The Last Of The London

As part of the Being Human Festival in November, Nadia Valman of Queen Mary University and projection artist Karen Crosby paid tribute to the former Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel by conjuring the ghosts of its past

Dorothy Stewart Russell, pioneer female medical student at the London and later the first female professor of Pathology in Western Europe

When it first rose in 1757 over farmland, market gardens and the hamlets east of the Tower, The London Hospital was an imposing presence. Its governors chose a design that would be sturdy and resilient, and the hospital turned its confident neoclassical frontage to the Whitechapel Rd with the promise of a bright and healthy future for the poor of East London. In the following decades, the docks, the sugar and brewing industries and the garment trade brought new employment to the area. By the late-nineteenth century, ‘The London’ served the most densely populated area of the metropolis and donations enabled it to become the largest general hospital in the country.

Yet today Whitechapel’s most monumental building looks vulnerable. On a chilly winter night, it slumps heavily in a pool of darkness, its façade covered with lesions, its brickwork blotchy. At the back of the hospital, pigeons roost on rusty balconies, and behind the boarded windows long corridors lie cold and inert. There is a grand melancholy that hangs over this derelict institution. We are witnessing not only the hubris of a structure built to last but also the husk of the labour, the hope, the striving, that once radiated within. Perhaps The London’s planners and makers knew that it must – in time – be superseded, but did the doctors and nurses who tended to those at the end of their lives ever imagine the dying of the building?

The Last of the London brought light back to the dark building in November. I worked with artist Karen Crosby to tell the stories of the hospital through photographs projected on its walls. Projected light is a magical and mysterious medium. Like hesitant ghosts, the images hover above the surfaces. You must look long and slow, and you cannot always be certain what you are seeing.

There are many well-known figures associated with The London, including Joseph Merrick, the so-called ‘Elephant Man,’ who was first discovered in 1884 being displayed in a disused shop in the Whitechapel Rd and later became a resident in the hospital. Also, Sir Frederick Treves, the surgeon who cared for him and Edith Cavell, who trained as a nurse at The London and was executed for helping British soldiers in German-occupied Belgium in 1915. Yet what interested us more were the untold stories of those who came from far and wide to work at The London, or whose lives began and ended there.

Karen Crosby is especially alert to what goes on in the background and edges of photographs, looking for the figures who were not the focus of the camera’s gaze. And so we found the ghosts of The London lurking in the corners of photographs or caught off guard in moments of uninhibited tenderness. There was something exceptionally moving about seeing these obscure individuals, whose lives are barely documented, transformed into giant luminous projections visible all the way along Whitechapel Rd. A maternity nurse gazes fondly at a newborn baby in the maternity ward, too preoccupied to pose for the camera. Two staff nurses in the back row of a group shot from 1895 look away from the lens because each is absorbed in her own world of reflection. In the photograph, they stand up straight as duty demanded but as we coax them from the shadows, the play of light and shade reveal their fatigue. They were working fourteen-hour days with two hours break and only one day off a month.

To reach their senior position, these women had to impress the Matron of The London, Eva Lückes. In the late nineteenth century, while still in her twenties, Lückes revolutionised training of nurses at the hospital and created a new perception of nursing as a respectable and rewarding profession. But she also believed it was a vocation that demanded constant exertion. ‘It is those who never willingly to give less than their best who will go on finding satisfaction in their chosen work,’ she wrote, ‘and who will discover that their powers have increased and that they are growing richer, not only in what they receive but in what they give. Of all things let us guard against slackness, against the performance of routine duties without that true “love of the work” which sanctifies the drudgery, that love which makes the labours of the day – or of the night – worthy of our best endeavours.’ These were high ideals for any woman but a nurse, said the Matron, was no ordinary woman.

It is because Eva Lückes examined each nurse’s sense of vocation with such rigour and kept such meticulous records of her observations that we can discover the complex individuals behind these enigmatic photographs. A young woman named Gertrude Harlow, for example, began as a probationer in 1885 with ‘average ability and a very abrupt manner’ but her training softened her manner and brought out her ‘earnest and unselfish character’, which gained the approval of Matron Lückes.

Rosamund Llewellyn, on the other hand, despite having a ‘hasty temper’ and being ‘naturally obstinate,’ excelled in charge of an isolation ward for septicaemia patients. Yet after a few years, she formed what the Matron described as an ‘exclusive’ and ‘morbid’ friendship with the sister on her ward – a euphemism for a same-sex relationship. Although the cornerstone of Lückes’ teaching was kindness and compassion for the patient, she regarded any personal emotional attachment on the part of a nurse as detrimental to her work. Finding Rosamund increasingly ‘indolent’ and ‘indifferent,’ she was evidently relieved when both nurses left the hospital in 1900, presumably for a life less determined by self-abnegation.

No such scrutiny was applied to the young men admitted as medical students at The London. We found some of them lounging hands in pockets in a leisurely manner in the background of a photograph of Cambridge Ward. They spent five years training: the first two attending lectures and demonstrations followed by three years on the job watching seniors on the hospital wards. It was a profession only open to the privileged and cost a fee of £100 (the equivalent of two years’ wages for an artisan or around £8000 in today’s currency). These young men would have felt comfortable in a large institution with a hierarchy reminiscent of school, but they were unaccustomed to the idea of providing services to people of a lower social class and sometimes got into trouble for treating patients without due courtesy.

Although the local neighbourhood was unfamiliar and thrilling territory, with music halls, gruesome waxwork shows, penny gaffs and all kinds of disreputable entertainment just outside the hospital gates, these distractions were discouraged for the more wholesome pleasures of playing in the hospital rugby team. In the photograph, they stand out in their smart dark jackets and waistcoats, but projected as translucent images onto the blackened brick wall it is harder for them to make their presence felt.

Perhaps the most uncanny aspect of hospital photographs is their stillness. A photograph of Crossman Ward gives a reassuring feeling of calm and order as we look straight down the middle of the room, with the beds arranged symmetrically on left and right and the nurses standing either side of the cabinet at the far end. The patients seem tiny on their heavy iron bedsteads bathed in light from windows that reach to the high ceiling. And yet such an image cannot tell us of the emotional experience of these individuals, their lives hanging in the balance, their bodies in pain. It cannot convey the intimacy of being vulnerable and being cared for. But when the photograph is projected on a decaying wall it absorbs the fragility of the building’s fabric. The peeling paint that cracks the surface of this otherwise clean, sharp image can help us see what the photograph tries to hide – the frail human bodies at the edges of the frame.

The London will not be fragile for long. It is now undergoing renovation and will be reborn as the civic centre for the Borough of Tower Hamlets. We hope that the preservation of many of the exterior and interior features that recall the building’s former life will serve as a memorial to those who played their part in the long history of public service in Whitechapel.

Two girls, 1906

Eva Lückes and staff nurses, 1895

Laying the foundation stone, 1864

Frederick Treves, Surgeon, 1892

Medical students, Cambridge Ward

Joseph Merrick

Nurse Annie Brewster, Head of the Ophthalmic Ward, was of Afro-Caribbean descent and spent her entire career at The London

Gertrude Harlow, Nurse at the London, 1885-89

Charles Jones, born in the Punjab, who enrolled as a medical student at the London in 1900 before his tragic death at the age of twenty

Nurse Rosamund Llewellyn, who enrolled as a probationer in 1886 and worked as a nurse for fourteen years

Crossman Ward

Images courtesy Barts Health Archives & Museums

Photographs of projections © Gary Schwartz

You can hear more of the history of The Royal London Hospital in I AM HUMAN, a free downloadable walking tour of the hospital written by Nadia Valman and produced by Natalie Steed

You may also like to take a look at

Spitalfields In Colour

Photographer Philip Marriage rediscovered these Kodachrome images recently, taken on 11th July 1984

Brushfield St

Crispin St

Widegate St

White’s Row

Artillery Passage

Brushfield St

Artillery Passage

Brushfield St

Fashion St

Widegate St

Artillery Passage

Gun St

Brushfield St

Gun St

Brushfield St

Parliament Court

Leyden St

Fort St

Commercial St

Brushfield St

Photographs copyright © Philip Marriage

You may also like to take a look at

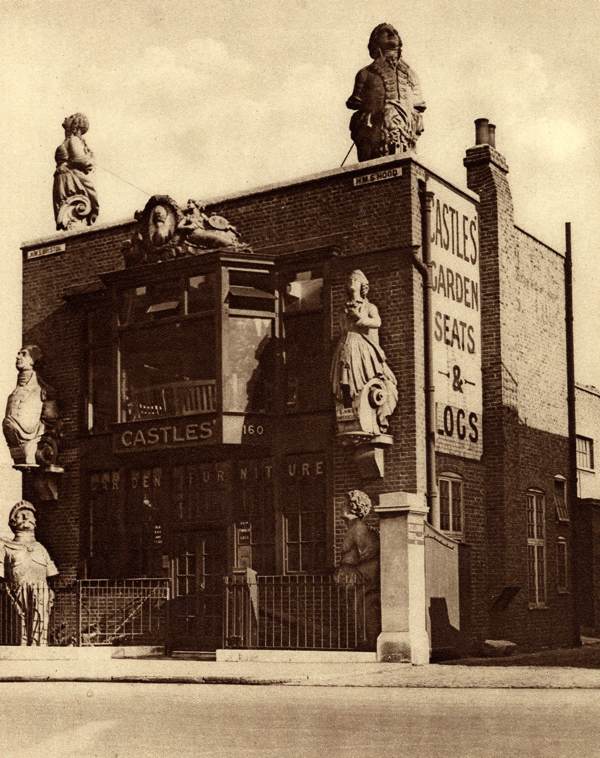

Jeffrey Johnson’s London Pubs

One day Jeffrey Johnson walked into the Bishopsgate Institute, deposited a stack of his splendid photographs with Archivist Stefan Dickers and left without another word. We can only conclude that these fond pictures from the seventies and eighties record the enigmatic Jeffrey’s favourite pubs. Some are familiar, but for the locations of the others – some of which are long gone – I call upon the superior experience of my readers.

Hoop & Grapes, Aldgate (Dentures Repaired)

Sir Walter Scott, Broadway Market

Knave of Clubs, Bethnal Green Rd

Dericote St, Broadway Market

Crown & Woolpack, St John St, Clerkenwell

Horn Tavern, Knightrider St, City of London (now known as The Centrepage)

Brunswick Arms, Upper Holloway

The Queen’s Head, City of London

The Queen’s Head, City of London

Unknown pub

The Crooked Billet, Walthamstow

Old Bell Tavern, St Pancras

Magpie & Stump, Old Bailey

The Mackworth Arms, Commercial Rd

Red Lion in Whitechapel Rd

Green Man

Green Man

Marquis of Anglesey, Ashmill St

The Crooked Billet

The Bull’s Head (Landlords fight to save City pub), Bishopsgate

The White Horse, Little Britain

The Olde Wine Shades, City of London

The Crispin, Finsbury Avenue

The Blue Posts, West India Dock Rd, Limehouse (Plasterer’s Required – Call at Back Door)

The Ticket Porter, Arthur St, City of London

Weavers Arms

Photographs copyright © Jeffrey Johnson

You may also like to take a look at

The Taverns of Long Forgotten London

Alex Pink’s East End Pubs Then & Now

The Gentle Author’s Next Pub Crawl

The Gentle Author’s Spitalfields Pub Crawl

The Gentle Author’s Dead Pubs Crawl

The Gentle Author’s Next Dead Pubs Crawl

Charlie Chaplin In Spitalfields

Somehow, it came as no surprise to discover that he had been here. I always thought of Charlie Chaplin as the one who carried a certain culture of the penniless, the ragged and the downtrodden from Europe across the Atlantic, translating it into an infinite capacity for hope, humour and resourcefulness in America. For centuries, Spitalfields has offered a refuge to the homeless and the dispossessed, so it makes sense that the most famous tramp of all time should have known this place.

Vivian Betts who grew up in The Primrose in Bishopsgate gave me handful of playbills that had been in the pub as long as she remembered and which she took with her when they left before the building was demolished in 1974. These bills were for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St. Opening in 1864, this vast two thousand seater theatre with a bar capacity of another thousand must have once presented a dramatic counterpoint to the church on the other side of the Spitalfields Market. Yet in the nineteenth century, it was one among many theatres in the immediate vicinity, in the days when the East End could match the West End for theatre and night life.

The ten-year-old Chaplin performed here as one of The Eight Lancashire Lads, a juvenile clog dance troupe, on Tuesday 24th October 1899 as part of the First Anniversary Benefit Performance, celebrating the reopening of the theatre a year earlier, after a fire that had destroyed it in 1896.

Before he died, Chaplin’s alcoholic father signed up his son at the age of eight, in November 1898, with his friend William Jackson who managed The Eight Lancashire Lads, in return for the boy’s board and lodgings and a payment of half a crown a week to Chaplin’s mother Hannah. The engagement took Chaplin away from his pitiful London childhood and from his mother who had struggled to support him and his elder brother Sydney on her own, existing at the edge of mental illness while moving the family in and out of a succession of rented rooms until her younger son ended up in the workhouse at seven.

“After practising for eight weeks, I was eligible to dance with the troupe. But now that I was past eight years old, I had lost my assurance and confronting the audience for the first time gave me stage fright. I could hardly move my legs. It was weeks before I could do a solo dance as the rest of them did.” Chaplin wrote of joining The Eight Lancashire Lads with whom he made his debut in Babes in the Wood, on Boxing Day 1898 at the Theatre Royal, Manchester.”My memory of this period goes in and out of focus,” he admitted later, “The outstanding impression was of a quagmire of miserable circumstances.”

Yet Chaplin’s experience touring Britain when Music Hall was at its peak of popularity proved both a great adventure and an unparalleled schooling in the method, technique and discipline that every performer requires to hold an audience. “Audiences like The Eight Lancashire Lads because, as Mr Jackson said, we were so unlike theatrical children. It was his boast that we never wore grease paint and our rosy cheeks were natural. If some of us looked a little pale before going on, he would tell us to pinch our cheeks,” Chaplin recalled,”But in London, after working two or three Music Halls a night, we would occasionally forget and look a little weary and bored as we stood on the stage, until we caught sight of Mr Jackson in the wings, grinning emphatically and pointing to his face, which had an electrifying effect of making us break into sparkling grins.”

The handbills that Vivian Betts gave me for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties date from 1900 and, significantly, one contains the announcement of Edisonograph Animated Pictures as part of the programme, advertising the new medium in which Chaplin was to become pre-eminent and that would eventually eclipse Music Hall itself.

As soon as he had mastered the dance act, Chaplin was impatient to move on to solo comedy. “I was not particularly enamoured with being just a clog dancer in a troupe of eight lads. Like the rest of them I was ambitious to do a single act, not only because it meant more money but because I instinctively felt it would be more gratifying than just dancing,” he wrote later of his precocious ten-year-old self, “I would like to have been a boy comedian – but that would have required nerve, to stand on the stage alone.”

It was in Whitechapel in the autumn of 1907 that the seventeen-year-old Chaplin made his solo comedy debut, at a Music Hall in the Cambridge Heath Rd. “I had obtained a trial week without pay at the Foresters’ Music Hall situated off the Mile End Rd in the centre of the Jewish quarter. My hopes and dreams depended on that trial week,” he declared. Yet the young Chaplin made a spectacular misjudgement. “At the time, Jewish comedians were all the rage in London, so I thought I would hide my youth under whiskers. I invested in musical arrangements for songs and funny dialogue taken from an American joke book, Madison’s Budget.” Chaplin was foolishly unaware that a Jewish satire might not play in the East End in front of a Jewish audience. “Although I was innocent of it, my comedy was most anti-Semitic and my jokes were not only old ones but very poor, like my Jewish accent.”

