Philippa Stockley’s Restoration Stories

After reporting on London homes and their owners in the Evening Standard for twenty years, Philippa Stockley has written RESTORATION STORIES, a book about old, mainly Georgian, houses and the heroic souls who saved them

A back yard in Spitalfields

Raised in suburban Surrey, I dreamed of London. Mine was a romantic, book-provoked dream with a twinge of David Copperfield, but many of us rebel against what we knew as children. Though whether I would rebel if I had been raised in a castle or an old rectory was never tested, for ours was an ordinary family house with a big garden.

It was a perfect environment to nurture fantasies of grandeur, enriched by novels. Fantasies that usually included a Georgian house with a gravel sweep and tall windows, or something resembling a house in a film or television adaptation. Always old, often grand, but sometimes a decrepit house with sun-shafted dust and elegant mystery. It made no difference that much of the allure was created by set dressers. For me, beauty – however achieved – has always been the thing.

My actual experience of London was limited to thrilling rare excursions — for fireworks or to feed the ducks in St James’s Park on a snatched lunch hour with my father. Rareness and desirability so often go together.

Eventually I inveigled myself into London, staying in small or transitory places until I won a scholarship to study clothing history at the Courtauld Institute. During my second year, I shared a modest Georgian house in Eel Brook Common with other students. Of aged London stock with a somnolent flagged back yard, it was the first Georgian house I lived in. While some rooms were small and at dusk it could be gloomy, it was lovely and felt completely right.

While studying, I designed and made the costumes for a production of Edward Bond’s Restoration, hammering them out on a miniature sewing machine. My budget was tiny, but I had heard of street markets in the East End. Rumour had it that there were great shed-like warehouses selling heaps of tat in glorious abundance and old clothing emporia, and murky carparks converted into seas of wonder, to navigate sustained by bagels and hot coffee.

For a few ice-sodden Sundays I set out at dawn and bought dodgy mink and rabbit tippets, and boxes of military buttons later safety-pinned to waistcoats and breeches. But I also encountered a clutch of streets whose derelict beauty was like a double-handed slap. It was a very cold winter. My memory of that time sparks with ice. Those cobbled streets, Fournier, Wilkes, Princelet — names themselves romantic — appeared steel-grey, frozen, sprinkled with hoarfrost and fairy-dust in equal measure. Windows were broken or boarded, timber and lead porticos were decaying, yet they were the most magical houses and the most beautiful streets I had ever seen. Walking among them was like walking through the pages of a forgotten book or stepping into a faded postcard. In memory they smouldered, the colour of ashes, yet lay restless in my mind and broke into my heart. Even if I could not afford one, I never forgot them.

Later, others bought and restored them, several of which now smile gravely from the pages of my book. They feel like old friends. All different and with strong personalities. Now that they have simmered in my heart for years, I have tried to give a glimpse of them and of the people who saved them.

The accounts that their owners gave of restoring their homes were fascinating and often funny. Many were wry or poignant, all were passionate. All talked as if their houses were alive – which they are – and as if they had distinct characters – which they do. I believe people who adopt these houses are the same sort who go to animal shelters in search of a small manageable dog and come away with two former greyhounds – one lame – a blasphemous parrot and an old, lunatic cat. The determination to save, to nurture and restore, mixed with a dollop of eccentricity, is always there. A warmth, a largeness of spirit, much generosity, a hint of genial lunacy. These are the characteristics of those who save old houses.

When I write about homes in the Evening Standard, I always write about the house and its owner as inseparable, which makes every story unique. But Georgian houses are special: not only because of their age but because of their grace.

When describing that grace, proportions are often mentioned: the ratio of glazing to brickwork, the pattern of mouldings, the measure of dado-panelling to wall height and the form of the panels. All a given. Yet it is the millions of small constituents, making up the complex that fascinate me more – all the handmade things that together, bit by bit, become a house. Grace slumbers ineffable in every one, from the humblest, the bricks and the lime mortar joining them, to the slow-grown, hand-sawn timber joists, the hand-cut slate tiles or hand-moulded clay pantiles. Then, glass blown white hot and miraculously flattened, bubbling, for window panes, plaster smoothly laid over hand-cut laths, and — oh! — hand- or bucket-mixed paint. Paint mixed to recipes passed from one painter to the other. Very simple for plain colours: the quotidian slubs and duns and off-whites, the quick cheap fake mahogany and pleasant ochres. But also, colours mixed by eye, practice and judgement, by the skill that comes with repetition. Paints mixed with knowledge, not by a machine – made with oil for longevity and satisfying sheen, to protect but also to add gentle tones made with natural earth pigments.

Some of the houses I have written about are nearly three hundred years old – and one is much older – yet their inhabitants find that life with electricity, gas and wi-fi sits well alongside Georgian beauty. What unites these people is that they put beauty first. Their houses share similar temperaments, yet each is completely different. And in every case its beauty speaks for itself.

I enjoy the fact that many were built on just a few courses of bricks. Their neighbours, their half-basements, and their solid but flexible flagged floors of thick stone laid directly on to sand or dirt hold them up effectively – supplemented occasionally with lengths of steel today. They prove that there are economical and renewable ways to construct homes compatible with modern life. If we built them now, they could stand into the twenty-fourth century.

The smallest were usually dubbed ‘fourth-rate.’ These were often narrow terrace houses of three or four floors including attic and half-basement. Today, it is a perfect size for a couple or young family. Yet some are just fourteen-foot wide — my own is a case in point. It reminds me of an upended caravan. It is not large yet it is ample and this graceful sufficiency is another Georgian trick, unlike later Victorian two-up-two-downs, which introduced meanness and a rather glum squatness. Houses like mine demonstrate an economical use of the plot with a light footprint both actually and metaphorically, while retaining the proportions of their grand cousins. These fourth-rate houses are the soot-blackened town mice, the London sparrows.

They also remind anyone who makes things that will not last or cannot be recycled, or who continues to argue in favour of demolition and shoddy, short-term building, that houses made of brick, lime, timber, and stone live, breathe and move, and if left alone will do so for a very long time. They shift and whisper, creak and murmur, particularly on London clay. Architects and planners should study them afresh.

In Elder St

In Mile End

In Elder St

In Fournier St

In Whitechapel

In Elder St

In Whitechapel

In Elder St

In Cable St

In Fournier St

In Fournier St

In Elephant & Castle

On the Isle of Sheppey

In Elephant & Castle

In Whitechapel

In Cable St

Photographs copyright © Charlie Hopkinson

RESTORATION STORIES by Philippa Stockley is published by Pimpernel Press today

You may also like to read about

Eleanor Crow’s Butchers

An exhibition of Eleanor Crow’s watercolours of classic London shopfronts featuring many paintings from her book SHOPFRONTS OF LONDON, In Praise Of Small Neighbourhood Shops is at Townhouse in Fournier St from Friday 4th October. You are all invited to the opening and book launch this Thursday 3rd October from 6:00pm.

Eleanor will giving an illustrated lecture at Wanstead Tap on Wednesday 9th October, showing her pictures and telling the stories of the shops. Click here for tickets

Click here to order a signed copy of Eleanor’s book for £14.99

W. A. Down & Son, The Slade, Plumstead

“Butchers have enjoyed an unlikely renaissance recently due to an increased interest in provenance and a suspicion of processed meat in the light of the horse meat scandal. Consequently, customers are now willing to spend more to buy better quality meat despite the presence of a nearby supermarket. A butcher can sell a range of cuts for all budgets, as well as offering advice on how to prepare and cook the meat. The rise of the celebrity chef has also contributed, encouraging people to seek out specialist and traditional butchers, and to buy meat in the old-fashioned way.” – Eleanor Crow

