The Mysterious Stone Heads At Greenwich

Novelist Rosie Dastgir ruminates upon the significance of the old stone heads at Greenwich

In the Undercroft of Queen Anne’s Court at Sir Christopher Wren’s Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich lies a collection of stone heads from the early eighteenth century. Depicting Neptune, Galatea, and other denizens of the deep, they were intended for display upon the south elevation of the Painted Hall, but a decision by the architects to use brick instead of stone meant they were abandoned. For three centuries they have languished out of sight and remain hidden, tucked away in the shadow of the newly restored Painted Hall.

Last summer, I descended into the undercroft to visit the stone heads, in the company of artist Camilla Wilson who had been commissioned to paint them for an exhibition at the Old Royal Naval College. I found myself mesmerized and, gazing at their expressively wrought stone faces, wondering what their story might be. Lapidary worry is etched in their features and they are a little battered: a broken nose here, a chipped veil there, their quiet ruination a reminder of our ultimate return to dust. There is a quality of the old heads that is redolent of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot: anguish, bewilderment, a waiting for something that may never come to pass. They exude mystery yet appear to say something, a communication from a primordial time.

‘Omissions are not accidents’, wrote poet Marianne Moore, and I wanted to rescue the stone heads from the obscurity of their interment. I dug around for anything I could find about the carver who had sculpted them, Robert Jones of Stepney, and discovered little. He worked on Greenwich Hospital for Retired Seamen from the beginning of its construction until his death in 1722. He was paid for carving around fifty heads and was probably also responsible the ornate carvings on the Trinity Green Almshouses in Stepney. I found a ghostly facsimile of his will in the National Archives at Kew but its few more ragged details shone no light upon the carvers’ forgotten work.

The enigma of the heads exists in the patchy narrative of their origin and abandonment, and I sought a suitable idiom to capture their story. Sifting through a stack of eighteenth century chap books in the British Library, I became smitten by the rough hewn quality of these vibrant yarns and gossipy playlets embellished with simple woodcut prints. Cheaply made booklets that were sold on the street, they were published widely in England in the seventeenth and eighteen centuries. At the peak of their popularity, they sold in thousands, passed from hand to hand, and featured a trove of subjects from fairytales and folklore, to politics, crime and magic tricks. They offered a vital medium for the dissemination of popular culture and entertainment, a digest of unreliable history for the common people of England. Like social media, they were textual exchanges occupying the fragile space between truth and fiction, cheaply made and easily disseminated.

My version of an eighteenth century chap book, The Heads’ Lament, conjures an imaginary WhatsApp conversation among the old stone heads at a moment when our nation teeters on the cusp of instability. We have been here many times before – of course – yet it is worth noting the historical parallel with our own times in the early seventeen-hundreds, around the time the heads were carved. Sir James Thornhill had been commissioned to paint the Great Hall at the Royal Naval College to commemorate the tumultuous political moment when the United Kingdom was taking shape. Denizens of the deep, the old carved heads bear witness to the gyre of history, keeping watch over our islands’ waters and the people who cross them. Sidelined for centuries, they yearn to be seen.

Photos of the heads © Camilla Wilson

Chapbook photography © Sarah Ainslie

Rosie’s chapbook will be on sale at the exhibition

You may also like to take a look

Tony Bock At Watney Market

Tony Bock took these pictures of Watney Market while working as a photographer on the East London Advertiser between 1973 and 1978. Within living memory, there had been a thriving street market in Watney St, yet by the late seventies it was blighted by redevelopment and Tony recorded the last stalwarts trading amidst the ruins.

In the nineteenth century, Watney Market had been one of London’s largest markets, rivalling Petticoat Lane. By the turn of the century, there were two hundred stalls and one hundred shops, including an early branch of J.Sainsbury. Tony’s poignant photographs offer a timely reminder of the life of the market before the concrete precinct.

Born in Paddington yet brought up in Canada, Tony Bock came back to London after being thrown out of photography school and lived in the East End where his mother’s family originated, before returning to embark on a thirty-year career as a photojournalist at The Toronto Star. Recalling his sojourn in the East End and contemplating his candid portraits of the traders, Tony described the Watney Market he knew.

“I photographed the shopkeepers and market traders in Watney St in the final year, before the last of it was torn down. Joe the Grocer is shown sitting in his shop, which can be seen in a later photograph, being demolished.

In the late seventies, when Lyn – my wife to be – and I, were living in Wapping, Watney Market was our closest street market, just one stop away on the old East London Line. It was already clear that ‘the end was nigh,’ but there were still some stallholders hanging on. My memory is that there were maybe dozen old-timers, but I don’t think I ever counted.

The north end of Watney St had been demolished in the late sixties when a large redevelopment was promised. Yet, not only did it take longer to build than the Olympic Park in Stratford, but a massive tin fence had been erected around the site which cut off access to Commercial Rd. So foot and road traffic was down, as only those living nearby came to the market any more. The neighbourhood had always been closely tied to the river until 1969 when the shutting of the London Docks signalled the change that was coming.

The remaining buildings in Watney St were badly neglected and it was clear they had no future. Most of the flats above the shops were abandoned and there were derelict lots in the terrace which had been there since the blitz. The market stalls were mostly on the north side of what was then a half-abandoned railway viaduct. This was the old London & Blackwall Railway that would be reborn ten years later as the Docklands Light Railway and prompt the redevelopment we see today.

So the traders were trapped. The new shopping precinct had been under construction for years. But where could they go in the meantime? The new precinct would take several more years before it was ready and business on what was left of the street was fading.

Walking through Watney St last year, apart from a few stalls in the precinct, I could see little evidence there was once a great market there. In the seventies, there were a couple of pubs, The Old House At Home and The Lord Nelson, in the midst of the market. Today there are still a few old shops left on the Cable St end of Watney St, but the only remnant I could spot of the market I knew was the sign from The Old House At Home rendered onto the wall of an Asian grocer.

I remember one day Lyn came home, upset about a cat living on the market that had its whiskers cut off. I went straight back to Watney St and found the beautiful tortoiseshell cat hiding under a parked car. When I called her, she came to me without any hesitation and made herself right at home in our flat. Of course, she was pregnant, giving us five lovely kittens and we kept one of them, taking him to Toronto with us.”

Eileen Armstrong, trader in fruit and vegetables

Joe the Grocer

Gladys McGee, poet and member of the Basement Writers’ group, who wrote eloquently of her life in Wapping and Shadwell. Gladys was living around the corner from the market in Cable St at this time.

Joe the Grocer under demolition.

Frames from a contact sheet showing the new shopping precinct.

Photographs copyright © Tony Bock

You may like to see these other photographs by Tony Bock

George Gladwell’s Photos Of Columbia Rd

This is George Gladwell selling his Busy Lizzies from the back of a van at Columbia Rd in the early seventies, drawing the attention of bystanders to the quality of his plants and captivating his audience with a bold dramatic gesture of presentation worthy of Hamlet holding up a skull. George has been trading at the market since 1949 and it is my delight to publish this selection of his old photographs.

There is an air of informality about the flower market as it is portrayed in George’s pictures. The metal trolleys that all the traders use today are barely in evidence, instead plants are sold from trestle tables or directly off the ground – pitched as auctions – while seedlings come straight from the greenhouse in wooden trays, and customers carry away their bare-rooted plants wrapped in newspaper. Consequently, the atmosphere is of a smaller local market than we know today, with less stalls and just a crowd of people from the neighbourhood.

You can see the boarded-up furniture factories, that once defined Bethnal Green, and Ravenscroft Buildings, subsequently demolished to create Ravenscroft Park, both still in evidence in the background – and I hope sharp-eyed readers may also recognise a few traders who continue working in Columbia Rd Market today.

Over the years, many thousands of images have been taken of Columbia Rd Flower Market, but George Gladwell’s relaxed photographs are special because they capture the drama of the market seen through the eyes of an insider.

“I arrived in this lonely little street in the East End with only boarded-up shops in it at seven o’clock one Sunday morning in February 1949. And I went into Sadie’s Cafe where you could get a whopping great mug of cocoa, coffee or tea, and a thick slice of bread and dripping – real comfort food. Then I went out onto the street again at nine o’ clock, and a guy turned up with a horse and cart loaded with flowers, followed by a flatback lorry also loaded with plants.

At the time, I had a 1933 ambulance and I drove that around to join them, and we were the only three traders until someone else turned up with a costermonger’s barrow of cut flowers. There were a couple more horse and carts that joined us and, around eleven thirty, a few guys came along with baskets on their arms with a couple of dozen bunches of carnations to sell, which was their day’s work.

More traders began turning over up over the next few months until the market was full. There were no trolleys then, everything was on the floor. Years ago, it wasn’t what you call “instant gardening,” it was all old gardeners coming to buy plants to grow on to maturity. It was easy selling flowers then, though if you went out of season it was disappointing, but I never got discouraged – you just have to wait.

Mother’s Day was the beginning of the season and Derby Day was the finish, and it still applies today. The serious trading is between those two dates and the rest of the year is just ticking over. In June, it went dead until it picked up in September, then it got quite busy until Bonfire Night. And from the first week of December, you had Christmas Trees, holly and mistletoe, and the pot plant trade.

I had a nursery and I lived in Billericay, and I was already working in Romford, Chelmsford, Epping, Rochester, Maidstone and Watford Markets. A friend of mine – John – he didn’t have driving licence, so he asked me to drive him up on a Sunday, and each week I came up to Columbia Rd with him and I brought some of my own plants along too, because there was a space next to his pitch.

My first licenced pitch was across from the Royal Oak. I moved there in 1958, because John died and I inherited his pitches, but I let the other four go. In 1959, the shops began to unboard and people took them on here and there. That was around the time public interest picked up because formerly it was a secret little market. It became known through visitors to Petticoat Lane, they’d walk around and hear about it. It was never known as “Columbia Rd Flower Market” until I advertised it by that name.

It picked up even more in the nineteen sixties when the council introduced the rule that we had to come every four weeks or lose our licences, because then we had to trade continuously. In those days, we were all professional growers who relied upon the seasons at Columbia Rd. Although we used to buy from the Dutch, you had to have a licence and you were only allowed a certain amount, so that was marginal. It used to come by train – pot plants, shrubs and herbaceous plants. During the war, agriculture became food production, and fruit trees planted before the war had matured nicely. They sold masses of these at the Maidstone plant auctions and I could pick them up for next to nothing and sell them at Columbia Rd for two thousand per cent profit. Those were happy times!

In the depression at the end of the nineteen fifties, a lot of nurserymen sold their plots for building land because they couldn’t make it pay and it made the supply of plants quite scarce. So those of us who could grow our own did quite well but, although I did a mail order trade from my nursery, it wasn’t sufficient to make ends meet. Hobby traders joined the market then and they interfered with our trade because we were growers and kept our stock from week to week, but they would sell off all their stock cheap each week to get their money back. I took a job driving heavy haulage and got back for Saturday and Sunday. I had to do it because I had quite a big family, four children.

In the seventies, I was the first to use the metal trolleys that everyone uses now. My associates said I would never make it pay because I hocked myself up to do it. At the same time, plants were getting plastic containers, whereas before we used to sell bare roots which made for dirty pitches, so that was progress. All the time we were getting developments in different kinds of plants coming from abroad. You could trade in these and forget growing your own plants, but I never did.

Then in the nineties we had problems with rowdy traders and customers coming at four in the morning, which upset the residents and we were threatened with closure by the council. We had a committee and I was voted Chairman of the Association. We negotiated with the neighbours and agreed trading hours and parking for the market, so all were happy in the end.

It’s been quite happy and fulfilling, what I’ve finished up with is quite a nice property – something I always wanted. I like hard work, whether physical or mental. I used to sell plants at the side of the road when I was seven, and I used to work on farms helping with the milking at five in the morning before I went to school. I studied architecture and yet, as a job, I was never satisfied with it, I preferred the outdoor life and the physical part of it. Having a pitch is always interesting – it’s freedom as well.”

Albert Harnett

Colin Roberts

Albert Playle

Bert Shilling

Ernie Mokes

The magnificently named Carol Eden.

Fred Harnett, Senior

Herbie Burridge

George Burridge, Junior

Jim Burridge, Senior

Kenny Cramer

Lou Burridge

Robert Roper

Ray Frost

Robert Roper

George Burridge

George Gladwell today (Photograph by Jeremy Freedman)

Neville Turner Of Elder Street

This is Neville Turner sitting on the step of number seven Elder St, just as he used to when he was growing up in this house in the nineteen forties and fifties. Once upon a time, young Neville carved his name upon a brick on the left hand side of the door, but that has been removed and replaced now that these are prized houses of historic importance.

When Neville lived here, the landlords did no maintenance and the building was dilapidated. But Neville’s Uncle Arthur wallpapered the living room with attractive wisteria wallpaper, which became the background to the happy family life they all enjoyed, in the midst of the close-knit community in Elder St during the war and afterwards. Subsequently, the same wisteria wallpaper appeared as a symbol of decay, hanging off the wall, in photographs taken to illustrate the dereliction of Elder St when members of the Spitalfields Trust squatted it to save the eighteenth century houses from demolition.

It was only when an artist appeared – one Sunday morning in Neville’s childhood – sketching the pair of weaver’s houses at number five and seven, that Neville became aware that he was growing up in a dwelling of historic importance. Yet to this day, Neville protests he carries no sentiment about old houses. “This affection for the Dickensian past is no substitute for hot and cold running water,” he admitted to me frankly, explaining that the family had to go the bathhouse in Goulston St each week when he lived in Elder St.

However, in spite of his declaration, it soon became apparent that this building retains a deep personal significance for Neville on account of the emotional history it contains, as he revealed to me when he returned to Spitalfields this week.

“My parents moved from Lambeth into number seven Elder St in 1931 and lived there until they were rehoused in 1974. The roof leaked and the landlords let these houses fall into disrepair, I think they wanted the plots for redevelopment. But then, after my parents were rehoused in Bethnal Green, the Spitalfields Trust took them over in 1977.

I was born in 1939 just before the war began and my mother called me Neville after Neville Chamberlain, who she saw as the bringer of peace. I got a lot of stick for that at school. I had two elder brothers, Terry born in 1932 and Douglas born in 1936. My father was a firefighter and consequently we saw a lot of him. I felt quite well off, I never felt deprived. In the house, there was a total of six rooms plus a basement and an outside basement, and we lived in four rooms on the ground floor and on the first floor, and there was a docker and his wife who lived up on the top floor.

My earliest memory is of the basements of Elder St being reinforced as air raid shelters in case the buildings collapsed – and of going down there when the sirens sounded. Even people passing in the street took shelter there. Pedlars and knife-grinders, they would bang on the door and come on down to the basement. That was normal, we were all part and parcel of the same lot. I recall the searchlights, I found it interesting and I wondered what all the excitement was about. War seemed quite mad to me and, when it ended, I remember the street party with bonfires at each end of the street and everybody overjoyed, but I couldn’t understand why they were all so happy. None of the houses in Elder St were damaged.

We used to play out in the street, games like Hopscotch and Tin Can Copper. All the houses had a door where you could go up onto the roof and it was normal for people in the terrace to walk along the roof, visiting each other. You’d be sitting in your living room and there’d be a knock on the window from above, and it was your neighbours coming down the stairs. As children, we used to go wandering in the City of London, and I remember seeing typists typing and thinking that they did not actually make anything and wondering, ‘Who makes the cornflakes?’ Across Commercial St, it was all manufacturing, clothing, leather and some shoemaking – quite a contrast.

After the war, my father worked as a bookie’s runner in the Spitalfields Market, where the porters and traders were keen gamblers, and he operated from the Starting Price Office in Brushfield St. He never got up before ten but he worked late. They were not allowed to function legally and the police would often take them in for a charge – the betting slips had to be hidden if the police came round. At some parts of the year, we were well off but other parts were call the ‘Kipper Season’ which was when the horse-racing stopped and the show-jumping began, then we had very little. I knew this because my pocket money vanished.

I joined the Vallance Youth Club in Chicksand St run by Mickey Davis. He was only four foot tall but he was quite a strong character. He was attacked a few times in the street on account of being short and a few of us used to call up to his flat above the Fruit & Wool Exchange, so that he could walk with us to the club, but then he got ill and died. Tom Darby and Ashel Collis took over running the club, one was a silversmith and the other was a passer in the tailoring trade. We did boxing, table tennis and football, and they took us camping to Abridge in Essex. We got a bus all the way there and it only cost sixpence.

