The Harvest Festival Of The Sea

Today we preview the annual Fish Harvest Festival which will be held at St Mary-at-Hill next Sunday October 13th

Frank David, Billingsgate Porter for sixty years

Thomas à Becket was the first rector of St Mary-at-Hill in the City of London, the ancient church upon a rise above the old Billingsgate Market, where each year at this season the Harvest Festival of the Sea is celebrated – to give thanks for the fish of the deep that we all delight to eat, and which sustained a culture of porters and fishmongers here for centuries.

The market itself may have moved out to the Isle of Dogs in 1982, but that does not stop the senior porters and fishmongers making an annual pilgrimage back up the cobbled hill where, as young men, they once wheeled barrows of fish in the dawn. For one day a year, this glorious church designed by Sir Christopher Wren is recast as a fishmongers, with an artful display of gleaming fish and other exotic ocean creatures spilling out of the porch, causing the worn marble tombstones to glisten like slabs in a fish shop, and imparting an unmistakeably fishy aroma to the entire building. Yet it all serves to make the men from Billingsgate feel at home, in their chosen watery element – as I discovered when I went along to join the congregation.

Frank David and Billy Hallet, two senior porters in white overalls, both took off their hats – or “bobbins” as they are called – to greet me. These unique pieces of headgear once enabled the porters to balance stacks of fish boxes upon their heads, while the brim protected them from any spillage. Frank – a veteran of eighty-nine years old – who was a porter for sixty years from the age of eighteen, showed me the bobbin he had worn throughout his career, originally worn by his grandfather Jim David in Billingsgate in the eighteen-nineties and then passed down by his father Tim David.

Of sturdy wooden construction, covered with canvas and bitumen, stitched and studded, these curious glossy black artefacts seemed almost to have a life of their own. “When you had twelve boxes of kippers on your head, you knew you’d got it on,” quipped Billy, displaying his “brand new” hat, made only in the nineteen thirties. A mere stripling of seventy-three, still fit and healthy, Billy started his career at Christmas 1959 in the old Billingsgate market carrying boxes on his bobbin and wheeling barrows of fish up the incline past St Mary-at-Hill to the trucks waiting in Eastcheap. Caustic that the City of London revoked the porters’ licences after more than one hundred and thirty years – “Our traditions are disappearing,” he confided to me in the churchyard, rolling his eyes and striking a suitably elegiac Autumnal note.

Proudly attending the spectacular display of fish in the porch, I met Eddie Hill, a fishmonger who started his career in 1948. He recalled the good times after the war when fish was cheap and you could walk across Lowestoft harbour stepping from one herring boat to the next. “My father said, ‘We’re fishing the ocean dry and one day it’ll be a luxury item,'” he told me, lowering his voice, “And he was right, now it has come to pass.” Charlie Caisey, a fishmonger who once ran the fish shop opposite Harrods, employing thirty-five staff, showed me his daybook from 1967 when he was trading in the old Billingsgate market. “No-one would believe it now!” he exclaimed, wondering at the low prices evidenced by his own handwriting, “We had four people then who made living out of just selling parsley and two who made a living out of just washing fishboxes.”

By now, the swelling tones of the organ installed by William Hill in 1848 were summoning us all to sit beneath Wren’s cupola and the Billingsgate men, in their overalls, modestly occupied the back row as the dignitaries of the City, in their dark suits and fur trimmed robes, processed to take their seats at the front. We all sang and prayed together as the church became a great lantern illuminated by shifting patterns of October sunshine, while the bones of the long-dead slumbered peacefully beneath our feet. The verses referring to “those who go down the sea in ships and occupy themselves upon the great waters,” and the lyrics of “For those in peril on the sea” reminded us of the plain reality upon which the trade is based, as we sat in the elegantly proportioned classical space and the smell of fish drifted among us upon the currents of air.

In spite of sombre regrets at the loss of stocks in the ocean and unease over the changes in the industry, all were unified in wonder at miracle of the harvest of our oceans and by their love of fish – manifest in the delight we shared to see such an extravagant variety displayed upon the slab in the church. And I enjoyed my own personal Harvest Festival of the Sea in Spitalfields for the next week, thanks to the large bag of fresh fish that Eddie Hill slipped into my hand as I left the church.

St Mary-at-Hill was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren in 1677

Senior fishmongers from Billingsgate worked from dawn to prepare the display of fish in the church

Fishmonger Charlie Caisey’s market book from 1967

Charlie Caisey explains the varieties of fish to the curious

Frank David and Billy Hallet, Billingsgate Porters

Frank’s “bobbin” is a hundred and twenty years old and Billy’s is “brand new” from the nineteen thirties

Billy Hallet’s porter’s badge, now revoked by the City of London

Jim Shrubb, Beadle of Billingsgate with friends

The mace of Billingsgate, made in 1669

John White (President & Alderman), Michael Welbank (Master) and John Bowman (Secretary) of the Billingsgate Ward Club

Dennis Ranstead, Sidesman Emeritus and Graham Mundy, Church Warden of St Mary-at-Hill

Senior Porters and Fishmongers of Billingsgate

Frank sweeps up the parsley at the end of the service

The cobbled hill leading down from the church to the old Billingsgate Market

Frank David with the “bobbin” first worn by his grandfather Jim David at Billingsgate in the 1890s

Photographs copyright © Ashley Jordan Gordon

You may also like to read about

Ruth Franklin At House Mill

I first came across artist Ruth Franklin‘s work in Whitechapel in 2015, when she displayed her cardboard sculptures of sewing machines and hairdressing tools, reflecting her family’s history in these trades in the East End.

‘My work is about the importance of household artefacts and family professions in uncovering childhood memories and family history,’ says Ruth.

‘I have been reflecting on my grandparents, who fled Poland in the early 1900’s, to settle in the East End of London, where they set up a tailors workshop. Looking too at my father’s profession as a women’s hairdresser, I have been creating tailoring and hairdressing ‘objects’, both real and imaginary, through sewn paper constructions, and amalgamated workshop and hairdressers tools.’

Now Ruth is showing her new sculptures of hand tools in a joint exhibition with Sara Radstone & Kate Starkey at House Mill on Three Mills Island in Bromley-by-Bow from Wednesday 9th – Sunday 13th October. All are welcome at the private view on Thursday 10th, 6–8:30pm.

The spectacular eighteenth-century House Mill is Europe’s largest tidal mill and, if you have never visited, this is an ideal opportunity.

Power drill (2019)

Hand drill (2019)

Hammer (2019)

Tape Measure (2019)

Sewing machine (2015)

Iron (2015)

Hairdryer (2015)

Hairdressing tools (2015)

Equipment (2015)

The Salon (2015)

Tools for the salon (2015)

Curling machine (2015)

Manya (2015)

Alfy in May, mother’s brogue (2015)

Artwork copyright © Ruth Franklin

You may also like to read about

On Photographing Facades

I write about the experience of photographing facades in today’s excerpt from THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM

We only have to raise the last £1000 now to publish this book on 31st October. Please click here if you are able to help

You can also offer support by ordering a copy in advance for £15. Click here to preorder

Eighteenth century house in Norton Folgate facaded by British Land

I am grateful to you the readers who alerted me to examples of façadism across the capital this summer, sending me on ‘façade safaris’ to compile the collection of trophy specimens which comprise my book. This photographic quest took on its own life and I must confess I sometimes took guilty delight in discovering those bizarre examples which offered the most photogenic possibilities.

Evidently, when the discussion takes place between developers, architects, planners and conservationists a certain nuance enters the debate too. It is in the nature of human beings to seek compromise when negotiating. The questions arise – ‘Surely it is better to keep the façade at least?’ versus ‘What is the point in keeping just the façade, why not get rid of the old building entirely?’ Yet this is looking at the question from the wrong direction. The real question that should be asked is ‘What is the point in keeping just the façade, why not simply keep the whole building?’

I hope my pictures clarify this debate by demonstrating how wrong the practice of façadism is and how, in each case, the original building should never have been destroyed. I defy anyone to look at this gallery of notorious façades in my book and not be appalled.

These have been years of accelerating development in the capital, with old buildings vanishing and new buildings appearing as the city transforms before our eyes. This environment has allowed the creeping plague of ghastly façadism to spread almost invisibly across the capital, while the attention of the populace has been distracted by the exotic new buildings emerging on the skyline. By their nature, these subtle reconfigurations are less visible than the more obvious visual changes even if the implications are no less significant.

When the façade of a building is preserved, there is a sense that the reality of the change of use of the site is denied, even if the mutation of the building is obvious.

The prevalence of façadism has coincided with the growth of digital culture and our fascination with the virtual as an alternative to the temporal world. When someone walks down the street with a mobile device in hand, they are not paying any attention the buildings or the world around them. People delight to curate their social media with attractive images of themselves, their friends and their pastimes, without much regard to whether or not this is a true picture of their lives.

In all societies, it is the purpose of culture to mediate between appearance and reality. It suits many people not to look too closely at the world around us and exist within a bubble, ignoring inconsistencies and believing half truths. My book is written at a strange moment when the most successful politicians are also the biggest liars. When old buildings speak to us, they tell troubling stories of past aspirations, of deprivation and of struggle, of industry and of privilege. I can understand how it can be easier to live with the surface of history and to ignore the changes that are happening around us in the present day. Façadism suits our times very well, it is indeed – as British Land claim – our ‘kind of authenticity.’

6 Palace Court, Bayswater Rd, Hyde Park, W2

Dating from 1892, this elegant mansion facing Hyde Park was de- signed by Carlos Edward Arthur Ryder in the style of the Aesthetic Movement and built by Holloway Brothers. It comprised four storeys plus mansard roof with gable pitched dormers, and a chamfered bay and arched recessed third floor, with attractive terracotta window dressings throughout.

Buckingham Gate, Westminster, SW1

This terrace of Grade II listed town houses opposite Buckingham Palace was probably designed by Sir James Pennethorne, c.1850–55. They are faced in stucco with Italianate details, comprising four tall storeys plus basements and dormered mansards. Each house is three windows wide with large Doric columned porticos and recessed plate glass sashes.

American Embassy, 30 Grosvenor Sq, Mayfair, W1

The American Embassy London Chancery Building was designed by Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen and constructed in the late fifties, opening in 1960. A gilded aluminium eagle by Theodore Roszak, perched on the roof with a wingspan of thirty-five feet, distinguishes this London landmark.

The building has nine storeys, of which three are below ground. Grade II listed, it is considered to be a classic of modern architecture in the twentieth century.

The United States paid a peppercorn rent to the Duke of West- minster for use of the land and, in response to an American offer to buy the site outright, the Duke requested the return of his land confiscated after the American Revolutionary War, namely the city of Miami.

Only the façade of Eero Saarinen’s building stands now, pending redevelopment as a luxury hotel.

The Anti-Gallican, 155 Tooley St, Bermondsey, SE1

The Anti-Gallican Society was founded around 1745 in response to the perceived cultural invasion of French culture and goods. The Society flourished in the Seven Years’ War of 1756–1763 and the Napoleonic Wars of 1799–1805, persisting through the nineteenth century.

Dating from before 1822, this pub retained its xenophobic title until it closed in 2006, before succumbing to a nameless office development in 2011.

Empire Cinema, 56–61 New Broadway, Ealing, W5

The Empire Cinema was designed by John Stanley Beard in an Italian Renaissance style. It was one of a pair of near identical theatres which were built by Beard for Herbert Yapp in 1934. The other was in Kentish Town and both were taken over by Associated British Cinemas (ABC) within a year of opening. Each had façades dominated by eight tall columns with a double row of windows between the inner six, and seated 2,175 people on two levels. The Empire closed in 2008 and was demolished in 2009 when the doors were installed in its counterpart in Kentish Town to replace ones lost over the years.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY FOR £15

“As if I were being poked repeatedly in the eye with a blunt stick, I cannot avoid becoming increasingly aware of a painfully cynical trend in London architecture which threatens to turn the city into the backlot of an abandoned movie studio.”

The Gentle Author presents a humorous analysis of facadism – the unfortunate practice of destroying an old building apart from the front wall and constructing a new building behind it – revealing why it is happening and what it means.

As this bizarre architectural fad has spread across the capital, The Gentle Author has photographed the most notorious examples, collecting an astonishing gallery of images guaranteed to inspire both laughter and horror in equal measure.

You may also like to take a look at

Philippa Stockley’s Restoration Stories

After reporting on London homes and their owners in the Evening Standard for twenty years, Philippa Stockley has written RESTORATION STORIES, a book about old, mainly Georgian, houses and the heroic souls who saved them

A back yard in Spitalfields

Raised in suburban Surrey, I dreamed of London. Mine was a romantic, book-provoked dream with a twinge of David Copperfield, but many of us rebel against what we knew as children. Though whether I would rebel if I had been raised in a castle or an old rectory was never tested, for ours was an ordinary family house with a big garden.

It was a perfect environment to nurture fantasies of grandeur, enriched by novels. Fantasies that usually included a Georgian house with a gravel sweep and tall windows, or something resembling a house in a film or television adaptation. Always old, often grand, but sometimes a decrepit house with sun-shafted dust and elegant mystery. It made no difference that much of the allure was created by set dressers. For me, beauty – however achieved – has always been the thing.

My actual experience of London was limited to thrilling rare excursions — for fireworks or to feed the ducks in St James’s Park on a snatched lunch hour with my father. Rareness and desirability so often go together.

Eventually I inveigled myself into London, staying in small or transitory places until I won a scholarship to study clothing history at the Courtauld Institute. During my second year, I shared a modest Georgian house in Eel Brook Common with other students. Of aged London stock with a somnolent flagged back yard, it was the first Georgian house I lived in. While some rooms were small and at dusk it could be gloomy, it was lovely and felt completely right.

While studying, I designed and made the costumes for a production of Edward Bond’s Restoration, hammering them out on a miniature sewing machine. My budget was tiny, but I had heard of street markets in the East End. Rumour had it that there were great shed-like warehouses selling heaps of tat in glorious abundance and old clothing emporia, and murky carparks converted into seas of wonder, to navigate sustained by bagels and hot coffee.

For a few ice-sodden Sundays I set out at dawn and bought dodgy mink and rabbit tippets, and boxes of military buttons later safety-pinned to waistcoats and breeches. But I also encountered a clutch of streets whose derelict beauty was like a double-handed slap. It was a very cold winter. My memory of that time sparks with ice. Those cobbled streets, Fournier, Wilkes, Princelet — names themselves romantic — appeared steel-grey, frozen, sprinkled with hoarfrost and fairy-dust in equal measure. Windows were broken or boarded, timber and lead porticos were decaying, yet they were the most magical houses and the most beautiful streets I had ever seen. Walking among them was like walking through the pages of a forgotten book or stepping into a faded postcard. In memory they smouldered, the colour of ashes, yet lay restless in my mind and broke into my heart. Even if I could not afford one, I never forgot them.

Later, others bought and restored them, several of which now smile gravely from the pages of my book. They feel like old friends. All different and with strong personalities. Now that they have simmered in my heart for years, I have tried to give a glimpse of them and of the people who saved them.

The accounts that their owners gave of restoring their homes were fascinating and often funny. Many were wry or poignant, all were passionate. All talked as if their houses were alive – which they are – and as if they had distinct characters – which they do. I believe people who adopt these houses are the same sort who go to animal shelters in search of a small manageable dog and come away with two former greyhounds – one lame – a blasphemous parrot and an old, lunatic cat. The determination to save, to nurture and restore, mixed with a dollop of eccentricity, is always there. A warmth, a largeness of spirit, much generosity, a hint of genial lunacy. These are the characteristics of those who save old houses.

When I write about homes in the Evening Standard, I always write about the house and its owner as inseparable, which makes every story unique. But Georgian houses are special: not only because of their age but because of their grace.

When describing that grace, proportions are often mentioned: the ratio of glazing to brickwork, the pattern of mouldings, the measure of dado-panelling to wall height and the form of the panels. All a given. Yet it is the millions of small constituents, making up the complex that fascinate me more – all the handmade things that together, bit by bit, become a house. Grace slumbers ineffable in every one, from the humblest, the bricks and the lime mortar joining them, to the slow-grown, hand-sawn timber joists, the hand-cut slate tiles or hand-moulded clay pantiles. Then, glass blown white hot and miraculously flattened, bubbling, for window panes, plaster smoothly laid over hand-cut laths, and — oh! — hand- or bucket-mixed paint. Paint mixed to recipes passed from one painter to the other. Very simple for plain colours: the quotidian slubs and duns and off-whites, the quick cheap fake mahogany and pleasant ochres. But also, colours mixed by eye, practice and judgement, by the skill that comes with repetition. Paints mixed with knowledge, not by a machine – made with oil for longevity and satisfying sheen, to protect but also to add gentle tones made with natural earth pigments.

Some of the houses I have written about are nearly three hundred years old – and one is much older – yet their inhabitants find that life with electricity, gas and wi-fi sits well alongside Georgian beauty. What unites these people is that they put beauty first. Their houses share similar temperaments, yet each is completely different. And in every case its beauty speaks for itself.

I enjoy the fact that many were built on just a few courses of bricks. Their neighbours, their half-basements, and their solid but flexible flagged floors of thick stone laid directly on to sand or dirt hold them up effectively – supplemented occasionally with lengths of steel today. They prove that there are economical and renewable ways to construct homes compatible with modern life. If we built them now, they could stand into the twenty-fourth century.

The smallest were usually dubbed ‘fourth-rate.’ These were often narrow terrace houses of three or four floors including attic and half-basement. Today, it is a perfect size for a couple or young family. Yet some are just fourteen-foot wide — my own is a case in point. It reminds me of an upended caravan. It is not large yet it is ample and this graceful sufficiency is another Georgian trick, unlike later Victorian two-up-two-downs, which introduced meanness and a rather glum squatness. Houses like mine demonstrate an economical use of the plot with a light footprint both actually and metaphorically, while retaining the proportions of their grand cousins. These fourth-rate houses are the soot-blackened town mice, the London sparrows.

They also remind anyone who makes things that will not last or cannot be recycled, or who continues to argue in favour of demolition and shoddy, short-term building, that houses made of brick, lime, timber, and stone live, breathe and move, and if left alone will do so for a very long time. They shift and whisper, creak and murmur, particularly on London clay. Architects and planners should study them afresh.

In Elder St

In Mile End

In Elder St

In Fournier St

In Whitechapel

In Elder St

In Whitechapel

In Elder St

In Cable St

In Fournier St

In Fournier St

In Elephant & Castle

On the Isle of Sheppey

In Elephant & Castle

In Whitechapel

In Cable St

Photographs copyright © Charlie Hopkinson

RESTORATION STORIES by Philippa Stockley is published by Pimpernel Press today

You may also like to read about

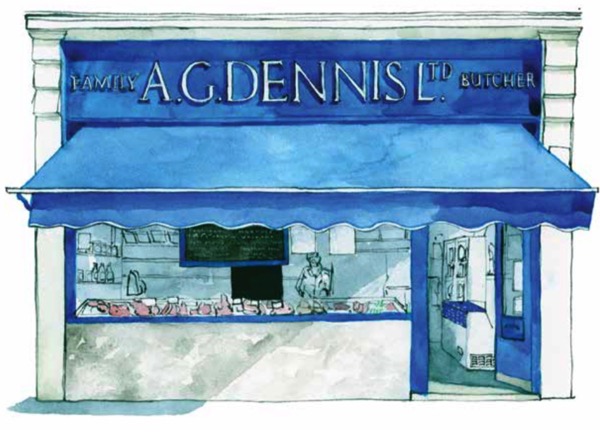

Eleanor Crow’s Butchers

An exhibition of Eleanor Crow’s watercolours of classic London shopfronts featuring many paintings from her book SHOPFRONTS OF LONDON, In Praise Of Small Neighbourhood Shops is at Townhouse in Fournier St from Friday 4th October. You are all invited to the opening and book launch this Thursday 3rd October from 6:00pm.

Eleanor will giving an illustrated lecture at Wanstead Tap on Wednesday 9th October, showing her pictures and telling the stories of the shops. Click here for tickets

Click here to order a signed copy of Eleanor’s book for £14.99

W. A. Down & Son, The Slade, Plumstead

“Butchers have enjoyed an unlikely renaissance recently due to an increased interest in provenance and a suspicion of processed meat in the light of the horse meat scandal. Consequently, customers are now willing to spend more to buy better quality meat despite the presence of a nearby supermarket. A butcher can sell a range of cuts for all budgets, as well as offering advice on how to prepare and cook the meat. The rise of the celebrity chef has also contributed, encouraging people to seek out specialist and traditional butchers, and to buy meat in the old-fashioned way.” – Eleanor Crow

M & R Meats, St John St, Clerkenwell

Hussey’s, Wapping Lane

J Whenlock, Barking Rd, Plaistow

The Cookery, Stoke Newington High St

W. D. Chapman, High Rd, Woodford Green

The East London Sausage Company, Orford Rd, Walthamstow

The Butchers Shop, Bethnal Green Rd

J. Geller, High Rd, Leytonstone

Meat N16, Church St, Stoke Newington

A. G. Dennis, High St, Wanstead

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £14.99

At a time of momentous change in the high street, Eleanor’s witty and fascinating personal survey champions the enduring culture of Britain’s small neighbourhood shops.

As our high streets decline into generic monotony, we cherish the independent shops and family businesses that enrich our city with their characterful frontages and distinctive typography.

Eleanor’s collection includes more than hundred of her watercolours of the capital’s bakers, cafés, butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers, chemists, launderettes, hardware stores, eel & pie shops, bookshops and stationers. Her pictures are accompanied by the stories of the shops, their history and their shopkeepers – stretching from Chelsea in the west to Bethnal Green and Walthamstow in the east.

A Walk With Shloimy Alman

Let us join photographer Shloimy Alman as he wanders the streets of the East End in the seventies accompanied by the Yiddish poet Avram Stencl. Alman’s photographs are published for the first time here today and can be seen in a one day exhibition at Sandys Row Synagogue next Sunday 6th October, 11:00am-6:00pm. Click here to book a ticket

Photographs copyright © Shloimy Alman

You may also like to take a look at

Shloimy Alman, Photographer

Rachel Lichtenstein introduces the photographs of Shloimy Alman, which are published here for the first time and will be the subject of a one day exhibition at Sandys Row Synagogue next Sunday 6th October, 11:00am-6:00pm. Click here to book a ticket

Harvey Rifkind, president of the synagogue, told Rachel about this collection of unseen photography taken in the seventies and, in May this year, Harvey and Rachel visited Shloimy in Israel where Rachel interviewed him and scanned over three hundred of his pictures.

Rachel’s piece features excerpts from her interview with Shloimy.

Shloimy Alman was born in Manchester in 1950, three years after his Polish Jewish parents arrived in England in 1947. His father Moishe came from Tarłów, a small town half way between Krakow and Warsaw. He taught Yiddish before the war and became active in the Bund in Wlotzlawek. His first wife and child were killed during the Holocaust. Moishe spent the war years in a Siberian labour camp working as a lumberjack.

After the war Moishe was instrumental in starting the first Yiddish school for the surviving Jewish children in Walbrzych, which is where he met his second wife Sara Scheingross, Shloimy’s mother, and her daughter Eva, aged six. In 1947, Sara and Moishe married and left for Manchester where Moishe’s two brothers had settled before the First World War. ‘For my mother after coming from pre-war Warsaw which was, in terms of style akin to Paris, Manchester was a disappointment to her,’ Shloimy recalled.

His parents craved the vibrant Yiddish culture of Poland which was largely missing in post-war Manchester, although there were still a number of Jewish shops and businesses, particularly in the Cheetham Hill Rd, High Town and Strangeways areas. Shloimy would accompany his mother on shopping trips. ‘There were very few children of my pre-school age then who were speaking Yiddish so I was an attraction,’ he said. ‘When we went to the grocer, he’d shove his hand in the barrel and shlept out a sour cucumber for me. If we went to the deli, I’d have a stick of vursht. When we went to buy the live chicken, before taking it to the slaughterhouse, the owner would find a warm egg, then poke some holes in so I could suck the egg. I was a child celeb, in many ways spoilt rotten by most of the shopkeepers because I spoke to them in Yiddish.’

Shloimy’s Uncle Lazar had a barber’s shop and was involved in Yiddish literary and Zionist circles. ‘He had an amazing Yiddish library upstairs and, despite the fact he was a working man and had no formal education, he was tremendously well read. When the Yiddish theatre came to Manchester the actors would be put up on the barber’s chairs to sleep overnight and served the most magnificent breakfast by Lazar in the morning.’

Lazar introduced Shloimy’s parents to the monthly Yiddish magazine Loshn un Lebn (Language & Life), edited and compiled by London’s foremost Yiddish poet, another Polish émigré, Avram Stencl. They took a monthly subscription ‘and looked forward to its arrival with tremendous pleasure, reading the magazine from cover to cover.’ Moishe was soon writing articles in Yiddish for the magazine. ‘My father never went to London and Stencl never came to Manchester but they regularly wrote to each other.’

After Moishe died in 1964, ‘even when my mother had no money, she still kept up her subscription and read the magazine religiously’ said Shloimy. One Saturday afternoon she went to London and sang at the Saturday afternoon Friends of Yiddish meetings, which Stencl had established in 1936 after his arrival from Poland. Shloimy grew up hearing stories about the legendary Yiddish poet and years later after his parents had died, he wrote to the poet and asked if they could meet.

Like the Manchester Jewish shopkeepers of his childhood, Stencl was delighted to hear from someone of Shloimy’s generation who was a fluent Yiddish speaker and he invited the youth worker in his twenties from Manchester to meet him in Whitechapel. They met for the first time in the summer of 1977 in the ABC café near Whitechapel Station. ‘It was the place where quite a few of the people would meet before the Saturday afternoon meetings to have tea and cake, then they would all walk off together to Stepney Green to Beaumont Hall, where the meetings took place.’

The poet was already in his mid-seventies by then. ‘He cut an impressive figure,’ said Shloimy, ‘with his electric blue eyes, trilby hat and well-cut but shabby suit. He always had a copy of Loshn un Lebn under his arm and was always trying to hawk it.’

On their first walk, Stencl led him to Bevis Marks Synagogue in the city, the oldest synagogue in London, established by Sephardi Jews in the seventeenth century. ‘He walked very quickly for an old man I had trouble keeping up with him. As we walked and talked, in Yiddish of course, he pointed out places on the way, where the Jews Free School had been, the site of the Jewish Soup Kitchen, Bloom’s restaurant on Whitechapel High St and the many small synagogues, which were still operating.’ Shloimy was amazed by the amount of Jewish institutions, shops and people still evident. ‘People kept telling me the Jewish East End was dead but for me, coming from Manchester, it was buzzing with life and activity.’

They passed run-down tenement blocks and stopped briefly at Whitechapel Library, known as ‘the university of the ghetto.’ After their walk, Shloimy went with Stencl to the Friends of Yiddish meeting. There were about twenty people there who were all very welcoming. After this first, visit Shloimy began attending these meetings regularly whilst visiting his parents-in-law in London. ‘I wanted to be in that atmosphere that my parents so loved, to hear Yiddish literature being spoken and talked about again. It was most important. Stencl invariably opened with one of his poems, then he would discuss anything from the Torah portion of the week to a current piece of news. Others sang, really put their soul into it, lots of different people got up to speak, read, anything went, as long as it was in Yiddish.’

After his initial walk around Whitechapel with Stencl, Shloimy started exploring by himself before the Shabbat meetings, often drifting around the streets, coming across things by accident. ‘Knowing that places like Commercial Rd were important, I’d wander along and see a Jewish shop name and photograph it.’ He spent days recording Jewish life, from shuls to deli’s, shops, market stalls and traders. He recorded the textile-trimming merchants. ‘I love this picture of three gentlemen with trilby hats selling cloth. My father was a tailor’s son, that’s how he always described himself. My father sewed beautifully, my grandfather’s eldest son became a tailor and his eldest son became a tailor, and I remember going to buy cloth with my father and watch the way he felt it, stretched it, it was an art, a science.’

He recorded kosher poulterers in Hessel St. ‘Shop after shop, stalls with chickens plucked and hanging from a barrow, they were all surviving, all doing business, it was still a rich Jewish landscape.’ He took photographs of kosher wine merchants, the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre – ‘I remember some of the actors who played there coming to Manchester and staying at my uncle’s house’ and the site of the Federation of Synagogue offices in Greatorex St, where he visited the Kosher Luncheon Club run by Connie Shack in the same building where ‘You got a good meal for a reasonable price – it had a specific European style.’

He took slides of the Jewish bakeries – Free Co, Cohen’s, Kossoff’s, Grodzinski’s and beigel shops in East London at the time. ‘They were all friendly, loved me coming in and chatting in Yiddish and taking a picture.’ He went into the Soup Kitchen on Brune St, which was sending out pre-packed food ‘Jacobs Crackers, eggs, Dairylea cheese, spaghetti’ to elderly Jews living in the area.

On Brick Lane, he photographed Jewish booksellers, newsagents, textile merchants. ‘All these places existed, everything the community needed – it told me how large the community still was. It wasn’t on its last legs, it was vibrant.’ On Cheshire St he saw the work of Jewish cabinet makers outside their workshops and during one visit he managed to get inside the Cheshire St Synagogue, ‘which was the most remarkable find, it was a Shabbat and the door was slightly open so I went inside and saw all this beautifully lathed woodwork done by the cabinet makers of the street. It was a working man’s shul, around the walls the donations were listed, some as little as two guineas. They made this place with their own hands. And because of the wood the synagogue had this warm, welcoming atmosphere. When I went there, there were exactly ten men praying, they had the most magnificent Kiddush, almost a full meal at the end of the service, arranged for them by the Bangladeshi caretaker because nobody lived near the shul, and they all had a long walk back home.’

He photographed the entrance to Black Lion Yard, once known as ‘the Hatton Garden of the East End’ because of all the jewellery shops there, although most of the street and shops had been demolished by then. He took pictures of the Whitechapel Waste, of the market stalls and street life, of Stencl selling his magazine to an alter bubby (old grandmother), the London Hospital, the nearby Brady St dwellings, ‘dark and ominous looking tenements which were pulled down soon after.’ He explored the back streets, visited little shops, tobacconists, market stalls and Jewish delis. ‘Roggs was my favourite, he’d always be in that old vest, sticking his great hairy arms into a barrel of cucumbers he pickled himself.’ He photographed the window of the room in Tyne St where ‘Sholem Aleichem stayed on his way to America from Odessa.’ Most of the time Shloimy walked alone but sometimes Stencl would join him. On one of these walks Stencl took him to Narod Press on Cavell St where Loshn un Lebn was printed and introduced him to the typesetter, a shy orthodox man who allowed Shloimy to take his portrait.

Overtime Shloimy became real friends with Stencl who he described as ‘a Hasid of Whitechapel. The place was good to him, it gave him a home, it gave somewhere he could write in peace (apart from the Blitz of course), he was always grateful for that, his poetry expresses his love for the place.’

Shloimy also fell in love with the area and he documented what he saw. He said, ‘I am not a photographer, I make no claim. The reason that I started this is I wanted to be able to show my children about Jewish life in England before I immigrated to Israel. It was obvious to me that what I was looking at was soon to vanish. It might be because I was an outsider that I saw this so acutely or because I had already witnessed this disappearance of Jewish life in Manchester. For an intense period of time I photographed what I considered important landmarks and eating places of Jewish London.’

His photographs capture the era absolutely and survive as a unique record of a disappeared world.In 1978 Shloimy, his wife Linda and twins made Aliya to Israel, and since December 1982 he has lived in the collective village of Kfar Daniel.

Photographs copyright © Shloimy Alman

You may also like to take a look at