A Couple Of Pints With Tony Hall

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR MY TOURS & BUY GIFT VOUCHERS

Libby Hall remembered the first time she visited a pub with Tony Hall in the nineteen sixties – because it signalled the beginning of their relationship which lasted until his death in 2008. “We’d been working together at a printer in Cowcross St, Clerkenwell, but our romance began in the pub on the night I was leaving,” Libby confided to me, “It was my going-away drinks and I put my arms around Tony in the pub.”

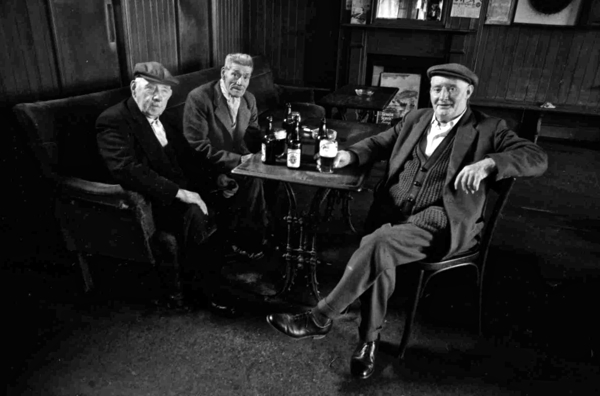

During the late sixties, Tony Hall worked as a newspaper artist in Fleet St for The Evening News and then for The Sun, using his spare time to draw weekly cartoons for The Labour Herald. Yet although he did not see himself as a photographer, Tony took over a thousand photographs that survive as a distinctive testament to his personal vision of life in the East End.

Shift work on Fleet St gave Tony free time in the afternoon that he spent in the pub which was when these photographs, published here for the first time, were taken. “Tony loved East End pubs,” Libby recalled fondly, “He loved the atmosphere. He loved the relationships with the regular customers. If a regular didn’t turn up one night, someone would go round to see if they were alright.”

Tony Hall’s pub pictures record a lost world of the public house as the centre of the community in the nineteen sixties. “On Christmas 1967, I was working as a photographer at the Morning Star and on Christmas Eve I bought an oven-ready turkey at Smithfield Market.” Libby remembered, “After work, Tony and I went into the Metropolitan Tavern, and my turkey was stolen – but before I knew it there had been a whip round and a bigger and better one arrived!”

The former “Laurel Tree” on Brick Lane

Photographs copyright © Estate of Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read

Old Mother Hubbard & Her Wonderful Dog

Courtesy of Jemmy Catnach of Catnach Press, it is my pleasure to publish this early nineteenth century shaggy dog tale of the devoted Mother Hubbard – believed to be by Sarah Catherine Martin

You may also like to read about

Libby Hall, Collector of Dog Photography

At St Botolph’s School House

If you want to know the story of the splendid pair of statues of schoolchildren upon the front of the former School House at St Botolph’s in Bishopsgate, Reg the Caretaker is your man. “When this was a school, these statues used to be in colour – the children repainted them each year – and then we sent them away for a whole year to get all the layers removed,” he explained to me with a sigh. “When they came back, people tried twice to nick them, so then we put them inside but the Council said, ‘They’re listed,’ and we had to send them away again for another year to get replicas cast.”

Old photographs show these figures covered in gloss paint and reduced to lifeless mannequins, yet these new casts from the originals – now that the paint has been removed – are startlingly lifelike, full of expression and displaying fine details of demeanour and costume. The presence of the pair in their symmetrical niches dramatically enlivens the formality of the architecture of 1820 and, close up, they confront you with their implacable expressions of modest reserve. Quite literally, these were the model schoolchildren for the generations who passed through these doors, demure in tidy uniforms and eagerly clutching their textbooks. Their badges would once have had the image of a boy and a sheep with the text, “God’s providence is our inheritance.”

“It’s Coade stone – the woman died with the recipe, but now they’ve rediscovered it again,” added Reg helpfully and – sure enough – upon the base of the schoolboy are impressed the words “COADE LAMBETH 1821.” Born in Exeter in 1733, Eleanor Coade perfected the casting process and ran Coade’s Artificial Stone Manufactory from 1769 at a site on the South Bank, until she died in 1821 aged eighty-eight – which makes these figures among the last produced under her supervision. Mrs Coade was the first to exploit the manufacture of artificial stone successfully and her works may still be seen all over London, including the figures upon Twinings in the Strand, the lion upon Westminster Bridge and the Nelson pediment at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich.

Reg took me inside to show me St Botolph’s Hall, lined with oak panelling of 1725 from a demolished stately home in Northamptonshire, where the two original statues peer out from behind glass seemingly bemused at the corporate City functions which commonly occupy their school room now. The Bishopsgate Ward School was begun in 1820 by Sir William Rawlins, a Furniture Maker who became Master of the Worshipful Company of Upholders and Sheriff of the City of London. In twenty years as Treasurer, he had lifted the institution up from poverty and it opened on 1st August 1821 with three hundred and forty pupils, of whom eighty needy boys and girls were provided with their uniforms.

“They used to be the other way round,” admitted Reg mischievously, indicating the pair of figures on the exterior, “their eyes used to meet but now they are looking in opposite directions.” Yet, given all the changes in the City in the last two centuries – “Who can blame the kids if their eyes are wandering now?” I thought. It was a sentiment with which Reg seemed in accord and which the enterprising Mrs Coade exemplified in the longevity of her endeavours too. “I should have retired years ago but I don’t like sitting indoors and couldn’t stand all that earlobe bashing,” he confessed to me, “I like to be outside doing something.”

In St Botolph’s Churchyard, Bishopsgate – Schoolroom and Sir William Rawlins’ tomb

Original figure coated in layers of paint

Modern replica now in place upon St Botolph’s Hall

Original figure coated in layers of paint

Modern replica now in place upon exterior of St Botolph’s Hall

With layers of paint removed, the original figures now stand inside the hall

Reg the Caretaker at St Botolph’s

Coade stone Nelson pediment at Greenwich

Archive photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

The Stepney School Strike

In the summer of 1971, eight hundred pupils went on strike in Stepney, demanding that their teacher, Chris Searle, be reinstated after the school fired him for publishing a book of their poetry. At a time of unrest, following strikes by postmen and dustmen, the children’s strike became national headline news and they received universal support in the press for their protest.

More than two years later, after the parents, the Inner London Education Authority, the National Union of Teachers, and even Margaret Thatcher, then Education Secretary, came out in favour of Chris Searle, he got his job back and the children were vindicated. And the book of verse, entitled “Stepney Words” sold more than fifteen thousand copies, with the poems published in newspapers, and broadcast on television and read at the Albert Hall. It was an inspirational moment that revealed the liberating power of poetry as a profound expression of the truth of human experience.

Many of those school children – in their sixties now – still recall the event with great affection as a formative moment that changed their lives forever, and so when Chris Searle, the twenty-four-year-old student teacher of 1971 returned to the East End to recall that cathartic summer and meet some of his former pupils, it was an understandably emotional occasion. And I was lucky enough to be there to hear what he had to say.

I grew up in the fifties and sixties, failed the eleven plus and I hated any kind of divisiveness in education, I saw hundreds of my mates just pushed out into menial jobs. So I got into a Libertarian frame of mind and became involved in Socialist politics. I was in the Caribbean at the time of the Black Power uprisings, so I had some fairly strong ideas about power and education. Sir John Cass Foundation & Redcoat School in Stepney was grim. It was a so-called Christian School and many of the teachers were priests, yet I remember one used to walk round with a cape and cane like something out of Dickens.

The ways of the school contrasted harshly with the vitality and verve of the students. As drama teacher, I used to do play readings but I found they responded better to poetry, and I was reading William Blake and Isaac Rosenberg to them, both London poets who took inspiration from the streets. So I took the pupils out onto the street and asked them to write about what they saw, and the poems these eleven-year-olds wrote were so beautiful, I was stunned and I thought they should be published. Blake and Rosenberg were published, why not these young writers? We asked the school governors but they said the poems were too gloomy, so they forbade us to publish them.

I showed the poems to Trevor Huddleston, the Bishop of Stepney, and he loved them. And it became evident that there was a duality in the church, because the chairman of the school governors who was a priest said to me, ‘“Don’t you realise these are fallen children?” in other words, they were of the devil. But Trevor Huddleston read the poems and then, with a profound look, said, “These children are the children of God.” So I should have realised there was going to be a bit of a battle.

There was even a suggestion that I had written the poems myself, but though I am a poet, I could not have written anything as powerful as these children had done. Once it was published, the sequence of events was swift, I was suspended and eight hundred children went on strike the next day, standing outside in the rain and refusing to go inside the school. I didn’t know they were going to go on strike, but the day before they were very secretive and I realised something was up, though I didn’t know what it was.

I didn’t have an easy time as a teacher, it was sometimes difficult to get their interest, and I had bad days and I had good days, and sometimes I had wonderful days. Looking back, it was the energy, and vitality, and extraordinary sense of humour of the children that got you through the day. And if, as a teacher, you could set these kids free, then you really did begin to enjoy the days. It gave me the impetus to remain a teacher for the rest of my life.

I tried to get the kids to go back into the school.

Tony Harcup, a former pupil of Chris Searle’s and now senior lecturer in Journalism at Sheffield University, spoke for many when he admitted, “It was one of the proudest days of my life, it taught me that you can make a stand. It was about dignified mutual respect. He didn’t expect the worst of us, he believed everyone could produce work of value. He opened your eyes to the world.”

During the two years Chris was waiting to be reinstated at the school, he founded a group of writers in the basement of St George’s Town Hall in Cable St. Students who had their work published in “Stepney Words” were able to continue their writing there, thinking of themselves as writers now rather than pupils. People of different ages came to join them, especially pensioners, and they used the money from “Stepney Words” to publish other works, beginning with the poetry of Stephen Hicks, the boxer poet, who lived near the school and had been befriended by many of children.

“Stepney Words” became the catalyst for an entire movement of community publishing in this country, and many involved went on to become writers or work in related professions.“The power to write, the power to create, and the power of the imagination, these are the fundamentals to achieve a satisfied life,” said Chris, speaking from the heart, “and when you look back today at the lives of those in the Basement Writers, you can see the proof of that.”

The story of the Stepney school strike reveals what happens when a single individual is able to unlock the creative potential of a group of people, who might otherwise be considered to be without prospects, and it also reminds us of all the human possibility that for the most part, remains untapped. ” I just want to thank the young people that stood up for me” declared Chris Searle with humility, thinking back over his life and recalling his experiences in Stepney, “How could you not be optimistic about youth when you were faced with that?”

Returning to the East End forty years after the school strike, teacher Chris Searle reads one of the original poems from Stepney Words,”Let it Flow, Joe.”, with some of his former pupils.

You might like to read about

In Old Spitalfields

Catherine Wheel Alley

Bishopsgate Institute has a magnificent collection of nineteenth century watercolours collected by the first archivist Charles Goss, which offer tantalising glimpses of the last surviving tumbledown pantiled tenements and terraces, crooked alleys and hidden yards that once comprised the urban landscape of Spitalfields.

When we think of old Spitalfields, we usually consider the eighteenth and nineteenth century fragments remaining today, yet there was another Spitalfields before this. Before the roads were made up, before Commercial St was cut through, before the Market was enclosed, before Liverpool St Station was built, Spitalfields was another place entirely. When Bishopsgate was lined with coaching inns and peppered by renaissance mansions, Spitalfields was celebrated for the production of extravagant silks and satins, but it was also notorious for violent riots and rebellion, where impoverished families might starve or freeze to death.

Sunday Morning in Petticoat Lane, 1838

Old Red House, Corner of Brushfield St by J.P.Emslie, 1879

Paul’s Head, Crispin St by J.T. Wilson, 1870

The Fort & Gun Tavern and Northumberland Arms, corner of Fashion St by J.T.Wilson

Dunning’s Alley showing Lucky Bob’s formerly Duke of Wellington, Bishopsgate by J.T.Wilson, 1868

Bell Tavern, Bell Yard, Gracechurch St by J.T.Wilson, 1869

Bishopsgate at the Corner of Alderman’s Walk beside St Botolph’s church by C.J.Richardson, 1871

House of Sir Francis Dashwood, Alderman’s Walk, by C.J.Richardson, 1820

Entrance from Bishopsgate to Great St Helen’s by C.J.Richardson, 1871

Devonshire House, Bishopsgate by C.J.Richardson, 1871

The Green Dragon, Bishopsgate, coloured by S.Lowell

The Green Dragon, Bishopsgate by T. Hosmer Shepherd, coloured by S.Lowell, 1856

The Bull Inn by T.Hosmer Shepherd, 1856

The Spread Eagle in Gracechurch St by R.B.Schnebblie, 1814

Sir Paul Pindar’s Lodge, Bishopsgate c. 1760

North East View of Bishopsgate Street, 1814

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Insititute

You may also like to take a look at

Will The Truman Brewery Become Homes Or Offices?

Messrs Truman, Hanbury, Buxton & Co’s Brewery, published by J. Moore 1842

Next week on 31st July, Tower Hamlets Council decides upon the future of the Truman Brewery and therefore on the future identity of Spitalfields itself.

The Truman Brewery was once the largest in the world. Reputedly founded in 1666, it expanded through the eighteenth and nineteenth century centuries, swallowing up the surrounding streets of houses to occupy an enormous site straddling Brick Lane. Even within living memory, there were eighteenth century houses lining the northern end of Wilkes St that were demolished for brewery expansion and the granite sets of this lost thoroughfare may still be seen traversing part of the former brewery site now known as Ely’s Yard.

After the Truman Brewery closed for good in 1989 and the site was unwanted, the Zeloof family bought it at an advantageous price and received public subsidy from the Council to refit the buildings as multiple work spaces. And it was this availability of cheap flexible spaces that provided the birthplace for the tech boom in London.

Today, the next generation of the Zeloof family want to monetise their inheritance by building new office blocks across the entire site and turning it into a corporate plaza, like Broadgate, Norton Folgate or Bishop’s Square. Yet this appalling proposal comes in the midst of London’s worst housing crisis and at a time when there is a surplus of office space in the capital.

There are more than 23,000 people on the Tower Hamlets housing list and a Community Masterplan commissioned by the Council estimates that the former brewery site could supply 345 homes for local people. In response, the Zeloofs are offering 6 social housing units in their development. The 7,500 letters of objection to the first Truman Brewery proposal were a clear indicator of public opinion on this issue.

For centuries, Brick Lane has served as the ‘Ellis Island’ of the United Kingdom where successive waves of migrants have arrived, enriching our culture and commerce by their presence. This is what has created the life of Spitalfields, characterised by its markets and independent small businesses. For descendants, it is a crucial location as the heartland of their cultural diaspora and, in this sense, the story of the place is the story of the creation of modern Britain. This is why people love Spitalfields.

We are at a watershed moment in our history now, in which the decision over the future of the Truman Brewery will define the nature of Brick Lane in perpetuity. The choice is clear. If the Zeloof family gets its way, their gated corporate plaza will push up property values and rents, driving out small businesses and offering homes only to the rich. But if the community’s wishes are respected, restoring streets of housing, offering small workspaces at affordable rents and opening up the closed thoroughfares, then this can ensure the survival of Spitalfields as a place to live and thrive.

Click here to sign the SAVE BRICK LANE petition

Click here to donate to the SAVE BRICK LANE fighting fund

Attend the Tower Hamlets Council Planning Committee meeting at the Town Hall in Whitechapel next Thursday 31st July at 6pm, either in person or online HERE

Office blocks will overshadow Allen Gardens

Luxury flats where Banglatown cash and carry stands today in Hanbury St

At Victoria Park Model Boat Club

January 3rd 1937

Keith Reynolds, a sympathetic man with an appealingly straggly moustache who is Secretary of the Victoria Model Steam Boat Club, agreed to let me take a look at his photographic collection. So, as the members got steam up on the lakeside, I sat inside the club house and sifted through the archive, listening to all the variously enigmatic whistling and chugging sounds coming from the shore.

