpieces which tell the story of the East End through stitching. In these works, intricate details reveal the contribution of individuals while the overall conceptions were a devised collectively, requiring critical decisions about the nature of the social pictures that result.

Inspired by the trade union banners that were once housed there when the building was a museum of Labour history, Stitches in Time was involved with all kinds of groups across the East End to create pictorial histories of communities, devised as endeavours to bring people together in the practise of making.

In a rare moment of repose, I was able to sit down with Di in a quiet corner of the Assembly Room – surrounded by piles of textiles and sewing paraphernalia – while she spoke to me of her own background and how it all started.

“I was an ordinary girl from St Albans. I had signed up for Social Anthropology because I was interested in people and instead I discovered it was all about statistics. But when I went to St Albans Arts College, I rang up my mother and said, “I found the right thing, first time.” Yet although I wanted to be an artist, I couldn’t think of a way to relate it to everyday life. We were from Yorkshire originally, but my father died when I was very young and my mother came South to earn a living. She was a primary school teacher, an educationalist with a passionate belief in the expressive arts.

I trained in painting & sculpture at the Bristol & West of England Academy and at Chelsea College of Art. At Chelsea, the textiles department was next door and I responded to that. My grandmother was a seamstress and two of my aunts were dressmakers who rode motor bikes in the nineteen thirties. Even as a child, I would collect leaves to make dyes and I gathered boxes of textiles.

I worked as a teacher at Newham in the early seventies before I joined Freeform Arts, a community arts organisation in Dalston and I found it refreshing because it was all to do with making, putting art where it wasn’t removed from everyday life. The question we asked ourselves was how could you create things that had relevance for people in their daily lives. At first, the Arts Council said, “We will fund the roses but not the dandelions.” though gradually they accepted the idea that art could be created where people lived, in the workplace and in schools, and they started a community arts panel.

Stitches in Time had its origin in 1993, I was doing a project at Beatrice Tate School in Bethnal Green, designing a mosaic, looking at the legacy of the Huguenots in the area. And I thought, “What were they doing here?” I had just finished designing a mural in Carnaby St in Soho which also had Huguenots, and I realised that both locations were gates to the city. It made me appreciate what refugees have contributed. I thought, “What can I do that everyone can participate in?”

At that time, I was setting up a print workshop in the Spitalfields Market and we made tapestries there that were a cultural history of the East End told by its people. We hung them up in the market and discovered there was huge demand for tapestries as community projects. By 1999, we received funding to create this organisation, Stitches in Time, with a special emphasis on local history. We moved into Limehouse Town Hall in 2001 and the next year we became a registered charity.

Bonnard, Chagall and Ingres were my inspirations, when I was a painter, but I have found a different way to make paintings in textiles now.”

The Tower of London by Bluegate Fields Infants School & Mothers’ Group.

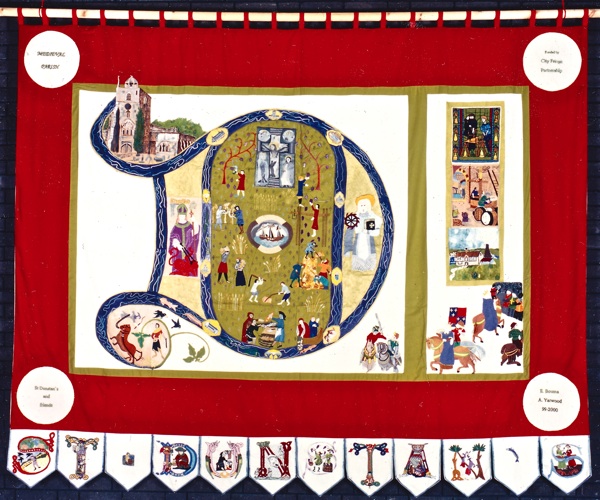

St Dunstan’s by Members of St Dunstan’s Parish, Stepney.

Life Cycle of the Silk Worm by Shapla Primary School & Mothers’ Group.

The Jacquard Loom by Bancroft Women’s Group.

Jewish Wedding by Kobi Nazrul Centre.

Petticoat Lane by Heba Women’s Project.

You may also like to read these other stories about textiles

At Stephen Walters & Sons, Silkweavers