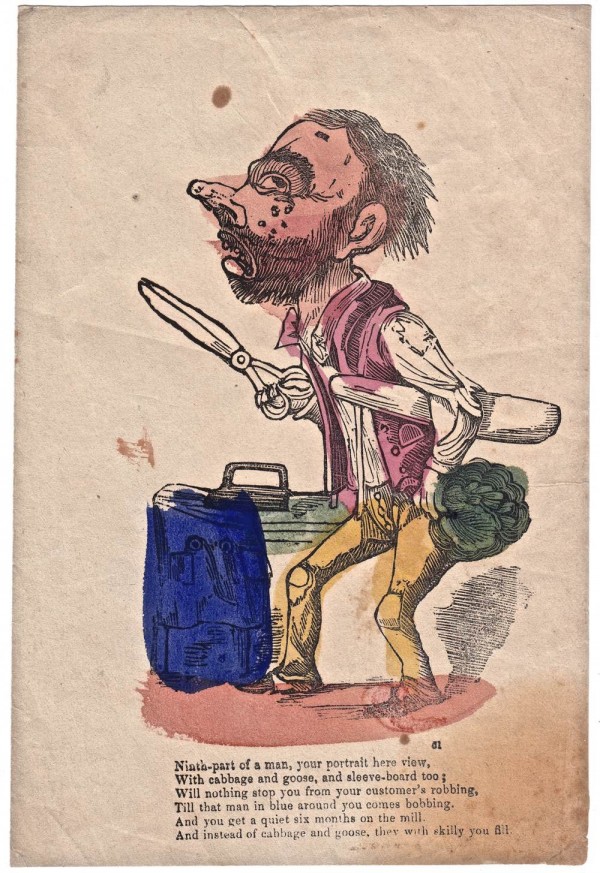

Vinegar Valentines

On Valentine’s Day when readers are contemplating billets-doux, perhaps some might like to consider reviving the Victorian culture of Vinegar Valentines?

When I met inveterate collector Mike Henbrey in the final months of his life, he showed me his cherished collection of these harshly-comic nineteenth century Valentines which he had been collecting for more than twenty years.

Mischievously exploiting the expectation of recipients on St Valentine’s Day, these grotesque insults couched in humorous style were sent to enemies and unwanted suitors, and to bad tradesmen by workmates and dissatisfied customers. Unsurprisingly, very few have survived which makes them incredibly rare and renders Mike’s collection all the more astonishing.

“I like them because they are nasty,” Mike admitted to me with a wicked grin, relishing the vigorous often surreal imagination manifest in this strange sub-culture of the Victorian age. Mike Henbrey’s collection of Vinegar Valentines were acquired by Bishopsgate Institute, where they are preserved in the archive as a tribute to one man’s unlikely obsession.

Images courtesy Mike Henbrey Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to look at

At The Custom House Public Inquiry

The Public Inquiry into the future of the Custom House has been running for two weeks now and today I publish this statement by Stepney resident and former-Director of the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery and the Royal Academy, Charles Saumarez Smith, which he delivered at the end of last week.

Custom House c. 1910 (Image courtesy LAMAS Collection, Bishopsgate Institute)

I have been following the battle which has been going on about the future development of the Custom House into – how did you guess ? – another luxury hotel.

Last week, I was allowed to give evidence to the Planning Inquiry which is currently taking place about the future of the Custom House. Most of the evidence is about the technicalities of planning law. I tried to address the broader issues of the protection of historic architecture as the City develops post-lockdown and what sort of City we want. Here is my submission.

CUSTOM HOUSE PLANNING INQUIRY, SUBMISSION OF THIRD-PARTY EVIDENCE BY SIR CHARLES SAUMAREZ SMITH

• I’m grateful for the opportunity to submit evidence to the Inquiry, having been encouraged to do so by the Gentle Author, whose daily blog, Spitalfields Life, has done such a good job in drawing attention to the amount of change and development which is currently going on in East London.

• I speak as someone who was trained as an architectural historian, writing a PhD. at the Warburg Institute on the architecture of Castle Howard, and who, since retiring from the Royal Academy of Arts as its Secretary and Chief Executive, has taken an increasing interest in issues of urban development. I live not so far away in East London, so have been watching what has been happening in the fringes of the City with increasing concern at its speed and its lack of regard for the history of the City.

• What I want to do is not so much discuss the merits and demerits — the detailed rights and wrongs — of the two proposals in front of you for the development of the Custom House. The first, from Cannon Capital Developments, is to turn the majority of the historic building into a commercial development, dominated, like the nearby Trinity House Building, by a big hotel: the scheme is, as described on the website, ‘hotel-led’. The second scheme, as put forward by the Georgian Group, is to ensure that there is proper public access to the building, particularly to the Long Room in the centre of the building, as has happened, for example, so successfully at Somerset House not far away, where you have such a successful combination of public and private use, opening up William Chambers’ central courtyard to public enjoyment; and, indeed, as has happened nearby at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, where its Great Hall is now vested in a separate trust, so is much more freely available to public use.

• Instead of looking at the detail of the two schemes, I would like to consider three broad contexts for understanding and looking at what is currently proposed.

• The first context is the way that access to the River Thames and the riverside more generally has been opened up to the public in the last twenty years: most obviously and most successfully in the stretch of the river from Tower Bridge to the Royal Festival Hall, where, for example, the conversion of the old industrial power station into Tate Modern has totally transformed that part of London for the better. We now take this development and its pleasures for granted, as if it has always been there, but I think it needs to be remembered that it was only Mark Fisher and the late Richard Rogers who effectively proposed opening up public access to the river in their book The New London, published in 1991, a proposal which then became public policy.[1]

• So far, the City has not in any way benefitted from a similar change, apart from the straggling Thames Path, which is currently the only way of actually seeing the Custom House — a building of vastly much greater historical interest and significance than Giles Gilbert Scott’s power station. Those of you who have tried walking the stretch of the Thames Path north of the river from Blackfriars Station to the Tower will have discovered that it is currently not a pleasant experience. It seems to me that, with a more imaginative and more publicly-oriented scheme which is devoted more than Cannon’s proposal currently is to opening up the Custom House to public access and public use, particularly on the river side, it might be possible to make a significant transformation to the public’s enjoyment of this part of the north side of the river, enabling people — not just tourists, not just guests at a luxury hotel, but city workers — to enjoy the riverbank west of the Tower of London.

• The last twenty years have seen London change from a city dominated by traffic into one where it is becoming easier to walk and explore; but not, I reiterate, in the part of the City round the Custom House. There is a great and historic opportunity to make the Custom House into a public amenity, not just another private hotel.

• The second context is a more obvious one, which is the history of the Custom House and its immense interest and importance as a historic building. Built immediately adjacent to the site of Christopher Wren’s Custom House, it represents that period of public architecture immediately after the Battle of Waterloo: a period of grand public buildings, including the National Gallery, University College and the British Museum, which was designed by Robert Smirke, who did the renovation of the Custom House in the 1820s. I am not going to pretend that David Laing, who designed the New Custom House in 1813, is an architect of equivalent interest and importance to Robert Smirke or William Wilkins. But, as you will all know, he was trained by Sir John Soane, the greatest architect of this period, and he designed the New Custom House in Soane’s style of very restrained and monumental classicism as first recorded by Sir Albert Richardson in his book Monumental Classic Architecture in Great Britain and Ireland, first published in 1914.[2]

• The third context I want to draw attention to and get you to think about is the world of work. Of course, none of us quite know what is going to happen in the future to the world of work. It is fairly obvious that the City is trying as hard as possible to ignore the fact that the pattern of work is changing, partly as a result of the last two years of the Coronavirus pandemic and lockdown, but not just because of lockdown. The City has carried on building huge great monolithic skyscrapers at incredible speed, particularly over the last two years, when we have seen 22, Bishopsgate absolutely dominate this part of the City. But the pattern of work is changing: becoming more casual, less 9 to 5, less insulated from the surrounding City, as much about meeting people as about sitting in front of a computer screen, perhaps a reversion to the world of the seventeenth-century coffee house.

• In early November, I visited Oslo, which has opened up its harbour area with the creation of three new public buildings: an opera house; a museum devoted to the work of Norway’s greatest artist, Edvard Munch; and a new public library. I visited the public library quite early in the morning. It was already absolutely full of people working on their laptops in small clusters. If you have visited the British Library recently, much of its activity is outside the reading rooms where the moment the Library opens, large numbers of workers occupy the public spaces, because people now need and want to work on their laptops in public spaces.

• So, having now considered these three broad contexts, I want to look back at what is currently proposed at the Custom House.

• On the one hand, you have plans for a commercial development by Cannon: as it is described on their website, the plan is for ‘a hotel-led scheme, with a museum, restaurants, cafes, meeting and event space and spa’. The plan is essentially for a hotel, equivalent perhaps to the Ned, close to the Bank of England, which in theory is publicly accessible for anyone willing to pay fifty pounds for lunch, but you are greeted by a man in uniform whose job it is to keep the broader public out.

• On the other hand, you have the proposals by the Georgian Group which are necessarily broader brush and less fully worked out in any detail, But the general underlying motive behind the Georgian Group’s proposals is abundantly clear: it is for mixed use — some offices in the east and west wing, but keeping the two great public spaces in the centre open for public access and public use, to be enjoyed by the citizens of this great capital city, as well as by tourists.

• I very much hope that the plans by Cannon will be turned down.

[1] Richard Rogers and Mark Fisher, The New London (London: Penguin Books, 1991).

[2] A.E. Richardson, Monumental Classic Architecture in Great Britain and Ireland (London: B.T. Batsford, 1914).

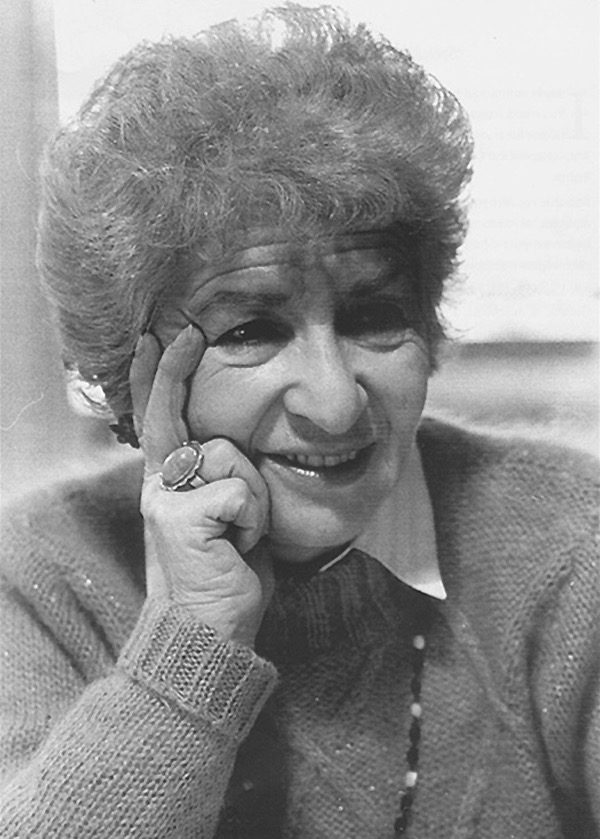

Charles Saumarez Smith © Rii Schroer

You may also like to read about

The Staircases Of Old London

Mercers’ Hall, c.1910

It gives me vertigo just to contemplate the staircases of old London – portrayed in these glass slides once used for magic lantern shows by the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society at the Bishopsgate Institute. Yet I cannot resist the foolish desire to climb every one to discover where it leads, scaling each creaking step and experiencing the sinister chill of the landing where the apparition materialises on moonless nights.

In the Mercers’ Hall and the Cutlers’ Hall, the half-light of a century ago glimmers at the top of the stairs eternally. Is someone standing there at the head of the staircase in the shadows? Did everyone that went up come down again? Or are they all still waiting at the top? These depopulated photographs are charged with the presence of those who ascended and descended through the centuries.

While it is tempting to follow on up, there is a certain grandeur to many of these staircases which presents an unspoken challenge – even a threat – to an interloper such as myself, inviting second thoughts. The question is, do you have the right? Not everybody enjoys the privilege of ascending the wide staircase of power to look down upon the rest of us. I suspect many of these places had a narrow stairway round the back, more suitable for the likes of you and I.

But since there is no-one around to stop us, why should we not walk right up the staircase to the top and take a look to see what is there? It cannot do any harm. You go first, I am right behind you.

Cutlers’ Hall, c.1920.

Buckingham Palace, Grand Staircase, c.1910.

4 Catherine Court, Shadwell c.1900.

St Paul’s Cathedral, Dean’s staircase, c.1920.

House of Lords, staircase and corridor, c.1920.

Fishmongers’ Hall, marble staircase, c.1920.

Girdlers’ Hall, c.1920.

Goldsmiths’ Hall, c.1920.

Merchant Taylors’ Hall, c.1920.

Cromwell House Hospital, Highgate Hill, c.1930.

Ironmongers’ Hall, c.1910.

Cromwell House Hospital, Highgate Hill, c.1930.

Stairs at Wapping, c.1910.

Cromwell House Hospital, Highgate Hill, c.1930.

Staircase at the Tower of London, Traitors’ Gate, c.1910.

Hogarth’s “Christ at the Pool of Bethesda” on the staircase at Bart’s Hospital, c.1910.

Lancaster House, c.1910.

2 Arlington St, c.1915.

73 Cheapside, c.1910.

Dowgate stairs, c.1910.

Crutched Friars, 1912.

Grocers’ Hall, c.1910.

Cromwell House Hospital, Highgate Hill, c.1930.

Salters’ Hall, Entrance Hall and Staircase, c.1910.

Holy Trinity Hospital, Greenwich, c.1910.

Salter’s Hall, c.1910.

Skinners’ Hall, c.1910.

1 Horse Guards Avenue, 1932.

Ashburnham House, Westminster, c.1910.

Buckingham Palace, c.1910.

Home House, Portman Sq, c.1910.

St Paul’s Cathedral, Dean’s Staircase, c.1920.

Glass slides courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Peter Bellerby, Globemaker

Just a couple of years ago, Peter Bellerby of Bellerby & Co was unable find a proper globe to buy his father for an eightieth birthday present. Now Peter is to be found in his very own globe factory in Stoke Newington and hatching plans to set up another in New York – to meet the growing international demand for globes which he expects to exceed ten times his current output within five years. A man with global ambitions, you might say.

Yet Peter is quietly spoken with deferential good manners and obviously commands great respect from his handful of employees, who also share his enthusiasm and delight in these strange metaphysical baubles which serve as pertinent reminders of our true insignificance in the grand scheme of things.

A concentrated hush prevailed as Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I ascended the old staircase in the former warehouse where we discovered the globemakers at work on the top floor, painstakingly glueing the long strips of paper in the shape of slices of orange peel (or gores as they are properly known) onto the the spheres and tinting them with fine paintbrushes to achieve an immaculate result.

“I get bored easily,” Peter confessed to me, revealing the true source of his compulsion, “But making globes is really the best job you can have, because you have to get into the zone and slow your mind down.”

“Back in the old days, they were incredibly good at making globes but that had been lost,” he continued, “I had nothing to go by.” Disappointed by the degradation of his chosen art over the last century, Peter revealed that, as globes became decorative features rather than functional objects, accuracy was lost – citing an example in which overlapping gores wiped out half of Iceland. “What’s the point of that?,” he queried rhetorically, rolling his eyes in weary disdain.

“People want something that will be with them for life,” he assured me, reaching out his arms around a huge globe as if he were going to embrace it but setting it spinning instead with a beautiful motion, that turned and turned seemingly of its own volition, thanks to the advanced technology of modern bearings.

Even more remarkable are his table-top globes which sit upon a ring with bearings set into it, these spin with a satisfying whirr that evokes the music of the spheres. Through successfully pursuing his unlikely inspiration, Peter Bellerby has established himself as the world leader in the manufacture of globes and brought a new industry to the East End serving a growing export market.

To demonstrate the strength of his plaster of paris casting – yet to my great alarm – Peter placed one on the floor and leapt upon it. Once I had peeled my fingers from my eyes and observed him, balancing there playfully, I thought, “This is a man that bestrides the globe.”

Isis Linguanotto, Globepainter

John Wright, Globemaker

Chloe Dalrymple, Globemaker

Peter Bellerby, on top of the globe

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

The Ruin At The Hairdresser

Nicholson & Griffin, Hairdresser & Barber

The reasons why people go the hairdresser are various and complex – but Jane Sidell, Inspector of Ancient Monuments, and I visited a salon in the City of London for a purpose quite beyond the usual.

There is a hairdresser in Gracechurch St at the entrance to Leadenhall Market that is like no other. It appears unremarkable until you step through the tiny salon with room only for one customer and descend the staircase to find yourself in an enormous basement lined with mirrors and chairs, where busy hairdressers tend their clients’ coiffure.

At the far corner of this chamber, there is a discreet glass door which leads to another space entirely. Upon first sight, there is undefined darkness on the other side of the door, as if it opened upon the infinite universe of space and time. At the centre, sits an ancient structure of stone and brick. You are standing at ground level of Roman London and purpose of the visit is to inspect this fragmentary ruin of the basilica and forum built here in the first century and uncovered in 1881.

Once the largest building in Europe north of the Alps, the structure originally extended as far west as Cornhill, as far north as Leadenhall St, as far east as Lime St and as far south as Lombard St. The basilica was the location of judicial and financial administration while the forum served as a public meeting place and market. With astonishing continuity, two millennia later, the Roman ruins lie beneath Leadenhall Market and the surrounding offices of today’s legal and financial industries.

In the dark vault beneath the salon, you confront a neatly-constructed piece of wall consisting of fifteen courses of locally-made square clay bricks sitting upon a footing of shaped sandstone. Clay bricks were commonly included to mark string courses, such as you may find in the Roman City wall but this usage as an architectural feature is unusual, suggesting it is a piece of design rather than mere utility.

Once upon a time, countless people walked from the forum into the basilica and noticed this layer of bricks at the base of the wall which eventually became so familiar as to be invisible. They did not expect anyone in future to gaze in awe at this fragment from the deep recess of the past, any more than we might imagine a random section of the city of our own time being scrutinised by those yet to come, when we have long departed and London has been erased.

Yet there will have been hairdressers in the Roman forum and this essential human requirement is unlikely ever to be redundant, which left me wondering if, in this instance, the continuum of history resides in the human activity in the salon as much as in the ruin beneath it.

You may also like to read about

Lorna Brunstein of Black Lion Yard

Lorna with her mother Esther in Whitechapel, 1950

In this photograph, Lorna Brunstein is held by her mother outside Fishberg’s jewellers on the corner of Black Lion Yard and Whitechapel Rd. It is a captivating image of maternal pride and affection that carries an astonishing story. The tale this tender photograph carries is one of how this might never have happened and yet, by the grace of fortune, it did.

I met Lorna upon her return visit to Whitechapel where she grew up the early fifties. Although she left Black Lion Yard at the age of six, it is a place that still carries great meaning for her even though it was demolished forty years ago.

We sat together in a crowded cafe in Whitechapel but, as Lorna told me her story, the sounds of the other diners faded out and I understood why she carries such affection for a place that no longer exists beyond the realm of memory.

“My relationship with the East End goes back to when I was born. I have scant memories, it was the early years of my childhood, but this was the area where I spent the first six years of my life. I was born in Mile End maternity hospital in December 1950.

Esther, my mother came to London in 1947. She was liberated from Belsen in April 1945 and she stayed in their makeshift hospital to recuperate for a few months. She had been through Auschwitz and lost all her family, apart from one brother who survived (though she did not know it at the time).

In the summer of 1945 she was taken to Sweden, to a place she said was beautiful – in the forest – where she and many others were looked after. It was while she was in Sweden that she and her brother Perec discovered via the Bund ( Polish Jewish workers Socialist party) that they had both survived. Esther was the youngest of three and Perec was the middle child. Their surname was Zylberberg, which means silver mountain. He was one of the boys who was taken to Windermere from Theresienstadt at the end of the War. They each wrote letters and confirmed that the other had survived. Esther had last seen Perec in March 1944.

After a few months in Windermere, he went to London and his sole mission was to get Esther over. That was all she wanted to do too, but it took two years from 1945 to 1947 for a visa to be granted. So not much has changed really. She was seventeen years old, had lost her mother at Auschwitz and her teenage years yet she was not allowed to come into the country unless she had a job, an address, and the name of a British citizen to be her guarantor and sponsor.

Maurice Regen (Uncle Moishe as I knew him) was an eccentric yet kind man. He came to London in the twenties from Lodz, which was my mother’s hometown. He and his wife were elderly, they had no children and lived in Romford. He said, ‘She can live in our house, so she will have an address, and she can be our housekeeper, that will be her job, and she won’t be dependent on the state.’ That was how my mother came over. My Uncle Perec met her and I think Uncle Moishe was probably there at Tilbury too.

She lived in Romford but she met Stan, my father, at the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre in Whitechapel where she was acting — her Yiddish was brilliant – and he was the scenic designer. He was an artist from Warsaw. He fled at the beginning of the War and was put in a labour camp in Siberia after spending fourteen months of solitary confinement in a prison in the Soviet Union. His story was pretty horrific too. He was an only child, and he lost everyone, his entire family. He was thirteen years older than my mother.

Stan also came to London in 1947. At the end of the War, he ended up in Italy. The Hitler/Stalin pact was broken while he was in Siberia and he was freed when the political amnesty was declared, so he joined up with the Polish Free Army under General Anders — as many of them did — and fought at the Battle of Monte Casino. Afterwards, he was in Rome for two years, studying scenic design at the Rome Academy of Fine Arts.

So my mother and father met in 1947 or 1948. I do not know exactly when. They got married in 1949 and I was born in 1950. They lived in a little flat in Black Lion Yard in Whitechapel until they moved to Ilford.

Rachel Fishberg – known as Ray – was really significant in my life and my parents’ life, my mother in particular. Ray was an old lady who became a surrogate grandma to my sister – who is four years younger – and me. We remember her with such affection. The Fishbergs were jewellers and were reasonably wealthy among Jewish people in the East End at that time. Ray ran her husband’s and his father’s jewellery shop, on the corner of Whitechapel Road and Black Lion Yard. I remember going back and visiting it when I was six, after we moved out.

My parents had no money, so grandma Ray Fishberg said they could live in the flat above the shop. At the time, they had nothing. My father could not live on his art and he took a diploma in design, tailoring and cutting at Sir John Cass School of Art in Aldgate. He designed and made children’s clothes on a sewing machine in the room we lived in and sold them in the market, and that was how we got by. Grandma Ray let them live there – probably for nothing – and, in fact, she paid for their wedding. When they got married in 1949 in Willesden Green, she paid for the wedding dress.

In 1957, when I was six, we moved to Ilford because my parents did not want to stay in the East End. She gave them the deposit for their first house. She was a lovely lady and she enabled them to have a start a life. This is why I feel so connected to this place, even though my memories of actually living here are scant.

I have this one memory of being in a pram, or maybe a pushchair, and feeling the sensation of the wheels on the cobbles in Black Lion Yard, going to the dairy — my mother said it was Evans the Dairy at the end of the Yard — to get milk.

Apparently, I went Montefiore School in Hanbury Street and I remember my mother talking about Toynbee Hall, where there were meetings, and taking me in the pram to Lyons Corner House in Aldgate where there was this chap, Shtencl, the poet of the East End.

He was quite an eccentric person who wandered around the streets and my mother told me he called into Lyons Corner House when she was sitting there with me as a baby. She said he stroked my head and said, ‘Sheyne, sheyne,’ which in Yiddish is ‘beautiful.’ My mother was in awe of him because his Yiddish was so brilliant and Yiddish was the language so dear to her heart. I was anointed by him even though I have no memory of him.

My mother and father talked a lot about Black Lion Yard. They said, on Sunday mornings at the entrance to Black Lion Yard where the pavement was quite deep, employers and potential employees in the tailoring ‘shmatte’ trade would gather and connect. That was what my father was doing then. He would stand there on a Sunday morning to get work.

Those were the founding years of my life. I have a deep affection for this place because for my parents – even though they wanted to leave for a better life – it was where they found sanctuary. My father used to say, ‘Thank goodness I’m here, I’ve finally found a place where I am able to walk down the street without having to look over my shoulder.”

Black Lion Yard, early seventies, by David Granick

Steps down to Black Lion Yard by Ron McCormick

Lorna aged eight

Esther & Stan Brunstein in the seventies

Esther Brunstein

Stan Brunstein

You may also like to read about

Luke Clennell’s London Melodies

I saw a raggedy man with crazy eyes disappear down Catherine Wheel Alley, so I followed to see what he was up to. When I entered the putrid alley, he disappeared around the corner, yet I heard him cry, “Rabbit, Rabbit. Nice Fat Rabbit!” So I hurried to catch up, and found myself lost in the maze of passages and back streets that fill the space between Bishopsgate and Middlesex St. Arriving at a cross-ways where several paths met, I could not see him anywhere. Uncertain which way to turn, I spotted a large woman swathed in layers of old clothes and wielding a heavy basket, trudging off down another alley with evident fatigue. Once she turned the corner, I followed her at a discreet distance and I could hear her shrill cry, “Lilies of the Valley, Sweet Lilies of the Valley,” echoing between the high walls. But again, when I turned the corner, she had vanished. Then, I heard another behind me, crying, “Hot Mutton Dumplings – Nice Dumplings, All Hot!” and so I retraced my steps.

Let me explain, I had just spent the morning in the Bishopsgate Institute poring over a small book of prints entitled, “London Melodies; or Cries of the Seasons.” Published anonymously and bound in non-descript brown boards, and printed on cheap paper with several torn pages – even so, the appreciative owner had inscribed it with his name and the date 1823 in a careful italic script.

This book entranced me with the vivid quality of its beautiful wood engravings of street hawkers. Commonly in the popular prints illustrating Cries of London, the peddlers are sentimentalised, portrayed with cheerful faces and rosy cheeks, ever jaunty as they ply their honest trades.

These lively wood engravings could not be more different. These people look filthy, with bad skin and teeth, dressed in ragged clothes, either skinny as cadavers or fat as thieves, and with hands as scrawny as rats’ claws. You can almost smell their bad breath and sweaty unwashed bodies, pushing themselves up against you in the crowd to make a hard sell. These Cries of London are never going to be illustrated on a tea caddy or tin of Yardley Talcum Powder and they do not give a toss. They are a rough bunch with ready fists, that you would not wish to encounter in a narrow byway on a dark night, yet they are survivors who know the lore of the streets and how to turn a shilling as easily as a groat. With unrivalled spirit, savage humour, profane vocabulary and a rapacious appetite, they are the most human of all the Cries of London I have come across. And they call to me across the centuries, crying, “Sweet and Pretty Beau-Pots – One a-Penny” and “Buy my Live Scate.”

Luke Clennell, Thomas Bewick’s most talented apprentice, is believed to be responsible for these superlative wood engravings, which capture the vigorous life of these loud characters with such art. From a contemporary perspective these portraits that sit naturally alongside the work of Ronald Searle, Ralph Steadman, Ian Pollock, Quentin Blake and Martin Honeysett. Clennell artist glories in the grotesque features and unrestrained personalities of street people, while also permitting them a humanity which we can recognise and respect. How I wish I could catch up with them all and record their stories for you.

Rabbit, Rabbit – Nice fat Rabbit

All Round & Sound, Full Weight, Threepence a Pound, my Ripe Kentish Cherries.

Buy my Fresh Herrings, Fresh Herrings, O! Three a Groat, Herrings, O!

Buy a Nice Wax Doll – Rosy and Fresh.

The King’s Speech, The King’s Speech to both Houses of Parliament.

Here’s all a Blowing, Alive and Growing – Choice Shrubs and Plants, Alive and Growing.

Hot Spice Gingerbread, Hot – Come buy my Spice Gingerbread, Smoaking Hot – Hot Spice Gingerbread, All Hot.

Any Earthen Ware, Plates, Dishes, or Jugs, today – any Clothes to Exchange, Madam?

Hot Mutton Dumplings – Nice Dumplings, All Hot.

Buy a Hat Box, Cap Box, or Bonnet Box.

Buy my Baskets, a Work, Fruit, or a Bread Basket.

Chickens, a Nice Fat Chicken – Chicken, or a Young Fowl.

Sweet and Pretty Beau-Pots, One a-Penny – Chickweed and Groundsel for your Birds.

Buy my Wooden Ware – a Bowl, Dish, Spoon or Platter.

Six Bunches a-Penny, Sweet Lavender – Six Bunches a-Penny, Sweet Blooming Lavender.

Here’s One a-Penny – Here’s Two a-Penny, Hot Cross Buns.

Lilies of the Valley, Sweet Lilies of the Valley.

Cats Meat, Dogs Meat – Any Cat’s or Dog’s Meat Today?

Buy my Live Scate, Live Scate – Buy my Dainty Fresh Salmon.

Mackerel, O! Four for shilling, Mackerel, O!

Hastings Green and Young Hastings. Here’s Young Peas, Tenpence a Peck, Marrow-fat Peas.

Images courtesy © Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders