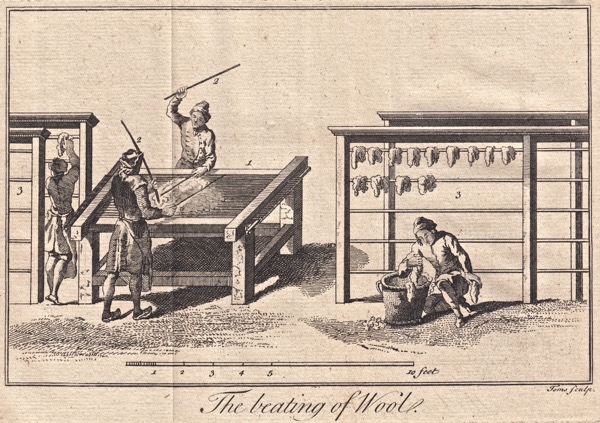

The Principal Operations Of Weaving

These copperplate engravings illustrate The Principal Operations of Weaving reproduced from a book of 1748 in the collection at Dennis Severs House. Many of these activities would have been a familiar sight in Spitalfields three centuries ago.

Ribbon Weaving

Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate House, Spitalfields, E1

You make also like to read about

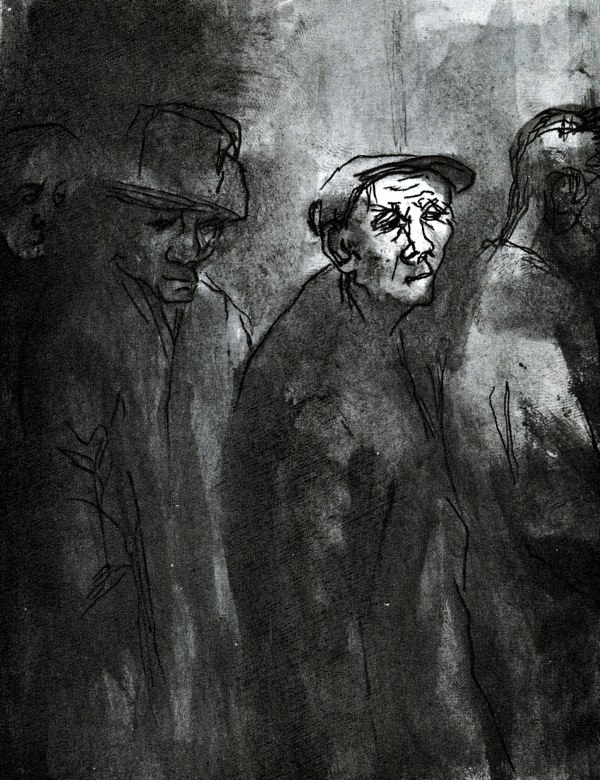

Eva Frankfurther, Artist

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1959, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end, the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images copyrigh t© Estate of Eva Frankfurter

You may also wish to take a look at

Gillian Tindall’s Lost People

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY FOR £10

Remembering writer and historian Gillian Tindall who died in October, I am publishing her meditation upon the paradox of photography – that brings us closer to history yet also separates us from the past.

Boulevard du Temple, Paris, by Louis Daguerre, 1838

It is over a hundred and fifty years years since photographic portraits ceased to be an exotic rarity and began to make their way into the homes of those with a little money to spare. And it is over a hundred years since the first cinemas opened to show flickering silent movies.

For all the centuries before, nearly all people and places that had gone were lost forever, surviving only in the memories of those who would themselves disappear in turn. As each generation died, another tranche of the past slipped quietly into the vast pool of the irretrievable. The faces of kings and a few others rich or famous enough to be painted from life were preserved. But the vast majority of men and women, however prosperous, however active and handsome, however busy their lives, simply became – as the Bible quietly warns – ‘as if they had never been born’.

The tiny minority whose names survived because their stories were told and re-told were typically portrayed in clothes and circumstances that belonged to the time of telling rather than those of their own date. We are used to seeing Mary the Virgin in medieval dress and Christ garbed something like a travelling friar of the same era. It does not bother us that the Palestinian garments of two thousand years ago may have been rather different.

Similarly, our Elizabethan ancestors, looking back into history, were quite at ease imagining that people had always lived and thought more or less as they did. Actors wore the contemporary clothes of their own time rather than ‘period costume.’ The battle scenes in Macbeth bear more relation to the Wars of the Roses – which in Shakespeare’s childhood would still have been remembered by the old – than they do to the battles of the Scottish usurper of five hundred years earlier. And the famous dinner, at which Macbeth is alarmed by Banquo’s ghost, resembles an Elizabethan social gathering rather than anything credible in a remote Scottish glen in the Dark Ages.

Today, if we have any acquaintance with history, we understand the past – I will not say ‘better’ but ‘differently.’ We know that our ancestors, though ‘just like us’ in some ways, did not speak or even think like us. They feared things we do not fear and were robust-minded in ways that shock us. We know they had different assumptions from us, different moral imperatives and different expectations. They are Philip Larkin’s ‘endless altered people’, forever walking down the church aisle in the same way – yet not quite the same.

Anyone who has seen They Shall Not Grow Old, the World War One documentary – with clips of the era adjusted to modern film-speed, coloured and with a sound-track added – will know what I mean. In one way, these young men brought back to life again, so many of whom did not survive till 1918, are painfully like our own husbands, brothers, sons. Only, they are not. They are preserved in an eternal moment that brings them close just as it keeps us apart from them. So much about them – their clothes, their weapons, their slang, their bad teeth, their boots, their mannerisms – indicate that it is the irretrievable past we are viewing.

Another remastered film came my way recently, of a journey along the Regent’s Canal in its working heyday, interspersed with fleeting views of surrounding streets. No Camden Lock market then, instead barges loaded with timber and hard-core, slowly pacing horses and men shifting crates. But no thumps and bangs, no clopping of hooves or crash of water into locks, for films were silent then. Instead, elegiac music has been added, even over the glimpses of streets full of trams and open-topped buses. Nothing could emphasise more the fact that, since the film was shot in 1924, all the busy people in hats and long coats, glancing curiously at the camera as they hurry pass, must now be dead.

The same is true of many other street photographs that now fascinate us with their juxtaposition of the familiar and the strange. Yet often they do not quite carry the same emotional charge as random shots. Many twentieth century photographers, in this and other countries, have done what sketchers and engravers of street-scenes did before them: they have picked out distinctive street-people – traders, beggars, down-and-outs, well-known local characters – as representative figures. Yet the very fact of being singled out makes these people subtly special.

It is the completely incidental figure, often apparently unaware of the camera, in a picture otherwise taken as a streetscape, that stirs in me the feeling that I really am being offered a brief entry into the past. The blessed Colin O’Brien’s views of Clerkenwell and Hackney in the later decades of the twentieth century are occasionally of this kind. So too are some of the East End scenes of John Claridge, though much of the dereliction he recorded is essentially unpeopled. In just a few shots – a lone man in a mackintosh riding a bicycle though a waste-land, a gaunt-faced workman in a suit looking round warily from his work in a yard – I get the eerie sense of being close to a vanished individual’s reality.

And this is true of the celebrated earliest street photo of all, which was taken by Louis Daguerre from a high window of a Paris boulevard in 1838. The camera’s shutter had to open for a long exposure which renders passing carriages and pedestrians as only faint blurs. Yet clearly visible is one man, because he was standing still to have his boots cleaned. He was the first person ever to be photographed. He did not know it. And we have no idea who he was.

Accident at the junction of Clerkenwell Rd and Farringdon Rd, 1957. Photo by Colin O’Brien

E16, 1982. “He’s going home to his dinner.” Photo by John Claridge

You may also like to read about

The Metropolitan Machinists’ Company Catalogue

In recent years, I have eschewed public transport and become a committed cyclist, so I was delighted to discover this 1896 catalogue for The Metropolitan Machinists’ Co, yet another of the lost trades of Bishopsgate, reproduced courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Signs Of Life

First Snowdrops in Wapping

Even now, in the depths of Winter, there is plant life stirring. As I travelled around the East End over the past week in the wet and cold, I kept my eyes open for new life and was rewarded for my quest by the precious discoveries that you see here. Fulfilling my need for assurance that we are advancing in our passage through the year, each plant offers undeniable evidence that, although there may be months of winter yet to come, I can look forward to the spring that will arrive before too long.

Hellebores in Shoreditch

Catkins in Bethnal Green

Catkins in Weavers’ Fields

Quince flowers in Spitalfields

Cherry blossom in Museum Gardens

Netteswell House is the oldest dwelling in Bethnal Green

Aconites in King Edward VII Memorial Park in Limehouse

Cherry Blossom near Columbia Rd

Hellebores in Spitalfields

Spring greens at Spitalfields City Farm

The gherkin and the artichoke

Cherry blossom in Itchy Park

Soft fruit cuttings at Spitalfields City Farm

Seedlings at Spitalfields City Farm

Cherry blossom at Christ Church

The Triumph Of Populations Bakery

It is my pleasure to publish these edited excerpts from this piece by Julia Harrison, author of the fascinating literary blog THE SILVER LOCKET. I am proud that Julia is a graduate of my blog-writing course.

There are only a few places available now on my course HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ on 7th & 8th February. Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to enrol.

George’s Galette des Rois

Spitalfields Life readers will already know about George Fuest’s Populations Bakery. In the past, I have collected pastries from George’s home on Fournier St but the discovery that he was offering Galettes des Rois at his new bakery at Corner Shop in Arundel St was just too tempting. On Saturday, I made my way down to the Embankment, almost next door to Temple Place, to collect one.

I was met with apologies from one of George’s team of bakers, Huey. My galette was still in the oven: would I sit down, have a cup of coffee and taste a slice? I eagerly agreed and when there was a pause in the morning rush, Huey took a few moments to talk to me. He started by explaining the reason for the name ‘Populations Bakery’.

‘George uses heritage wheat populations which are mainly ancient heritage grains, Populations-diverse wheat is where you have got lots of different species of wheat, meaning that the soil is in far better condition. If you go to these fields you can see it clearly because rather than weeds being around knee height the crop is up to waist height: so much healthier for you but also for the soil and the landscape.

He uses a lot of stone-milled flour in his pastries: stone-milled flour keeps all the properties of the wheat as opposed to regular sifted milled flour. It means that the pastries have a darker colour because there are more sugars, more nutrients to caramelise, which means more flavour.’

Then Huey handed me a box containing a delicate pastry that would not look out of place in a patisserie in Paris.

‘This is the perfect example of what he does: unbelievable technique as well as the provenance of the ingredients. The technique is cross lamination: if you are making a dough for pastries you laminate butter and then the dough. Once that is all done you slice it very thinly and then twist the segments ninety degrees, and then re-laminate it which means you have more texture and better flavour as well.

Then the clementine: you have candied clementine on top and then clementine creme inside with creme fraiche. The clementine comes from Vincente Todoli, grown just outside Valencia which has a long history of citrus farms. He moved away, became an art dealer, travelled the world, fell back in love with citrus and now has created this citrus sanctuary in Valencia. It has the biggest collection of citrus trees from around the world and they have all started cross breeding with each other and making new varieties. It is like a museum, but for citrus.’

I look up Vincente Todoli and discover that he was not just any old art dealer, but one-time director of Tate Modern. His Todoli Citrus Fondacio preserves rare citrus varieties for future generations.

When I remark on George achievement in scaling up his bakery from his garden shed in Fournier St, Huey says ‘I try and get the message through to as many guests as I can, such a variety of people come through these doors.’ The fact that my galette was still in the oven turned out to be a moment of serendipity. I am indebted to Huey for taking the time to share the philosophy which brings producer and baker together in such fine style.

George’s Clementine Creme Fraiche Croissant

Populations Bakery goods on display at Corner Shop

Patricia Niven‘s portrait of George Fuest from 2023 in Fournier St

You may also like to read about

C A Mathew’s Spitalfields

In Crispin St, looking towards the Spitalfields Market

On Saturday April 20th 1912, C.A.Mathew walked out of Liverpool St Station with a camera in hand. No-one knows for certain why he chose to wander through the streets of Spitalfields taking photographs that day. It may be that the pictures were a commission, though this seems unlikely as they were never published. I prefer another theory, that he was waiting for the train home to Brightlingsea in Essex where he had a studio in Tower St, and simply walked out of the station, taking these pictures to pass the time. It is not impossible that these exceptional photographs owe their existence to something as mundane as a delayed train.

Little is known of C.A.Mathew, who only started photography in 1911, the year before these pictures and died eleven years later in 1923 – yet today his beautiful set of photographs preserved at the Bishopsgate Institute exists as the most vivid evocation we have of Spitalfields at this time.

Because C.A.Mathew is such an enigmatic figure, I have conjured my own picture of him in a shabby suit and bowler hat, with a threadbare tweed coat and muffler against the chill April wind. I can see him trudging the streets of Spitalfields lugging his camera, grimacing behind his thick moustache as he squints at the sky to apprise the light and the buildings. Let me admit, it is hard to resist a sense of connection to him because of the generous humanity of some of these images. While his contemporaries sought more self-consciously picturesque staged photographs, C.A.Mathew’s pictures possess a relaxed spontaneity, even an informal quality, that allows his subjects to meet our gaze as equals. As viewer, we are put in the same position as the photographer and the residents of Spitalfields 1912 are peering at us with unknowing curiosity, while we observe them from the reverse of time’s two-way mirror.

How populated these pictures are. The streets of Spitalfields were fuller in those days – doubly surprising when you remember that this was a Jewish neighbourhood then and these photographs were taken upon the Sabbath. It is a joy to see so many children playing in the street, a sight no longer to be seen in Spitalfields. The other aspect of these photographs which is surprising to a modern eye is that the people, and especially the children, are well-dressed on the whole. They do not look like poor people and, contrary to the widespread perception that this was an area dominated by poverty at that time, I only spotted one bare-footed urchin among the hundreds of figures in these photographs.

The other source of fascination here is to see how some streets have changed beyond recognition while others remain almost identical. Most of all it is the human details that touch me, scrutinising each of the individual figures presenting themselves with dignity in their worn clothes, and the children who treat the streets as their own. Spot the boy in the photograph above standing on the truck with his hoop and the girl sitting in the pram that she is too big for. In the view through Spitalfields to Christ Church from Bishopsgate, observe the boy in the cap leaning against the lamppost in the middle of Bishopsgate with such proprietorial ease, unthinkable in today’s traffic.

These pictures are all that exists of the life of C.A.Mathew, but I think they are a fine legacy for us to remember him because they contain a whole world in these few streets, that we could never know in such vibrant detail if it were not for him. Such is the haphazard nature of human life that these images may be the consequence of a delayed train, yet irrespective of the obscure circumstances of their origin, this is photography of the highest order. C.A.Mathew was recording life.

Looking down Brushfield St towards Christ Church, Spitalfields.

Bell Lane looking towards Crispin St.

Looking up Middlesex St from Bishopsgate.

Looking down Sandys Row from Artillery Lane – observe the horse and cart approaching in the distance.

Looking down Frying Pan Alley towards Crispin St.

Looking down Middlesex St towards Bishopsgate.

Widegate St looking towards Artillery Passage.

In Spital Square, looking towards the market.

At the corner of Sandys Row and Frying Pan Alley.

At the junction of Seward St and Artillery Lane.

Looking down Artillery Lane towards Artillery Passage.

An enlargement of the picture above reveals the newshoarding announcing the sinking of the Titanic, confirming the date of this photograph as 1912.

Spitalfields as C.A.Mathew found it, Bacon’s “Citizen” Map of the City of London 1912.

Photographs courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute