My Pub Crawl From Smithfield To Holborn

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

What could be a nicer way to spend a lazy late summer afternoon than slouching around the pubs of Smithfield, Newgate, Holborn and Bloomsbury?

The Hand & Shears, Middle St, Clothfair, Smithfield

The Hand & Shears – They claim that the term ‘On The Wagon’ originated here – this pub was used for a last drink when condemned men were brought on a wagon on their way to Newgate Prison to be hanged – if the landlord asked ,“Do you want another?” the reply was “No, I’m on the wagon” as the rule was one drink only.

The Rising Sun – reputedly the haunt of body-snatchers selling cadavers to St Bart’s Hospital

The Rising Sun and St Bartholomew, Smithfield.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate St– the last surviving example of a Victorian Gin Palace, it is notorious for poltergeist activity apparently.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

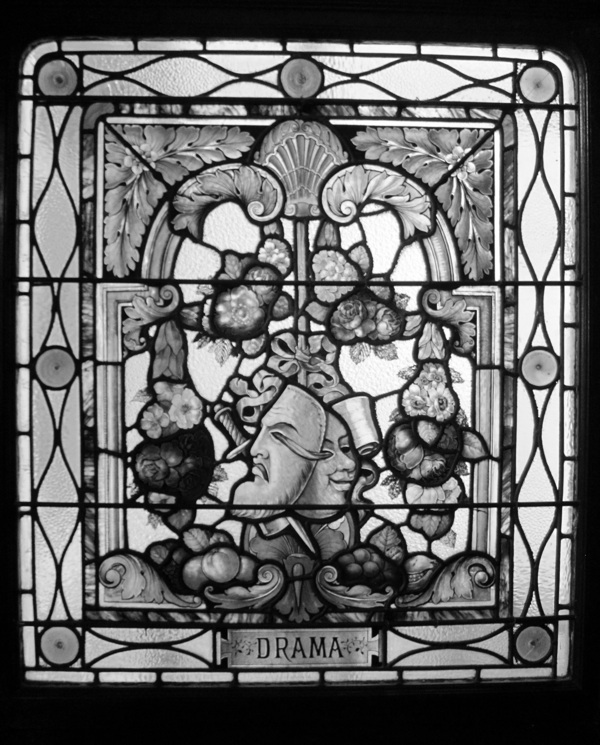

Princess Louise, High Holborn – interior of 1891 by Arthur Chitty with tiles by W. B. Simpson & Sons and glass by R. Morris & Son

Window at the Princess Louise, Holborn

Princess Louise

Princess Louise

Cittie of Yorke, High Holborn

The Lamb, Lamb’s Conduit St, Bloomsbury – built in the seventeen-twenties and named after William Lamb who erected a water conduit in the street in 1577. Charles Dickens visited, and Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath came here.

The Lamb

The Lamb

You may also like to look at

David Truzzi-Franconi’s East End

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

Photographer David Truzzi-Franconi sent me these pictures that he took in the seventies.

“While I was working in the City of London as an heraldic artist & calligrapher, I discovered on my lunchtime walks that a few paces from the bustle of Bishopsgate led me to another world. I combine a love of the drawing and writing of Geoffrey Fletcher with the photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Eventually I bought a Rolleiflex camera and spent my days off exploring the East End with a few rolls of film in my pocket. ” – David Truzzi-Franconi

Derelict House in Bethnal Green

Gunthorpe St, Whitechapel

Shop, E1

Chicksand St, E1

Derelict House, Spitalfields

Knife Grinder, Wilkes St, E1

Street performers at Tower Hill

Three legged dog

Meths drinkers on a bomb site near Brick Lane

Meths Drinkers at the Peabody Buildings

Blending ‘Red Biddy’ – wine and methylated spirits

Blacksmith’s Arms, Isle of Dogs

Thames Foreshore at Low Tide

Three Mills Island, Bow

St Paul’s, Covent Garden

Photographs copyright © David Truzzi-Franconi

Inside The Model Of St Paul’s

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

Simon Carter, Keeper of Collections at St Paul’s

In a hidden chamber within the roof of St Paul’s sits Christopher Wren’s 1:25 model of the cathedral, looking for all the world like the largest jelly mould you ever saw. When Charles II examined it in the Chapter House of old St Paul’s, he was so captivated by Wren’s imagination as manifest in this visionary prototype that he awarded him the job of constructing the new cathedral.

More than three hundred years later, Wren’s model still works its magic upon the spectator, as I discovered last week when I was granted the rare privilege of climbing inside to glimpse the view that held the King spellbound. While there is an austere splendour to the exterior of the model, I discovered the interior contains a heart-stopping visual device which was surely the coup that persuaded Charles II of Wren’s genius.

Yet when I entered the chamber in the triforium at St Paul’s to view the vast wooden model, I had no idea of the surprise that awaited me inside. Almost all the paint has gone from the exterior now, giving the dark wooden model the look of an absurdly-outsized piece of furniture but, originally, it was stone-coloured with a grey roof to represent the lead.

At once, you are aware of significant differences between this prototype and the cathedral that Wren built. To put it bluntly, the model looks like a dog’s dinner of pieces of Roman architecture, with a vast portico stuck on the front of the dome of St Peter’s in the manner of those neo-Georgian porches on Barratt Houses. Imagine a fervent hobbyist chopping up models of relics of classical antiquity and rearranging them, and this is the result. It is unlikely that this design would even have stood up if it had been built, so fanciful is the conception. Yet the long process of designing a viable structure, once he had been given instruction by Charles II, permitted Wren to reconcile all the architectural elements into the satisfying whole that we know today.

I had been tempted to visit the cathedral by an invitation to go inside the model but – studying it – I could not imagine how that could be possible. I could not see a way in. ‘Perhaps one end has hinges and Charles II crawled in on his hands and knees like a child entering a Wendy House?,‘ I was thinking, when Simon Carter, Keeper of Collections opened a door in the plinth and disappeared inside, gesturing me to follow. In blind faith, I dipped my head and walked inside.

When I stood up, I was beneath the dome with the floor of the cathedral at my chest height. There was just room for two people to stand together and I imagined the unexpected moment of intimacy between the Monarch and his architect, yet I believe Wren was quietly confident because he had a trick up his sleeve. From the inside, the drama of the architecture is palpable, with intersecting spaces leading off in different directions, and – as your eyes accustom to the gloom – you grow aware of the myriad refractions of light within this intricately-imagined interior.

Just as Wren directed Charles II, Simon Carter told me to walk to the far end of the model and sit on the bench placed there to bring my eye level down to the point of view of someone entering through the great west door. Then Simon left me there inside, just as I believe Wren left Charles II within the model, to appreciate the full effect.

I have no doubt the King was thrilled by this immersive experience, which quickly takes on a convincing reality of its own once you are alone. Charles II discovered himself confronted by a glorious vision of the future in which he was responsible for the first and greatest classically-designed church in this country, with the largest dome ever built. Such is the nature of the consciousness-filling reverie induced by sitting inside the model that the outside world recedes entirely.

How astonishing, once you have accustomed to the scale of the model, when a giant face appears filling the east window. I could not resist a gasp of wonder when I saw it and neither – I suggest – could Charles II when Christopher Wren’s smiling face appeared, grinning at him from the opposite end of the nave, apparently enlarged to twenty-five times its human scale.

In these unforgettable circumstances, the King could not avoid the realisation that Wren was a colossus among architects and – unquestionably – the man for the job of building the new St Paul’s Cathedral. The model worked its spell.

Behold, the largest jelly mould in the world!

The belfry that was never built

The single portico that was replaced by a two storey version

Just a few fragments of paintwork remain upon the exterior

Original paintwork can be seen inside the model

Charles II’s point of view from inside the model

You may like to read my other stories of St Paul’s

Roland Collins, Artist

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

My portrait of Roland Collins

At ninety-seven years old, artist Roland Collins lived with his wife Connie in a converted sweetshop south of the river that he crammed with singular confections, both his own works and a lifetime’s collection of ill-considered trifles. Curious that I had come from Spitalfields to see him, Roland reached over to a cabinet and pulled out the relevant file of press cuttings, beginning with his clipping from the Telegraph entitled ‘The Romance of the Weavers,’ dated 1935.

“Some time in the forties, I had a job to design a lamp for a company at 37 Spital Sq” he revealed, as if he had just remembered something that happened last week,“They were clearing out the cellar and they said, ‘Would you like this big old table?’ so I took it to my studio in Percy St and had it there forty years, but I don’t think they ever produced my lamp. I followed that house for a while and I remember when it came up for sale at £70,000, but I didn’t have the money or I’d be living there now.”

As early as the thirties, Roland visited the East End in the footsteps of James McNeill Whistler, drawing the riverside, then, returning after the war, he followed the Hawksmoor churches to paint the scenes below. “I’ve always been interested in that area,” he admitted wistfully, “I remember one of my first excursions to see the French Synagogue in Fournier St.”

Of prodigious talent yet modest demeanour, Roland Collins was an artist who quietly followed his personal enthusiasms, especially in architecture and all aspects of London lore, creating a significant body of paintings while supporting himself as designer throughout his working life. “I was designing everything,” he assured me, searching his mind and seizing upon a random example, “I did record sleeves, I did the sleeve for Decca for the first Long-Playing record ever produced.”

From his painting accepted at the Royal Academy in 1937 at the age of nineteen, Roland’s pictures were distinguished by a bold use of colour and dramatic asymmetric compositions that revealed a strong sense of abstract design. Absorbing the diverse currents of British art in the mid-twentieth century, he refined his own distinctive style at his studio in Percy St – at the heart of the artistic and cultural milieu that defined Fitzrovia in the fifties. “I used to take my painting bag and stool, and go down to Bankside.” he recalled fondly, “It was a favourite place to paint, especially the Old Red Lion Brewery and the Shot Tower before it was pulled down for the Festival of Britain – they called it the ‘Shot Tower’ because they used to drop lead shot from the top into water at the bottom to harden them.”

Looking back over his nine decades, surrounded by the evidence of his achievements, Roland was not complacent about the long journey he had undertaken to reach his point of arrival – the glorious equilibrium of his life when I met him.

“I come from Kensal Rise and I was brought up through Maida Vale.” he told me, “On my father’s side, they were cheesemakers from Cambridgeshire and he came to London to work as a clerk for the Great Central Railway at Marylebone. Because I was good at Art at Kilburn Grammar School, I went to St Martin’s School of Art in the Charing Cross Rd studying life drawing, modelling, design and lettering. My father was always very supportive. Then I got a job in the studio at the London Press Exchange and I worked there for a number of years, until the war came along and spoiled everything.

I registered as a Conscientious Objector and was given light agricultural work, but I had a doubtful lung so nothing much materialised out of it. Back in London, I was doing a painting of the Nash terraces in Regent’s Park when a policeman came along and I was taken back to the station for questioning. I discovered that there were military people based in those terraces and they wanted to know why I was interested in it.

Eventually, my love of architecture led me to a studio at 29 Percy Studio where I painted for the next forty years, after work and at weekends. I freelanced for a while until I got a job at the Scientific Publicity Agency in Fleet St and that was the beginnings of my career in advertising, I obviously didn’t make much money and it was difficult work to like.”

Yet Roland never let go of his personal work and, once he retired, he devoted himself full-time to his painting, submitting regularly to group shows but reluctant to launch out into solo exhibitions – until reaching the age of ninety.

In the next two years, he enjoyed a sell-out show at a gallery in Sussex at Mascalls Gallery and an equally successful one in Cork St at Browse & Darby. Suddenly, after a lifetime of tenacious creativity, his long-awaited and well-deserved moment arrived, and I consider myself privileged to have witnessed the glorious apotheosis of Roland Collins.

Brushfield St, Spitalfields, 1951-60 (Courtesy of Museum of London)

Columbia Market, Columbia Rd (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St George in the East, Wapping, 1958 (Courtesy of Electric Egg)

Mechanical Path, Deptford (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

Fish Barrow, Canning Town (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St Michael Paternoster Royal, City of London (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St Anne’s, Limehouse (Courtesy of Browse & Darby)

St John, Wapping, 1938

St John, Wapping, 1938

Spark’s Yard, Limehouse

Images copyright © Estate of Roland Collins

Click here to buy a copy of EAST END VERNACULAR

Tex Ajetunmobi, Photographer

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

Bandele Ajetunmobi – widely known as Tex – took photographs in the East End for almost half a century, starting in the late forties. He recorded a tender vision of interracial cameraderie, notably as manifest in a glamorous underground nightlife culture yet sometimes underscored with melancholy too – creating poignant portraits that witness an almost-forgotten era of recent history.

In 1947, at twenty-six years old, he stowed away on a boat from Nigeria – where he found himself an outcast on account of the disability he acquired from polio as a child – and in East London he discovered the freedom to pursue his life’s passion for photography, not for money or reputation but for the love of it.

He was one of Britain’s first black photographers and he lived here in Commercial St, Spitalfields, yet most of his work was destroyed when he died in 1994 and, if his niece had not rescued a couple of hundred negatives from a skip, we should have no evidence of his breathtaking talent.

Fortunately, Tex’s photographs found a home at Autograph ABP where they are preserved in the permanent archive and it was there I met with Victoria Loughran, who had the brave insight to appreciate the quality of her uncle’s work and make it her mission to achieve recognition for him posthumously.

“He was the youngest brother and he was disabled as well but he was very good at art, so they apprenticed him to a portrait photographer in Lagos. It suited him yet it wasn’t enough, so he packed up and, without anything much, left for England with my Uncle Chris.

Juliana, my mum had already come from Nigeria and, when I was born, she lived in Brick Lane but, after a gas explosion, we had to move out – that’s how we ended up in Newham. When I was a child, we didn’t come over here much – except sometimes to visit Brick Lane and Petticoat Lane on a Sunday – because we had moved to a better place. I understood I was born in Bethnal Green but I grew up in a better class of neighbourhood.

I knew that she didn’t approve of my uncle’s lifestyle, she didn’t approve of the drinking and probably there were drugs too. They were lots of rifts and falling out that I didn’t understand at the time. When everything became about having jobs to survive, she couldn’t comprehend doing something which didn’t make money. In another life, she might have understood his ideals – but we were immigrants and you have to feed yourself. She thought, ‘Why are you doing something that doesn’t sit comfortably with being poor?’

He did all this photography yet he didn’t do it to make money, he did it for pleasure and for artistic purposes. He was doing it for art’s sake.He had lots of books of photography and he studied it. He was doing it because those things needed to be recorded. You fall in love with a medium and that’s what happened to him. He spent all his money on photography. He had expensive cameras, Hasselblads and Leicas. My mother said, ‘If you sold one, you could make a visit to Nigeria.’ But he never went back, he was probably a bit of an outcast because of his polio as a child and it suited him to be somewhere people didn’t judge him for that.

He used to come and visit regularly when we lived in Stratford and there are family pictures that he took of us. His pictures pop out at me and remind me of my childhood, they prove to me that it really was that colourful. He was fun. Cissy was his girlfriend, they were together. She was white. When Cissy separated from her husband, he got custody of her children because she was with a black man – and her family stopped talking to her. She and Tex really wanted to have children of their own but they weren’t able to. They were Uncle Tex and Aunty Cissy, they would come round with presents and sweets, and they were a model couple to us as children. To see a mixed race couple wasn’t strange to us – where we lived it was full of immigrants and we were poor people and we just got on with life, and helped each other out.

He used to do buying and selling from a stall in Brick Lane. When he died, they found so much stuff in his flat, art equipment, pens, old records and fountain pens. He had a very good eye for things. Everybody knew him, he was always with his camera and they stopped him in the street and asked him to take their picture. He was able to take photographs in clubs, so he must have been a trusted and respected figure. Even if the subjects are poor, they are strutting their stuff for the camera. He gave them their pride and I like that.

He was not extreme in his vices. He died of a heart attack after being for a night out with his card-playing friends. He lived alone by then, he and Cissy were separated. But he was able to go to his neighbour’s flat and they called an ambulance so, although he lived alone, he didn’t die alone.

I thought he deserved more, that he was important. I just got bloody-minded. It wasn’t just because he was my uncle, it’s because it was brilliant photography. He deserved for people to see his work. There were thousands of pictures but only about three hundred have survived. Just one plastic bag of photos from a life’s work.”

Tex was generous with his photographs, giving away many pictures taken for friends and acquaintances in the East End – so if anybody knows of the existence of any more of his photos please get in touch so that we may extend the slim yet precious canon of Bandele “Tex” Ajetunmobi’s photography.

Whitechapel night club, nineteen-fifties

East End, nineteen seventies

On Brick Lane, seventies

Bandele “Tex” Ajetunmobi, self portrait

At Waltham Abbey

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

I cycled along the River Lea to Waltham Abbey. On my approach, even from the riverbank, I could see the majestic tower rising over the water meadows as the Abbey has done for the past thousand years, commanding the landscape and undiminished in visual authority.

Once you see it, you realise you are following in the footsteps of the innumerable credulous pilgrims who came here in hope of miraculous cures from the holy cross, which had reputedly relieved Harold Godwinson of a paralysis as a child before he became King Harold.

To the south of the Abbey church lies the market square, bordered with appealingly squint timber frame buildings punctuated by handsome eighteenth and nineteenth additions. Despite the proximity of the capital, the place still carries the air of an English market town.

Yet the great wonder is the Abbey itself, founded in the seventh century, built up by King Harold and destroyed by Henry VIII. Despite the ravages of time, the grandeur and scale of the Abbey is still evident in the precincts which have become a public park. Although the church that impresses today is less than half the size of what it was, it is enough to fire your imagination. An imposing stone gateway greets the visitor to the park where long, battered walls outline the former extent of the buildings. A tantalising fragment of twelfth century vaulting, which formerly served as the entrance to the cloisters, encourages the leap to conjure the cloisters themselves where now is merely an empty lawn. A walled garden filled with lavender and climbing roses draws you closest to the spirit of the place.

The outline of the former Abbey church is marked upon the grass and at the eastern end lies a surprise. A plain stone engraved with the words ‘Harold King of England Obit 1066,’ indicating this is where legend has it that he was laid to rest after the Battle of Hastings. I realised that maybe the remains of the man in the tapestry, killed by the arrow in the eye, lay beneath my feet. Coming upon his stone unexpectedly halted me in my tracks.

This was one of those startling moments when there is a possibility of history being real, something tangible, causing me to reflect upon the Norman Conquest. A thousand years ago, their power found its expression in the vast complex of buildings here, which were destroyed five hundred years ago as the expression of another power.

We too live in a time of dramatic transition, emerging from the shadow of the pandemic and accommodating to our country’s divorce from Europe. I cycled from Spitalfields to Waltham Abbey as a respite from the times, yet here I was confronting it in a mossy green churchyard. The equivocal consolation of the historical perspective is that it reminds us that empires rise and fall, but life goes on.

Effigy of King Harold

Harold cradles Waltham Abbey in his arm

The Lady Chapel

Victorian villa in the churchyard

The Welsh Harp

These vaults are all that is left of the twelfth century cloisters

Here lies Harold, the last Anglo Saxon King of England

Waltham Abbey

You may also like to read about

Hopping Portraits

Click here to book for my tours through August, September and October

When Tower Hamlets Community Housing staged a Hop Picking Festival down in Cable St, affording the hop pickers of yesteryear a chance to gather and share their tales of past adventures down in Kent, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I went along to join the party.

Connie Aedo – “I’m from Shovel Alley, Twine Court, at the Tower Bridge end of Cable St. I was very little when I first went hop picking. At weekends, when we worked half-days, my mum would let me go fishing. Even after I left school, I still went hop picking. Friends had cars and we drove down for the weekend, as you can see in the photo. Do you see the mirrors on the outside of the sheds? That’s because men can’t shave in the dark!”

Derek Protheroe, Terry Line, Charlie Protheroe, Connie Aedo and Terry Gardiner outside the huts at Jack Thompsett’s Farm, Fowle Hall, near Paddock Wood, 1967

Maggie Gardiner – “My mum took us all down to Kent for fruit picking and hop picking. Once, parachutes came down in the hop gardens and we didn’t know if they were ours or not, but they were Germans. So my mum told me and the others to go back to the hut and put the stew on. On the way back, a German aeroplane flew over and machine gunned us and we hid in a ditch until the man in the pub came to get us out. My mum used to say, ‘If you can fill an umbrella with hops, I’ll get you a bike,’ but I’m still waiting for it. We had some good times though and some laughs.”

Alifie Rains (centre) and Johnny Raines (right) from Parnham St, Limehouse, in the hop gardens at Jack Thompsett’s Farm, Fowle Hall, Kent

Vera Galley – “I was first taken hop picking as a baby. My mum, my nan and my brothers and sisters, we all went hop picking together. I never liked the smell of hops when I was working in the hop gardens because I had to put up with it, but now I love it because it brings back memories. ”

Mr & Mrs Gallagher with Kitty Adams and Jackie Gallgher froom Westport St, Stepney, in the hop gardens at Pembles Farm, Five Oak Green, Kent in 1950

Harry Mayhead – “I went hop picking when I was nine years old in 1935 and it was easy for kids. It was like going on holiday, getting a break from the city for a month. Where I lived in a block of flats and the only outlook was another block of flats, you never saw any green grass.”

Mr & Mrs Gallagher with their grandchildren at Pembles Farm, 1958

Lilian Penfold – ” I first went hop picking as a baby. I was born in August and by September I was down there in the hop garden. M daughter Julie, she was born in July and I took her down her down in September too. We were hopping until ten years ago when then brought in the machines and they didn’t need us any more. My aunt had grey hair but it turned green from the hops!”

The Liddiard family from Stepney in Kent, 1930

Dolly Frost – ” I was a babe in arms when they took me down to the hop gardens and I went picking for years and years until I was a teenager. I loved it while was I was growing up. My mother used to say, ‘Make sure you pick enough so you can have a coat and hat,’ and I got a red coat and matching red velour hat. As you can see, I like red.”

The Gallagher family from Stepney outside their huts at Pembles Farm, 1952

Charles Brownlow – “I started hop picking when I was seven. It was a working holiday to make some money. This was during the bombing, you woke up and the street had gone overnight, so to get to the country was an escape. You wouldn’t believe how many people crammed into those tiny huts. You took a jug of tea to work with you and at first it was hot but then it went cold but you carried on drinking it because you were hot. You could taste the hops in your sandwiches because it was all over your hands. There was a lot of camaraderie, people had nothing but it didn’t matter.”

Mr & Mrs Gallagher from Stepney at Pembles Farm

Margie Locke – “I’m eighty-eight and I went hop picking and fruit picking from the age of four months, and I only packed up last year because the farm I where went hop picking has been sold for development and they are building houses on it.”

At Highwood’s Farm, Collier St, Kent

Michael Tyrell – “I was first taken hop picking in the sixties when I was five months old, and I carried on until 1981 when hops was replaced by rapeseed which was subsidised by the European Community. In the past, one family was put in a single hut, eleven feet by eleven feet, but we had three joined together – with a bedroom, a kitchen with a cooker run off a calor gas bottle and even a television run off a car battery. There was still no running water and we had to use oil lamps. My family went to Thompsett’s Farm about three miles from Paddock Wood from the First World War onwards. I have a place there now, about a mile from where my grandad went hop picking. The huts are still there and we scattered my uncle’s ashes there.”

Annie & Bill Thomas near Cranbrook, Kent

Lilian Peat (also known as ‘Splinter’) – “My mum and dad and seven brothers and three sisters, we all went hop picking from Bethnal Green every year. I loved it, it was freedom and fresh air but we had to work. My mum used to get the tail end of the bine and, if we didn’t pick enough, she whipped us with it. My brothers used to go rabbiting with ferrets. The ferrets stayed in the hut with us and they stank. And every day we had rabbit stew, and I’ve never been able to eat rabbit since. We were high as kites all the time because the hop is related to the cannabis plant, that’s why we remember the happy times.”

John Doree, Alice Thomas, Celia Doree and Mavis Doree, near Cranbrook, Kent

Mary Flanagan – “I’m the hop queen. I twine the bines. I first went hop picking in 1940. My dad sent us down to Plog’s Hall Farm on the Isle of Grain. We went in April or May and my mum did the twining. Then we did fruit picking, then hop picking, then the cherries and bramleys until October. We had a Mission Hall down there, run by Miss Whitby, a church lady who showed us films of Jesus projected onto a sheet but, if the planes flew overhead, we ran back to our mothers. We used to hide from the school inspector, who caught us eventually and put us in Capel School when I was eight or ten – that’s why I’m such a dunce!”

Annie & Bill Thomas with Roy & Alf Baker, near Cranbrook, Kent

Portraits copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Archive photographs courtesy of Tower Hamlets Community Housing

You may also like to take a look at