The Dandy’s Perambulations

I am grateful to Sian Rees, student of my last blog course and author of PLANTING DIARIES, gardens, planting styles and their origins for kindly drawing my attention to The Dandy’s Perambulations by Robert Cruickshank, being an account of a trip to Kew Gardens in 1819

You may also like to take a look at

In The Orchards Of Kent

When the green shoots are sprouting and the leaves unfurling, who can resist an excursion to view the cherry blossom at the National Collection of Fruit Trees at Brogdale in Kent? This is the largest collection of fruit in the world – as the guides proudly remind you – with two hundred and eighty-five types of cherry among over two thousand varieties of fruit, including apples, pears, plums, currants, quinces and medlars.

As if this were not remarkable enough, I was informed that this particular corner of Kent – at the edge of Faversham – offers the very best conditions in the world for growing cherries. They may have originated in the forests of Central Asia, travelling east and west along the Silk Road before they were introduced by order of Henry VIII nearby at Sittingbourne, but here – I was assured – they have found their ultimate home.

The constitution of the soil in Kent is ideal for cherries and the temperate climate, in which the tender saplings are sheltered from the wind by long hedges of hornbeam, produces a delicacy of flavour in the ripe fruit which cannot by matched by the climactic extremes of the Mediterranean.

It was with these thoughts in mind that I advanced up the track, lined with decorative blossom in those livid pink tones so beloved of mid-twentieth century town planners, before turning the corner of a long hedge to confront the orchard of cherries. There are two specimens of each variety regimented in lines that stretch into the distance. The cherry trees are upon parade, awaiting your inspection and eager to display their flamboyant regalia.

You may also like to take a look at

A Pub Crawl In Smithfield & Holborn

What could be a nicer way to spend a lazy afternoon than slouching around the pubs of Smithfield, Newgate, Holborn and Bloomsbury?

The Hand & Shears, Middle St, Clothfair, Smithfield

The Hand & Shears – They claim that the term ‘On The Wagon’ originated here – this pub was used for a last drink when condemned men were brought on a wagon on their way to Newgate Prison to be hanged – if the landlord asked ,“Do you want another?” the reply was “No, I’m on the wagon” as the rule was one drink only.

The Rising Sun – reputedly the haunt of body-snatchers selling cadavers to St Bart’s Hospital

The Rising Sun and St Bartholomew, Smithfield.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate St– the last surviving example of a Victorian Gin Palace, it is notorious for poltergeist activity apparently.

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

The Viaduct Tavern, Newgate

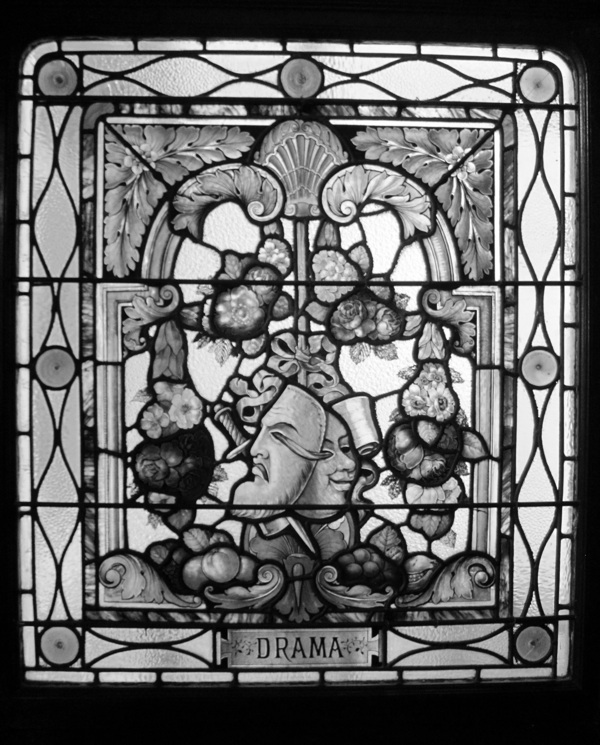

Princess Louise, High Holborn – interior of 1891 by Arthur Chitty with tiles by W. B. Simpson & Sons and glass by R. Morris & Son

Window at the Princess Louise, Holborn

Princess Louise

Princess Louise

Cittie of Yorke, High Holborn

The Lamb, Lamb’s Conduit St, Bloomsbury – built in the seventeen-twenties and named after William Lamb who erected a water conduit in the street in 1577. Charles Dickens visited, and Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath came here.

The Lamb

The Lamb

You may also like to look at

A Corner Shop In Old Ford Rd

I am delighted to publish this extract from A London Inheritance – a graduate of my blog writing course who is now celebrating five years of publishing posts online. The author inherited a series of old photographs of London from his father and by tracing them, he discovers the changes in the city over a generation. Follow A LONDON INHERITANCE, A Private History of a Public City

I am now taking bookings for the next courses, HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ on May 11th/12th and November 9th/10th. Come to Spitalfields and spend a weekend with me in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Fournier St, enjoy delicious lunches from Leila’s Cafe, eat cakes baked to historic recipes by Townhouse and learn how to write your own blog. Click here for details

If you are graduate of my course and you would like me to feature your blog, please drop me a line.

Fowlers Stores, 33 Old Ford Rd, 1986

I headed over to Bethnal Green to find a corner shop my father photographed in the Old Ford Rd in the eighties, when small, family-owned corner shops still catered for the day-to-day needs of Londoners.

His photograph shows a typical London corner shop. Shelves up against the window stocked with Mother’s Pride and a random assortment of household goods, always plenty of cigarette advertising, milk bottles in crates outside for collection, and an advert for Tudor Colour Films at the top of the door – a cheap film brand I tried once before returning to Kodak.

Today, what can be seen of the shop looks in poor condition, although I am surprised that the 33 Old Ford Rd sign is still there – all these years after my father’s photograph.

I would love to look behind the shutters and see how much of the original shop survives.

I am not sure when the shop closed. On the occasions I have walked down Old Ford Rd in recent years it has always been closed with the shutters down.

In my photograph, there is a National Lottery Instants sign above the door. I believe these were distributed when the National Lottery started scratchcard games in 1995, so the shop was still open in the middle of the nineties. On Google streetview, the shop was closed in all images from the first in July 2008, so Fowlers Stores must have closed between the mid-nineties and the two thousands.

The shop is located at the Bethnal Green end of Old Ford Rd, on the corner with Peel Grove. 33 Old Ford Rd is the last of a terrace of nineteenth century houses with shops below. I doubt if these buildings date from much before 1850 since an 1844 map does not show them. Old Ford Road originally terminated further to the east and this stretch appears to have been a combination of North St and Gretton St. Once, the North East London Cemetery was located just to the north where St John’s Church of England Primary School is now.

This has been a shop for most of the life of the building, well over a hundred and fifty years. In the 1891 Kelly’s London Post Office Directory, 33 Old Ford Rd is listed as being occupied by William Stone, Grocer. Given that the shop has now been closed for at least ten years, I am surprised it has not been converted for some other use. I wonder how long the remains of the shop at 33 Old Ford Rd will be there?

Photographs copyright © A London Inheritance

HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ: 11th-12th May & 9th-10th November 2019

Spend a weekend in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Spitalfields and learn how to write a blog with The Gentle Author.

This course will examine the essential questions which need to be addressed if you wish to write a blog that people will want to read.

“Like those writers in fourteenth century Florence who discovered the sonnet but did not quite know what to do with it, we are presented with the new literary medium of the blog – which has quickly become omnipresent, with many millions writing online. For my own part, I respect this nascent literary form by seeking to explore its own unique qualities and potential.” – The Gentle Author

COURSE STRUCTURE

1. How to find a voice – When you write, who are you writing to and what is your relationship with the reader?

2. How to find a subject – Why is it necessary to write and what do you have to tell?

3. How to find the form – What is the ideal manifestation of your material and how can a good structure give you momentum?

4. The relationship of pictures and words – Which comes first, the pictures or the words? Creating a dynamic relationship between your text and images.

5. How to write a pen portrait – Drawing on The Gentle Author’s experience, different strategies in transforming a conversation into an effective written evocation of a personality.

6. What a blog can do – A consideration of how telling stories on the internet can affect the temporal world.

SALIENT DETAILS

In 2019 courses will be held at 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields on 11th-12th May & 9th-10th November. Each course runs from 10am-5pm on Saturday and 11am-5pm on Sunday.

Lunch will be catered by Leila’s Cafe of Arnold Circus and tea, coffee & cakes by the Townhouse are included within the course fee of £300.

Accomodation at 5 Fournier St is available upon enquiry to Fiona Atkins fiona@townhousewindow.com

Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book a place on the course.

Jagmohan Bhakar, Rotarian

‘Sharing of food is very important in our culture’

When Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I visited Bow Food Bank last year, we were delighted to make the acquaintance of Jagmohan Bhakar who organises the supply of fresh fruit and vegetables donated each week by the Gurdwara in Campbell Rd. Jagmohan gets up before dawn each Monday to go the New Spitalfields Market in Leyton so that the food bank can offer the freshest produce.

Just a couple of weeks later, we encountered Jagmohan again. This time he was planting trees in Mile End Park on behalf of Tower Hamlets Rotary Club of which he is a keen member. So I asked Jagmohan if we might interview him and he kindly invited us both around for masala tea and prashad at his house in Bow.

When Jagmohan was late because he had been distributing complimentary bottles of water to runners in the City of London marathon, we realised that a certain pattern of behaviour was emerging. In becoming a Rotarian, Jagmohan has found the ideal vehicle to permit him the expression of his sense of generosity and service to others which is central to his Sikhism.

“I was born in Ambala in India and came here in 1967, when my father Dehal Singh Bhakar called my mother and me, my brother and two sisters to join him here. Since then I have lived in London. It was exciting to move to another world and be reunited with your family. My dad came in 1948 and it was quite some time since we had seen him. I was twelve years old and pleased to be with my family, I struggled to learn English. It was a new life of new experiences.

When my father came, he and some others worked as pedlars around Euston. They purchased textile goods near Liverpool St Station where there were Asian suppliers and sold them in different areas to make a living. At first he lived around Aldgate and Brick Lane, but by the time we arrived he was were living in 10 Piggott St in Limehouse. It was a big family home and a centre for many of our relatives, when they came to London it was their first stop. We all used to get together, and everybody loved seeing each other and going to each others’ houses.

School was difficult at that time in the sixties. I had a little bit of a language problem and also a difficulty in making any friends who were other peoples. It was a new experience. It was challenging, especially in the seventies after Enoch Powell made his speech. He was a bloody one. It was a sad time. People were very concerned. We were thinking of going back home. Some people left and came back later. Times were tough. At that time, many people from our community lived in Tower Hamlets in East London but because of the issues they started moving further out to Forest Gate and Manor Park. That was the reason they moved from Tower Hamlets to Newham.

I went to Langdon Park School in Poplar, there were only a few other pupils who were Sikhs. It was not bad. I am quiet by nature so I do not have many friends anyway. I had good days and bad days. We had no alternative because we had decided to make this our homeland, so we could not have second thoughts. Sometimes I had problems, walking down the road, there might be some abuse. I was beaten up a few times.

Over the years, things have changed. When I was seventeen years old, I left school and went to college. I studied Engineering but after that I could not find a job. Perhaps the course I had taken was too theoretical? I wanted a job in industry but they asked if I had any practical experience, which I did not. Times were hard. There were not many apprenticeships. I did some odd jobs.

My father was doing a little bit of business to keep himself, so I joined him after that, working in property lettings. Even the lettings were not that good at that time but we survived. I used to do the running around while he took the more relaxed role. It was not big business, just looking after the family really. But slowly things improved and it made life a little more comfortable. Today, me and my brother manage lettings for a few properties that my father left. We are doing much the same thing he did.

We are a very big family because my father had seven brothers and one sister. He was the youngest of his brothers. Obviously, they could not all stay in that house in Limehouse where my father lived with two of my uncles. Members of the family only stayed there until they could organise something for themselves. A year after we arrived in London, my father moved us here to Lyal Rd off Roman Rd where I still live today. I remember my brother buying toys from Gary Arber’s shop.

For the past seven years, I have been a member of the Rotary Club. I saw an advert in the Sunday Times and I have been with them from that time onwards. Sharing of food is very important in our culture. You always offer food when you greet anyone and we offer food to everyone at our gurdwaras. This custom of ‘lungar’ started with our first guru in the mid-fifteenth century. The idea was to eradicate the caste system, so everyone could sit and eat together on the same platform without hierarchy. Most people were desperate to be fed. It was sharing food and praying together under one roof so everybody felt in common with each other. ‘Love they neighbour and think of others as you are’ – anyone that follows these principles is a Sikh.”

Jagmohan delivers fresh vegetables weekly to Bow Food Bank on behalf of the Gurdwara in Campbell Rd

Jagmohan planting trees in Mile End Park on behalf of the Tower Hamlets Rotary Club

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

At Nichols Bros (Woodturners) Ltd

Geoff Nichols standing at his father Stanley’s lathe

‘We are the last proper woodturners in London,’ boasts Geoff Nichols of Nichols Bros (Woodturners) Ltd in Walthamstow. It sounds like quite a bold claim, but since I have learned the story of Geoff’s family endeavour stretching back over a century, examined their work and enjoyed a tour of the premises, I am more than happy to endorse Nichols Bros as ‘proper’ woodturners indeed.

An undistinguished single storey building in a side street gives no hint of the wonders within. For eighty years, the Nichols family have been woodturning at this location and proved themselves masters of the art and the craft. Passing through double green doors from the street, you turn directly left and discover yourself in another kingdom, filled with glowing golden timber and lined with wood chips.

In a long low-ceilinged brick room sit venerable lathes surrounded by stacks of new pine and off-cuts, while the walls are adorned with intricate examples of woodturning hanging like stalactites. Geoff Nichols and his trusty partner Harry Morrow have worked here for the past half century, and they step forward to greet you – looking the epitome of master craftsmen in their long blue twill coats.

Yet further delights await your gaze. Widening his eyes in excitement, Geoff leads you into the yard beyond where blue tarpaulins conceal a unique spectacle, accumulated in a series of old sheds. One after the other, he lifts the tarpaulins to reveal rooms filled with a seemingly infinite array of spindles, all meticulously organised by style and disappearing into the gloom like gothic grottos.

‘We have a collection in the region of three thousand different spindles,’ underestimates Geoff proudly, ‘We try to display as many as we can for ease of reference but we have lots more that are stored in boxes too.’

Unquestionably the largest collection in London and perhaps the largest collection in the world, this is – in effect – our national archive of stair spindles. It is a secret museum that tells the story of the growth of the capital in spindles – a cultural asset of the greatest significance and it will not come again. Perhaps most fascinating was the ‘London spindle’ – the most common design in the capital yet also the one with the most variants.

After half century of woodturning, Geoff Nichols needs to find someone to take on his astonishing legacy. Is there a craftworker reading this who would like to take this noble craft onwards for another fifty years and earn a lifetime’s income in the process? Is there an institution that can give a home to the largest collection of spindles in existence?

All these thoughts were buzzing in my mind as Geoff led me to the tiny cubby hole which serves as the office, where we competed over who should sit upon the only chair in the place, before I plonked myself down upon a trestle and he told me the full story of Nichols Bros.

“My dad Stanley Nichols and his brother Arthur started on this site in Walthamstow in 1949. They were two youngest out of five brothers, the two eldest – there was about a twenty year age difference – already had a woodturning business, Nichols & Nichols, in the Kingsland Rd in Shoreditch which they started before the First World War.

After Stanley and Arthur left school, they went to work for their elder brothers until the Second World War began, then they went off to the forces. After the war, they carried on with their elder brothers for a year or so before they decided to set up their own woodturning business here, Nichols Bros.

I came into it the day I left school at fifteen, that was fifty years ago now in 1969, and Harry joined about four or five years after me. My Uncle Arthur retired about five years after I started, he used to handle the paperwork, so Harry took over from him. I was more involved in the practical side of the business, especially hand woodturning.

We probably had about five or six employees at our peak which was about twenty years ago. Since then the trade has changed quite dramatically because the trend has moved away from wood towards glass and metal. In pubs in the East End, all the glass racks were made of turned wood spindles but that is no longer the case. Once upon a time, we made a lot of mangle rollers but obviously that is work we will never get asked to do again. We used to do a lot of table legs and when I first joined the business all we were really doing was standard lamps.

The furniture industry disappeared in the East End a quarter of a century ago and we are now tied in to the building trade. People spend a lot of money on their properties these days, adding rooms in the loft which needs staircases – newel posts, handrails and spindles. Spindles for staircases is the work we are asked to do now, although we still make the occasional four-poster bed and table legs for the furniture trade which does exist.

A lot of woodturning is imported from China but we cannot try to compete by producing volume, instead we do bespoke woodturning if a customer wants spindles or newel posts matched up. Skill is very important. When I first started working here, we used to get an influx of people asking if there was a job or could they learn the trade, but it seems the younger generation tend to shy away from manual trades today.

My dad was an exceptionally good woodturner, better at some things than me although I think I am better than him at others. You can be the most skilled woodturner in the world but you have to do it within a certain time, because time is money. It is all about earning a living, it is not a hobby. If you turn one spindle by hand, you have then got to be able to replicate it again quickly. Being able to get sharp definition in your work is very important. I can look at any piece of woodturning and tell straight away whether it was made by a highly skilled turner or not.

In woodturning, the trick is you must not pick up and tools and put them down again too many times. You have to do as much as you can with either the chisel or the gouge. When you change tools you are wasting time, so you must be able to do the maximum before you change tools. That is the secret to fast woodturning and to be able to turn nice bead, a fillet or a jug. The ridge around the shaft is called a ‘bead,’ like beading. The ridge between the bead and the shaft of the spindle is called the ‘fillet’ and it gives definition of the bead. The ‘jug’ is the wave profile, like on a jug. Any woodturning you see is beads, fillets, bands, hollows and jugs. That is all woodturning is.

It gives me pleasure to take a square blank and turn it into an artistic shape. You alone know the difficulty in turning it. You can see that you have made something that looks beautiful and will be there for a long time. When you visit old buildings, you appreciate the tremendous work that was involved in the woodturning, especially since they were working on primitive lathes compared to ours.

My children will not be coming into the business. My son works in the City and my daughter has an Estate Agents, so no-one in the family can take it over which is a real shame. I would be open to train someone if they came and asked me. It would be lovely if we could find someone who wanted to start a woodturning business, because over the last seventy years we have collected so many machines and tools which are irreplaceable.“

Geoff as a young man with his father Stanley Nichols

Stanley Nichols working at his lathe

Geoff at work on a barley-sugar twist spindle

Harry Morrow and Geoff Nichols at work at their lathes

Harry Morrow

The yard where the collection of more than three thousand spindles are kept

Some of the collection

Geoff Nichols

Multiple variants of the ‘London spindle’ – a distinctive style which evolved during the nineteenth century with the expansion of the capital

Nichols Bros (Woodturning) Ltd, 2A Milton Rd, Walthamstow, E17 4SR

You may also like to read about

In Old Paddington

At Paddington Green, Sarah Siddons calls upon a lifetime’s experience in the theatre to feign an appearance of interest despite her stultifyingly boring view of interminable traffic on the Westway. For years I saw her from the window of the bus and always intended to pay her a visit – a wish that I eventually fulfilled last week.

The green was once common land, formerly a place in its own right but now it has become somewhere the world passes by. Since the motorway sliced through in 1967, Paddington Green has been marooned, yet today offers a pleasing refuge from the urban chaos that surrounds it. John Plaw’s elegant church of 1791 sits upon a verdant mound enclosed by venerable magnolias, safeguarding the site where John Donne gave his first sermon, and William and Jane Hogarth were married.

Paddington was always a village defined by its position at the edge of the capital, but the escalation of change began with the arrival of the Grand Union Canal in 1801, accelerated by Brunel’s Great Western Railway in 1854. It is only a short walk from Paddington Green through the subway under the Westway and over the canal bridge to arrive at Paddington Station, but a journey through time spanning different worlds.

Paddington Station was where I first arrived in London on a school trip to be confronted with a full-scale riot in which police and football fans were charging at each other successively from either side of the station concourse. As a newcomer, I could only presume this was a normal state of affairs in the capital. It was an assumption confirmed when the rioters and their adversaries retreated obligingly, and the crowd parted like the Red Sea to permit our school party to walk through the middle with impunity, before resuming their conflict.

Over the years, the shabby streets around the station became familiar to me as it was my custom to walk from here into the centre of London to save the cost of a tube fare. Commonly, I underestimated the time it took to walk back from Marble Arch and had to run the last mile to Paddington, fearful of getting lost in the maze of small streets and missing my train home.

When I lived nearby in Bayswater, briefly in the early eighties, it was my delight to rise and walk through the streets in the middle of the night to view the drama of the mail trains being loaded with postal sacks and parcels of next day’s newspapers at Paddington. It was a different station then – a sooty black gothic cathedral in contrast to the luminous glasshouse it is now.

Nowadays I no longer have any family in the west and no reason to take the train from Paddington anymore. Although I have not been here in more than ten years, I was reassured how little the surrounding streets have changed – still lined with scruffy convenience stores, souvenir shops, cheap restaurants, massage parlours and sad hotels.

The grandeur of the tall white stucco terraces in Norfolk Sq comes as a surprise after the dingy atmosphere that prevails around the station but just another street later you come to the magnificent Sussex Gardens. On this visit, I realised that my notion of Paddington consists only of Praed St and its immediate environs – so authentically dirty old London, that the mould which became penicillin floated in a window here and gave the world antibiotics.

You may also like to take a look at