I moved on to the Brady Club in Hanbury St – it changed my outlook on life. They had a music society, a chess society, a drama society and we used to go to stay at Skeate House in Surrey at weekends. If you signed up to pay five shillings a week, you could go on a trip to Switzerland for £15. Yogi Mayer was the club captain. He called me in and said, ‘This is a private chat. We are asking every boy – If you can’t manage the £15, we will make up the shortfall. But this is between you and I, nobody else will know. I believe that everybody in the East End should be able to have an overseas holiday each year.’ It endeared him to me and made a big impression. When I woke in Switzerland, the sight of the lakes and the mountains was such a contrast to Elder St, and when we came back from our fortnight away I got very down – depressed, you would say now. I was the only non-Jewish person in the Brady Club, only I didn’t realise it. On one of the weekends at Skeate House, I did the washing up and dried it with the yellow towel on a Saturday. But Yogi Mayer said, ‘I won’t tell anyone.’

A friend of my brother’s worked in Savile Row and I thought it would be good for me too. I went to French & Stanley just behind Savile Row and they said they did need somebody but not just yet. So then I went to G.Ward & Co and asked if they wanted anybody, and there was this colonel type and he said, ‘Start tomorrow!’ I was fifteen and a bit, I had left school that Christmas-time. It lasted a couple of years and they were good to me. The cutter would give you the roll of work to be made up and say, ‘It’s for a friend of yours, Hugh Gaitskell.’ When I asked the manager what this meant, he said, ‘We’re Labour and they’re not.’

In 1964, I left Elder St for good, when I got married. I met my wife Margaret at work, she was the machinist and I was the cutter. She used to bring in Greek food and I liked it, and she said, ‘Would you like to come and have it where I live? You’ll have no excuse for forgetting the address because it’s Neville Rd!’

When I started in tailoring, the rateable value of the houses in Elder St was low because of the sitting tenants and low rents, and nobody ever moved. We thought it was good, it was a kind of security. The money people had they spent on decorating and, in my memory, it was always warm and brightly decorated. There was a good sense of well-being, that did seem generally to be the case. We were offered to buy both the houses, five and seven Elder St, for eighteen hundred quid but my father refused because we didn’t want them both.”

Neville with his grandmother.

Neville’s mother Ada Sims.

Neville’s father Charles Turner was in the fire service during the war (fourth from left in back row).

Neville as a schoolboy.

Neville’s ration book.

Coker’s Dairy in Fleur de Lis St used to take care of their regular customers – “If you were loyal to them, they’d give you an extra piece of cheese under the counter.”

Neville aged eleven in 1951, photographed by Griffiths of Bethnal Green.

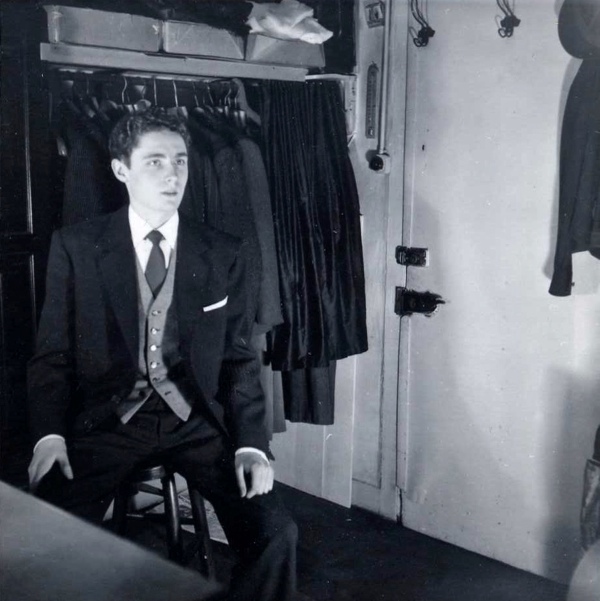

Neville at Saville Row when he began his career as a pattern cutter at sixteen.

Neville’s friend Aubrey Silkoff, photographed when they hitched to Amsterdam in 1961.

Neville’s father Charles owned the only car in Elder St – “We had a car in Elder St when nobody had a car in Elder St, but it vanished when we had no money.”

Neville as a young man.

A family Christmas in Elder St, 1968 – Neville sits next to his father at the dinner table.

Neville’s father, Charles.

Neville and Margaret.

Margaret and Minas.

Neville, Margaret and their son Minas.

Neville’s Uncle Arthur who hung the wisteria wallpaper.

Minas and Terry.

The living room of number seven photographed by the Spitalfields Trust in 1977 with Uncle Arthur’s wisteria wallpaper hanging off the walls.

Dan Cruickshank and others staged a sit-in at number seven to save the house from demolition in 1977.

Neville Turner outside number seven Elder St where he grew up.

You may also like to read about Neville’s childhood friend

In Old Bow

Mid-ninenteenth century Gothic Cottages in Wellington Way

Taking advantage of the spring sunshine, Antiquarian Philip Mernick led me on a stroll around the parishes of Bromley and Bow so that I might photograph just a few of the hidden wonders alongside the more obvious sights.

Edward II granted land to build the chapel in the middle of the road at Bow in 1320 but the nearby Priory of St Leonard’s in Bromley was founded three centuries earlier. These ecclesiastical institutions were the defining landmarks of the villages of Bromley and Bow until both were absorbed into the expanding East End, and the precise locations of these lost territories became a subject of unending debate for residents. More recently, this was the location of the Bryant & May factory where the Match Girls won landmark victories for workers’ rights in manufacturing industry and where many important Suffragette battles were literally fought on the streets, outside Bow Rd Police Station and in Tomlin’s Grove.

Yet none of this history is immediately apparent when you arrive at the handsome tiled Bow Rd Station and walk out to confront the traffic flying by. In the nineteenth century, Bow was laced with an elaborate web of railway lines which thread the streets to this day and wove the ancient villages of Bromley and Bow inextricably into the modern metropolis.

Bow Rd Station opened in 1902

Bow Rd Station with Wellington Buildings towering over

Wellington Buildings 1900, Wellington Way

Wellington Buildings

Suffragette Minnie Lansbury was imprisoned in Holloway and died at the age of thirty-two

Eighteen-twenties terrace in Bow Rd

Bow Rd

Bow Rd

Bow Rd Police Station 1902

Under the railway arches in Arnold Rd

The former Great Eastern Railway Station and Little Driver pub, both 1879

This house in Campbell Rd was built one room thick to fit between the railway and the road

Arnold Rd once extended beyond the railway line

Arnold Rd

Former Poplar Electricity Generating Station

Railway Bridge leading to the ‘Bow Triangle’

In the ‘Bow Triangle,’ an area surrounded on three sides by railway lines

Handsome nineteenth century villas for City workers in Mornington Grove

Former coach house in Mornington Grove

Bollard of Limehouse Poor Commission 1836 in Kitcat Terrace

Last fragment of Bow North London Railway Station in the Enterprise Rental car park

Edward II gave the land for this chapel of ease in 1320

In the former Bromley Town Hall, 1880

Former Bow Co-operative Society in Bow Rd, 1919

The site of St Leonard’s Priory founded in the eleventh century and believed to have been the origin of Chaucer’s Prioress in the ‘Canterbury Tales’ – now ‘St Leonard’s Adventurous Playground’

Kingsley Hall where Mahatma Ghandi stayed when he visited the East End in 1931

Arch by William Kent (c. 1750) removed from Northumberland House on the Embankment in 1900

Draper’s Almshouses built in 1706 to deliver twelve residences for the poor

The refurbished Crossways Estate, scene of recent alleged election skullduggery

You may also like to take a look at

Bug Woman London

I am delighted to publish this extract from BUG WOMAN LONDON – a graduate of my blog writing course who is now celebrating five years of publishing posts online. The author set out to explore our relationship with the natural world in the urban environment, yet her subject matter has expanded to include a brave and tender account of her mother’s decline and death. Follow BUG WOMAN LONDON, because a community is more than just people

I am now taking bookings for the next courses, HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ on May 11th/12th and November 9th/10th. Come to Spitalfields and spend a weekend with me in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Fournier St, enjoy delicious lunches from Leila’s Cafe, eat cakes baked to historic recipes by Townhouse and learn how to write your own blog. Click here for details

If you are graduate of my course and you would like me to feature your blog, please drop me a line.

I do still have one parent alive though, so I ring the nursing home to see how Dad is getting on.

‘I’m on a boat’, he says. ‘I’ll be gone for forty days’.

‘Where are you going, Dad?’ I ask. I have learnt that it is easier for everyone if I join Dad in Dadland rather than attempting to drag him into the ‘real’ world, where he has dementia and his wife of sixty-one years is dead.

‘Northern China’, he says, emphatically.

‘You’ve not been there before, have you? It will be an adventure. I hope the food is good!’

I am not sure if Dad is remembering the business trips that he used to take, or the cruises he went on with Mum, or if this is a metaphor for another journey that he is taking. But I am sure that it could be all three explanations at once.

‘And I’ve done a picture of a rabbit with a bird on its head’.

‘That sounds fun Dad, I know you like painting and drawing’.

‘It’s with crayons’.

‘Well, they’re a bit less messy’.

Dad laughs. There’s a pause.

‘I haven’t been able to talk to Mum. I ring and ring, but she never answers’.

I wonder if he has actually been ringing the house and getting Mum’s voice on the answerphone. He is convinced that she is cross with him because one of the ‘young’ female carers at the home (a very nice lady in her fifties) helped him to have a shower. He went to the funeral and was in the room when Mum died, but does not remember.

‘She’s away at the moment Dad’, I say, ‘But she loves you and she knows that you love her’.

‘That’s all right then,’ he says. ‘But I have to go now’.

‘Love you Dad’.

‘Love you n’all’.

It is as if, in his dementia, Dad is returned to some earlier version of himself – more placid, less anxious. His calls to my brother have gone from forty-three in one day to once or twice a week. I am not sure if this peacefulness will last, or if it presages a movement to another stage in the progression of the disease, but I am grateful for his equanimity. Somewhere inside this frail, vulnerable man there is still my Dad, and I feel such tenderness for him.

I walk to the bedroom and look out of the window. There is something totally unexpected in the garden.

A grey heron is in the pond, and, as I watch, the creature spots the rounded head of a frog. Once the bird is locked on target, there is no escape. The heron darts forward, squashes the frog between the blades of its bill and waits, as if uncertain what to do. The frog wriggles, and the heron dunks it into the water, once, twice. And then the bird throws back its head and, in a series of gulps, swallows the frog alive.

I do not know what to do. I feel protective towards the frogs, but the heron needs to eat too. The frogs have bred and there is spawn in the pond, so from a scientific point of view there is no need to be sentimental. But still. I have been away for two weeks and I suspect that the heron got used to visiting when things when quiet. The pond must have had a hundred frogs in it when we left. Hopefully some of them quit the water once the breeding was over, because on today’s evidence the heron could happily have eaten the lot.

What a magnificent creature, though. It is such a privilege to have a visit from a top predator. Close up, I can see the way that those yellow eyes point slightly forward to look down the stiletto of the beak, and the way that the mouth extends back beyond the bill, enabling an enormous gape. The plume of black feathers at the back of the head show that this is an adult bird, perhaps already getting ready for breeding. The heron leans forward, having spotted yet another frog, and I decide that I will intervene. I unlock the back door and open it, but it is not until I am outside on the patio that the bird reluctantly flaps those enormous wings and takes off, to survey me from the roof opposite.

I know that I will not deter the bird for long – after all, I will leave the house, and the heron will be back. But there has been so much loss in my life in the past few months that I feel as if I have to do something. The delicate bodies of the frogs seem no match for that rapier-bill and there is something unfair about the contest in this little pond that riles me. We are all small, soft-bodied creatures, and death will come for us and for everyone that we love with its cold, implacable gaze, but that does not mean we should not sometimes throw sand in its face. I am so lucky to have the graceful presence of the heron in my garden, but today, I want to tip the balance just a little in favour of the defenceless.

Photographs copyright © Bug Woman London

HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ: 11th-12th May & 9th-10th November 2019

Spend a weekend in an eighteenth century weaver’s house in Spitalfields and learn how to write a blog with The Gentle Author.

This course will examine the essential questions which need to be addressed if you wish to write a blog that people will want to read.

“Like those writers in fourteenth century Florence who discovered the sonnet but did not quite know what to do with it, we are presented with the new literary medium of the blog – which has quickly become omnipresent, with many millions writing online. For my own part, I respect this nascent literary form by seeking to explore its own unique qualities and potential.” – The Gentle Author

COURSE STRUCTURE

1. How to find a voice – When you write, who are you writing to and what is your relationship with the reader?

2. How to find a subject – Why is it necessary to write and what do you have to tell?

3. How to find the form – What is the ideal manifestation of your material and how can a good structure give you momentum?

4. The relationship of pictures and words – Which comes first, the pictures or the words? Creating a dynamic relationship between your text and images.

5. How to write a pen portrait – Drawing on The Gentle Author’s experience, different strategies in transforming a conversation into an effective written evocation of a personality.

6. What a blog can do – A consideration of how telling stories on the internet can affect the temporal world.

SALIENT DETAILS

In 2019 courses will be held at 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields on 11th-12th May & 9th-10th November. Each course runs from 10am-5pm on Saturday and 11am-5pm on Sunday.

Lunch will be catered by Leila’s Cafe of Arnold Circus and tea, coffee & cakes by the Townhouse are included within the course fee of £300.

Accomodation at 5 Fournier St is available upon enquiry to Fiona Atkins fiona@townhousewindow.com

Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book a place on the course.

At Walthamstow Pump House

Tiggy, the Pump House cat

What could be a more appealing excursion over the forthcoming Easter holiday than a trip to a Victorian sewage pumping station in Walthamstow? Although I would not claim to any special interest in mechanical things, I was astonished and delighted by the mind-boggling collection of pumps, engines, trains, buses, fire engines, steam rollers, cranes, historic domestic appliances and model railways to be discovered here.

Unfortunately when the suburban streets of Walthamstow spread across the fields, all the sewage ran downhill and accumulated in the Lee Valley. Undeterred, the Victorians installed massive engines driven by steam power to ensure that their magnificent drainage system kept the effluvium flowing smoothly. So efficient were these sewage pumps, manufactured by William Marshall Sons & Co, that they ran continuously from 1885 for over ninety years until steam power was replaced by electricity in the nineteen-seventies.

At this point, the historic machinery might have been lost forever if a group of local visionaries had not stepped in to cherish the pumps, engines and boilers. One of these far-sighted enthusiasts was Melvin Mantell who took me on a personal tour of some of the highlights of the pump house collection and explained how it all came about.

“For years, I knew Big Dave the heavyweight boxer who ran the greengrocer underneath the railway bridge in Leyton High Rd. One night his wife, an enormous woman, rang me up to ask ‘Are you coming down to the farm to have a look at the engines?’ I thought, ‘What the hell is she on about?’ but I knew she worked for the council at the depot where the rubbish was dumped. She said, ‘The old pump house has got steam engines in it.’ All the years I had been going there with my dad, dumping rubbish and seeing the building but ignoring it. She said, ‘We’re having an open day, would you like to visit?’

Me and a few others, we decided to come down on Thursday evenings and take care of the engines. We were known as the ‘Friends of the Pump House.’ At first, we were just cleaning off the rust with a Brillo pad and some oil, but my dad and old Reggie Watlings, the surface grinder who has been dead a long while, they restored the engines. We stripped them down and rebuilt them completely. Now we come down here every Tuesday, Thursday and Sunday during the day. We love everything about this place. We are open every Sunday for visitors free of charge and we get a lot of visitors coming in. It is quite staggering.”

What makes this museum so charismatic is that it has been accumulated by enthusiasts rather than organised for any didactic purpose and it was my pleasure to spend a morning with the small band of volunteers who tend to it each week. Cramming all these objects into a cabinet of wonders emphasises a joyous delight in human ingenuity as expressed through mechanical contrivances of all kinds. If you are seeking a celebration of the East End’s heritage of industry and technological innovation, this is the place.

Melvin Mantell – “I was born in Brewster Rd in Leyton in 1947 and I still live in that house today. I started work in 1969 in a builders’ merchants and then I went into the trade doing carpentry work, which I had learnt at school, staying on to get qualifications. Carpentry is my thing, including woodturning, and I have made furniture and cabinets.”

Sid Bell works in restoration of artefacts. ‘I was born in Forest Gate and my first job was at Nonpareil Engineering in Walthamstow. When I was fifteen then I went into making hydraulic motors of cast iron used in the construction of the Victoria Line. They could not have sparks down there because of the risk of explosion so engines were driven by oil pressure. I have built railway engines and made all the parts myself. Nowadays, I am retired and I help old people out in their gardens, and I am here three days a week. I made all these displays and organised the tools.’

In the Pump House

Entrance to the Pump House

Tube trains under repair

Abdul Seba is the IT manager and works on the restoration of trains

Melvin with a favourite bus from his collection

Steam roller

Historic domestic appliances

Walthamstow in miniature

A model of Walthamstow Station

A model of Liverpool St Station

Mozz Blunden, company secretary, location manager, painter, canteen manager and toilet cleaner