Keith told me that the model boat club existed even before the founding of the Model Steam Boat Club in 1904, preceded by a Model Sailing Boat Club that he believes was founded in 1875. The old club house in Victoria Park dates from this period and Keith showed me where the lockers once were, custom-built to store huge model sail boats, before the age of steam took over.

There are just a handful of early black and white pictures, donated years ago by member Olive Cotman. Although the photograph at the top is from January 3rd 1937, the other one is undated. As well as the impressive display of boats in both photographs, the members display a fine selection of hats, and in the top picture, if you look closely, you can see the pennant-shaped club badge pinned onto many of the caps.

The dignity of these men, seemingly so serious in their moustaches and caps, yet so proud to be photographed with their fleet of model steam boats, is undeniably touching. These boats were miniature versions of the vessels that you might see a mile away on the Thames at that time.

By contrast, the 1937 picture shows the crowd who braved the chill wind of Victoria Park in January to admire the model boats and the anonymous schoolboy in his cap on the far right is more interested in the camera than the boats, as he gazes towards us and into eternity.

As I looked through the thousands of colour photographs taken by Janet Reynolds, Keith’s wife, over the forty summers since their marriage, I became fascinated by these idyllic pictures which evoke so many long happy Sunday afternoons. I was looking at images of the younger selves of those members of the club who I had been introduced to that morning. Keith has been sailing steam boats for fifty years, since he was ten, although he had to wait until he was fourteen to become a full-fledged member in his own right in 1964.

One day Keith’s father stopped by the lake to speak with the father of the current chairman Norman Lara, and that was how it began for the Reynolds family, which has now been involved for four generations. ‘She married into the Boating Club,’ admitted Keith affectionately, referring to the induction of his wife Jan, ‘She took photographs because she didn’t want to boat, but then she decided it was more fun to get involved, and now my daughter and my grandson of fourteen are also members.’ These lyrical images were taken by a photographer who became seduced by this diminutive nautical sport, embracing it as a family endeavour to entertain successive generations.

Out on the shore, Keith introduced me to the engineer Phil Abbott who showed me the oldest vessel still in use, a steam-powered straight-racing boat with the name of ‘All alone’ from 1920, beside it sat ‘Yvonne’ a high-speed steam-powered straight-racing boat from 1947. These boats speak of the different eras of their manufacture. ‘All alone,’ with its brass funnels and tones of brown with an eau-de-nil interior, possesses a quiet twenties elegance in direct contrast to the snazzy red and beige forties colour scheme of the speed boat which raises its prow arrogantly in the water as it roars along.

‘All alone’ was made by Arthur Perkins, who offered it to the club, as many members do, before his demise and ‘Yvonne’ has a similar provenance. When Keith revealed that he had acquired half of the thirty-seven boats he possessed, making the others himself, I realised that the club was the boats rather than the members, who are – in effect – mere custodians, providing maintenance for these vessels, enabling them to sail on, across Victoria Park Boating Lake, over decades and through generations.

Keith pinned a blue and white pennant-shaped enamel club badge on my shirt, just like those in the photo, and confessed that the club is eager for new members. It does not matter if you do not have a boat, anyone is welcome to join the conversation at the lakeside, and guidance is offered if you want to buy or make your own vessel, he explained courteously. All you need to do is go along to see Keith one Sunday in Victoria Park.

It would be the perfect excuse to spend every Sunday boating for the rest of your life and you would be joining the honoured ranks of men and women who have pursued this noble passtime since 1904 on the lake in Victoria Park. These treasured photographs speak for themselves.

You may also like to read about

Norman Phelps, Boat Club President

Lucinda Douglas Menzies at Victoria Park Steam Model Boat Club