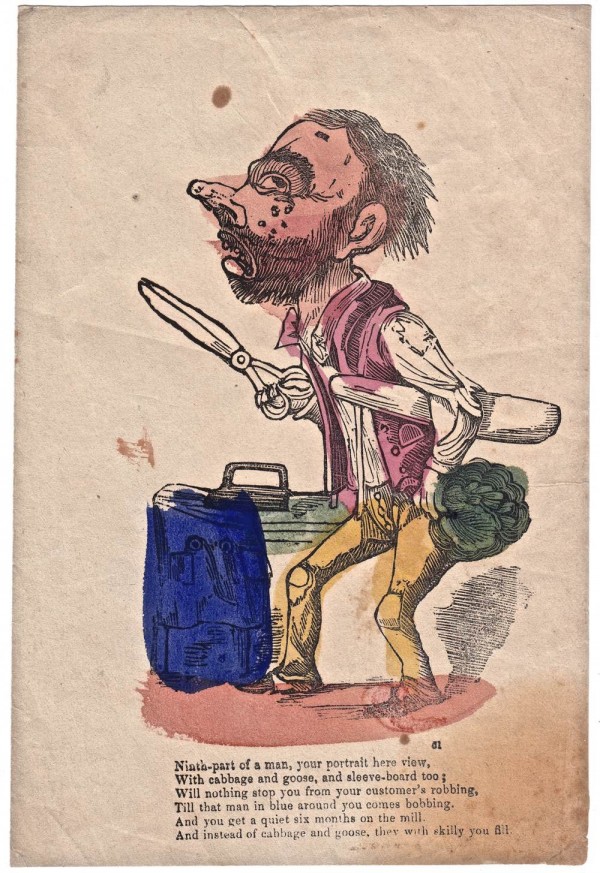

Mike Henbrey’s Vinegar Valentines

Inveterate collector, Mike Henbrey acquired harshly-comic nineteenth century Valentines for more than twenty years and his collection is now preserved in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

Mischievously exploiting the anticipation of recipients on St Valentine’s Day, these grotesque insults couched in humorous style were sent to enemies and unwanted suitors, and to bad tradesmen by workmates and dissatisfied customers. Unsurprisingly, very few have survived which makes them incredibly rare and renders Mike’s collection all the more astonishing.

“I like them because they are nasty,” Mike admitted to me with a wicked grin, relishing the vigorous often surreal imagination at work in his cherished collection – of which a small selection are published here today – revealing a strange sub-culture of the Victorian age.

Images courtesy Mike Henbrey Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to look at

Joyce Edwards’ Squatter Portraits

John the Fox, 1978

Half a century ago, documentary photographer Joyce Edwards (1925-2024) took these tender portraits of squatters who inhabited empty houses in the triangle of streets next to Victoria Park which had been vacated for the sake of a proposed inner city motorway that was never built. Her pictures are now being shown publicly for the first time at Four Corners in Bethnal Green in an exhibition entitled, Joyce Edwards: A Story Of Squatters, which opens tomorrow and runs until Saturday 20th March.

Joyce Edwards, 1980

Harold the Kangaroo, painter, with his dog Captain Beefheart, 1978

Billy Cowden, Joy Rigard & Jamie, 1978

Henry Woolf, actor, 1974

Beverly Spacie, 1977

Anthony & Andrew Minion, 1980

Elizabeth Shepherd, actor, c. 1970

John Peat, painter,1979

Gary Chamberlin, Beverly Spacie & Howard Dillon, 1977

Julia Clement, 1978

Vanessa Swann & Baz O’ Connell, 1979

Matthew Simmons, 1978

Shirley Robbins, 1977

Tosh Parker, 1977

Sue, 1977

Father & son, 1976

103 Bishops Way E2, Co-op headquarters, 1978

Attempted eviction, 1978

Joyce Edwards, 2012

Photographs copyright © Estate of Joyce Edwards

Joyce Edwards: A Story Of Squatters is at Four Corners, 121 Roman Rd, E2 0QN. Friday 13th February until Saturday 20th March (Wednesday to Saturday, 11am – 6pm)

You may also like to take a look at

Receipts From London’s Oldest Ironmonger

As any accountant will tell you – you must always keep your receipts. It was a dictum adopted religiously by the staff at London oldest ironmongers R. M. Presland & Sons in the Hackney Rd from 1797-2013, where this cache of receipts from the eighteen-eighties and nineties was discovered. They may no longer be of interest to the tax man, but they serve to illustrate the utilitarian beauty of nineteenth-century typographic design and tell us a lot about the diverse interrelated trades which once filled this particular corner of the East End.

You may also like to read about

In Search Of The Rope Makers Of Stepney

Rope makers of Stepney

In Stepney, there has always been an answer to the question, “How long is a piece of string?” It is as long as the distance between St Dunstan’s Church and Commercial Rd, which is the extent of the former Frost Brothers’ Rope Factory.

Let me explain how I came upon this arcane piece of knowledge. First I published a series of photographs from a copy of Frost Brothers’ Album in the archive of the Bishopsgate Institute produced around 1900, illustrating the process of rope making and yarn spinning. Then, a reader of Spitalfields Life walked into the Institute and donated a series of four group portraits of rope makers at Frost Brothers which I publish here.

I find these pictures even more interesting than the ones I first showed because, while the photos in the Album illustrate the work of the factory, in these newly-revealed photos the subject is the rope makers themselves.

There are two pairs of pictures. Photographed on the same day, the first pair taken – in my estimation – around 1900, show a gang of men looking rather proud of themselves. There is a clear hierarchy among them and, in the first photo, they brandish tankards suggesting some celebratory occasion. The men in bowler hats assume authority and allow themselves more swagger while those in caps withhold their emotions. Yet although all these men are deliberately presenting themselves to the camera, there is relaxed quality and swagger in these pictures which communicates a vivid sense of the personality and presence of the subjects.

The other two photographs show larger groups and I believe were taken as much as a decade earlier. I wonder if the tall man in the bowler hat with a moustache in the centre of the back row in the first of these is the same as the man in the bowler hat in the later photographs? In these earlier photographs, the subjects have been corralled for the camera and many regard us with a weary implacable gaze.

The last of the photographs is the most elaborately staged and detailed. It repays attention for the diverse variety of expressions among its subjects, ranging from blank incomprehension of some to the tenderness of the young couple with the young man’s hands upon the young woman’s shoulders – a fleeting gesture of tenderness recorded for eternity.

I was so fascinated by these photographs I wanted to go and find the rope works for myself and, on an old map, I discovered the ropery stretching from Commercial Rd to St Dunstan’s, but – alas – I could discern nothing on the ground to indicate it was ever there. The Commercial Rd end of the factory is now occupied by the Tower Hamlets Car Pound, while the long extent of the ropery has been replaced by a terrace of house called Lighterman’s Court that, in its length and extent, follows the pattern of the earlier building quite closely. At the northern end, there is now a park where the factory reached the road facing St Dunstan’s. Yet the terraces of nineteenth century housing in Bromley St and Belgrave St remain on either side and, in Bromley St, the British Prince where the rope makers once quenched their thirsts still stands.

After the disappointment of my quest to find the rope works, I cherish these photographs of the rope makers of Stepney even more as the best record we have of their existence.

Gang of rope makers at Frost Brothers (You can click to enlarge this image)

Rope makers with a bale of fibre and reels of twine (You can click to enlarge this image )

Rope makers including women and boys with coils of rope (You can click to enlarge this image)

Frost Brothers Ropery stretched from Commercial St to St Dunstan’s Churchyard in Stepney

In Bromley St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read the original post

Frost Bros, Rope Makers & Yarn Spinners

Founded by John James Frost in 1790, Frost Brothers Ltd of 340/342 Commercial Rd was managed by his grandson – also John James Frost – in 1905, when these photographs were taken. In 1926, the company was amalgamated to become part of British Ropes and now only this modest publication on the shelf in the Bishopsgate Institute bears testimony to the long-lost industry of rope making and yarn spinning in the East End, from which Cable St takes its name.

First Prize London Cart Parade – Manila Hemp as we receive it from the Philippines

Hand Dressing

The Old-Fashioned Method of Hand Spinning

The First Process in Spinning Manila – The women are shown feeding Hemp up to the spreading machines, taken from the bales as they come from the Philippines. These three machines are capable of manipulating one hundred and twenty bales a day.

Manila-Finishing Drawing Machines

Russian & Italian Hemp Preparing Room

Manila Spinning

Binder Twine & Trawl Twine Spinning – This floor contains one hundred and fifty six spindles

Russian & Italian Hemp Spinning

Carding Room

Tow Drawing Room

Tow Spinning & Spun Yarn Twisting Room

Tarred Yarn Store – This contains one hundred and fifty tons of Yarn

Tarred Yarn Winding Room

Upper End of Main Rope Ground – There are six ground four hundred yards long, capable of making eighteen tons of rope per ten and a half hour day

Rope-Making Machines – This pair of large machines are capable of making rope up to forty-eight centimetres in circumference

House Machines – This view shows part of the Upper Rope Ground and a couple of small Rope-Making Machines

Number 4 House Machine Room

The middle section of a machine capable of making rope from three inches up to seven inches in circumference, any length without a splice. It is thirty-two feet in height and driven by an electric motor.

Number 4 Rope Store

Boiler House

120 BHP. Sisson Engine Direct Coupled to Clarke-Chapman Dynamo

One of our Motors by Crompton 40 BHP – These Manila Ropes have been running eight years and are still in first class condition.

Engineers’ Shop with Smiths’ Shop adjoining

Carpenters’ Store & Store for Spare Gear

Exhibit at Earl’s Court Naval & Shipping Exhibition, 1905

View of the Factory before the Fire in 1860

View of the Factory as it is now in 1905 – extending from Commercial St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Henry Mayhew’s Street Traders

The Long-Song Seller

There is a silent ghost who accompanies me in my work, following me down the street and sitting discreetly in the corner while I am doing my interviews. He is always there in the back of my mind. He is Henry Mayhew, whose monumental work,”London Labour & London Poor,” was the first to give ordinary people the chance to speak in their own words. I often think of him, and the ambition and quality of his work inspires me. And I sometimes wonder what it was like for him, pursuing his own interviews, one hundred and fifty years ago, in a very different world.

Mayhew’s interviews and pen portraits appeared in the London Chronicle and were published in two volumes in 1851, eventually reaching their final form in five volumes published in 1865. In his preface, Mayhew described it as “the first attempt to publish the history of the people, from the lips of the people themselves – giving a literal description of their labour, their earnings, their trials and their sufferings in their own unvarnished language.”

These works were produced before photography was widely used to illustrate books, and although photographer Richard Beard produced a set of portraits to accompany Mayhew’s interviews, these were reproduced by engraving. Fortunately, since Beard’s photographs have not survived, the engravings were skillfully done. And they are fascinating images, because they exist as the bridge between the popular prints of the Cries of London that had been produced for centuries and the development of street photography, initiated by JohnThomson’s “Street Life in London” in 1876.

Primarily, Mayhew’s intention was to create a documentary record, educating his middle class readers about the lives of the poor to encourage social change. Yet his work transcends the tragic politics of want and deprivation that he set out to address, because the human qualities of his subjects come alive on the page and command our respect. Henry Mayhew bears witness not only to the suffering of poor people in nineteenth century London, but also to their endless resourcefulness and courage in carving out lives for themselves in such unpromising circumstances.

The Oyster Stall. “I’ve been twenty years and more, perhaps twenty-four, selling shellfish in the streets. I was a boot closer when I was young, but I had an attack of rheumatic fever, and lost the use of my hands for my trade. The streets hadn’t any great name, as far as I knew, then, but as I couldn’t work, it was just a choice between street selling and starving, so I didn’t prefer the last. It was reckoned degrading to go into the streets – but I couldn’t help that. I was astonished at my success when I first began, I made three pounds the first week I knew my trade. I was giddy and extravagant. I don’t clear three shillings a day now, I average fifteen shillings a week the year through. People can’t spend money in shellfish when they haven’t got any.”

The Irish Street-Seller. “I was brought over here, sir, when I was a girl, but my father and mother died two or three years after. I was in service, I saved a little money and got married. My husband’s a labourer, he’s out of worruk now, and I’m forced to thry and sill a few oranges to keep a bit of life in us, and my husband minds the children. Bad as I do, I can do a penny or tuppence a day better profit than him, poor man! For he’s tall and big, and people thinks, if he goes round with a few oranges, it’s just from idleniss.”

The Groundsel Man. “I sell chickweed and grunsell, and turfs for larks. That’s all I sell, unless it’s a few nettles that’s ordered. I believe they’re for tea, sir. I gets the chickweed at Chalk Farm. I pay nothing for it. I gets it out of the public fields. Every morning about seven I goes for it. I’ve been at business about eighteen year. I’m out till about five in the evening. I never stop to eat. I am walking ten hours every day – wet and dry. My leg and foot and all is quite dead. I goes with a stick.”

The Baked Potato Man. “Such a day as this, sir, when the fog’s like a cloud come down, people looks very shy at my taties. They’ve been more suspicious since the taty rot. I sell mostly to mechanics, I was a grocer’s porter myself before I was a baked taty. Gentlemen does grumble though, and they’ve said, “Is that all for tuppence?” Some customers is very pleasant with me, and says I’m a blessing. They’re women that’s not reckoned the best in the world, but they pays me. I’ve trusted them sometimes, and I am paid mostly. Money goes one can’t tell how, and ‘specially if you drinks a drop as I do sometimes. Foggy weather drives me to it, I’m so worritted – that is, now and then, you’ll mind, sir.”

The London Coffee Stall. “I was a mason’s labourer, a smith’s labourer, a plasterer’s labourer, or a bricklayer’s labourer. I was for six months without any employment. I did not know which way to keep my wife and child. Many said they wouldn’t do such a thing as keep a coffee stall, but I said I’d do anything to get a bit of bread honestly. Years ago, when I as a boy, I used to go out selling water-cresses, and apples, and oranges, and radishes with a barrow. I went to the tinman and paid him ten shillings and sixpence (the last of my savings, after I’d been four or five months out of work) for a can. I heard that an old man, who had been in the habit of standing at the entrance of one of the markets, had fell ill. So, what do I do, I goes and pops onto his pitch, and there I’ve done better than ever I did before.”

Coster Boy & Girl Tossing the Pieman. To toss the pieman was a favourite pastime with costermonger’s boys. If the pieman won the toss, he received a penny without giving a pie, if he lost he handed it over for nothing. “I’ve taken as much as two shillings and sixpence at tossing, which I shouldn’t have done otherwise. Very few people buy without tossing, and boys in particular. Gentlemen ‘out on the spree’ at the late public houses will frequently toss when they don’t want the pies, and when they win they will amuse themselves by throwing the pies at one another, or at me. Sometimes I have taken as much as half a crown and the people of whom I had the money has never eaten a pie.”

The Street- Seller of Nutmeg Graters. “Persons looks at me a good bit when I go into a strange place. I do feel it very much, that I haven’t the power to get my living or to do a thing for myself, but I never begged for nothing. I never thought those whom God had given the power to help themselves ought to help me. My trade is to sell brooms and brushes, and all kinds of cutlery and tinware. I learnt it myself. I was never brought up to nothing, because I couldn’t use my hands. Mother was a cook in a nobleman’s family when I was born. They say I was a love child. My mother used to allow so much a year for my schooling, and I can read and write pretty well. With a couple of pounds, I’d get a stock, and go into the country with a barrow, and buy old metal, and exchange tinware for old clothes, and with that, I’m almost sure I could make a decent living.”

The Crockery & Glass Wares Street-Seller. “A good tea service we generally give for a left-off suit of clothes, hat and boots. We give a sugar basin for an old coat, and a rummer for a pair of old Wellington boots. For a glass milk jug, I should expect a waistcoat and trowsers, and they must be tidy ones too. There is always a market for old boots, when there is not for old clothes. I can sell a pair of old boots going along the streets if I carry them in my hand. Old beaver hats and waistcoats are worth little or nothing. Old silk hats, however, there’s a tidy market for. There is one man who stands in Devonshire St, Bishopsgate waiting to buy the hats of us as we go into the market, and who purchases at least thirty a week. If I go out with a fifteen shilling basket of crockery, maybe after a tidy day’s work I shall come home with a shilling in my pocket and a bundle of old clothes, consisting of two or three old shirts, a coat or two, a suit of left-off livery, a woman’s gown maybe or a pair of old stays, a couple of pairs of Wellingtons, and waistcoat or so.”

The Blind Bootlace Seller. “At five years old, while my mother was still alive, I caught the small pox. I only wish vaccination had been in vogue then as it is now or I shouldn’t have lost my eyes. I didn’t lose both my eyeballs till about twenty years after that, though my sight was gone for all but the shadow of daylight and bright colours. I could tell the daylight and I could see the light of the moon but never the shape of it. I never could see a star. I got to think that a roving life was a fine pleasant one. I didn’t think the country was half so big and you couldn’t credit the pleasure I got in going about it. I grew pleaseder and pleaseder with the life. You see, I never had no pleasure, and it seemed to me like a whole new world, to be able to get victuals without doing anything. On my way to Romford, I met a blind man who took me in partnership with him, and larnt me my business complete – and that’s just about two or three and twenty year ago.”

The Street Rhubarb & Spice Seller. “I am one native of Mogadore in Morocco. I am an Arab. I left my countree when I was sixteen or eighteen years of age, I forget, sir. Dere everything sheap, not what dey are here in England. Like good many, I was young and foolish – like all dee rest of young people, I like to see foreign countries. The people were Mahomedans in Mogadore, but we were Jews, just like here, you see. In my countree the governemen treat de Jews very badly, take all deir money. I get here, I tink, in 1811 when de tree shilling pieces first come out. I go to de play house, I see never such tings as I see here before I come. When I was a little shild, I hear talk in Mogadore of de people of my country sell de rhubarb in de streets of London, and make plenty money by it. All de rhubarb sellers was Jews. Now dey all gone dead, and dere only four of us now in England. Two of us live in Mary Axe, anoder live in, what dey call dat – Spitalfield, and de oder in Petticoat Lane. De one wat live in Spitalfield is an old man, I dare say going on for seventy, and I am little better than seventy-three.”

The Street-Seller of Walking Sticks. “I’ve sold to all sorts of people, sir. I once had some very pretty sticks, very cheap, only tuppence a piece, and I sold a good many to boys. They bought them, I suppose, to look like men and daren’t carry them home, for once I saw a boy I’d sold a stick to, break it and throw it away just before he knocked at the door of a respectable house one Sunday evening. There’s only one stick man on the streets, as far as I know – and if there was another, I should be sure to know.”

The Street Comb Seller. “I used to mind my mother’s stall. She sold sweet snuff. I never had a father. Mother’s been dead these – well, I don’t know how long but it’s a long time. I’ve lived by myself ever since and kept myself and I have half a room with another young woman who lives by making little boxes. She’s no better off nor me. It’s my bed and the other sticks is her’n. We ‘gree well enough. No, I’ve never heard anything improper from young men. Boys has sometimes said when I’ve been selling sweets, “Don’t look so hard at ’em, or they’ll turn sour.” I never minded such nonsense. I has very few amusements. I goes once or twice a month, or so, to the gallery at the Victoria Theatre, for I live near. It’s beautiful there, O, it’s really grand. I don’t know what they call what’s played because I can’t read the bills. I’m a going to leave the streets. I have an aunt, a laundress, she taught me laundressing and I’m a good ironer. I’m not likely to get married and I don’t want to.”

The Grease-Removing Composition Sellers. “Here you have a composition to remove stains from silks, muslins, bombazeens, cords or tabarets of any kind or colour. It will never injure or fade the finest silk or satin, but restore it to its original colour. For grease on silks, rub the composition on dry, let it remain five minutes, then take a clothes brush and brush it off, and it will be found to have removed the stains. For grease in woollen cloths, spread the composition on the place with a piece of woollen cloth and cold water, when dry rub it off and it will remove the grease or stain. For pitch or tar, use hot water instead of cold, as that prevents the nap coming off the cloth. Here it is. Squares of grease removing composition, never known to fail, only a penny each.”

The Street Seller of Birds’ Nests. “I am a seller of birds’-nesties, snakes, slow-worms, adders, “effets” – lizards is their common name – hedgehogs (for killing black beetles), frogs (for the French – they eats ’em), and snails (for birds) – that’s all I sell in the Summertime. In the Winter, I get all kinds of of wild flowers and roots, primroses, buttercups and daisies, and snowdrops, and “backing” off trees (“backing,” it’s called, because it’s used to put at the back of nosegays, it’s got off yew trees, and is the green yew fern). The birds’ nests I get from a penny to threepence a piece for. I never have young birds, I can never sell ’em, you see the young things generally die of cramp before you can get rid of them. I gets most of my eggs from Witham and Chelmsford in Essex. I know more about them parts than anybody else, being used to go after moss for Mr Butler, of the herb shop in Covent Garden. I go out bird nesting three times a week. I’m away a day and two nights. I start between one or two in the morning and walk all night. Oftentimes, I wouldn’t take ’em if it wasn’t for the want of the victuals, it seems such a pity to disturb ’em after they made their little bits of places. Bats I never take myself – I can’t get over ’em. If I has an order of bats, I buys ’em off boys.”

The Street-Seller of Dogs. “There’s one advantage in my trade, we always has to do with the principals. There’s never a lady would let her favouritist maid choose her dog for her. Many of ’em, I know dotes on a nice spaniel. Yes, and I’ve known gentleman buy dogs for their misses. I might be sent on with them and if it was a two guinea dog or so, I was told never to give a hint of the price to the servant or anybody. I know why. It’s easy for a gentleman that wants to please a lady, and not to lay out any great matter of tin, to say that what had really cost him two guineas, cost him twenty.”

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

The Metropolitan Machinists’ Co, 1905

Last month – courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute – I published the 1896 cycling accessories catalogue of the Metropolitan Machinists’ Co of Bishopsgate Without and today I publish their catalogue from 1906 as an illustration of how rapidly cycling advanced into the new century, especially – as you will see – in the applied science of the ‘Anatomical Saddle’ which offered extra support to the ischial tuberosities.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Metropolitan Machinists’ Co, 1896