M & R Meats, St John St, Clerkenwell

Hussey’s, Wapping Lane

J Whenlock, Barking Rd, Plaistow

The Cookery, Stoke Newington High St

W. D. Chapman, High Rd, Woodford Green

The East London Sausage Company, Orford Rd, Walthamstow

The Butchers Shop, Bethnal Green Rd

J. Geller, High Rd, Leytonstone

Meat N16, Church St, Stoke Newington

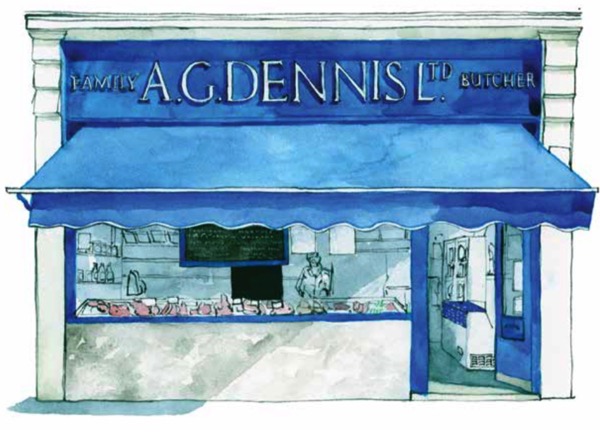

A. G. Dennis, High St, Wanstead

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £14.99

At a time of momentous change in the high street, Eleanor’s witty and fascinating personal survey champions the enduring culture of Britain’s small neighbourhood shops.

As our high streets decline into generic monotony, we cherish the independent shops and family businesses that enrich our city with their characterful frontages and distinctive typography.

Eleanor’s collection includes more than hundred of her watercolours of the capital’s bakers, cafés, butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers, chemists, launderettes, hardware stores, eel & pie shops, bookshops and stationers. Her pictures are accompanied by the stories of the shops, their history and their shopkeepers – stretching from Chelsea in the west to Bethnal Green and Walthamstow in the east.

A Walk With Shloimy Alman

Let us join photographer Shloimy Alman as he wanders the streets of the East End in the seventies accompanied by the Yiddish poet Avram Stencl. Alman’s photographs are published for the first time here today and can be seen in a one day exhibition at Sandys Row Synagogue next Sunday 6th October, 11:00am-6:00pm. Click here to book a ticket

Photographs copyright © Shloimy Alman

You may also like to take a look at

Shloimy Alman, Photographer

Rachel Lichtenstein introduces the photographs of Shloimy Alman, which are published here for the first time and will be the subject of a one day exhibition at Sandys Row Synagogue next Sunday 6th October, 11:00am-6:00pm. Click here to book a ticket

Harvey Rifkind, president of the synagogue, told Rachel about this collection of unseen photography taken in the seventies and, in May this year, Harvey and Rachel visited Shloimy in Israel where Rachel interviewed him and scanned over three hundred of his pictures.

Rachel’s piece features excerpts from her interview with Shloimy.

Shloimy Alman was born in Manchester in 1950, three years after his Polish Jewish parents arrived in England in 1947. His father Moishe came from Tarłów, a small town half way between Krakow and Warsaw. He taught Yiddish before the war and became active in the Bund in Wlotzlawek. His first wife and child were killed during the Holocaust. Moishe spent the war years in a Siberian labour camp working as a lumberjack.

After the war Moishe was instrumental in starting the first Yiddish school for the surviving Jewish children in Walbrzych, which is where he met his second wife Sara Scheingross, Shloimy’s mother, and her daughter Eva, aged six. In 1947, Sara and Moishe married and left for Manchester where Moishe’s two brothers had settled before the First World War. ‘For my mother after coming from pre-war Warsaw which was, in terms of style akin to Paris, Manchester was a disappointment to her,’ Shloimy recalled.

