On The Beat With PC Lew Tassell

Lew Tassell at the Mansion House

Lew Tassell, formerly of the City of London Police, took me on a walk tracing the path of his old beat last week and regaled me with stories of his adventures in the City in the last century.

“I joined the City of London Police in June 1969. After thirteen weeks training at Eynsham Police Training Centre, I commenced divisional duties at Bishopsgate in September for about a month with an experienced officer and then on my own, patrolling for a two year probationary period.

The COLP had three divisions then – Bishopsgate, Wood St & Snow Hill. Each was split into areas, subdivided into beats. There were always plenty of officers patrolling and, although you were supposed to patrol alone, you very often teamed up with a colleague, as long as you were not caught by the Duty Inspector who patrolled for about an hour on each shift. If you saw the Inspector, you had to approach him, stand to attention, salute and state your beats. If you were “off your ground” or not on the area designated you could be in trouble.

In the days when there were few automated crossings, an officer would be posted to operate the lights manually and ensure smooth running of traffic during the rush hour. You could open the traffic light box with a key on your whistle chain to sequence the lights. At 8.00am and again at 18.00pm, there would always be two officers directing traffic at the junction of Aldgate, Minories and Houndsditch which was the busiest point. The entrances to Liverpool St Station would be manned during the rush hour to assist commuters. There were also two school crossing duties to cover in the morning and evenings, Dukes Place and Bishopsgate North by Pindar St, for the students at the Central Foundation School for Girls.

Between 7.00am and 20.00pm, three officers policed Tower Bridge. The rule was an officer for the North Tower, one for the South Tower and a third for the bascules, where it opens up. There were police boxes on both sides of the bridge for “inclement weather” but a four hour shift was quite boring, especially if it was quiet – so often we would often congregate in one box, keeping an eye out for an Inspector on patrol.

I also enjoyed being allocated bicycle duty on nights and at the weekends. You collected a standard sit-up-and-beg black bicycle and cycled anywhere on division for the whole shift that started and finished an hour earlier than usual to cover the change-over period. You wore standard uniform including your helmet and perhaps bicycle clips. I was knocked off my bike once as I was approaching Tower Bridge when a coach cut in, turning left into East Smithfield. Nothing was hurt apart from my pride as my helmet bounced down the street in front of onlookers.”

“I often took the short cut from Houndsditch through the Port of London Authority’s bonded warehouse in Cutler St to the back entrance of Bishopsgate Police Station in New St. The PLA policemen on the gates waved me through the complex which was built for the East India Company as their warehouse in the City and appeared to have changed little in 1969. It was dark and imposing, and I always felt the atmosphere of history. In one dark corner was the only facility permitted for the storage of opium. You could smell it from outside – or I assumed that was what it was. When the complex became derelict in the seventies, the City Police used it for firearms training.”

“I have enjoyed visiting the Lamb Tavern in Leadenhall Market frequently over fifty years. It is my favourite pub in London and thankfully has hardly changed. My introduction came on Christmas Eve 1969. Unlike today, most people in the City worked on Christmas Eve but everyone finished at midday and went to the pub. They got carried away and there were a lot of drunk people trying to make their way home in the afternoon when licensing hours meant the pubs had to stop serving at 3.30pm. Two officers were allocated to each pub to assist the landlord in clearing the bars. In 1969, I was allocated the Lamb. The atmosphere was generally good natured and there was little aggravation but there were a lot of drunk people, especially those that were once-a-year drinkers.

One Christmas Eve, I encountered a City gent in striped trousers and a bowler hat, with an umbrella, staggering towards me in Bishopsgate. He could not stand straight and hardly talk, but I managed to find out he had to catch a train from Broad St Station to somewhere in West London, so I literally carried him to the station and put him on a train home.”

“When I joined the Force I was taken out under instruction by an experienced officer. Most had places where they could stop for a cup of tea and a chat, it was a good way to meet the community. They were known as ‘tea holes.’ One of the ones I was taken to was a coffin factory, situated on the first floor of Artillery Lane at the junction with Sandys Row. It surprised me to find such an establishment in the City. All the carpenters made the coffins by hand with one floor entirely for storage. I was told that – by law -they had to keep at least two hundred coffins in case they should be required in an emergency, if there was a disaster.”

“Gun St is in Spitalfields and not strictly the City of London, but I would often cut through there from Brushfield St. There were a number of Victorian workshops, all run by the Asians, manufacturing clothing in sweatshops. In Gun St, they made leather coats and jackets and I purchased garments for myself, excellent quality and well made. The production process was astonishing to see, with dozens of people in a small space producing leather goods, measuring, cutting, stitching and sewing.”

“A favourite beat of mine was around and beneath Fenchurch St Railway Station, especially through French Ordinary Court. It was an alley that led into the underground cavernous area beneath the railway station arches. Cool in summer and warm in winter, there was an overwhelming smell of spices as you entered the tunnel. Sadly, they have managed to erase the spices but the cobbles are still there as you emerge into Crutched Friars, very close to another favourite spot – the churchyard of St Ghastly Grim.”

“The City of London Police Headquarters was situated at 26 Old Jewry since the Force was formed in 1839, it housed the offices of the Commissioner and Assistant Commissioner. The building was rebuilt in 1929 but, unusually for that time, retained the original staircase from 1725. Later, Old Jewry became the first offices of the Fraud Squad and the C.I.D. HQ. It was here I was interviewed to become a Cadet in 1967 and join the Force in 1969.”

