The Bookshops Of Old London

At Marks & Co, 84 Charing Cross Rd

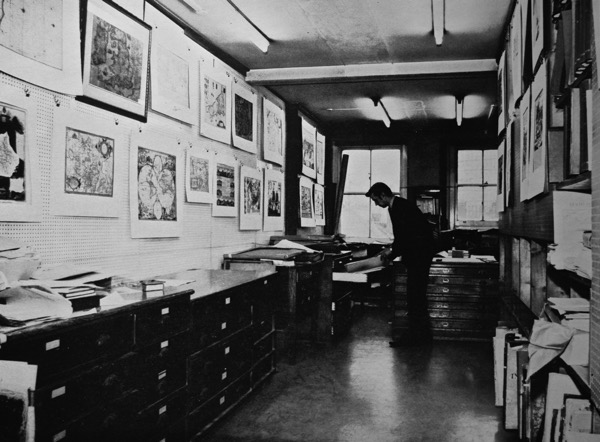

How I wish I could go back to the bookshops of old London. When I saw these evocative photographs of London’s secondhand bookshops taken in 1971 by Richard Brown, it made me realise how much I miss them all now that they have mostly vanished from the streets.

After I left college and came to London, I rented a small windowless room in a basement off the Portobello Rd and I spent a lot of time trudging the streets. I believed the city was mine and I used to plan my walks of exploration around the capital by visiting all the old bookshops. They were such havens of peace from the clamour of the streets that I wished I could retreat from the world and move into one, setting up a hidden bedroom to sleep between the shelves and read all day in secret.

Frustrated by my pitiful lack of income, it was not long before I began carrying boxes of my textbooks to bookshops in the Charing Cross Rd and swapping them for a few banknotes that would give me a night at the theatre or some other treat. I recall the wrench of guilt when I first sold books off my shelves but I found I was more than compensated by the joy of the experiences that were granted to me in exchange.

Inevitably, I soon began acquiring more books that I discovered in these shops and, on occasion, making deals that gave me a little cash and a single volume from the shelves in return for a box of my own books. In this way, I obtained some early Hogarth Press titles and a first edition of To The Lighthouse with a sticker in the back revealing that it had been bought new at Shakespeare & Co in Paris. How I would like to have been there in 1927 to make that purchase myself.

Once, I opened a two volume copy of Tristram Shandy and realised it was an eighteenth century edition rebound in nineteenth century bindings, which accounted for the low price of eighteen pounds. Yet even this sum was beyond my means at the time. So I took the pair of volumes and concealed them at the back of the shelf hidden behind the other books and vowed to return.

More than six months later, I earned an advance for a piece of writing and – to my delight when I came back – I discovered the books were still there where I had hidden them. No question about the price was raised at the desk and I have those eighteenth century volumes of Tristram Shandy with me today. Copies of a favourite book, rendered more precious by the way I obtained them and now a souvenir of those dusty old secondhand bookshops that were once my landmarks to navigate around the city.

Frank Hollings of Cloth Fair, established 1892

E. Joseph of Charing Cross Rd, established 1885

Mr Maggs of Maggs Brothers of Berkeley Sq, established 1855

Marks & Co of Charing Cross Rd, established 1904

Harold T. Storey of Cecil Court, established 1928

Henry Sotheran of Sackville St, established 1760

Andrew Block of Barter St, established 1911

Louis W. Bondy of Little Russell St, established 1946

H.M. Fletcher, Cecil Court

Harold Mortlake, Cecil Court

Francis Edwards of Marylebone High St, founded 1855

Stanley Smith of Marchmont St, established 1935

Suckling & Co of Cecil Court, established 1889

Images from The London Bookshop, published by the Private Libraries Association, 1971

You might also like to read about

The Spitalfields Bowl

One of these streets’ most-esteemed long-term residents summoned me to view an artefact that few have seen, the fabled Spitalfields Bowl. Engraved by Nicholas Anderson, a pupil of Laurence Whistler, it incarnates a certain moment of transition in the volatile history of this place.

I arrived at the old house and was escorted by the owner to an upper floor, and through several doors, to arrive in the room where the precious bowl is kept upon its own circular table that revolves with a smooth mechanism, thus avoiding any necessity to touch the glass. Of substantial design, it is a wide vessel upon a pedestal engraved with scenes that merge and combine in curious ways. You have the option of looking down upon the painstakingly-etched vignettes and keeping them separate them in your vision, or you can peer through, seeing one design behind the other, morphing and mutating in ambiguous space as the bowl rotates – like overlaid impressions of memory or the fleeting images of a dream.

Ever conscientious, the owner brought out the correspondence that lay behind the commission and execution of the design from Nicholas Anderson in 1988. Consolidating a day in which the glass engraver had been given a tour of Spitalfields, one letter lists images that might be included – “1. The church and steeple of Christ Church, Spitalfields, and its domination of the surrounding areas. 2. The stacks, chimneys and weaving lofts. 3. The narrowness of the streets and the list and lean of the buildings with their different doorways and casement windows.”

There is a mesmerising quality to Nicholas Anderson’s intricate design that plays upon your perception, offering insubstantial apparitions glimpsed in moonlight, simultaneously ephemeral and eternal, haunting the mind. You realise an object as perilously fragile as an engraved glass bowl makes an ideal device to commemorate a transitory moment.

“It took him months and months,” admitted the proud owner,“and it represents the moment everything changed in Spitalfields, in which the first skyscraper had gone up and there were cranes as evidence of others to come. The Jewish people have left and the Asians are arriving, while at the same time, you see the last of the three-hundred-year-old flower, fruit and vegetable market with its history and characters, surrounded by the derelict houses and filthy streets.”

Sequestered in a locked room, away from the human eye, the Spitalfields Bowl is a spell-binding receptacle of time and memory.

The Jewish soup kitchen

To the left is the Worrall House, situated in a hidden courtyard between Princelet St & Fournier St

A moonlit view of Christ Church over the rooftops of Fournier St

The bird cage with the canary from Dennis Severs House

“He was a tinker who overwintered in Allen Gardens and used to glean every morning in the market…”

To the left is Elder St and the plaque commemorating the birth of John Wesley’s mother is in Spital Sq.

An Asian couple walk up Brushfield St, with the market the left and the Fruit & Wool Exchange and Verdes to the right

Photographs copyright © Lucinda Douglas-Menzies

Tom Vowden, Stained Glass Conservator

One of my favourite places in the East End is Bow Church, so it was a delight to visit last week and meet Stained Glass Conservator, Tom Vowden, who is currently working on the east window. It made me feel less guilty about my own windows which get cleaned no more than once a year, when he told me that the east window is being cleaned for the first time since it was installed in the early fifties – more than sixty years ago.

Designed by H Lewis Curtis, this window dates from the early fifties, replacing one that was blown out when a bomb hit the church during the war. The window poses something of a mystery, since it has no religious iconography and is filled with a classical architectural structure within which images of small animals are discreetly placed.

Yet, in the lower part of the window, the blue coffered roof matches the Tudor ceiling in the chancel and, in the upper part of the window, the cupola reflects the design on the tower which was added when it was rebuilt at the same time the window was installed. H Lewis Curtis was the professional partner of architect Harry Goodhart Rendell who repaired Bow Church after the war.

A compelling suggestion to explain the presence of the animals in the window is that they honour Arthur Broome, former Rector of Bow and one of the founder members of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Animals that later became the RSPCA. At a meeting in June 1824, he was one of twenty-two people who gathered – possibly at Bow Church – to found a society that would protect animals from harm. It is even said that the debts incurred by the organisation in the early years meant that Broome himself was imprisoned.

Today the window forms a popular and intriguing puzzle for visitors who are invited to spot the owl, the butterfly, the pigeon, the cat, the mice and other creatures concealed in the design. And now that Tom has cleaned painstakingly the glass, this innocent pastime is even more attractive.

It was my privilege, as Tom’s guest, to climb up and take a much closer look at the window from the inside and the outside. So I took this opportunity to ask him about the profession of Stained Glass Conservator.

“I work on all kinds of glass from the medieval period until the modern day. Originally I studied archaeology and through that I got interested in historic crafts and the way things have been made throughout history. So I tried a few different things, I tried blacksmithing, glassblowing and marquetry before settling on stained glass. I found an apprenticeship at York Minster.

In my apprenticeship at the Minster, I worked on medieval glass but then I was at the Palace of Westminster for a couple of years working on nineteenth century glass. I replaced some of the glass on the face of Big Ben and we had to wait until the clock hands went past in order to fit the new pieces.

Making stained glass is a craft skill, but it is also artistic and you are playing with light. I am starting to design my own stained glass alongside my conservation work. Nowadays there’s less commissions for churches but more for front doors. Lead in stained glass has a lifespan of around a hundred years, and many houses in London are around that age, and it needs replacing.

The work I am doing at Bow Church is cleaning the surface of the glass and doing a couple of in situ repairs – there is a crack through one of the panes that needs resin bonding to weatherproof it. Mostly I am cleaning off the residue of pollution and sometimes there is a waxed layer in the interior where candles have been used. Pollution and pigeon droppings corrode the surface of glass over time and form a layer that allows condensation to settle which can cause any paint on the surface of the glass to deteriorate and be lost.

The east window that I am working on is not particularly old but it has an extreme amount of pollution for its age because of the location of this church with busy roads on either side. I find this window quite unusual because I cannot find a maker’s mark. It is one of the most interesting windows I have worked on. The design is unusual and it makes use of flashed glass, where glass is manufactured in two layers and the coloured layer is acid-etched through to the clear glass. Because it was manufactured in the fifties, this window is structurally sound but often with older windows are bowing which causes breaks.

Cleaning needs to be done fairly regularly to maintain the preserve the glass as well as possible. This is the first time this window has been cleaned since it was installed in the fifties. There’s not a huge amount of damage at this stage but if it was left for another hundred years or so it could get quite bad. Even something as simple as giving it a clean can really bring a window back to life. You see the texture in the glass that wouldn’t otherwise see.

In fifty years, I would be happy to come back and clean it again.”

Tom Vowden

Tom is cleaning the east window

Tudor roof in the chancel

Spot the owl

Spot the squirrel

Tom at work cleaning the exterior of the glass

The exterior of the east window

Repairs to the lead work on the roof is currently underway

The tower

The rear churchyard

You may also like to read about

Martin White, Textile Consultant

Today it is my pleasure to publish the story of Martin White, who has heroically reopened Crescent Trading, Spitalfields’ last cloth warehouse, after the death of his business partner Philip Pittack

Martin White, aged two in 1933

“That was the difference between Philip & me,” explained Martin White, articulating the precise distinction between himself and his business partner Philip Pittack, “He was a Rag Merchant, whereas I am a Textile Consultant. I understand textiles, I know about suitings and have been dealing in them since 1946. Our different specialities complemented each other.”

Famous for his monocle and pearl tiepin, as well as his unrivalled knowledge, Martin White was one half of the duo at Crescent Trading, possessing more than one hundred and twenty years of experience in the business between them. Their continuous comedy repartee won them a reputation as the Mike & Bernie Winters of the textile trade.

In particular, Martin is known for his ability to make an offer on a parcel of textiles on sight. “Very few people know how to do it,” he admitted to me. “Recently, Philip & I went on a buying trip twice a year, but in the past I used to go buying every day.” Martin’s story reveals how he acquired his remarkable knowledge of textiles, developing an expertise that permits him obtain the quality fabrics for which Crescent Trading is renowned.

“My father, William White, was a leather merchant but he also had some boot repair shops and, because he was a bit of mechanic, he rebuilt boot repairing machines. And that’s what he wanted me to go into. We lived in a very nice house in Shepherd’s Hill, Highgate, but unfortunately my father was diabetic who didn’t believe in conventional medicine. He was a herbalist and he became very ill in his forties and died at forty-six.

I started work at fourteen for my two uncles, Joe Barnet & Mark Bass (known as Johnny,) at their shop in Noel St off Berwick St in 1946. I was a little boy who didn’t know anything and in those days fabric was rationed and very hard to come by. Joe used to go up north and he had contacts in Manchester who used to get him stuff from the mills. It was a tiny shop and everything we got we sold immediately. They were making thousands every week and I was getting two pounds a week for carrying the fabric in and out. I used to like touching the fabric and that’s how I learnt about it.

While I was there, my father died and another of my uncles, David Bass, came to see my mother and he said he would take me to work for him and give me a wage, so she wouldn’t have to worry about me. But when the two uncles I was already working for heard this, Joe Barnet sent his wife Zelda to my mother to say that, if I worked for David, I would take all their customers from Noel St and it would ruin their business. So Joe Barnet told my mother he would look after me. He had just formed an association with a government supply business in Bethnal Green and he asked me to go down there and watch because he didn’t trust them, and that was my job.

So the first Friday came and he gave me five pounds, that was my wages. The following week, I found a parcel of cloth for sale in Brick Lane and I bought three thousand yards at a shilling a yard and I sold it for three shillings and sixpence a yard. The next Friday, Joe gave me fifteen pounds but I realised I had no chance of furthering myself with him, so I left and started working with another boy of my own age, Daniel Secunda. We were fifteen years old. We had no premises. We used to stand by the post at the corner of Berwick St, and people came to us with samples and goods to sell. We took the samples and sold them, and we made a good living between the two of us. We were young and we were carefree.All the money we earned, we spent it. We were happy. We went out every night. And that lasted for about three years, before the business got hard when rationing ended.

Then I met a guy who wanted to go into business properly with us, Pip Kingsley. He took premises in Berwick St and formed P. Kingsley & Co. After a while, it became apparent that while Danny was a very good-looking and likeable fellow, I was the worker out of the two of us. So Kingsley got rid of Danny and rehired an old job buyer who had retired, Myer King, and we started working together. He was an Eastern European, a very big man who couldn’t read or write. He had the knack of job buying ‘by the look.’ He’d go into a factory and make an offer for everything on the spot. This method of buying was different to anything I had ever seen but it worked. By working with him, I learnt what to do and what not do. And that knowledge was the basis of how I did business from then on.

I was happy working with Kingsley & Myer, but then I met my wife to be, Sheila, and I decided that I wanted my share of the money that my father had left in trust for my younger brother Adrian and me when we were twenty-one. I wanted to get married, and Sheila had been married before and she had a little boy. She was very beautiful. She’s eighty-five and she’s still beautiful.

My brother Adrian was known as Eddie and, at the age of eleven while my father was dying, he contracted sugar diabetes, so they were both in hospital. In the next bed to him was George Hackenschmidt, a boxer who had done body-building and my brother became interested in this. It was a very sad thing, my dad died when they were both in hospital and an uncle said to Eddie, ‘When you get out, I’ll buy you anything you want,’ to make him feel better. So Eddie said, ‘I want a set of weights.’

It was back in 1945, Eddie was twelve and he got one hundred pounds worth of weights and equipped a gym in our garage, and he started doing these workouts in the American magazines that George Hackenschmidt had given him. Eventually, he became Charles Atlas’ body. They would take the head of Charles Atlas and put it on a photo of my brother in the adverts for body-building.

When we broke my father’s trust fund, Eddie was twenty-one and we each received eight hundred pounds. My brother only lifted weights and sat in the sun, so I said to him, ‘What are you going to do with this? Give it to me and we’ll be partners, and I’ll do all the work and you can sit in the sun.’

Now, I wanted to get married to Sheila and her father was a textile merchant but her family didn’t like who I was. One of them was A. Kramer who happened to be Dave Bass’ solicitor and he phoned me up to warn me off her. So I told him what he could do, and Sheila and I got married in a registry office in 1955. Sheila’s little boy was four and her father, Lou Mason, didn’t want him to suffer, so he came to see me at my business and I showed him what I was buying.

Then he approached me one day and asked if I was interested in looking at a parcel of goods he had found in Wardour St at a lingerie company called Row G. So I went to see the parcel and made an offer of seven hundred pounds on sight. Lou said, ‘We don’t do business that way,’ and I said, ‘I’ll do it how I want to do it.’

The owner said, ‘No,’ but two weeks later I went back. He took the seven hundred pounds and it was all sold within two weeks for eighteen hundred pounds. My father-in-law said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s wonderful, why don’t you come and work with me?’ I couldn’t say, ‘No,’ to my father-in-law. There was no option. I said to my brother, ‘We’ll have to part company and I’ll give you your money back.’ He never forgave me.

The very first deal that came along was Cooper & Keyward, they had a lot of rolls of suiting and it came to two thousand pounds. But when I asked my father-in-law for the money to buy it, he said, ‘I’m a bit short this week.’ I just about had the two thousand pounds so I laid out the money myself and took the goods, and my father-in-law was able to sell it to his customers. On Friday, I said to him, ‘I need forty pounds to take my wife out,’ and he said, ‘We don’t spend money that way!’ So I fell out with my father-in-law. It turned out, he didn’t have the money to pay me because his business was going bankrupt.

I went round to get my goods which were in the basement of a shop in Berwick St and my mother-in-law was in the shop. A cousin came out and said, ‘You’re going to kill her, can’t we meet at the weekend and sort this out?’ At the meeting, my father-in-law accused me of being a liar but my wife’s aunt, Joyce, knew him and said to me, ‘I believe you.’ I never was a liar. She said to me, ‘If I lend you a thousand pounds, can you make a living?’

In Berwick St, Johnny Bass was trying to sell his stock at the shop where I had started work. The Noel St shop was full of fabric and he’d offered it to several people but no-one could assess what was there. He wanted four thousand pounds yet, because of my knowledge, I was able to cut a deal for two thousand four hundred pounds. It was Friday night and he said, ‘Give me some money.’ He’d just come of out of the bookmakers and he was penniless. I had a hundred pounds on me, so I gave him that and I had to find the rest of the money.

I went to get it from Joyce but she was in hospital. So I visited her and she said, ‘My husband Bert will get the money for you,’ and on the Monday he came with me to pay Johnny. Joyce had a property in Mansell St and I filled it up with the fabric and started selling it every day from there. Joyce was coming over to collect money from me in her handbag. She was charging me one hundred pounds a week rent plus interest, so I realised she thought I was working for her now but it wasn’t a partnership in my eyes and I wouldn’t go along with it.

I told her I wanted premises in Great Portland St and I needed money for that. It was agreed and that’s what we did. It was called the Robert Martin Company – Sheila’s son was called Robert. I got Daniel Secunda back to work with me. It was 1956, I had my own shop at last. And that’s how I became a textile merchant.”

Aged two, 1933

Aged three, 1934

Aged five in 1936

At school in Highgate, 1936

At a family wedding in September 1939. On the left are William & Muriel White, Martin’s parents. Beside them is Joe Barnet, Martin’s first employer, and his wife Zelda.

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin White & Danny Secunda, his first working partner in 1956

Martin White & Philip Pittack, Crescent Trading Winter 2010

Crescent Trading, Quaker Court, Quaker St, E1 6SN. Open Sunday-Friday.

You may also like to read about

The Return of Crescent Trading

The Re-Opening Of Crescent Trading

‘I want to sell my stock of textiles’

If you were eighty-nine years old and your business partner of thirty years died of Coronavirus, could you find the moral courage to go on? This is the brave step that cloth merchant Martin White has taken, re-opening Crescent Trading after the death of Philip Pittack. He and Philip were a charismatic double act, renowned for their ceaseless repartee and matchless knowledge of textiles. Last week, I went along to show my moral support, as the last cloth warehouse in Spitalfields reopened for business, and Martin confided his thoughts to me.

“On St Patrick Day, 17th March, I told Philip, ‘It’s too dangerous to be here and I am going home.’ I warned him, saying, ‘And you should as well.’ But ‘I’m not going,’ he said, ‘I’m not going…’

I called him every day from home and, the following week, he said ‘I’ve got take my wife to the hospital on Tuesday but have a good customer coming in, will you cover for me?’ I said, ‘No, I will not!’ I didn’t and I wouldn’t.

His wife’s visit to the hospital was nothing to do with the virus but she caught it and, all of a sudden, he began to feel unwell too. His daughter made him go to hospital, he was there for three weeks and they put him on a ventilator.

Philip had underlying health problems. For years, he had congestion of the lungs and diabetes. He also had several stents put in to deal with his heart problems and that fall didn’t do him any good. So he just couldn’t take the treatment for coronavirus. We all thought he was going to pull through but he didn’t, he died on 11th May.

Before we knew anything about the lockdown, Philip and I made an agreement about what to do with the business, whichever one of us went first. He was twelve years younger than me. I am eighty-nine and I was unwell for four months, so it left me in a strange and awkward position, which I have overcome. I have fulfilled all the conditions of our agreement.

Now I am working here on my own. I started coming in on Sundays and re-opened last week. I must admit I am delighted to be back. I love it, I love this work. I have been with Crescent Trading for thirty years but I have been in the trade since I was fourteen, that’s seventy-five years. I want to sell my stock of textiles.

Customers can only come in two at a time, they have to wear masks and use hand sanitiser. If they want to buy fabric, they can buy it. We are open for business.”

Martin White with his trademark monocle

Martin White & Philip Pittack in the old days

Crescent Trading, Quaker Court, Quaker St, E1 6SN. Open Sunday-Friday.

You may also like to read about

Philip Pittack & Martin White, Cloth Merchants

At The Halal Restaurant

The Halal Restaurant is open again and is part of the ‘Eat out to help out’ scheme

Just before midday at the Halal Restaurant, the East End’s oldest Indian restaurant, Mahaboob Narangali usually braces himself for the daily rush of curry hounds that have been filling his dining room every lunchtime since 1939. On the corner of Alie St and St Mark’s Place, occupying a house at the end of an eighteenth century terrace, the Halal Restaurant has plain canteen-style decor and an unpretentious menu, yet most importantly it has a distinctive personality that is warm and welcoming.

For the City workers coming here – nipping across the border into the East End – the Halal Restaurant is a place of retreat, and the long-serving staff are equally comfortable at this establishment that opens seven days a week for lunch and dinner. Stepping in by the modest side door of the Halal Restaurant, it is apparent that the small dining room to your right was the original front room of the old house while the larger room to your left is an extension added more recently. The atmosphere is domestic and peaceful, a haven from the nearby traffic thundering along Aldgate High St and down Leman St.

Even though midday was approaching, Mahaboob was happy to talk to me about his beloved restaurant and I was fascinated to listen, because I realised that what I was hearing was not simply the story of the Halal Restaurant but of the origin of all the curry restaurants for which the East End is celebrated today.

“Usman, my father, started working here in 1969. He came to Britain in the merchant navy and at first he worked in this restaurant, but then he became very friendly with the owner Mr Chandru and soon he was managing all three restaurants they had at that time. The other two were in Collum St in the City and in Ludgate Circus. Mr Chandru was the second owner, before that was Mr Jaffer who started the Halal Restaurant in 1939. Originally, this place was the mess of the hostel for Indian merchant seamen, with rooms up above. They cooked for themselves and then friends came round to eat, and it became a restaurant. At first it was just three kinds of curry – meat, meatball or mince curry. Then Vindaloos came along, that was more spicy – and now we sell more Vindaloos than any other dish. In the early nineties, Tandoori started to come in and that’s still popular.

My father worked hard and was very successful and, in 1981, he bought the restaurant from Mr Chandru. At twenty-one years old, I came to work here. It was just on and off at first because I was studying and my father didn’t want me to join the business, he wanted me to complete my studies and do something else, but I always had my eye on it. I thought, ‘Why should I work for someone else, when I could have this?’ And in 1988, I started running the restaurant. The leases of the other restaurants ran out, but we own the freehold here and I enjoy this work. I’ve only been here twenty-five years while many of our customers having been coming for forty years and one gentleman, Mr Maurice, he has been coming here since 1946! He told me he started coming here when was twelve.”

Intrigued to meet this curry enthusiast of so many years standing, I said my farewells to the Halal Restaurant and walked over from Aldgate to Stepney to find Mr Maurice Courtnell of the Mansell St Garage in Cannon St Row. I discovered him underneath a car and he was a little curious of my mission at first, but once I mentioned the name of the Halal Restaurant he grew eager to speak to me, describing himself proudly as “a true East Ender from Limehouse, born within the sound of Bow Bells.” A little shy to reveal his age by confirming that he had been going to the Halal Restaurant from the age of twelve, yet Maurice became unreservedly enthusiastic in his praise of this best-loved culinary insitution. “My father and my uncles, we all started going round there just after the Second World War.” he recalled with pleasure, “Without a doubt it is the best restaurant of any kind that I know – the place is A1, beautiful people and lovely food. I remember Mr Jaffer that started it, I remember holding Mahaboob in my arms when he was a new-born baby. Every Christmas we go round there for our Christmas party. It is the only restaurant I recommend, and I’ve fifteen restaurateurs as regular customers at my garage. When Leman St Police Station was open, all the police officers used to be in there. It is always always full.”

Held in the affections of East Enders and City Gents alike, the Halal Restaurant is an important landmark in our culinary history, still busy and still serving the same dishes to an enthusiastic clientele after more than eighty years. Of the renowned Halal Restaurant, it may truly be said, it is the daddy of all the curry restaurants in the East End.

Asab Miah, Head Chef at the Halal Restaurant, has been cooking for fifty years. Originally at the Clifton Restaurant in Brick Lane, he has been at the Halal Restaurant for the last twenty-seven years.

Quayum, Moshahid Ali, Ayas Miah, Mahadoob Narangoli, Asab Miah and Sayed.

At 12:01pm, the first City gent of the day arrives for curry at the Halal Restaurant.

Abdul Wahab, Mohammed Muayeed Khan and J.A. Masum.

At 12:02pm, the second City gent of the day arrives for curry at the Halal Restaurant.

Maurice Courtnell, owner of the Mansell St Garage and the Halal Restaurant’s biggest advocate. – “The place is A1, beautiful people and lovely food. I remember Mr Jaffer that started it, I remember holding Mahaboob in my arms when he was a new-born baby.”

Mahaboob Narangoli, owner of the East End’s oldest Indian restaurant.

In Old Rotherhithe

St Mary Rotherhithe Free School founded 1613

To be candid, there is not a lot left of old Rotherhithe – yet what remains is still powerfully evocative of the centuries of thriving maritime industry that once defined the identity of this place. Most visitors today arrive by train – as I did – through the Brunel tunnel built between 1825 and 1843, constructed when the growth of the docks brought thousands of tall ships to the Thames and the traffic made river crossing by water almost impossible.

Just fifty yards from Rotherhithe Station is a narrow door through which you can descend into the 1825 shaft via a makeshift staircase. You find yourself inside a huge round cavern, smoke-blackened as if the former lair of a fiery dragon. Incredibly, Marc Brunel built this cylinder of brick at ground level – fifty feet high and twenty-five feet in diameter – and waited while it sank into the damp earth, digging out the mud from the core as it descended, to create the shaft which then became the access point for excavating the tunnel beneath the river.

It was the world’s first underwater tunnel. At a moment of optimism in 1826, a banquet for a thousand investors was held at the bottom of the shaft and then, at a moment of cataclysm in 1828, the Thames surged up from beneath filling it with water – and Marc’s twenty-two-year-old son Isambard was fished out, unconscious, from the swirling torrent. Envisaging this diabolic calamity, I was happy to leave the subterranean depths of the Brunels’ fierce imaginative ambition – still murky with soot from the steam trains that once ran through – and return to the sunlight of the riverside.

Leaning out precariously upon the Thames’ bank is an ancient tavern known as The Spread Eagle until 1957, when it was rechristened The Mayflower – in reference to the Pilgrims who sailed from Rotherhithe to Southampton in 1620, on the first leg of their journey to New England. Facing it across the other side of Rotherhithe St towers John James’ St Mary’s Rotherhithe of 1716 where an attractive monument of 1625 to Captain Anthony Wood, retrieved from the previous church, sports a fine galleon in full sail that some would like to believe is The Mayflower itself – whose skipper, Captain Christopher Jones, is buried in the churchyard.

Also in the churchyard, sits the handsome tomb of Prince Lee Boo. A native of the Pacific Islands, he befriended Captain Wilson of Rotherhithe and his two sons who were shipwrecked upon the shores of Ulong in 1783. Abba Thule, the ruler of the Islands, was so delighted when the Europeans used their firearms to subdue his enemies and impressed with their joinery skills in constructing a new vessel, that he asked them to take his second son, Lee Boo, with them to London to become an Englishman.

Arriving in Portsmouth in July 1784, Lee Boo travelled with Captain Wilson to Rotherhithe where he lived as one of the family, until December when it was discovered he had smallpox – the disease which claimed the lives of more Londoners than any other at that time. At just twenty years old, Lee Boo was buried inside the Wilson family vault in Rotherhithe churchyard, but – before he died – he sent a plaintive message home to tell his father “that the Captain and Mother very kind.”

Across the churchyard from The Mayflower is Rotherhithe Free School, founded by two Peter Hills and Robert Bell in 1613 to educate the sons of seafarers. Still displaying a pair of weathered figures of schoolchildren, the attractive schoolhouse of 1797 was vacated in 1939 yet the school may still be found close by in Salter Rd. Thus, the pub, the church and the schoolhouse define the centre of the former village of Rotherhithe with a line of converted old warehouses extending upon the river frontage for a just couple of hundred yards in either direction beyond this enclave.

Take a short walk to the west and you will discover The Angel overlooking the ruins of King Edward III’s manor house but – if you are a hardy walker and choose to set out eastward along the river – you will need to exercise the full extent of your imagination to envisage the vast vanished complex of wharfs, quays and stores that once filled this entire peninsular.

At the entrance to the Rotherhithe road tunnel stands the Norwegian Church with its ship weather vane

Chimney of the Brunel Engine House seen from the garden on top of the tunnel’s access shaft

Isambard Kingdom Brunel presides upon his audacious work

Visitors gawp in the diabolic cavern of Brunel’s smoke-blackened shaft descending to the Thames tunnel

John James’ St Mary’s Rotherhithe of 1716

The tomb of Prince Lee Boo, a native of the Pelew or Pallas Islands ( the Republic of Belau), who died in Rotherhithe of smallpox in 1784 aged twenty

Graffiti upon the church tower

Monument in St Mary’s, retrieved from the earlier church

Charles Hay & Sons Ltd, Barge Builders since 1789

Peeking through the window into the costume store of Sands Films

Inside The Mayflower

A lone survivor of the warehouses that once lined the river bank

Looking east towards Rotherhithe from The Angel

The Angel

The ruins of King Edward III’s manor house

Bascule bridge

Nelson House

Metropolitan Asylum Board china from the Smallpox Hospital Ships once moored here

Looking across towards the Isle of Dogs from Surrey Docks Farm

Take a look at

Adam Dant’s Map of Stories from the History of Rotherhithe

and you may also like to read