His parents craved the vibrant Yiddish culture of Poland which was largely missing in post-war Manchester, although there were still a number of Jewish shops and businesses, particularly in the Cheetham Hill Rd, High Town and Strangeways areas. Shloimy would accompany his mother on shopping trips. ‘There were very few children of my pre-school age then who were speaking Yiddish so I was an attraction,’ he said. ‘When we went to the grocer, he’d shove his hand in the barrel and shlept out a sour cucumber for me. If we went to the deli, I’d have a stick of vursht. When we went to buy the live chicken, before taking it to the slaughterhouse, the owner would find a warm egg, then poke some holes in so I could suck the egg. I was a child celeb, in many ways spoilt rotten by most of the shopkeepers because I spoke to them in Yiddish.’

Shloimy’s Uncle Lazar had a barber’s shop and was involved in Yiddish literary and Zionist circles. ‘He had an amazing Yiddish library upstairs and, despite the fact he was a working man and had no formal education, he was tremendously well read. When the Yiddish theatre came to Manchester the actors would be put up on the barber’s chairs to sleep overnight and served the most magnificent breakfast by Lazar in the morning.’

Lazar introduced Shloimy’s parents to the monthly Yiddish magazine Loshn un Lebn (Language & Life), edited and compiled by London’s foremost Yiddish poet, another Polish émigré, Avram Stencl. They took a monthly subscription ‘and looked forward to its arrival with tremendous pleasure, reading the magazine from cover to cover.’ Moishe was soon writing articles in Yiddish for the magazine. ‘My father never went to London and Stencl never came to Manchester but they regularly wrote to each other.’

After Moishe died in 1964, ‘even when my mother had no money, she still kept up her subscription and read the magazine religiously’ said Shloimy. One Saturday afternoon she went to London and sang at the Saturday afternoon Friends of Yiddish meetings, which Stencl had established in 1936 after his arrival from Poland. Shloimy grew up hearing stories about the legendary Yiddish poet and years later after his parents had died, he wrote to the poet and asked if they could meet.

Like the Manchester Jewish shopkeepers of his childhood, Stencl was delighted to hear from someone of Shloimy’s generation who was a fluent Yiddish speaker and he invited the youth worker in his twenties from Manchester to meet him in Whitechapel. They met for the first time in the summer of 1977 in the ABC café near Whitechapel Station. ‘It was the place where quite a few of the people would meet before the Saturday afternoon meetings to have tea and cake, then they would all walk off together to Stepney Green to Beaumont Hall, where the meetings took place.’

The poet was already in his mid-seventies by then. ‘He cut an impressive figure,’ said Shloimy, ‘with his electric blue eyes, trilby hat and well-cut but shabby suit. He always had a copy of Loshn un Lebn under his arm and was always trying to hawk it.’

On their first walk, Stencl led him to Bevis Marks Synagogue in the city, the oldest synagogue in London, established by Sephardi Jews in the seventeenth century. ‘He walked very quickly for an old man I had trouble keeping up with him. As we walked and talked, in Yiddish of course, he pointed out places on the way, where the Jews Free School had been, the site of the Jewish Soup Kitchen, Bloom’s restaurant on Whitechapel High St and the many small synagogues, which were still operating.’ Shloimy was amazed by the amount of Jewish institutions, shops and people still evident. ‘People kept telling me the Jewish East End was dead but for me, coming from Manchester, it was buzzing with life and activity.’

They passed run-down tenement blocks and stopped briefly at Whitechapel Library, known as ‘the university of the ghetto.’ After their walk, Shloimy went with Stencl to the Friends of Yiddish meeting. There were about twenty people there who were all very welcoming. After this first, visit Shloimy began attending these meetings regularly whilst visiting his parents-in-law in London. ‘I wanted to be in that atmosphere that my parents so loved, to hear Yiddish literature being spoken and talked about again. It was most important. Stencl invariably opened with one of his poems, then he would discuss anything from the Torah portion of the week to a current piece of news. Others sang, really put their soul into it, lots of different people got up to speak, read, anything went, as long as it was in Yiddish.’