The disastrous consequences of Chaplin’s error in Whitechapel were to haunt him for the rest of his career. “After the first couple of jokes, the audience started throwing coins and orange peel and stamping their feet and booing. At first, I was not conscious of what was going on. Then the horror of it filtered into my mind. When I came off stage, I went straight to my dressing room, took off my make-up, left the theatre and never returned. I did my best to erase the night’s horror from my mind, but it left an indelible mark on my confidence,” he concluded in hindsight, conceding, “The ghastly experience taught me to see myself in a truer light.”

In 1908, Chaplin signed with Fred Karno’s comedy company in which he quickly became a rising star and, touring to America in 1913, he was talent spotted by the Keystone Film Studios and offered a contract at twenty-four years old for $150 a week. “What had happened? It seemed the world had suddenly changed, had taken me into its fond embrace and adopted me,” he wrote in astonishment and relief at his change of fortune in a life that had previously comprised only struggle.

Now I shall always think of the ten-year-old Chaplin when I walk down Commercial St, on his way to the Cambridge Theatre of Varieties, pinching his sallow cheeks to make a show of good cheer and with his whole life in motion pictures awaiting him.

At the northern end of Commercial St is the site of The Theatre, the first purpose-built theatre, where William Shakespeare performed and his early plays were staged. At the southern end of Commercial St is the site of the Goodman’s Fields Theatre, where David Garrick made his debut in Richard III and initiated the Shakespeare revival. And in middle was the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties, where Charlie Chaplin played. Most that pass down it may be unaware, yet the line of Commercial St traces a major trajectory through our culture.

Charlie Chaplin performed with The Eight Yorkshire Lads at the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St on Tuesday 24th October 1899

The Godfrey & Phillips cigarette factory replaced the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in 1936

The entrance of the Godfrey & Phillips building echoes the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties

Foresters Music Hall, 95 Cambridge Heath Rd – where Charlie Chaplin gave his disastrous first solo comedy performance in 1907 – demolished in 1965

My grateful thanks to David Robinson, Chaplin’s biographer, for his assistance with this article.

You may also like to read about

‘No Enemy But Winter & Rough Weather’

‘No enemy but winter and rough weather…’ As You Like It

Every year at this low ebb of the season, I go to Columbia Rd Market to buy potted bulbs and winter-flowering plants which I replant into my collection of old pots from the market and arrange upon the oak dresser, to observe their growth at close quarters and thereby gain solace and inspiration until my garden shows convincing signs of new life.

Each morning, I drag myself from bed – coughing and wheezing from winter chills – and stumble to the dresser in my pyjamas like one in a holy order paying due reverence to an altar. When the grey gloom of morning feels unremitting, the musky scent of hyacinth or the delicate fragrance of the cyclamen is a tonic to my system, tangible evidence that the season of green leaves and abundant flowers will return. When plant life is scarce, my flowers in pots that I bought for just a few pounds each at Columbia Rd acquire a magical allure for me, an enchanted quality confirmed by the speed of their growth in the warmth of the house, and I delight to have this collection of diverse varieties in dishes to wonder at, as if each one were a unique specimen from an exotic land.

And once they have flowered, I place these plants in a cold corner of the house until I can replant them in the garden. As a consequence, my clumps of Hellebores and Snowdrops are expanding every year and thus I get to enjoy my plants at least twice over – at first on the dresser and in subsequent years growing in my garden.

Staffordshire figure of Orlando from As You Like It

William Anthony, Last Of the Charlies

William Anthony 1789-1863

Behold the face of history! Photographed in 1863, the year of his death, but born in 1789, the year of the French Revolution, seventy-four-year-old William Anthony trudged the streets of Spitalfields and Norton Folgate through the darkest nights and thickest fogs for half a century, with his nose pointed into the wind and his jaw set in determination, successfully guided by a terrier-like instinct to seek out miscreants and prevent the outbreak of any unholy excesses of violence, such as erupted on the other side of the channel at the time of his nascence.

No wonder the Watch Book of Norton Folgate recorded an unbroken sequence of “All’s Well” for his entire tenure. No robbery was reported in fifty years. There was no nonsense with William Anthony. We need him at night on Brick Lane today.

The origin of the term ‘Charley’ for Watchman may originate in the time of Charles I when the monarch improved the watch system, although Jonathon Green, Spitalfields Life Contributing Lexicographer of Slang, who informed me of this possible derivation, can find no subsequent use in print for another one hundred and fifty years, when the term achieved currency in the early nineteenth century.

‘Charley’ as a derogatory term for a foolish person has survived into modern times, yet – as these photographs attest – William Anthony was unapologetic, quite content to be a ‘Charley.’ Behind him stand a long line of ‘Charlies’ stretching back through time for as long as London has existed and I think we may discern a certain dogged pride in William Anthony’s bearing, clutching his dark lantern in one hand and knobbly staff of office in the other, swaddled up in a great coat against the cold, wrapped in an apron against the filth, shod in sturdy boots against the damp and sheltered under his stout hat from the downpour.

Now I know his appearance, I will look out for William Anthony, lest our paths cross in the wintry dusk in Blossom St or Elder St – others might disregard him as another homeless old man walking all night but I shall hail him and pay my respects to the last of the ‘Charlies.’ He is the one of whom you could truly say you would be glad to meet him in a dark alley at night.

In Norton Folgate, the Watchman recorded an unbroken sequence of “All’s Well”

Tom & Jerry “getting the best of a Charley” at Temple Bar engraved by George Cruickshank, 1832

“Past one o’clock and a fine morning!” from Thomas Rowlandson’s ‘Lower Orders’

The Watchman, 1819 from ‘Pictures of Real Life for Children’

“Past Twelve O’Clock and A Cloudy Morning! & Patrol! Patrol!” from ‘Sam Syntax’s Cries of London’

“Past twelve o’clock and a misty morning! Past twelve o’clock and mind I give you warning!” published by Charles Hindley, Leadenhall Press, 1884

“Past twelve o’clock and a misty morning! Past twelve o’clock and mind I give you warning!” published by Charles Hindley, Leadenhall Press, 1884

Watchman by John Thomas Smith, copied from a print prefixed to ‘Villanies discovered by Lanthorne and Candlelight’ by Thomas Dekker 1616. “The marching Watch contained in number two thousand men, part of them being old souldiers, of skill to be captaines, lieutenants, serjeants, corporals &c. The poore men taking wages, besides that every one had a strawne hat, with no badge painted, and his breakfast in the morning.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Sights Of Wonderful London

It is my pleasure to publish these splendid pictures selected from the three volumes of Wonderful London edited by St John Adcock and produced by The Fleetway House in the nineteen-twenties. Not all the photographers were credited – though many were distinguished talents of the day, including East End photographer William Whiffin (1879-1957).

Roman galley discovered during the construction of County Hall in 1910

Liverpool St Station at nine o’clock six mornings a week

Bridge House in George Row, Bermondsey – constructed over a creek at Jacob’s Island

The Grapes at Limehouse

Wharves at London Bridge

Old houses in the Strand

The garden at the Bank of England that was lost in the reconstruction

In Huggin Lane between Victoria St and Lower Thames St by Andrew Paterson

Inigo Jones’ gate at Chiswick House at the time it was in use as a private mental hospital

Hoop & Grapes in Aldgate by Donald McLeish

Book stalls in the Farringdon Rd by Walter Benington

Figureheads of fighting ships in the Grosvenor Rd by William Whiffin

The London Stone by Donald McLeish

Dirty Dick’s in Bishopsgate

Poplar Almshouses by William Whiffin

Old signs in Lombard St by William Whiffin

Penny for the Guy!

Puddledock Blackfriars

Punch & Judy show at Putney

Eighteenth century houses at Borough Market by William Whiffin

A plane tree in Cheapside

Wapping Old Stairs by William Whiffin

Houndsditch Old Clothes Market by William Whiffin

Bunhill Fields

The Langbourne Club for women who work in the City of London

On the deck of a Thames Sailing Barge by Walter Benington

Piccadilly Circus in the eighteen-eighties

Leadenhall Poultry Market by Donald McLeish

London by Alfred Buckham, pioneer of aerial photography. Despite nine crashes he said, “If one’s right leg is tied to the seat with a scarf or a piece of rope, it is possible to work in perfect security.”

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at