Peter Bellerby, Globemaker

Just a couple of years ago, Peter Bellerby of Bellerby & Co was unable find a proper globe to buy his father for an eightieth birthday present. Now Peter is to be found in his very own globe factory in Stoke Newington and hatching plans to set up another in New York – to meet the growing international demand for globes which he expects to exceed ten times his current output within five years. A man with global ambitions, you might say.

Yet Peter is quietly spoken with deferential good manners and obviously commands great respect from his handful of employees, who also share his enthusiasm and delight in these strange metaphysical baubles which serve as pertinent reminders of our true insignificance in the grand scheme of things.

A concentrated hush prevailed as Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I ascended the old staircase in the former warehouse where we discovered the globemakers at work on the top floor, painstakingly glueing the long strips of paper in the shape of slices of orange peel (or gores as they are properly known) onto the the spheres and tinting them with fine paintbrushes to achieve an immaculate result.

“I get bored easily,” Peter confessed to me, revealing the true source of his compulsion, “But making globes is really the best job you can have, because you have to get into the zone and slow your mind down.”

“Back in the old days, they were incredibly good at making globes but that had been lost,” he continued, “I had nothing to go by.” Disappointed by the degradation of his chosen art over the last century, Peter revealed that, as globes became decorative features rather than functional objects, accuracy was lost – citing an example in which overlapping gores wiped out half of Iceland. “What’s the point of that?,” he queried rhetorically, rolling his eyes in weary disdain.

“People want something that will be with them for life,” he assured me, reaching out his arms around a huge globe as if he were going to embrace it but setting it spinning instead with a beautiful motion, that turned and turned seemingly of its own volition, thanks to the advanced technology of modern bearings.

Even more remarkable are his table-top globes which sit upon a ring with bearings set into it, these spin with a satisfying whirr that evokes the music of the spheres. Through successfully pursuing his unlikely inspiration, Peter Bellerby has established himself as the world leader in the manufacture of globes and brought a new industry to the East End serving a growing export market.

To demonstrate the strength of his plaster of paris casting – yet to my great alarm – Peter placed one on the floor and leapt upon it. Once I had peeled my fingers from my eyes and observed him, balancing there playfully, I thought, “This is a man that bestrides the globe.”

Isis Linguanotto, Globepainter

John Wright, Globemaker

Chloe Dalrymple, Globemaker

Peter Bellerby, on top of the globe

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

The Ruin At The Hairdresser

Nicholson & Griffin, Hairdresser & Barber

The reasons why people go the hairdresser are various and complex – but Jane Sidell, Inspector of Ancient Monuments, and I visited a salon in the City of London for a purpose quite beyond the usual.

There is a hairdresser in Gracechurch St at the entrance to Leadenhall Market that is like no other. It appears unremarkable until you step through the tiny salon with room only for one customer and descend the staircase to find yourself in an enormous basement lined with mirrors and chairs, where busy hairdressers tend their clients’ coiffure.

At the far corner of this chamber, there is a discreet glass door which leads to another space entirely. Upon first sight, there is undefined darkness on the other side of the door, as if it opened upon the infinite universe of space and time. At the centre, sits an ancient structure of stone and brick. You are standing at ground level of Roman London and purpose of the visit is to inspect this fragmentary ruin of the basilica and forum built here in the first century and uncovered in 1881.

Once the largest building in Europe north of the Alps, the structure originally extended as far west as Cornhill, as far north as Leadenhall St, as far east as Lime St and as far south as Lombard St. The basilica was the location of judicial and financial administration while the forum served as a public meeting place and market. With astonishing continuity, two millennia later, the Roman ruins lie beneath Leadenhall Market and the surrounding offices of today’s legal and financial industries.

In the dark vault beneath the salon, you confront a neatly-constructed piece of wall consisting of fifteen courses of locally-made square clay bricks sitting upon a footing of shaped sandstone. Clay bricks were commonly included to mark string courses, such as you may find in the Roman City wall but this usage as an architectural feature is unusual, suggesting it is a piece of design rather than mere utility.

Once upon a time, countless people walked from the forum into the basilica and noticed this layer of bricks at the base of the wall which eventually became so familiar as to be invisible. They did not expect anyone in future to gaze in awe at this fragment from the deep recess of the past, any more than we might imagine a random section of the city of our own time being scrutinised by those yet to come, when we have long departed and London has been erased.

Yet there will have been hairdressers in the Roman forum and this essential human requirement is unlikely ever to be redundant, which left me wondering if, in this instance, the continuum of history resides in the human activity in the salon as much as in the ruin beneath it.

You may also like to read about

Lorna Brunstein of Black Lion Yard

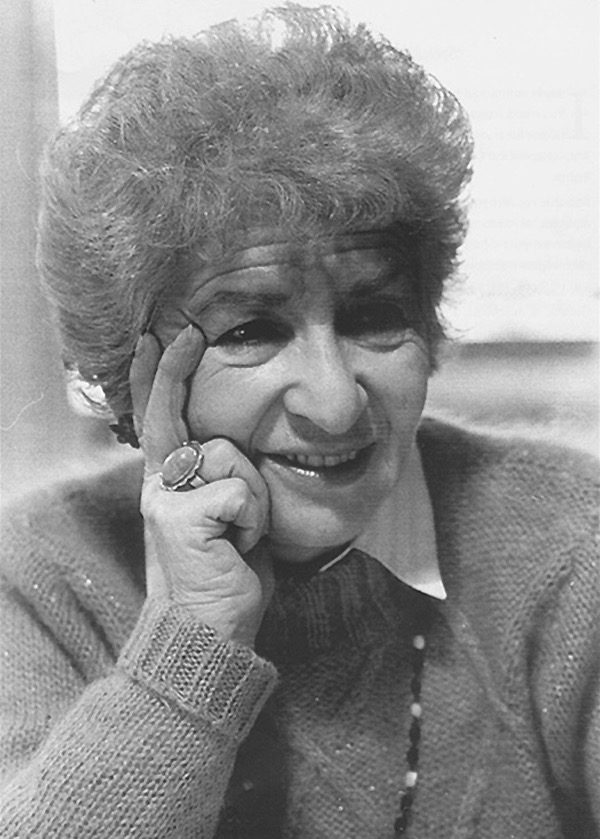

Lorna with her mother Esther in Whitechapel, 1950

In this photograph, Lorna Brunstein is held by her mother outside Fishberg’s jewellers on the corner of Black Lion Yard and Whitechapel Rd. It is a captivating image of maternal pride and affection that carries an astonishing story. The tale this tender photograph carries is one of how this might never have happened and yet, by the grace of fortune, it did.

I met Lorna upon her return visit to Whitechapel where she grew up the early fifties. Although she left Black Lion Yard at the age of six, it is a place that still carries great meaning for her even though it was demolished forty years ago.

We sat together in a crowded cafe in Whitechapel but, as Lorna told me her story, the sounds of the other diners faded out and I understood why she carries such affection for a place that no longer exists beyond the realm of memory.

“My relationship with the East End goes back to when I was born. I have scant memories, it was the early years of my childhood, but this was the area where I spent the first six years of my life. I was born in Mile End maternity hospital in December 1950.

Esther, my mother came to London in 1947. She was liberated from Belsen in April 1945 and she stayed in their makeshift hospital to recuperate for a few months. She had been through Auschwitz and lost all her family, apart from one brother who survived (though she did not know it at the time).

In the summer of 1945 she was taken to Sweden, to a place she said was beautiful – in the forest – where she and many others were looked after. It was while she was in Sweden that she and her brother Perec discovered via the Bund ( Polish Jewish workers Socialist party) that they had both survived. Esther was the youngest of three and Perec was the middle child. Their surname was Zylberberg, which means silver mountain. He was one of the boys who was taken to Windermere from Theresienstadt at the end of the War. They each wrote letters and confirmed that the other had survived. Esther had last seen Perec in March 1944.

After a few months in Windermere, he went to London and his sole mission was to get Esther over. That was all she wanted to do too, but it took two years from 1945 to 1947 for a visa to be granted. So not much has changed really. She was seventeen years old, had lost her mother at Auschwitz and her teenage years yet she was not allowed to come into the country unless she had a job, an address, and the name of a British citizen to be her guarantor and sponsor.

Maurice Regen (Uncle Moishe as I knew him) was an eccentric yet kind man. He came to London in the twenties from Lodz, which was my mother’s hometown. He and his wife were elderly, they had no children and lived in Romford. He said, ‘She can live in our house, so she will have an address, and she can be our housekeeper, that will be her job, and she won’t be dependent on the state.’ That was how my mother came over. My Uncle Perec met her and I think Uncle Moishe was probably there at Tilbury too.

She lived in Romford but she met Stan, my father, at the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre in Whitechapel where she was acting — her Yiddish was brilliant – and he was the scenic designer. He was an artist from Warsaw. He fled at the beginning of the War and was put in a labour camp in Siberia after spending fourteen months of solitary confinement in a prison in the Soviet Union. His story was pretty horrific too. He was an only child, and he lost everyone, his entire family. He was thirteen years older than my mother.

Stan also came to London in 1947. At the end of the War, he ended up in Italy. The Hitler/Stalin pact was broken while he was in Siberia and he was freed when the political amnesty was declared, so he joined up with the Polish Free Army under General Anders — as many of them did — and fought at the Battle of Monte Casino. Afterwards, he was in Rome for two years, studying scenic design at the Rome Academy of Fine Arts.

So my mother and father met in 1947 or 1948. I do not know exactly when. They got married in 1949 and I was born in 1950. They lived in a little flat in Black Lion Yard in Whitechapel until they moved to Ilford.

Rachel Fishberg – known as Ray – was really significant in my life and my parents’ life, my mother in particular. Ray was an old lady who became a surrogate grandma to my sister – who is four years younger – and me. We remember her with such affection. The Fishbergs were jewellers and were reasonably wealthy among Jewish people in the East End at that time. Ray ran her husband’s and his father’s jewellery shop, on the corner of Whitechapel Road and Black Lion Yard. I remember going back and visiting it when I was six, after we moved out.

My parents had no money, so grandma Ray Fishberg said they could live in the flat above the shop. At the time, they had nothing. My father could not live on his art and he took a diploma in design, tailoring and cutting at Sir John Cass School of Art in Aldgate. He designed and made children’s clothes on a sewing machine in the room we lived in and sold them in the market, and that was how we got by. Grandma Ray let them live there – probably for nothing – and, in fact, she paid for their wedding. When they got married in 1949 in Willesden Green, she paid for the wedding dress.

In 1957, when I was six, we moved to Ilford because my parents did not want to stay in the East End. She gave them the deposit for their first house. She was a lovely lady and she enabled them to have a start a life. This is why I feel so connected to this place, even though my memories of actually living here are scant.

I have this one memory of being in a pram, or maybe a pushchair, and feeling the sensation of the wheels on the cobbles in Black Lion Yard, going to the dairy — my mother said it was Evans the Dairy at the end of the Yard — to get milk.

Apparently, I went Montefiore School in Hanbury Street and I remember my mother talking about Toynbee Hall, where there were meetings, and taking me in the pram to Lyons Corner House in Aldgate where there was this chap, Shtencl, the poet of the East End.

He was quite an eccentric person who wandered around the streets and my mother told me he called into Lyons Corner House when she was sitting there with me as a baby. She said he stroked my head and said, ‘Sheyne, sheyne,’ which in Yiddish is ‘beautiful.’ My mother was in awe of him because his Yiddish was so brilliant and Yiddish was the language so dear to her heart. I was anointed by him even though I have no memory of him.

My mother and father talked a lot about Black Lion Yard. They said, on Sunday mornings at the entrance to Black Lion Yard where the pavement was quite deep, employers and potential employees in the tailoring ‘shmatte’ trade would gather and connect. That was what my father was doing then. He would stand there on a Sunday morning to get work.

Those were the founding years of my life. I have a deep affection for this place because for my parents – even though they wanted to leave for a better life – it was where they found sanctuary. My father used to say, ‘Thank goodness I’m here, I’ve finally found a place where I am able to walk down the street without having to look over my shoulder.”

Black Lion Yard, early seventies, by David Granick

Steps down to Black Lion Yard by Ron McCormick

Lorna aged eight

Esther & Stan Brunstein in the seventies

Esther Brunstein

Stan Brunstein

You may also like to read about

Luke Clennell’s London Melodies

I saw a raggedy man with crazy eyes disappear down Catherine Wheel Alley, so I followed to see what he was up to. When I entered the putrid alley, he disappeared around the corner, yet I heard him cry, “Rabbit, Rabbit. Nice Fat Rabbit!” So I hurried to catch up, and found myself lost in the maze of passages and back streets that fill the space between Bishopsgate and Middlesex St. Arriving at a cross-ways where several paths met, I could not see him anywhere. Uncertain which way to turn, I spotted a large woman swathed in layers of old clothes and wielding a heavy basket, trudging off down another alley with evident fatigue. Once she turned the corner, I followed her at a discreet distance and I could hear her shrill cry, “Lilies of the Valley, Sweet Lilies of the Valley,” echoing between the high walls. But again, when I turned the corner, she had vanished. Then, I heard another behind me, crying, “Hot Mutton Dumplings – Nice Dumplings, All Hot!” and so I retraced my steps.

Let me explain, I had just spent the morning in the Bishopsgate Institute poring over a small book of prints entitled, “London Melodies; or Cries of the Seasons.” Published anonymously and bound in non-descript brown boards, and printed on cheap paper with several torn pages – even so, the appreciative owner had inscribed it with his name and the date 1823 in a careful italic script.

This book entranced me with the vivid quality of its beautiful wood engravings of street hawkers. Commonly in the popular prints illustrating Cries of London, the peddlers are sentimentalised, portrayed with cheerful faces and rosy cheeks, ever jaunty as they ply their honest trades.

These lively wood engravings could not be more different. These people look filthy, with bad skin and teeth, dressed in ragged clothes, either skinny as cadavers or fat as thieves, and with hands as scrawny as rats’ claws. You can almost smell their bad breath and sweaty unwashed bodies, pushing themselves up against you in the crowd to make a hard sell. These Cries of London are never going to be illustrated on a tea caddy or tin of Yardley Talcum Powder and they do not give a toss. They are a rough bunch with ready fists, that you would not wish to encounter in a narrow byway on a dark night, yet they are survivors who know the lore of the streets and how to turn a shilling as easily as a groat. With unrivalled spirit, savage humour, profane vocabulary and a rapacious appetite, they are the most human of all the Cries of London I have come across. And they call to me across the centuries, crying, “Sweet and Pretty Beau-Pots – One a-Penny” and “Buy my Live Scate.”

Luke Clennell, Thomas Bewick’s most talented apprentice, is believed to be responsible for these superlative wood engravings, which capture the vigorous life of these loud characters with such art. From a contemporary perspective these portraits that sit naturally alongside the work of Ronald Searle, Ralph Steadman, Ian Pollock, Quentin Blake and Martin Honeysett. Clennell artist glories in the grotesque features and unrestrained personalities of street people, while also permitting them a humanity which we can recognise and respect. How I wish I could catch up with them all and record their stories for you.

Rabbit, Rabbit – Nice fat Rabbit

All Round & Sound, Full Weight, Threepence a Pound, my Ripe Kentish Cherries.

Buy my Fresh Herrings, Fresh Herrings, O! Three a Groat, Herrings, O!

Buy a Nice Wax Doll – Rosy and Fresh.

The King’s Speech, The King’s Speech to both Houses of Parliament.

Here’s all a Blowing, Alive and Growing – Choice Shrubs and Plants, Alive and Growing.

Hot Spice Gingerbread, Hot – Come buy my Spice Gingerbread, Smoaking Hot – Hot Spice Gingerbread, All Hot.

Any Earthen Ware, Plates, Dishes, or Jugs, today – any Clothes to Exchange, Madam?

Hot Mutton Dumplings – Nice Dumplings, All Hot.

Buy a Hat Box, Cap Box, or Bonnet Box.

Buy my Baskets, a Work, Fruit, or a Bread Basket.

Chickens, a Nice Fat Chicken – Chicken, or a Young Fowl.

Sweet and Pretty Beau-Pots, One a-Penny – Chickweed and Groundsel for your Birds.

Buy my Wooden Ware – a Bowl, Dish, Spoon or Platter.

Six Bunches a-Penny, Sweet Lavender – Six Bunches a-Penny, Sweet Blooming Lavender.

Here’s One a-Penny – Here’s Two a-Penny, Hot Cross Buns.

Lilies of the Valley, Sweet Lilies of the Valley.

Cats Meat, Dogs Meat – Any Cat’s or Dog’s Meat Today?

Buy my Live Scate, Live Scate – Buy my Dainty Fresh Salmon.

Mackerel, O! Four for shilling, Mackerel, O!

Hastings Green and Young Hastings. Here’s Young Peas, Tenpence a Peck, Marrow-fat Peas.

Images courtesy © Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

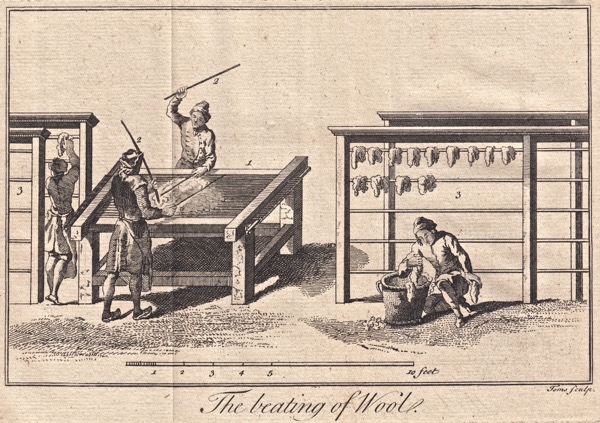

The Principal Operations of Weaving, 1748

Read my feature about Dennis Severs’ House with twelve pages of photographs by Antony Crolla in the March issue of World Of Interiors out now.

These copperplate engravings published below illustrate The Principal Operations of Weaving reproduced from a book of 1748 in the collection at Dennis Severs’ House. As you will discover, there was far more to weaving than sitting at a loom and many of these activities would have been a familiar sight in Spitalfields three centuries ago.

Ribbon Weaving

Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate House, Spitalfields, E1

Click here to book for DENNIS SEVERS’ TOUR devised by The Gentlle Author

You make also like to read about

Dennis Anthony’s Petticoat Lane

If you are looking to spruce up your linen cupboard with some fresh bolster cases or if it is time to replace those tired tea towels and soiled doilies, then these two lovely gentlemen are here to help. They have some super feather eiderdowns and quality blanket sets to keep you snug and cosy on frosty nights, and it is all going for a song.

One Summer Sunday in the nineteen fifties, Dennis Anthony took his camera down Petticoat Lane to capture the heroes of the epic drama of market life – all wearing their Sunday best, properly turned out, and even a little swanky. There is plenty of flash tailoring and some gorgeous florals to be admired in his elegant photographs, composed with dramatic play of light and shade, in compositions which appear simultaneously spontaneous and immaculately composed. Each of these pictures captures a dramatic moment – selling or buying or deliberating – yet they also reward second and third glances to scrutinise the bystanders and all the wonderful detail of knick-knacks gone long ago.

When the West End shops shut on Sundays, Petticoat Lane was the only place to go shopping and hordes of Londoners headed East, pouring through Middlesex St and the surrounding streets that comprised its seven “tributaries,” hungry for bargains and mad for novelty. How do I know this? Because it was the highlight of my parents’ honeymoon, when they visited around the same time as Dennis Henry, and I grew up hearing tales of the mythic Petticoat Lane market.

I wish I could buy a pair of those hob-nailed boots and that beret hung up beside the two sisters in shorts, looking askance. But more even than these, I want the shirt with images of records and Lonnie Donegan and his skiffle group, hung up on Jack’s stall in the final photograph. Satisfied with my purchases, I should go round to Necchi’s Cafe on the corner of Exchange Buildings and join those distinguished gentlemen for refreshment. Maybe, if I sat there long enough, I might even glimpse my young parents come past, newly wed and excited to be in London for the first time?

I am grateful to the enigmatic Dennis Anthony for taking me to Petticoat Lane in its heyday. I should like to congratulate him on his superlative photography, only I do not know who he is. Stefan Dickers, the archivist at the Bishopsgate Institute, bought the prints you see here on ebay and although they are labelled Dennis Anthony upon the reverse, we can find nothing more about the mysterious photographer. So if anyone can help us with information or if anyone knows where there are further pictures by Dennis Anthony – Stefan & I would be delighted to learn more.

You might also like to see

Laurie Allen of Petticoat Lane

The Wax Sellers of Wentworth St

Lewis Lupton In Spitalfields

In the spring of 1968, artist Lewis Frederick Lupton came to Spitalfields and submitted this illustrated report on his visit to the Christ Church Spitalfields Crypt Newsletter.

Interior of Christ Church, Spitalfields, 1968 – without galleries or floor

On Ash Wednesday 1968, I set off at eleven for Spitalfields to see the Rev. Dennis Downham about his work among alcoholic vagrants. Walking up the road from the Underground Station, I saw a man very poorly dressed, his face a pearly white, obviously ill. Then came a tramp, as lean, dirty, unkempt, bearded and ragged as any I have seen. This was a district where there was real poverty.

The Rectory was a substantial Georgian house such as one sees in many a country village. The study overlooked a small garden and the east end of the church, where plane trees grew among old tombstones.

After lunch, we went out to see something of the parish. The first person we encountered was a fine-looking young American in search of his ancestors, who asked for the parish registers. After directing him to County Hall, we crossed over into a narrow street between tall old brick houses with carved and moulded eighteenth century doorways. Out of one of these popped a little Jewish man with a white beard, black hat and coat.

Round the corner in Hanbury St, the Rector unlocked (“You have to be careful about locks here”) the door of a building in which the church now worships ( “Christ Church itself needs a lot spending in restoration before it can be used again”). The building now employed once belonged to a Huguenot church, of which there were seven in the parish, and still has the coat of arms granted by Elizabeth I carved above the communion table.

Thousands of French Protestants found a refuge from persecution in this parish. The large attic windows belonging to the rooms where they kept their looms may still be seen in many streets and the street names bear record of the exiles – Fournier St, Calvin St etc

Crossing Commercial St, we came across a charming seventeenth century shop in a good state of preservation. Its fresh paint made it stand out like a jewel from the surrounding drabness.

A stone’s throw further on, photographs pasted in a window advertised the attractions of one of the many night clubs in the area.

Opposite a kosher chicken shop, one of a the staff – a Jewish man with a beard, black hat and white coat was throwing pieces of bread to the pigeons.

Round the corner, we plunged into an offshoot of the famous Petticoat Lane which forms the western boundary of Spitalfields.

Turning eastwards, we tramped along the broken pavements of a narrow lane running through the heart of the district. It seemed to contain the undiluted essence of the parish in its fullest flavour, a mixture of food shops, warehouses, prison-like blocks of flats, derelict houses and bomb-sites. “There are twenty-five thousand people living in my parish. It is the only borough in central London which has residential life of its own,” revealed the Rector.

Christ Church stands out like a temple of light in the surrounding squalor. Designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, its scale is much larger than life and the newly-gilded weathervane is as high as the Monument. “I climbed up the ladders to the top last year when steeplejacks were at work upon it,” commented the Rector.

Christ Church stands out like a temple of light in the surrounding squalor. Designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, its scale is much larger than life and the newly-gilded weathervane is as high as the Monument. “I climbed up the ladders to the top last year when steeplejacks were at work upon it,” commented the Rector.

Were it not for the brave work which has been begun in the cellars, the building would only be a proud symbol of the Faith, no more.

Down the steps, to the left of the porch, there is a reception area with an office and a clothes store.

One sleeping fellow had a tough expression. “False nose,” said the Rector, “he had his real one bitten off in a fight.” The central area is devoted to the work for which the crypt was opened. Except for a billiard table, it is like a hospital ward, mainly taken up with beds on which the patients rest and sleep.

Yet, a crypt is crypt and the lack of daylight is a handicap but, with air-conditioning throughout, spotless cleanliness and a colour scheme of cream and turqoise blue, the cellars of Christ Church have been turned into a refuge which offers help and hope to those of the homeless alcoholics who have a desire to be rescued from their predicament. – L.F.L.

You may also like to read about