After his initial walk around Whitechapel with Stencl, Shloimy started exploring by himself before the Shabbat meetings, often drifting around the streets, coming across things by accident. ‘Knowing that places like Commercial Rd were important, I’d wander along and see a Jewish shop name and photograph it.’ He spent days recording Jewish life, from shuls to deli’s, shops, market stalls and traders. He recorded the textile-trimming merchants. ‘I love this picture of three gentlemen with trilby hats selling cloth. My father was a tailor’s son, that’s how he always described himself. My father sewed beautifully, my grandfather’s eldest son became a tailor and his eldest son became a tailor, and I remember going to buy cloth with my father and watch the way he felt it, stretched it, it was an art, a science.’

He recorded kosher poulterers in Hessel St. ‘Shop after shop, stalls with chickens plucked and hanging from a barrow, they were all surviving, all doing business, it was still a rich Jewish landscape.’ He took photographs of kosher wine merchants, the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre – ‘I remember some of the actors who played there coming to Manchester and staying at my uncle’s house’ and the site of the Federation of Synagogue offices in Greatorex St, where he visited the Kosher Luncheon Club run by Connie Shack in the same building where ‘You got a good meal for a reasonable price – it had a specific European style.’

He took slides of the Jewish bakeries – Free Co, Cohen’s, Kossoff’s, Grodzinski’s and beigel shops in East London at the time. ‘They were all friendly, loved me coming in and chatting in Yiddish and taking a picture.’ He went into the Soup Kitchen on Brune St, which was sending out pre-packed food ‘Jacobs Crackers, eggs, Dairylea cheese, spaghetti’ to elderly Jews living in the area.

On Brick Lane, he photographed Jewish booksellers, newsagents, textile merchants. ‘All these places existed, everything the community needed – it told me how large the community still was. It wasn’t on its last legs, it was vibrant.’ On Cheshire St he saw the work of Jewish cabinet makers outside their workshops and during one visit he managed to get inside the Cheshire St Synagogue, ‘which was the most remarkable find, it was a Shabbat and the door was slightly open so I went inside and saw all this beautifully lathed woodwork done by the cabinet makers of the street. It was a working man’s shul, around the walls the donations were listed, some as little as two guineas. They made this place with their own hands. And because of the wood the synagogue had this warm, welcoming atmosphere. When I went there, there were exactly ten men praying, they had the most magnificent Kiddush, almost a full meal at the end of the service, arranged for them by the Bangladeshi caretaker because nobody lived near the shul, and they all had a long walk back home.’

He photographed the entrance to Black Lion Yard, once known as ‘the Hatton Garden of the East End’ because of all the jewellery shops there, although most of the street and shops had been demolished by then. He took pictures of the Whitechapel Waste, of the market stalls and street life, of Stencl selling his magazine to an alter bubby (old grandmother), the London Hospital, the nearby Brady St dwellings, ‘dark and ominous looking tenements which were pulled down soon after.’ He explored the back streets, visited little shops, tobacconists, market stalls and Jewish delis. ‘Roggs was my favourite, he’d always be in that old vest, sticking his great hairy arms into a barrel of cucumbers he pickled himself.’ He photographed the window of the room in Tyne St where ‘Sholem Aleichem stayed on his way to America from Odessa.’ Most of the time Shloimy walked alone but sometimes Stencl would join him. On one of these walks Stencl took him to Narod Press on Cavell St where Loshn un Lebn was printed and introduced him to the typesetter, a shy orthodox man who allowed Shloimy to take his portrait.

Overtime Shloimy became real friends with Stencl who he described as ‘a Hasid of Whitechapel. The place was good to him, it gave him a home, it gave somewhere he could write in peace (apart from the Blitz of course), he was always grateful for that, his poetry expresses his love for the place.’

Shloimy also fell in love with the area and he documented what he saw. He said, ‘I am not a photographer, I make no claim. The reason that I started this is I wanted to be able to show my children about Jewish life in England before I immigrated to Israel. It was obvious to me that what I was looking at was soon to vanish. It might be because I was an outsider that I saw this so acutely or because I had already witnessed this disappearance of Jewish life in Manchester. For an intense period of time I photographed what I considered important landmarks and eating places of Jewish London.’

His photographs capture the era absolutely and survive as a unique record of a disappeared world.In 1978 Shloimy, his wife Linda and twins made Aliya to Israel, and since December 1982 he has lived in the collective village of Kfar Daniel.

Photographs copyright © Shloimy Alman

You may also like to take a look at

All Change At Barney’s Eels

Photographer Stuart Freedman was down in Chambers St next to the Tower of London before dawn last week to record the last ever boiling of eels at Barney’s Seafood. In common with many East End businesses operating under railway arches, Barney’s were confronted with an exorbitant rent increase of 400% by Network Rail. Then, once the arches were sold, they were given notice to quit by the end of the month so a neighbouring hotel can expand onto their site.

Fortunately, proprietor Mark Button has taken this as an opportunity to enlarge his business and move to Billingsgate Market on the Isle of Dogs where his regular customers will still be able to pick up their supplies of freshly-boiled eels, thereby guaranteeing the continuing supply of this most traditional of East End delicacies.

I was lucky enough to sit in the office and enjoy a chat over a quiet cup of tea with Mark’s son Harry Button while the phone rang off the hook with eager customers wanting their eels. Mark is the third generation in the family business and passionate to carry it forward into the future.

“I started here three years ago. My dad and uncle work here, and it was my grandad’s before them. There were two brothers Tubby and Barney Solomon, one had Tubby Isaac’s Jellied Eels stall and the other had Barney’s Jellied Eels stall on opposite sides of the road in Goulston St. People swore blind that one stall was better than the other but Barney’s supplied them both. All their eels came from here, Chambers St. This was originally a lock-up for the two stalls but when my grandad Eddy Button bought the business in the sixties he turned it into a factory and a shop.

I’ve been down here since I was knee-high, there’s pictures of me holding crabs as a baby. I spent my summers here. Working with your family isn’t the easiest of things. We have our arguments but we get over it in ten minutes. Today was our last boiling of eels here. It’s a sad day because we have been here so long. Eels have been boiled here in since the nineteen-thirties. We are moving to Billingsgate Market, where we are going to have a shop and we’d love to see our customers there.”

Once we had finished our tea, Ernie Peachum known as ‘Ginger,’ emerged from the kitchen where he had been chopping and boiling eels since five that morning and told me his story.

“I have been here thirteen years. I worked for Mick’s Eels for eight years and then I came here, so over twenty years boiling eels. It’s quite enjoyable. When I left school, my sister was going out with a guy called Dennis who worked for Mick’s Eels. I had a choice to be an electrician or a plumber or go in the eel game – and the eel game has given me three times the amount of money.

The skill lies in not cutting your fingers off. I don’t wear a metal glove because I don’t need to. I use a big knife and I have never seriously cut myself but my stepson who works here nearly took a finger off. Luckily he had not been here that long and did not know how to sharpen the knife, so it stopped when it hit the bone. He was out for a little bit and now he wears a metal glove. You learn to respect the knife but it hurts if you cut yourself.

When I first started, I was scared of an eel but I got over it with experience. I like working on my own, only talking when I have to. It gives me time to think. I start at five in the morning and finish at half one. It’s sad in a way that we are moving but in my eyes things happen for a reason. We are moving to nicer premises and we are expanding.”

Simon Brennan and Ernest ‘Ginger’ Peachum gutting and chopping eels

Harry Button seeks Simon’s lighter

Ernest and Simon

Simon Brennan

Simon boiling eels

Mark & Harry Button of Barneys Seafood

Photographs copyright © Stuart Freedman

You may also like to take a look at

The Pearly Kings & Queens’ Harvest Festival

Tomorrow is the annual Pearly Kings & Queens’ Harvest Festival, gathering in Guildhall Yard at 12:30pm followed by a service at St Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside

On the last Sunday afternoon in September, the Pearly Kings & Queens come together from every borough of London and gather in the square outside the Guildhall in the City of London for a lively celebration to mark the changing of the seasons.

On my visit, there was Maypole dancing and Morris Dancing, there was a pipe band and a marching band, there were mayors and dignitaries in red robes and gold chains, there were people from Rochester in Dickensian costume, there were donkeys with carts and veteran cars, and there was even an old hobby horse leaping around – yet all these idiosyncratic elements successfully blended to create an event with its own strange poetry. In fact, the participants outnumbered the audience and a curiously small town atmosphere prevailed, allowing the proud Pearlies to mingle with their fans, and enjoy an afternoon of high-spirited chit-chat and getting their pictures snapped.

I delighted in the multiplicity of designs that the Pearlies had contrived for their outfits, each creating their own identity expressed through ingenious patterns of pearl buttons, and on this bright afternoon of early autumn they made a fine spectacle, sparkling in the last rays of September sunshine. My host was the admirable Doreen Golding, Pearly Queen of the Old Kent Rd & Bow Bells, who spent the whole year organising the event. And I was especially impressed with her persuasive abilities in cajoled all the mayors into a spot of maypole dancing, because it was a heartening sight to see a team of these dignified senior gentlemen in their regalia prancing around like eleven year olds and enjoying it quite unselfconsciously too.

In the melee, I had the pleasure to grapple with George Major, the Pearly King of Peckham (crowned in 1958), and his grandson Daniel, the Pearly Prince, sporting an exceptionally pearly hat that is a century old. George is an irrepressibly flamboyant character who taught me the Cockney salute, and then took the opportunity of his celebrity to steal cheeky kisses from ladies in the crowd, causing more than a few shrieks and blushes. As the oldest surviving member of one of the only three surviving original pearly families, he enjoys the swaggering distinction of being the senior Pearly in London, taking it as licence to behave like a mischievous schoolboy. Nearby I met Matthew (Daniels’s father) – a Pearly by marriage not birth, he revealed apologetically – who confessed he sewed the six thousand buttons on George’s jacket while watching Match of the Day.

Fortunately, the Lambeth Walk had been enacted all round the Guildhall Yard and all the photo opportunities were exhausted before the gentle rain set in. And by then it was time to form a parade to process down the road to St Mary-le-Bow for the annual Harvest Festival. A distinguished man in a red tail coat with an umbrella led the procession through the drizzle, followed by a pipe band setting an auspicious tone for the impressive spectacle of the Pearlies en masse, some in veteran cars and others leading donkeys pulling carts with their offerings for the Harvest Festival. St Mary-le-Bow is a church of special significance for Pearlies because it is the home of the famous Bow Bells that called Dick Whittington back to London from Highgate Hill, and you need to be born within earshot of these to call yourself a true Cockney.

The black and white chequerboard marble floor of the church was the perfect complement to the pearly suits, now that they were massed together in delirious effect. Everyone was happy to huddle in the warmth and dry out, and there were so many people crammed together in the church in such an array of colourful and bizarre costumes of diverse styles, that as one of the few people not in some form of fancy dress, I felt I was the odd one out. But we were as one, singing “All Things Bring and Beautiful” together. Prayers were said, speeches were given and the priest reminded us of the Pearlies’ origins among the costermongers in the poverty of nineteenth century London. We stood in reverent silence for the sake of history and then a Pearly cap was passed around in aid of the Whitechapel Mission.

Coming out of the church, there was a chill in the air. The day that began with Summery sunshine was closing with Autumnal rain. Pearlies scattered down Cheapside and through the empty City streets for another year, back to their respective corners of London. Satisfied that they had celebrated summer’s harvest, the Pearlies were going home to light fires, cook hot dinners and turn their minds towards the wintry delights of the coming season, including sewing yet more pearl buttons on their suits during Match of the Day.

You may also like to read about

Origins Of Facadism

In today’s extract from my forthcoming book THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM I explore the origins of facadism, the bizarre architectural fad that is currently blighting the capital.

I now at halfway and need to raise another £2,400 to publish my book next month, so I ask you to empty your piggy banks and tip out your sixpences. Click here to help

You can also support publication by ordering a copy in advance for £15. Click here to preorder

I was always familiar with suburban houses adding porticos to enhance their status, cathedrals adorned by elaborate gothic west fronts and country houses evolving with the fortunes of successive generations through the addition of larger and grander classical façades. Some of the greatest of our cathedrals and country houses are the outcome of this approach to architecture, palimpsests in which the building’s evolution can be read by the perceptive viewer. In the past, new frontages were added to old buildings to modernise them or increase their importance. Yet in my time I have witnessed the in- verse – the removal of the former building and the retention of the façade.

The origin of façadism lies in the myth of the Potemkin Villages along the banks of the Dnieper River, built to impress Empress Catherine the Great on her visit to the Crimea in 1787 by her former lover Field Marshal Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin. Allegedly, painted façades with fires glowing behind were constructed by Potemkin when he was Governor of the region to give the Empress, sitting in her barge, the impression of Russian settlement in contested territory only recently annexed from the Ottoman Empire.

How appropriate that this story is without any convincing provenance and may contain no more reality that the façades it describes. Although this tale was likely invented by Potemkin’s political rivals, the legend of the Potemkin Villages has passed into common lore as a means to discuss notions of falsehood, whether architectural or ideological. Yet in the twentieth century, this fiction became a reality as successive authoritarian powers constructed façades to serve their nefarious purposes.

The Theresienstadt concentration camp was used by the Nazis from 1941 as a way-station to the Auschwitz death camp. When the Danish Red Cross insisted on an inspection in 1944, façades of shops, a cafe and a school were constructed as part of a beautification programme which succeeded in convincing the inspectors that nothing was amiss.

During the fifties, North Korea built Kijongdong as a model village designed to be seen from across the border in South Korea. The propaganda message was that this was an affluent settlement with a collective farm, good quality housing, schools and a hospital, but the reality was that these buildings were empty concrete shells in which automated lights went on and off.

In a strange enactment of the Potemkin Villages, when Vladimir Putin visited Suzdal in 2013, derelict buildings were covered with digitally-printed hoardings showing newly-built offices of glass and steel. Similar printed hoardings are often to be seen in London with images of the buildings behind, sheltering them from public view while the practice of façadism is underway.

You might conclude that these grim authoritarian precedents would discredit façadism as an acceptable practice entirely, yet it was legitimised by postmodernism at the end of last century. Irony and discontinuity were defining qualities of postmodern architecture, permitting architects to play games with façades and fragments of façades without any imperative to deliver an architectural unity. The ubiquitous façadism of today is the direct legacy of this movement, except now it is enacted without inverted commas and licensed as orthodox in the vocabulary of contemporary architecture.

Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin (1739-91), after Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder

Drawing by Bedřich Fritta, a prisoner at Terezín, depicting the ‘beautification’ of the ghetto-camp undertaken by the SS before the Red Cross visit in 1944

Kijongdong, a Potemkin village built in North Korea as a model settlement designed to be seen from across the border in South Korea

Digitally-printed facade fitted to hide dereliction for Vladimir Putin’s visit to Suzdal, Russia, in 2013

An example of postmodern facadism

Imminent facadism at the former Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel

Imminent facadism in Norton Folgate where British Land are retaining only the front piers of the Victorian warehouses

Facadism proposed by Sir Norman Foster for the corner of Commercial St

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY FOR £15

“As if I were being poked repeatedly in the eye with a blunt stick, I cannot avoid becoming increasingly aware of a painfully cynical trend in London architecture which threatens to turn the city into the backlot of an abandoned movie studio.”

The Gentle Author presents a humorous analysis of facadism – the unfortunate practice of destroying an old building apart from the front wall and constructing a new building behind it – revealing why it is happening and what it means.

As this bizarre architectural fad has spread across the capital, The Gentle Author has photographed the most notorious examples, collecting an astonishing gallery of images guaranteed to inspire both laughter and horror in equal measure.

You may also like to take a look at