“The City of London Magistrates Court opened in 1990 at 1 Queen Victoria St after the Mansion House and Guildhall Justice Rooms were closed.”

“Painted bright blue with an amber lamp on top, police boxes they were the main source of communication with officers on the beat before the advent of police radios. The general public could also summon help from a telephone in the upper part of the box. If an officer needed to be contacted, the amber light would flash on the boxes situated on his beat. If the light on the top was constantly illuminated, it signalled that royalty was in the City. By 1969, there were only a few occasions when you were not issued with a radio but, even so, the boxes were totally reliable unlike some of the radios.”

“I love rock music and going to gigs and, as a teenager, my favourite band were The Nice. They split in 1970 and keyboard player Keith Emerson formed Emerson Lake & Palmer with Greg Lake and Carl Palmer. In the spring of 1972, I noticed heavy boxes being unloaded from a large van in the lay-by outside the Fire Station in Bishopsgate with the word NICE painted on the sides. It could only be Keith Emerson’s equipment. The boxes were being taken into a lunchtime drinking club that was shut in the evenings called The Poor Millionaire, whose premises are now Dirty Martini. I had a chat to the roadies who invited me down and I spent the evening watching Emerson Lake & Palmer rehearsing their next album Trilogy. The band were very friendly and welcoming, and I got to play Keith’s Hammond organ while he was leaping around wearing my police helmet.”

“Officers in the City of London Police are given a silver statue of a policeman upon retirement if they complete thirty years’ service. The origin of this goes back to the thirties when Mrs Firminger Paton a director of Baston-Firminger Ltd, Commodity Brokers in Cullum St, used to drive to her offices in her Daimler from her home in Wimbledon every day. Police officers assisted her passage through the City and she was so impressed she invited them to her house and garden each year for beer and a buffet in a marquee. In return, the grateful officers made a collection and had a silver policeman made that could be screwed onto the bonnet of her Daimler. When Mrs Firminger Paton died in the seventies, the mascot was returned to the City Police and kept permanently in the Commissioner’s office at her request. So it was then decided that retiring officers should each receive a Silver Policeman of their own.”

Lew Tassell’s helmet

Lew Tassell’s oak truncheon which had been used by generations of policemen before him, dating back to the nineteenth century

Lew Tassell’s badge, keys and whistle

You may also like to take a look at

At Ben Truman’s House

Behold, the winter dusk is glimmering in this old house in Princelet St built in the seventeen-twenties for Benjamin Truman. A hundred years later, a huge factory was added on the back which more than doubled the size. In the twentieth century, this became the home of the extended Gernstein family from whom the current owners bought the house in the eighties. Notable as Lionel Bart’s childhood home, who once returned to have his portrait taken by Lord Snowden on the doorstep, in recent years it has served as the location for innumerable film and photo shoots. Then, as if to complete the circle, the house was sold to the proprietors of the Old Truman Brewery.

You may also like to take a look at

Joyce Ellis At Minto Place

Joyce Ellis

Billy Reading sent me this memoir by his great aunt Joyce Ellis, recalling her childhood visits to Minto Place, Bethnal Greet, home of her beloved grandfather James Ward (born 1861) and aunt Mary Ward (born 1888)

During the thirties, Mum and I used to visit my grandfather James Ward nearly every week in Bethnal Green, travelling by tram and bus from our home in Leyton. He lived at 5 Minto Place which was part of a terrace of houses whose front door opened straight onto the pavement. It was a rented house and the front upstairs bedroom was sub-let to Mr & Mrs Shave whom we never met.

Steep linoleum-clad stairs led directly up to grandfather’s tiny workroom at the back of the house. His trade was making hand-sewn ballet shoes, made from lovely soft leather, black, red and white, which when finished would dangle streamer-like on hooks from their long laces around the wall. He also made light-soled shoes and I can see him now, using hob and last, cutting, fixing the sole and hammering the tacks into place.

My grandfather sewed ballet shoes with waxed thread using two needles simultaneously which were curved at the ends, one held in each hand. He always wore a well-worn coarse apron, deeply marked with grease and dirt, and his hands bore the evidence of years of hard work. A fire burned in the grate in his work room in winter and it was stifling hot in summer, even when the sash window overlooking the yard and the adjoining grimy rooftops was thrown open wide. Frequently, he stopped for a rolled fag of good British Oak tobacco, which was lit by a homemade bullet-shaped lighter with a huge uncontrollable flame that had to be carefully manoeuvred to avoid singeing his moustache. And he supped large mugs of tea, in which he left the spoon whilst he drank.

Meanwhile, downstairs in the tiny scullery, Aunt Mary managed all the household duties in a quiet detached fashion. There was a coal-burning copper for clothes washing in one corner, with a deep sink and scrubbed wooden drainer attached, beside a small table and a cooker. Everything was spotlessly clean but very basic. When needed, odd slip mats were placed on the linoleum covered floor. Obviously, times were hard yet my Aunt was a wonderful manager, making the best of what was available.

Refreshments with my Aunt were taken in the dark front room. Bread, butter and jam, and quite often soda bread was provided, plus a good solid dripping cake with a handful of dried fruit. The fireplace had an over-mantle with ornaments and framed sepia photographs and, in winter, a coal fire flickered (excellent for making toast) and shone on the china cupboard with its coloured glass and decorated plates. The gas mantle over the fireplace was lit when dusk descended but not before in an effort to keep costs to a minimum. A fire would only be lit in a bedroom if the inhabitant was seriously ill – this was the only exception!

The scullery door led out into a small, walled backyard. It contained the lavatory with its scrubbed wooden seat and newspaper, carefully cut and hung on a string. The communal tap of the house was also in the yard alongside the tin bath hung from a nail on the wall. Jim, the terrier dog, had his kennel in the corner beside the mangle with large wooden rollers.

My grandfather had a disfiguring lump in his back. Apparently, he broke a bone years earlier while climbing a ladder at home but he scorned doctors and paid no attention to it at the time. In later years however, it gave forth an unpleasant discharge, although he never made any fuss about it. A very tough man, as those of his time and circumstances were, he had to survive and any show of weakness was scorned and belittled. His personal remedy for his ailment was ‘a good dose of liquorice powder,’ a tonic which he also administered to his dog.

Aunt Mary dutifully moved into Minto Place to care for my grandfather during his middle to later years. Missionary work in the East End of London was her life’s work and calling. Quite often accommodation went with the job and finally she became a caretaker and companion to a couple at a Jewish Mission close by Bethnal Green station. She always thought of the welfare of others with complete disregard for herself.

My grandfather was an Air Raid Warden during the Blitz and ruled Minto Place and its inhabitants with authority. His ‘local’ was the Lord Canrobert, just around the the corner in Canrobert St, to which made his way with clockwork regularity for a pint of beer. Cribbage was played and I seem to remember money being paid in weekly for various Thrift Clubs, a means of ensuring money was available, however little, when needed. Sometimes an unattended pram would be seen outside with a couple of young children in it, whilst the parents were imbibing, but mostly pubs were male-dominated while the women stayed at home.

Wolverly St playground and the dark satanic school with its high walls faced Minto Place. Neighbours often gathered at their hearthstone doorways, some sitting on chairs in sociable groups, for this was the place to exchange views or just watch life pass by. A cool breeze could be created by leaving the front and back doors wide open the filter air through the house. If you were lucky enough to scrounge an orange box from the market, add a set of old pram wheels, you were much sought after by companions. Home made scooters, were also popular, as well as hoops, tops and whips.

One method of washing was the Bag Wash. Clothes were boiled in vast coppers and taken home, after they had been mangled, to drape over what was available to dry, and irons were permanently kept by the fire to be heated when necessary.

This was the hey-day of the Pawn Broker with three brass balls hanging outside the shop. People in need of money urgently to pay off a debt, usually the rent, pledged whatever they thought might bring forward some ready cash – a suit of clothes, a watch perhaps – in the vain hope that they could pay back the Broker to redeem the items at a later date.

Most streets had a corner shop where such essentials as firewood at a penny a bundle could be bought. Paraffin and Carbolic Acid for drains were dispensed to your own tin or bottle, and Vinegar was stored in wooden casks – everything was sold loose. There were biscuits displayed in tins from which you made your own choice – pick ‘n’ mix – and broken biscuits were much sought after because they were cheaper. Household soap was sold as a long bar, cut to size as required, and stored for a while to harden in order to last longer.

Groups of musicians begged in the streets, frequently ex-service First World War veterans who were quite often limbless or blind and ever hopeful of a penny thrown their way. Unfortunately, most passersby were just as hard up themselves and could not afford to contribute.

East End Sunday mornings were never complete without a visit to crowded Petticoat Lane in Aldgate for shopping and meeting friends. The choice of goods and produce was vast, ranging from home made toffee and cough candies to fruit, flowers and vegetables. Herrings were sold straight out of deep barrels and live eels wriggled in trays until they came under the thud of the cleaver to be chopped into small pieces for the waiting customer. They did not come fresher than that! I shall leave the smell that pervaded the air to your imagination.

Hawkers sold bottles of medicine which they said would cure all your ailments. I well remember one who had the answer to the elimination of worms, which were quite prevalent in those days – I suppose through lack of general hygiene. He would have the offending worms on display, preserved in glass bottles, to support his claims. One had to be careful of bag-snatchers and pick-pockets in such crowds.

Nearby, Club Row was for the sale of livestock – puppies, barely old enough to leave their mothers, chicks to be reared in back yards for much-needed eggs, goldfish to be carried away triumphant in a jam jar. More or less anything could be bought or sold there.

Horse-drawn carts and wagons, both commercial and domestic – including the baker and the milkman – were still the main form of transport. While the carters were in pubs and cafes at lunchtime, horses were given their nosebags containing chaff, usually leaving great drifts of the stuff in the road where they had thrown up their heads to eat the reminder of the bag and spilt the contents. Great long stone drinking troughs were located at busy street corners for their consumption. Someone was always on the look out, ready to rush out armed with a bucket and shovel to sweep up the resultant manure for sale to the few who may have had a postage stamp-sized garden. I think the going rate was a penny a bucket.

My grandfather’s pride and joy was a very heavy bicycle on which he travelled everywhere, lit by a huge acetylene lamp. He had a black cape and sou’wester for wet days. When we lived in Leyton, Chingford and later Ilford, he regularly visited us on Sundays ‘on the bike’ up until his late seventies. His first encounter with a roundabout on the Woodford Avenue completely flummoxed him and he said he went round it the wrong way. Rene & I always received sixpence pocket money on these welcome visits. When we lived at 20 Flempton Rd, Leyton E10, my dad and grandad rented an allotment nearby. They shared the cost of seed, the work and the produce. Grandad cycled his share back to Bethnal Green in a hessian sack tied around his body. Dad built a nice shed with seats on three sides and hooks to keep the tools. A well was sunk and protected with a creosoted wooden lid.

Grandfather died in his mid-eighties after a short illness. Aunt Mary brought us the news – few people had telephones – and I can still remember the shock and emptiness that his death brought me. No more to hear the eagerly-awaited bell ring out on his bike to herald his arrival. No more to hear the latest news of Minto Place and its environs. He was a much-loved hardworking Victorian man, full of character and strength.

Minto Place was patched up many times after bomb attacks and was eventually pulled down for redevelopment. Aunt Mary was temporarily rehoused in a flat in the Guinness Buildings, Victoria Park, Bethnal Green, which was a dreadful depressing old building, long overdue for demolition. It was so dark that the light had permanently to be kept switched on. Lines of washing, secured from the balconies, stretched across courtyards until it was dry. Conversations seemed to echo from every level and the smell and feel of poverty was all around.

Thankfully, she was transferred to a block of flats know as Peabody Buildings in the Cambridge Heath Rd district of Bethnal Green, where she lived for a while, before finally moving as part of a London County Council scheme to relocate people out of London into the countryside at the edge of the Green Belt at Chigwell Row in Essex. It was retired person’s flat but it was not long before she found part-time work, helping the family with housekeeping. I hope they appreciated her fully and thought themselves fortunate to have her services, as there never was a more conscientious or hardworking person. She lived entirely for other people – Church, family and work were her priorities.

Aunt Mary visited us at Babbacombe Gardens, Ilford, once a month, travelling by bus to Gants Hill and changing. When my brother Martin was born in 1953, she took over from my mother at the time of his birth and stayed a couple of weeks to undertake all the household duties to the last detail.

Although she never had much money to spend, Aunt Mary had the magic touch with cookery and was always able to turn basic ingredients into an appetising meal. Her needlework was also born out of making something out of nothing. Invariably, second hand material was used and her stitches were so tiny they could hardly be seen.

BBC Radio Four was her constant companion, enabling her to keep abreast of current affairs, and reading widely was a great joy. The bible was the source of her knowledge, direction and peace of mind yet she was never sanctimonious or forced her faith upon us. Poetry was of particular interest to her and she would sometimes borrow my books to share and read aloud with her friends. I remember the Welsh poet W.H. Davies being one of her many favourites. Perhaps his early days as a tramp appealed to her?

Aunt Mary died aged seventy-six and is buried in Chigwell Row churchyard. Only upon reflection as an adult do I fully realise and appreciate her sterling, selfless qualities and sensitivity which endured unwaiveringly. I feel privileged to have such a dear aunt as my mentor.

James Ward enjoys a trip to the beach dressed in a three piece suit

A family group during the Second World War with James Ward second from right

You may also like to read

Henry Croft, Road Sweeper

Henry Croft

Trafalgar Sq is famous for the man perched high above it on the column, but I recently discovered another man hidden underneath the square who hardly anybody knows about and he is just as interesting to me. I have no doubt that if you were to climb up Nelson’s Column, the great Naval Commander standing on the top would have impressive stories to tell of Great Sea Battles and how he conquered the French, though – equally – if you descend into the crypt of St Martin in the Fields, the celebrated Road Sweeper who resides down there has his stories too.

Yet as one who was born in a workhouse and died in a workhouse, Henry Croft’s tales would be of another timbre to those of Horatio Nelson and some might say that the altitude history has placed between the man on the pedestal and the man in the cellar reflects this difference. Unfortunately, it is not possible to climb up Nelson’s Column to explore his side of this notion but it is a simple matter for anyone to step down into the crypt and visit Henry, so I hope you will take the opportunity when you next pass through Trafalgar Sq.

Henry Croft stands in the furthest, most obscure, corner far away from the busy cafeteria, the giftshop, the bookshop, the brass rubbing centre and the art gallery, and I expect he is grateful for the peace and quiet. Of diminutive stature at just five feet, he stands patiently with an implacable expression waiting for eternity, the way that you or I might wait for a bus. Yet in the grand scheme of things, he has not been waiting here long. Only since since 2002, when his life-size marble statue was removed to St Martin in the Fields from St Pancras Cemetery after being vandalised several times and whitewashed to conceal the damage.

Born in Somers Town Workhouse in 1861 and raised there after the death of his father who was a musician, it seems Henry inherited his parent’s showmanship, decorating his suit with pearl buttons while working as a Road Sweeper from the age of fifteen. Father of twelve children and painfully aware of the insecurities of life, Henry launched his own personal system of social welfare by drawing attention with his ostentatious outfit and collecting money for charities including Public Hospitals and Temperance Societies.

As self-appointed ‘Pearlie King of Somers Town,’ Henry sewed seven different pearly outfits for himself and many suits for others too, so that by 1911 there were twenty-eight Pearly King & Queens spread across all the Metropolitan Boroughs of London. It is claimed Henry was awarded in excess of two thousand medals for his charitable work and his funeral cortege in 1930 was over half a mile long with more than four hundred pearlies in attendance.

Henry Croft has passed into myth now, residing at the very heart of London in Trafalgar Sq beneath the streets that he once swept, all toshed up in his pearly best and awaiting your visit.

Henry Croft, celebrated Road Sweeper

At Henry Croft’s funeral in St Pancras Cemetery in 1930

You may also like to read about

David Hoffman At Fieldgate Mansions

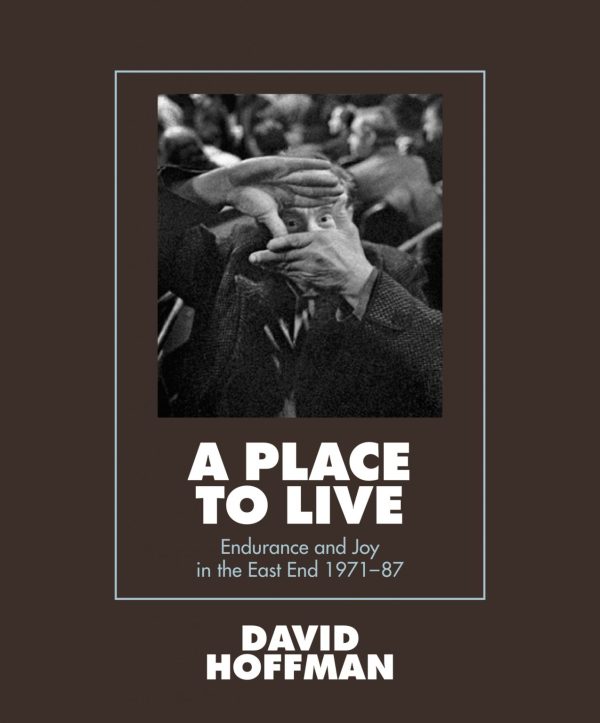

David Hoffman undertook a significant body of photography documenting the East End in the seventies and eighties that I plan to publish this year as a book entitled, A PLACE TO LIVE, Endurance & Joy in Whitechapel, accompanied by a major photographic exhibition at House of Annetta in Spitalfields.

I believe David’s work is such an important social document, distinguished by its generous humanity and aesthetic flair, that I must publish a collected volume. I already have a list of supporters for this project, so if you share my appreciation of David’s photography and might consider supporting this endeavour, please drop me a line at spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

Children playing at Fieldgate Mansions, April 1981

This series of photographs by David Hoffman, taken while he was squatting in Fieldgate Mansions off Fieldgate St in Whitechapel from 1973 until 1984, record a vital community of artists, homeless people and Bengali families who inhabited these streets at the time they were scheduled for demolition. Thanks to the tenacity and courage of these people, the dignified buildings survive today, restored and still in use for housing.

David Hoffman’s photographs record the drama of the life of his fellow squatters, subject to violent harassment and the constant threat of eviction, yet these images are counterpointed by his tender and intimate observation of children at play. After dropping out of university, David Hoffman found a haven in Fieldgate Mansion where he could develop his photography, which became his life’s work.

Characterised by an unflinching political insight, this photography is equally distinguished by a generous human sympathy and both these qualities are present in his Fieldgate Mansions pictures, manifesting the emergence of one photographer’s vision – as David Hoffman explained to me.

“It was the need for a place to live that brought me here. I’d come down from university without a degree in 1970. I’d dossed in Black Lion Yard and rented a squalid slum room in Chicksand St, before a permanent room came up for very little money in Black Lion Yard in 1971 above Solly Granatt’s jewellery shop. But the whole street was due for demolition, and when he died we squatted in it until they knocked it down in November 1973.

Then I found a place in Fieldgate Mansions which was being squatted by half a dozen people from the London College of Furniture. Bengali families were having a hard time and we were opening up flats in the Mansions for them to live there. We were really active, taking over other empty buildings that were being kept vacant in Myrdle St and Parfett St, because the owners found it was cheaper to keep them empty. We also squatted many empty houses further east in Stepney preventing the council from demolishing them. We took over and got evicted, and came back the next day and, when they put them up for auction, we used to bid and our bid won but, of course, we had no money so we couldn’t pay – it was a delaying tactic. It was a war of attrition to keep the buildings for people rather than for profit.

The bailiffs and police came at four in the morning and got everyone out and boarded up the property and put dogs in. Then we got dog handlers who removed the dogs and took them to Leman St Police Station as strays, and then we moved back in again.

When I moved into Fieldgate Manions it was late November and there was no hot water and the council had poured concrete down the toilet and ripped out the wiring. There was no insulation in the roof, it was just open to the slates and the temperature inside was as freezing as it was outside. I found a gas water heater in a skip and got it working on New Year’s Eve, so I counted in the New Year 1974 with hot water as the horns of the boats sounded on the river.

I decided to do Communication Design at the North East London Polytechnic, because I’d been taking photographs since I was a child and I’d helped set up a darkroom at university. At Fieldgate Mansions, I had a two room flat, one was my bedroom and office and other I made into a darkroom and I did quite a bit of photography. When I left college in 1976, I took up photography full time and began to make a slim living at it and I have done so ever since. While I was a student, I had a grant but I didn’t have to pay rent and it was the first time in my life I had enough money to feed and clothe myself. I stayed in Fieldgate Mansions until 1984 when I moved into a derelict house in Bow which I bought with some money I’d saved and what my mother left me, and where I still live today.”

Waiting to resist eviction in front of the barricaded front door of a squat in Myrdle St, Whitechapel, in February 1973. Ann Pettitt and Anne Zell are standing, with Duncan, Tony Mahoney and Phineas sitting in front.

Doris Lerner, activist and squatter, climbs through a first floor window of a squat in Myrdle St

Max Levitas, Tower Hamlets Communist Councillor, tried unsuccessfully to convince the squatters that resistance to eviction should be taken over by the Communist Party

March on Tower Hamlets Council in protest against the eviction of squatters

Doris Lerner in an argument with a neighbour during the evictions from Myrdle St and Parfett St

Lavatory in squatted house in Myrdle St, Whitechapel, 1973

Police arrive to evict squatters in Myrdle St

Eviction in progress

Out on the street

Sleeping on the street after eviction

Liz and Sue in my flat in Fieldgate Mansions, September 1975

Coral Prior, silversmith, working in her studio at Fieldgate Mansions, 1977

Fieldgate Scratch Band

A boy dances in the courtyard of Fieldgate Mansions. Scheduled for demolition in 1972, it was squatted to prevent destruction until taken over by a community housing trust and modernised in the eighties.

Photographs copyright © David Hoffman

You may also like to take a look at

David Hoffman at Crisis At Christmas

David Hoffman at Smithfield Market

At The Oldest Ceremony In The World

On these dark and frosty nights, I often think of the yeoman warders at the Tower of London pursuing their lonely vigils

Each night a lone figure in a long red coat walks down Water Lane, the narrow cobbled street enclosed between the mighty inner and outer walls of the Tower of London. Sometimes only his lamp can be seen through the thick river mist that engulfs him when it rises up from the Thames and pours over the wall to fill Water Lane, but he is indifferent to meteorological conditions because he is resolute in his grave task.

He is the Gentleman Porter and it is his responsibility to lock up the Tower, a duty fulfilled every single night since 1280, when the Byward Tower that houses the guardroom was built. And over seven centuries of repetition without remiss – day after day, down through the ages, through the Plague, the Fire and the Blitz – this time-hallowed ritual has acquired its own cherished protocol and tradition, becoming known as ‘The Ceremony of the Keys.” It is the oldest, longest running ceremony in the world, and it continues today and it will continue when we are gone.

John Keohane, the current Gentleman Porter ( a role also known since 1485 as the Yeoman Porter, and since 1914 by the title of Chief Yeoman Warder) invited me over to the Tower to watch the ceremony, and Spitalfields Life contributing photographer Martin Usborne was granted the rare privilege of taking pictures of a run-through for an event that at the request of the Sovereign has never been photographed.

“Welcome to my little house by the river,” declared John cheerily in greeting, “That’s what the Tower is, it’s my home.” There was a sharp breeze down by the Thames that night, and we were grateful to be led by John into the cosy octagonal vaulted guardroom in the Byward Tower which has been manned night and day since 1280 and has the ancient graffiti (Roger Tireel 1622, among others), the microwave and the video collection to prove it.

Here, John’s old friend Idwall Bellis, a genial Welshman, was preparing to spend a long night on duty. “People try to break in to the Tower of London all the time,” he confided with an absurd smile, explaining, “They climb into the moat and we contact the police to take them away. Occasionally, the Bloody Tower alarm goes off and no-one knows why, and sometimes foxes set off alarms too.” Like John, Idwall joined the Yeoman Warders in 1991 after a long army career and in the last twenty years he has seen it all, except one thing. “My predecessor Cedric Ramshall was here one night and the room filled with frost, he saw two men in doublets with long clay pipes standing at the fireplace and they pointed at him.” he revealed, gesturing to the spot in question, “He never spent another night in here again.”

At 9:53pm, it was time for John to light the huge old brass lantern, take up his bunch of keys and venture out into the glimmering dusk, mindful of the precise timing of the seven minute ceremony that must finish on the exact stroke of ten. The only time this did not happen, he informed me, was 29th December 1940 when a bomb fell within fifty feet and blew the warders off their feet. They picked themselves up, completed the ceremony and wrote a letter of apology to the King for being three minutes late – and he graciously replied to say he fully understood because of the enemy action taking place overhead.

Leaving the guardhouse, John walked alone with his lantern down Water St to the entrance to the Bloody Tower where he picked up an escort of Tower of London Guards uniformed in red with bearskins on their heads, who returned down Water Lane with him to the gates. “At the Middle Tower, I meet Mr Bellis and together we lock, close and secure the gates, while the soldiers offer us protection,” he explained to me with uncomplicated purpose. This prudent addition to the ritual was made in 1381 when an elderly Gentleman Porter was beaten up and left for dead by protesters against Richard II’s poll tax.

My heart leapt in my chest when, as the black doors closed upon the modern City with a thunderous bang, centuries ebbed away and I found myself suddenly isolated in the medieval world, in the sole company of soldiers in scarlet uniforms in a pool of lamplight in the ancient gatehouse – just as I might have done any time in the past seven hundred years. Once the huge doors were shut and barred, while a pair of guards stood on either side and a shorter one held up the lamp as John turned the key in the lock with a satisfying clunk, then the escort reformed and marched swiftly together back down Water Lane into the gathering darkness, with John Keohane at the head, leaving Idwall Bellis to return to his cosy guard room.

Keeping discreetly to the shadows, I followed down Water Lane, creeping along beneath the vast stone walls towering over me. It was at this moment that a sentry stepped from the shadows – in the dramatic coup of the evening – challenging those approaching out of the dusk, crying, “Halt! Who comes there?” With barely concealed affront, John halted his escort, announcing, “The keys!” And in a bizarre moment, centuries of repetition was rendered into the present tense, happening for the first time – as those involved embraced the irresistible drama of the instant and the loaded gun pointed at them.

“Who’s keys?” persisted the sentry – turning either dimwitted or subordinate. “Queen Elizabeth’s keys,” announced John, citing the Sovereign who is his direct employer. “Pass Queen Elizabeth’s keys, for all is well!” responded the sentry, a stooge stepping back into the shadow.

And then John, accompanied by his escort, marched triumphantly up into the precinct of the Tower where he met a contingent of guardsmen, waiting sentinel at the head of the stone steps. They presented arms and the clock started to chime, permitting eleven seconds before the stroke of ten. In a moment of brief exultation, spontaneous even after twenty years, John took two paces forward, raising his Tudor bonnet, and declaiming, “God Preserve Queen Elizabeth!” Finally, a bugler played the last post and the clock struck ten as he made his way up the steps to report to the Constable that the Tower was locked for the night.

The guard marched away to their barracks and I stood alone beneath the vast white tower, luminous with floodlight, and I cast my eyes around Tower Green that was my sole preserve in that moment. Then John returned, descending the staircase, and we walked down to the Bloody Tower where the young princes were murdered by their uncle Richard III and where Walter Raleigh was imprisoned for thirteen years. And before John Keohane and I shook hands and said our “Good Nights,” we lingered there for a moment in silent awe at the horror and the beauty of the place.

Idwall Bellis sits all night in the guard house waiting for people to break into the Tower of London.

The keys to the Tower of London and the lantern.

“Halt, who comes there?”

“The Keys!”

“God preserve Queen Elizabeth!”

Photographs copyright © Martin Usborne

You may also like to read about

John Keohane, Chief Yeoman Warder at the Tower of London

The Ceremony of the Lilies & Roses at the Tower of London

Constables Dues at the Tower of London

The Bloody Romance of the Tower

You can apply to attend the Ceremony of the Keys through Historic Royal Palaces. A limited number of guests are permitted each night and it is free. Please apply at least six weeks in advance and be sure to include several alternative dates in your application which must be accompanied by a stamped addressed envelope.

Residents of Spitalfields and any of the Tower Hamlets may gain admission to the Tower for one pound upon production of an Idea Store card.

London Characters

I supplemented my ever-growing collection of the Cries of London down the ages with this fine set of London Characters, cigarette cards by an unknown artist issued by Lambert & Butler in 1934.

Remarkably, The Chestnut Seller, The Boot Black, The Coffee-Stall Keeper, The Flower-Seller, The Ice-Cream Vendor, The Hyde Park Orator, The Newsboy, The Fish-Stall Keeper and The Pavement Artist survive, in very limited numbers and in differing forms. With references to black-shirts and the depression, these cards speak eloquently of the life of inter-war London, – “these enlightened days of stainless steel ” as they are described here with brash confidence. Yet, only yesterday, I saw a woman standing outside Liverpool St Station with a large handmade placard ,”2 Bedroom Flat to Sell,” which made me wonder if we might be on the brink of a street-selling revival in our capital.

“Baked Chestnuts!” – With the approach of autumn, the Baked Chestnut Man wheels his barrow with its glowing fire – over which the chestnuts pop and sizzle – to a frequented spot where the appetizing smell of his wares tempts pennies from the pockets of the passers-by.

A Billingsgate Porter – Beginning his day’s work at five am, the Billingsgate Porter has nearly finished his labours by the time the trains and buses are unloading hundreds of City workers onto Eastcheap and Fish St Hill – streets which are pervaded by the unmistakable sea-weedy and fishy odours which never entirely depart from the neighbourhood of the Monument.

The Boot-Black – In bygone days, the boot-black was found in every street corner. Each man had a large tin kettle for removing mud, two or three brushes and a very old wig – the latter being indispensable in a shoeblack outfit, very useful for whisking away dust and wiping off wet mud.

The “Cabby” – Drivers of “growlers” and “hansom” cabs are still to be seen, and may be recognised by their whole-hearted contempt for motors, their ready wit and and preferences for frequenting places associated with horses, such as Tattersall’s, Barnet Fair and Regent’s Park on Whit Monday.

“Catch ‘Em Alive!” – Modern hygiene with its slogan “Swat that fly” has done away forever with, “Catch ’em alive, O!” – the cry of the tall man in the tall hat which displayed a struggling mass of flies on its sticky trimming.

The Chair-Mender – The kerbside mender of chairs, who “if he had more money to spend would not be crying – “Chairs to mend!” is one of the neatest-fingered of street traders. Watch how deftly he weaves his strips of cane in and out – how neatly he finishes off each chair, returning it to the owner, “good as new.”

The Coffee-Stall Keeper – Many a drama of London-in-the-darkness is enacted at the coffee stall, which trundles its way each evening to its pitch where it remains until the city begins to awaken. Men and women of many types seek its hospitality during the hours of darkness, “down and outs” rubbing shoulders with revellers returning home in the early morning – and not a few are gladdened by a copper or two thrust into their hands by comrades a little better off than themselves.

The Cornet Player – A character never lacking in London streets is the Cornet Player, who provides a kind of magic that draws dogs like a magnet to him. He relies chiefly upon the licensed houses for his living, and can usually be recognised by his bulk.

The Covent Garden Porter – The Covent Garden Porter is the “Cockney of all the Cockneys” – good-humoured, hard working and possessed of a ready wit. Like his confrère at Billingsgate, he has been accused of being a “linguist” but although his speech may occasionally be forceful and picturesque, there is doubtless many a fox-hunting squire who might give him points and a licking!

The Crossing Sweeper – In bygone days, the Crossing Sweeper was a veritable “gentleman” of the road, who in many cases inherited his broom and his pitch from his parents. Tradition relates that the profession of a crossing sweeper was at one time a safe road to fortune.

The Flower Seller – The Flowers Sellers or perhaps more correctly “flower-girls” – for flower sellers in London always remain girls irrespective of age – are among the most picturesque of London characters. The flower-girl of Piccadilly, sitting beside her gay and fragrant basket in the shadow of “Eros” is the aristocrat of them all.

The Hyde Park Orator – Red-shirt, black-shirt, green-shirt and others – all are sure of an audience, especially on Sundays, when occupying their rostrums near Marble Arch. they are usually prepared for good-natured heckling – and often get it! Should things take a less friendly turn, there is always a “bobby” to keep his eye on things!

The Ice-Cream Vendor – The old-fashioned ice-cream barrow is dying hard, despite the rivalry of mass-production. Ice-cream “merchants” were usually Italian and the gaudy representations of Lake Como and the Rialto decorating his stall. Invariably called “Johnnie,” he met the demands of his of his youthful clientele, of messenger-boys and the like – to whom ice-cream makes an irresistible appeal – with exemplary patience and good humour.

The Kerbstone Trader – Dignity fails at the sight of the Kerbstone Trader. Aldermen, merchants and mere office-boys “fall” for his latest novelty “all made to wind up.” Red hot from an important board meeting, the Chairman of the Company relaxes on hearing the unspeakable sounds which proceed from the slow collapsing india-rubber pig.

The Newsboy – In some respects, the Newsboy reveals quite remarkable business instincts, chief among them his gift of shouting commonplace news in such a manner to make it sound important. He reads his own papers – how and when is a complete mystery – for his eye is always on a likely customer, but he can always tell you what Arsenal has done, and who is riding the favourite in the “big ‘un.”

The Old Fish-Stall Keeper – Wherever Londoners gather together, the fish-stall is found, whether in the crowded streets or one of the seas-side resorts where Cockneys take their doses of ozone. “Arry” and “Arriet” do much of their courting around the whelk stall, and comic singers owe much amusing patter to its delicacies, winkles and the necessary “extra” in the shape of a pin.

The Organ Grinder – The Organ Grinder and his monkey belong to a less sophisticated age than the present, with its bands of unemployed musicians and “tinned music” in various forms. This organist of the eighties was usually a native of Switzerland and instrument was a worn-out organ, under the weight of which he could sometimes scarcely stagger.

The Pavement Artist – He is above all an optimist – a sudden shower and all his day’s work is in vain! You may find him in any open space – near St Martin-In-The-Fields, Trafalgar Sq or on the Embankment – with his equipment of brightly-coloured chalks and a duster. The pavement artist is said to have been “the cradle” of some successful artists, but is certain that many who have known better days have resorted to this means of making a living.

The Quack Medicine Man – The “Medicine Man” of the street corner sells many things, from a cure for toothache to a remedy for broken hearts. Blessed with a wonderful gift of the gab and an endless store of ready wit, he is ready to expose all the secrets of Pharmacopoeia.

The Rag & Bone Man – The cry of “rags and bones” is familiar in the meaner streets, but often it is nit easy to recognise the words! Closely allied with the dealer in “rags” is the dealer of “old clo!” – the lady or gentleman who offers an aspidistra or a pot of ferns for an overcoat or a pair of trousers which has seen better days!

The Knife Grinder – Even in these enlightened days of stainless steel, the old-fashioned Knife Grinder may still be seen plying his trade in the London streets, with his well-known cry, “Knives, scissors, grind!” His lack of wares is more than compensated for by the picturesqueness of his outfit.

The Muffin Man – This is the Muffin Man, his bell clangs out its story of cosy fireside teas, and at the same time announces that summer is over! But history relates that ever since one of the fraternity was summoned for ringing his bell on a Sunday afternoon, the Muffin Man must choose with care the locality in which he goes selling the muffins.

The Sandwich Man – The Sandwich Man strikes a minor note in the great symphony of London life. His is the métier of the unfortunate, and sometimes his role as a perambulating advertisement is tinged with bitter irony. The shabby man directing all and sundry to the smart tailor, and the shaggy man advertising a first-class barber are bad enough, but what is one to say of the poor stray condemned to carry a board advertising the price of a first-class lunch with complete menu?

The Windmill Man – The Windmill Man will go down to posterity as a kind of “Pied Pier” who lured away the children from the noise and squalor of the streets to fairyland. The sound of his voice – for street vendors are still permitted to call their wares in the meaner streets – is a signal for a throng of scampering children to gather round him to exchange old bottles for gaily-painted windmills.

You may also like to take a look at these other sets of the Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders