Summer At Bow Cemetery

Next ticket availability Saturday 2nd September

At least once each Summer, I direct my steps eastwards from Spitalfields along the Mile End Rd towards Bow Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” created by act of Parliament in 1832 as the growing population of London overcrowded the small parish churchyards. Extending to twenty-seven acres and planned on an industrial scale, “The City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery” as it was formally called, opened in 1841 and within the first half century alone around a quarter of a million were buried here.

Although it is the tombstones and monuments that present a striking display today, most of the occupants of this cemetery were residents of the East End whose families could not afford a funeral or a plot. They were buried in mass public graves containing as many as forty bodies of random souls interred together for eternity. By the end of the nineteenth century the site was already overgrown, though burials continued until it was closed in 1966.

Where death once held dominion, nature has reclaimed the territory and a magnificent broadleaf forest has grown, bringing luxuriant growth that is alive with wildlife. Now the tombstones and monuments stand among leaf mould in deep woods, garlanded with ivy and surrounded by wildflowers. Tombstones and undergrowth make one of the most lyrical contrasts I can think of – there is a beautiful aesthetic manifest in the grim austerity of the stones ameliorated by vigorous plant life. But more than this, to see the symbols of death physically overwhelmed by extravagant new growth touches the human spirit. It is both humbling and uplifting at the same time. It is the triumph of life. Nature has returned and brought more than sixteen species of butterflies with her.

This is the emotive spectacle that leads me here, turning right at Mile End tube station and hurrying down Southern Grove, increasing my pace with rising expectation, until I walk through the cemetery gates and I am transported into the green world that awaits. At once, I turn right into Sanctuary Wood, stepping off the track to walk into a tall stand of ivy-clad sycamores, upon a carpet of leaves that is shaded by the forest canopy more than twenty metres overhead and illuminated by narrow shafts of sunlight descending. It is sublime. Come here to see the bluebells in Spring or the foxgloves in Summer. Come at any time of the year to find yourself in another landscape. Just like the forest in Richard Jefferies’ novel “After London,” the trees have regrown to remind us what this land was once like, long ago before our predecessors ever came here.

Over time, the tombstones have weathered and worn, and some have turned green, entirely harmonious with their overgrown environment, as if they sprouted and grew like toadstools. The natural stillness of the forest possesses greater resonance between cemetery walls and the deep green shadows of the woodland seem deeper too. There was almost no-one alive to be seen on the morning of my visit, apart from two police officers on horseback passing through, keeping the peace that is as deep as the grave.

Just as time mediates grief and grants us perspective, nature also encompasses the dead, enfolding them all, as it has done here in a green forest. These are the people who made East London, who laid the roads, built the houses and created the foundations of the city we inhabit. The countless thousands who were here before us, walking the streets we know, attending the same schools, even living in some of the same houses we live in today. The majority of those people are here now in Bow Cemetery. As you walk around, names catch your eye, Cornelius aged just two years, or Eliza or Louise or Emma, or Caleb who enjoyed a happy life, all over a hundred years ago. None ever dreamed a forest would grow over their head, where people would come to walk one day to discover their stones in a woodland glade. It is a vision of paradise above, fulfilled within the confines of the cemetery itself.

As I made my progress through the forest of tombstones, I heard a mysterious noise, a click-clack echoing through the trees. Then I came upon a clearing at the very heart of the cemetery and discovered the origin of the sound. It was a solitary juggler practicing his art among the graves, in a patch of sunlight. There is no purpose to juggling than that of delight, the attunement of human reflexes to create a joyful effect. It was a startling image to discover, and seeing it here in the deep woods – where so many fellow Londoners are buried – made my heart leap. In the vast wooded cemetery there was just me, the numberless dead and the juggler.

You may also like to read about

At Canvey Island

Click here to book for my tours through September and October

Inspired by a brochure given to me by Gary Arber, I decided to go for a day trip to Canvey Island. Printed by W.F.Arber & Co Ltd in the Roman Rd in the nineteen twenties – when Gary’s grandfather Walter ran the shop, his father (also Walter) was the compositor and uncles Len and Albert ran the presses – this brochure seduced me with its lyrical prose.

“Canvey Island, owing to its unique position at the meeting place of fresh and salt waters, which continually wash its shores, enjoys a nascent air which is extraordinarily health-giving and invigorating, and is, indeed in this respect, possibly above all other places in the kingdom. Prominent physicians in our leading hospitals pay tribute to the properties of the air, by sending patients to the Island in preference to any other locality.”

Yet in spite of this irresistible account of the Island’s charms, when I told people I was going to Canvey, they pulled long faces and declared, “You’re joking?” Undeterred by prejudice, I packed ham sandwiches in my satchel and set out from Fenchurch St Station with an open mind to discover Canvey Island for myself. Alighting at Benfleet, I crossed the River Ray to the Island arriving at the famous wall that reclaimed the land from the sea – constructed in the seventeenth century by three hundred dutch dyke diggers under the supervision of Cornelius Vermuyden.

“One of the first places the visitor will make for is the sea-wall, which he has undoubtedly heard a good deal about before coming to Canvey, and with which he will be anxious to make a closer acquaintance. The wall completely encircles the Island, and, following all its windings in and out, covers a distance of about eighteen miles.”

Since I had no map and had not been to Canvey before, Gary Arber’s brochure was my only guide. And so I set out along the wall where stonecrop and asters grew wild, buffered and blown by salt winds from the estuary. With a golf course to the landward side and salt marshes to the seaward side, that widened out into a vast open expanse stretching away towards Southend Pier on the horizon, it was an exhilarating prospect and I enjoyed the opportunity to fill my lungs with fresh sea air.

“The grand secret of the wonderful health-giving properties of the air is the evaporation from the “saltings,” during the time when the tides are out, which charges the air with ozone, which is thus constantly renewed and refreshed, making it extremely healthy, clean and bracing.”

Reaching Canvey Heights and looking back, the contrast between the hinterland crowded with bungalows and whimsical cottages, and the bare salt flats beyond the wall became vividly apparent. Many thousands before me, coming to escape from East London, had also been captivated by the Island romance that Canvey weaves – and I could understand their affection for this charmed Isle that proposes such a persuasive pastoral idyll, when resplendent beneath a sky of luminous blue.

“There is a charming freedom about life on Canvey which will appeal to most people whose work-a-day life has to be spent in towns or their suburbs. The change of scene is complete in every respect; streets, bricks and mortar, are replaced by bungalows of very varied designs and appearances”

Surrounding Canvey Heights, I found a neglected orchard of different varieties of plum trees all heavy with fruit, and filled my satchel with a selection of red, yellow and purple plums, before making my way to Rapkins Wharf with its magnificent old hulks nestled together in a forgotten creek. The Island breezes played upon the rigging like a wind harp, filling the boat yard with other-worldly music, where old sea salts sheltering amongst the array of rotting vessels. Next, turning the corner of the Island, I reached the shore facing the estuary and walking along the esplanade soon came to Concord Beach Paddling Pool where I joined the happy throng at the tea stall, spying the big ships that pass close by.

“All the vessels, bound to and from the large ports on the Thames, must pass Canvey, and thus a constant procession of all sizes can be watched with interest and pleasure, ploughing their lonely furrows through the waters. Monster ocean-going liners bound for the other side of the world, sailing vessels with their full rig of canvas spread, and, as the sun catches the sails, delighting the eye with one of the most haunting sights to be imagined – the estuary teems with interest at all times. Here one can realise that, despite the progress of motor and steam in water travel, there still remain a few ocean-going vessels under sail only.”

At the next table, a group of residents were debating the relative merits of Benidorm and Costa del Sol as holiday destinations, only to arrive at the startling yet prudent consensus that staying here in Canvey Island was best. Eavesdropping on their conversation, and observing the idiosyncratic villas adorned with pigeon lofts and flags, I recognised that an atmosphere of gleeful Island anarchy reigns in Canvey, situated at one remove from mainland Britain.

“The strict conventions of dress and deportment so tiresomely observed in towns can be ignored here in Canvey, and the visitor casts off all artificial restraints, simply observing the ordinary rules of decency and respect towards others which his own courtesy will dictate.”

Crossing through the streets, marvelling at the varieties of bungalows, I came to the Canvey Island Rugby Club playing field at Tewkes Creek, where I sat upon a bench to rest and admire the egrets feeding in the creek, while men walked their bull terriers on the green. Tracing my path back along the wall towards Benfleet station, I discovered circles of field mushrooms and picked myself a bunch of the wild fennel that grows in abundance, imparting its fragrance to the breeze. Then I returned home on the train to Fenchurch St at six, pleasantly weary, sunburnt and windswept, with my mushrooms, plums and fennel in hand as trophies, enraptured by all the delights of Canvey.

“For the family there is no better spot than Canvey for holidays – the glorious, exhilarating air sends them home again pictures of health and happiness.”

I never saw Canvey Island’s petrochemical refineries, or what happens at night. I am prepared to countenance that Canvey has its dark side, but I was innocent of it. I am an unashamed day-tripper.

This boat is for sale, contact the owner at Rapkins Wharf, Canvey Island.

Mushrooms picked at Canvey

Plums and fennel from Canvey

The wall around Canvey Island

At Walton On The Naze

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

All this time, Walton on the Naze has been awaiting me, nestling like a forgotten jewel cast up on the Essex coast, and less than an hour and a half from Liverpool St Station.

Families with buckets and spades joined the train at every stop, as we made our way eastwards to the point where Essex crumbles into the North Sea at the rate of two metres a year. Yet all this erosion, while reminding us of the force of the mighty elements, also delivers a perfect sandy beach – the colour of Cheddar cheese – that is ideal for sand castles and digging. Stepping from the small train amongst the flurry of pushchairs and picnic bags, at once the sea air transports you and the hazy resort atmosphere enfolds you. Unable to contain yourself, you hurry through the sparse streets of peeling nineteenth century villas and shabby weather-boarded cottages to arrive at a rise overlooking Britain’s third longest pier, begun in 1830.

In spite of the majestic pier, this is a seaside resort on a domestic scale. You will not find any foreign tourists here because Walton on the Naze is a closely guarded secret, it is kept by the good people of Essex for their sole use. At Walton on the Naze everyone is local. You see Essex families running around as if they owned the place, playing upon the beach in flagrant carefree abandon, as if it were their own back yard – which, in a sense, it is.

This sense of ownership is manifest in the culture of the beach huts that line the seafront, layers deep, in higgledy-piggledy terraces receding from the shore. These little wooden sheds are ideal for everyone to indulge their play house and dolls’ house fantasies – painting them in fanciful colours, giving them names like “Ava Rest,” and furnishing the interiors with gas cookers and garish curtains. At the seaside, all are licenced to pursue the fulfilment of residual childhood yearning in harmless whimsy. The seaside offers a place charged with potent emotional memory that we can return to each Summer. It is not simply that people get nostalgic for seaside resorts, but that these seasonal towns become the location of nostalgia itself – because the sea never changes and we revisit our former selves when we come back to the beach.

Walton Pier curls to one side like a great tongue taking a greedy lick from an ocean of ice cream, and the beach curves away in a crooked smile that leads your eye to the “Naze,” or “nose” to give its modern spelling. This vast bulbous proboscis extends from the profile of Essex as if from a patient in need of plastic surgery, provided in the form of relentless abrasion from the sea.

With so many attractions, the first thing to do is to sit down at the tables upon the beach outside Sunray’s Kiosk which serves the best fish & chips in Walton on the Naze. Every single order is battered and cooked separately in this tiny establishment, that also sells paper flags for sandcastles and shrimping nets and all essential beach paraphernalia. From here a path leads past a long parade of beach huts permitting you the opportunity to spy upon these domestic theatres, each with their proud owners lounging outside while their children run back and forth, vacillating between their haven of security and the irresistible wonder of the waves crashing at the shoreline.

Here I joined some girls, excitedly fishing for crabs with hooks and lines off a small jetty. They all screamed when one pulled out a much larger specimen than the tiddlers they had in their buckets, only to be reassured by the woman who was overseeing their endeavour. “Don’t be frightened – it’s just the Mummy!” she declared with a wicked smile, as she held up the struggling creature by a claw. From this jetty, I could see the eighty foot tower built upon the Naze in 1720 as a marker for ships entering the port of Harwich and after a gentle climb up a cliff path, and a strenuous ascent up a spiral staircase, I reached the top. Like a fly perched upon the nose of Essex, I could look North across the estuary of the Orwell towards Suffolk on the far shore and South to the Thames estuary with Kent beyond – while inland I could see the maze of inlets, appealingly known as the Twizzle.

I was blessed with a clear day of sunshine for my holiday. And I returned to the narrow streets of Spitalfields for another year with my skin flushed and buffeted by the elements – grateful to have experienced again the thrall of the shoreline, where the land runs out and the great ocean begins.

Sunray’s Kiosk on the beach, for the best fish & chips in Walton on the Naze.

“On this promontory is a new sea mark, erected by the Trinity-House men, and at the publick expence, being a round brick tower, near eighty foot high. The sea gains so much upon the land here, by the continual winds at S.W. that within the memory of some of the inhabitants there, they have lost above thirty acres of land in one place.” Daniel Defoe, 1722

My Pub Crawl From Smithfield To Holborn

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

What could be a nicer way to spend a lazy late summer afternoon than slouching around the pubs of Smithfield, Newgate, Holborn and Bloomsbury?

The Hand & Shears, Middle St, Clothfair, Smithfield

The Hand & Shears – They claim that the term ‘On The Wagon’ originated here – this pub was used for a last drink when condemned men were brought on a wagon on their way to Newgate Prison to be hanged – if the landlord asked ,“Do you want another?” the reply was “No, I’m on the wagon” as the rule was one drink only.

The Rising Sun – reputedly the haunt of body-snatchers selling cadavers to St Bart’s Hospital

The Rising Sun and St Bartholomew, Smithfield.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate St– the last surviving example of a Victorian Gin Palace, it is notorious for poltergeist activity apparently.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

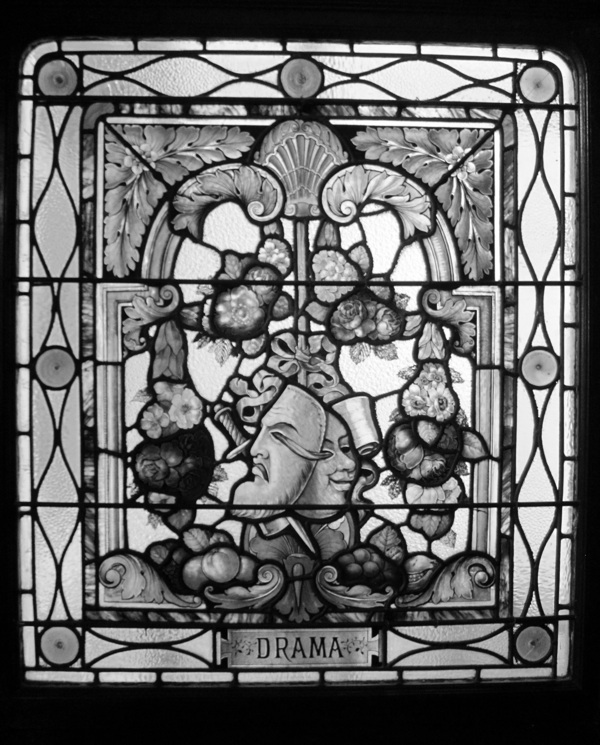

Princess Louise, High Holborn – interior of 1891 by Arthur Chitty with tiles by W. B. Simpson & Sons and glass by R. Morris & Son

Window at the Princess Louise, Holborn

Princess Louise

Princess Louise

Cittie of Yorke, High Holborn

The Lamb, Lamb’s Conduit St, Bloomsbury – built in the seventeen-twenties and named after William Lamb who erected a water conduit in the street in 1577. Charles Dickens visited, and Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath came here.

The Lamb

The Lamb

You may also like to look at

David Truzzi-Franconi’s East End

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

Photographer David Truzzi-Franconi sent me these pictures that he took in the seventies.

“While I was working in the City of London as an heraldic artist & calligrapher, I discovered on my lunchtime walks that a few paces from the bustle of Bishopsgate led me to another world. I combine a love of the drawing and writing of Geoffrey Fletcher with the photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Eventually I bought a Rolleiflex camera and spent my days off exploring the East End with a few rolls of film in my pocket. ” – David Truzzi-Franconi

Derelict House in Bethnal Green

Gunthorpe St, Whitechapel

Shop, E1

Chicksand St, E1

Derelict House, Spitalfields

Knife Grinder, Wilkes St, E1

Street performers at Tower Hill

Three legged dog

Meths drinkers on a bomb site near Brick Lane

Meths Drinkers at the Peabody Buildings

Blending ‘Red Biddy’ – wine and methylated spirits

Blacksmith’s Arms, Isle of Dogs

Thames Foreshore at Low Tide

Three Mills Island, Bow

St Paul’s, Covent Garden

Photographs copyright © David Truzzi-Franconi

Inside The Model Of St Paul’s

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

Simon Carter, Keeper of Collections at St Paul’s

In a hidden chamber within the roof of St Paul’s sits Christopher Wren’s 1:25 model of the cathedral, looking for all the world like the largest jelly mould you ever saw. When Charles II examined it in the Chapter House of old St Paul’s, he was so captivated by Wren’s imagination as manifest in this visionary prototype that he awarded him the job of constructing the new cathedral.

More than three hundred years later, Wren’s model still works its magic upon the spectator, as I discovered last week when I was granted the rare privilege of climbing inside to glimpse the view that held the King spellbound. While there is an austere splendour to the exterior of the model, I discovered the interior contains a heart-stopping visual device which was surely the coup that persuaded Charles II of Wren’s genius.

Yet when I entered the chamber in the triforium at St Paul’s to view the vast wooden model, I had no idea of the surprise that awaited me inside. Almost all the paint has gone from the exterior now, giving the dark wooden model the look of an absurdly-outsized piece of furniture but, originally, it was stone-coloured with a grey roof to represent the lead.

At once, you are aware of significant differences between this prototype and the cathedral that Wren built. To put it bluntly, the model looks like a dog’s dinner of pieces of Roman architecture, with a vast portico stuck on the front of the dome of St Peter’s in the manner of those neo-Georgian porches on Barratt Houses. Imagine a fervent hobbyist chopping up models of relics of classical antiquity and rearranging them, and this is the result. It is unlikely that this design would even have stood up if it had been built, so fanciful is the conception. Yet the long process of designing a viable structure, once he had been given instruction by Charles II, permitted Wren to reconcile all the architectural elements into the satisfying whole that we know today.

I had been tempted to visit the cathedral by an invitation to go inside the model but – studying it – I could not imagine how that could be possible. I could not see a way in. ‘Perhaps one end has hinges and Charles II crawled in on his hands and knees like a child entering a Wendy House?,‘ I was thinking, when Simon Carter, Keeper of Collections opened a door in the plinth and disappeared inside, gesturing me to follow. In blind faith, I dipped my head and walked inside.

When I stood up, I was beneath the dome with the floor of the cathedral at my chest height. There was just room for two people to stand together and I imagined the unexpected moment of intimacy between the Monarch and his architect, yet I believe Wren was quietly confident because he had a trick up his sleeve. From the inside, the drama of the architecture is palpable, with intersecting spaces leading off in different directions, and – as your eyes accustom to the gloom – you grow aware of the myriad refractions of light within this intricately-imagined interior.

Just as Wren directed Charles II, Simon Carter told me to walk to the far end of the model and sit on the bench placed there to bring my eye level down to the point of view of someone entering through the great west door. Then Simon left me there inside, just as I believe Wren left Charles II within the model, to appreciate the full effect.

I have no doubt the King was thrilled by this immersive experience, which quickly takes on a convincing reality of its own once you are alone. Charles II discovered himself confronted by a glorious vision of the future in which he was responsible for the first and greatest classically-designed church in this country, with the largest dome ever built. Such is the nature of the consciousness-filling reverie induced by sitting inside the model that the outside world recedes entirely.

How astonishing, once you have accustomed to the scale of the model, when a giant face appears filling the east window. I could not resist a gasp of wonder when I saw it and neither – I suggest – could Charles II when Christopher Wren’s smiling face appeared, grinning at him from the opposite end of the nave, apparently enlarged to twenty-five times its human scale.

In these unforgettable circumstances, the King could not avoid the realisation that Wren was a colossus among architects and – unquestionably – the man for the job of building the new St Paul’s Cathedral. The model worked its spell.

Behold, the largest jelly mould in the world!

The belfry that was never built

The single portico that was replaced by a two storey version

Just a few fragments of paintwork remain upon the exterior

Original paintwork can be seen inside the model

Charles II’s point of view from inside the model

You may like to read my other stories of St Paul’s

Roland Collins, Artist

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

My portrait of Roland Collins

At ninety-seven years old, artist Roland Collins lived with his wife Connie in a converted sweetshop south of the river that he crammed with singular confections, both his own works and a lifetime’s collection of ill-considered trifles. Curious that I had come from Spitalfields to see him, Roland reached over to a cabinet and pulled out the relevant file of press cuttings, beginning with his clipping from the Telegraph entitled ‘The Romance of the Weavers,’ dated 1935.

“Some time in the forties, I had a job to design a lamp for a company at 37 Spital Sq” he revealed, as if he had just remembered something that happened last week,“They were clearing out the cellar and they said, ‘Would you like this big old table?’ so I took it to my studio in Percy St and had it there forty years, but I don’t think they ever produced my lamp. I followed that house for a while and I remember when it came up for sale at £70,000, but I didn’t have the money or I’d be living there now.”

As early as the thirties, Roland visited the East End in the footsteps of James McNeill Whistler, drawing the riverside, then, returning after the war, he followed the Hawksmoor churches to paint the scenes below. “I’ve always been interested in that area,” he admitted wistfully, “I remember one of my first excursions to see the French Synagogue in Fournier St.”

Of prodigious talent yet modest demeanour, Roland Collins was an artist who quietly followed his personal enthusiasms, especially in architecture and all aspects of London lore, creating a significant body of paintings while supporting himself as designer throughout his working life. “I was designing everything,” he assured me, searching his mind and seizing upon a random example, “I did record sleeves, I did the sleeve for Decca for the first Long-Playing record ever produced.”

From his painting accepted at the Royal Academy in 1937 at the age of nineteen, Roland’s pictures were distinguished by a bold use of colour and dramatic asymmetric compositions that revealed a strong sense of abstract design. Absorbing the diverse currents of British art in the mid-twentieth century, he refined his own distinctive style at his studio in Percy St – at the heart of the artistic and cultural milieu that defined Fitzrovia in the fifties. “I used to take my painting bag and stool, and go down to Bankside.” he recalled fondly, “It was a favourite place to paint, especially the Old Red Lion Brewery and the Shot Tower before it was pulled down for the Festival of Britain – they called it the ‘Shot Tower’ because they used to drop lead shot from the top into water at the bottom to harden them.”

Looking back over his nine decades, surrounded by the evidence of his achievements, Roland was not complacent about the long journey he had undertaken to reach his point of arrival – the glorious equilibrium of his life when I met him.

“I come from Kensal Rise and I was brought up through Maida Vale.” he told me, “On my father’s side, they were cheesemakers from Cambridgeshire and he came to London to work as a clerk for the Great Central Railway at Marylebone. Because I was good at Art at Kilburn Grammar School, I went to St Martin’s School of Art in the Charing Cross Rd studying life drawing, modelling, design and lettering. My father was always very supportive. Then I got a job in the studio at the London Press Exchange and I worked there for a number of years, until the war came along and spoiled everything.

I registered as a Conscientious Objector and was given light agricultural work, but I had a doubtful lung so nothing much materialised out of it. Back in London, I was doing a painting of the Nash terraces in Regent’s Park when a policeman came along and I was taken back to the station for questioning. I discovered that there were military people based in those terraces and they wanted to know why I was interested in it.

Eventually, my love of architecture led me to a studio at 29 Percy Studio where I painted for the next forty years, after work and at weekends. I freelanced for a while until I got a job at the Scientific Publicity Agency in Fleet St and that was the beginnings of my career in advertising, I obviously didn’t make much money and it was difficult work to like.”

Yet Roland never let go of his personal work and, once he retired, he devoted himself full-time to his painting, submitting regularly to group shows but reluctant to launch out into solo exhibitions – until reaching the age of ninety.

In the next two years, he enjoyed a sell-out show at a gallery in Sussex at Mascalls Gallery and an equally successful one in Cork St at Browse & Darby. Suddenly, after a lifetime of tenacious creativity, his long-awaited and well-deserved moment arrived, and I consider myself privileged to have witnessed the glorious apotheosis of Roland Collins.

Brushfield St, Spitalfields, 1951-60 (Courtesy of Museum of London)

Columbia Market, Columbia Rd (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St George in the East, Wapping, 1958 (Courtesy of Electric Egg)

Mechanical Path, Deptford (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

Fish Barrow, Canning Town (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St Michael Paternoster Royal, City of London (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St Anne’s, Limehouse (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St John, Wapping, 1938

St John, Wapping, 1938

Spark’s Yard, Limehouse

Images copyright © Estate of Roland Collins