David Power, Showman

David Power lives in a comfortable Peabody flat round the back of the London Coliseum and, with his raffish charm, flowing snowy locks and stylish lambswool sweater, he is completely at home among the performers of theatre land. Yet, although David may have travelled only a short distance to the West End from his upbringing in the East End, it has been an eventful and circuitous journey to reach this point of arrival.

Blessed with a superlative talent, both as a pianist and as a composer, David interrupted our conversation with swathes of melody at the keyboard – original compositions of assurance and complexity – and these musical interludes offered a sublime counterpoint to the sardonic catalogue of his life’s vicissitudes. Settled happily now with his third wife, David organises charity concerts which permit him to exercise his musical skills and offer a lively social life too. At last, winning the appreciation he always sought, David has discovered the fulfilment of his talent.

“I’ve done a lot of things in my time. All my family were boxers. In those days you had thirty or forty fights a week before you could make a living. It was a different world. Them days we had some good fights but they were hungry then. They punched the fuck out of each other but they were all friends too.

Me, I love boxing but I was a prodigy at the piano at the age of five. My mother, Lily Power, she couldn’t afford no piano lessons for me because we were poor. People have no idea how hard it was in the thirties and forties. I was born in Hounslow and my mother moved us back to Spitalfields where she was from.

My mum paid five shillings a week rent at 98 Commercial St but she wouldn’t let me answer the door when the rent collector came round. Today you couldn’t buy it for two million. Wilkes St was called the knocking shop because the brass went round there for the top class girls. They said, “Can we help you out, any way you like?” Itchy Park, next to the church, we called that Fuck Park – you could get it in there for sixpence. It was a wonderful, wonderful world.

Then I was evacuated to Worcester but I ran away about nine times. Each time, the police picked me up when I got to Paddington Station and put me on the train back again, I was nine years old. It was very funny.

They gave my mother an old pub in Worcester and she took in twenty armaments workers. There was no water, it was outside in the scullery. She charged one pound fifty a week for bed and breakfast and I used to get up at five-thirty to do the fires each morning in 1940. The most wonderful thing was when they brought gas into the house and we had a gas stove, and I didn’t have to worry about making up the fire each morning and heating the water for everyone for bath night on Friday. I got in a lot of trouble at school because I was Jewish and they used to say, “Show us your horns!” and that’s how I got into fighting.

I started work in Spitalfields Market when I was fourteen, I worked with a Mr Berenski selling nuts – peanuts and walnuts. The place was piled high with nuts! I had to stack them up with a ladder. I remember once the sack split and the nuts went everywhere and he chased me around the market. But Harry Pace, my cousin, he was a middleweight, he protected me.

I got a job in The Golden Heart playing the piano at weekends, earning one pound for two sessions. An old guy asked me to play, “When I leave the world behind,” and I thought, “He ain’t got long to go.” I earned three pounds, seventeen shillings and tuppence but, when my father discovered, he hit me round the ear and said, “You’ve been thieving!” Then my mother explained what I had been doing, and he took the money and gave me two bob.

After the war, my mother moved to Westcliff on Sea and that’s when she could afford two and sixpence for piano lessons for me, but by then I was much more interested in sport. As a child, I could play any music that I heard on the radio but, when I had my first lesson at ten years old, I thought crochets and quavers were sweets. There was a big Jewish community in Westcliff and I went to Southend Youth Club and started boxing there until I was called up for the army. I played football for Southend, we won the cup and I scored two goals. In the army, I sent my mum one pound a week home, but I was supposed to have been a concert pianist at eighteen. Fortunately, my Colonel liked music and I was in the NAAFI playing the piano and he asked me to play for the officers. They shipped me out to Hong Kong and Singapore and I played twice a month in the Raffles Hotel on Sundays and for the Prime Minister of Hong Kong.

When I came out the army, I was supported by Harriet Cohen, a concert pianist. I told her I was a ragged man but she wrote to the principal of the Guildhall School of Music. The professor told me to play flat, so I lay on the floor. I said, “You asked me to play flat, you fucking nitwit.” Then I went for an audition at the Windmill Theatre but they only offered me eight pounds a week for playing fourteen shows, so I jacked it in and did the Knowledge and became a cab driver, and got married in 1960. Then I decided to go into the markets and I worked in Covent Garden for twelve months as a porter, until my wife’s dad and I went into hotels – The Balmoral in Torquay and Hotel 21 in Brighton, but in the recession of the nineties I went bankrupt. We couldn’t compete with the deals offered by the big chains where businessmen used to bring their dolly birds at weekends.

Then I went on the road selling and I was earning three or four hundred pounds a week, especially in Wales. They didn’t know what a carpet was there. I once bought ten thousand dog basket covers for five pounds and sold them all at four for a pound as cushion covers in Pitsea Market. And that’s when I went into Crimplene, and then china, and then ties. Those were great days. Eventually, I went back in the taxi, worked like a slave, had a heart attack and died. Half of my heart is dead. I’ve been in and out of hospital with the old ticker ever since, so I decided to give something back by holding concerts for University College London Hospital. I do it all. I know talent when I see it and we have shows every month.

I never played the piano for twenty years, until ten years ago I went back to it – I wrote a piece of music when my wife died. I always wanted to be a pianist because music is something I get wrapped up in. A lot of people never believed I played the piano because I was so ragged, I had a ragged upbringing. If you come from the background that I came from, you’ve got keep putting money on the table. To be dedicated to music, you to have to be rich or a fool. I’m a born showman, that’s what they tell me, “David, you’re a showman.””

David (on the left) enjoys a picnic with his mother Lily and brothers and sisters in Itchy Park, Spitalfields in the nineteen thirties

David as a young boxer in the nineteen fifties

Concert Pianist Harriet Cohen encouraged David to become a professional pianist.

David Power, Showman

Pubs Of Wonderful London

In these cold grey days at the end of winter, I get a powerful urge to seek refuge in a cosy corner of an old pub and settle down for the rest of the afternoon. There are plenty of attractive options to choose from in this selection from the popular magazine Wonderful London edited by St John Adcock and produced by The Fleetway House in the nineteen-twenties.

The Old Axe in Three Nuns Court off Aldermanbury. It was once much larger and folk journeying to Chester, Liverpool and the North used to gather here for the stage coach.

The Doves, Upper Mall, Chiswick.

The Crown & Sceptre, Greenwich – once a popular resort for boating parties from London, of merry silk-clad gallants and lovely ladies who in the summer evenings came down the river between fields of fragrant hay and wide desolate marshes to breathe the country air at Greenwich.

At the Flask, Highgate, labourers from the surrounding farms still drink the good ale, as their forerunners did a century ago.

Elephant & Castle – The public house was once a coaching inn but it is so enlarged as to become unrecognisable.

The Running Footman, off Berkeley Sq, is named after that servant whose duty it was to run before the crawling old family coach, help it out of ruts, warn toll-keepers and clear the way generally. He wore a livery and carried a cane. The last to employ a running footman is said to have been ‘Old Q,’ the Duke of Queensberry who died in 1810.

The Grenadier in Wilton Mews, where coachmen drink no more but, at any moment – it would seem – an ostler with a striped waistcoat and straw in mouth might kick open the door and walk out the place.

The Spaniards in Hampstead dates from the seventeenth century and here the Gordon Rioters gathered in the seventeen-eighties, crying “No Popery!”

The Bull’s Head at Strand on the Green is an old tavern probably built in the sixteenth century. There is a tradition that Oliver Cromwell, while campaigning in the neighbourhood, held a council of war here.

Old Dr Butler’s Head, established in Mason’s Avenue in 1616. The great Dr Butler invented a special beer and established a number of taverns for selling it, but this is the last to bear his name.

The grill room of the Cock, overlooking Fleet St near Chancery Lane. It opened in 1888 with fittings from the original tavern on the site of the branch of the Bank of England opposite. Pepys wrote on April 23rd 1668, “To the Cock Alehouse and drank and ate a lobster and sang…”

The Two Brewers at Perry Hill between Catford Bridge and Lower Sydenham – an old hedge tavern built three hundred years ago, the sign shows two brewer’s men sitting under a tree.

The Old Bell Tavern in St Bride’s Churchyard, put up while Wren was rebuilding St Bride’s which he completed in 1680. There is a fine staircase of unpolished oak.

Coach & Horses, Notting Hill Gate. This was once a well-known old coaching inn, but it still carries on the tradition with the motor coaches.

The Anchor at Bankside. With its shuttered window and projecting upper storey, it enhances its riverside setting with a sense of history.

The George on Borough High St – one of the oldest roads in Britain, for there was a bridge hereabouts when Roman Legionaries and merchants with long lines of pack mules took the Great High Road to Dover.

The Mitre Tavern, between Hatton Garden and Ely Place. It bears a stone mitre carved on the front with the date 1546. Ely Place still has its own Watchman who closes the gates a ten o’clock and cries the hours through the night.

The George & Vulture is in a court off Cornhill that is celebrated as the place where coffee was first introduced to Britain in 1652 by a Turkish merchant, who returned from Smyrna with a Ragusan boy who made coffee for him every morning.

The Bird in Hand, in Conduit between Long Acre and Floral St, formerly a street of coach-makers but now of motorcar salesmen.

The Old Watling is the oldest house in the ward of Cordwainer, standing as it did when rebuilt after the Fire, in 1673.

The Ship Inn at Greenwich got its reputation from courtiers on their way to and from Greenwich Palace and in 1634 some of the Lancashire Witches were confined her, but now it is famous for its Whitebait dinners.

The Olde Cheshire Cheese – the Pudding Season here starts in October.

The Cellar Bar at the Olde Cheshire Cheese

The Chop Room at the Olde Cheshire Cheese

The Cellar Cat guards the vintage at the Old Cheshire Cheese. Almost under Fleet St is a well, now unused, but pure and always full from some unknown source. To raise the iron trap door which keeps the secret and to light a match and stoop down over this profound hole and watch the small light flickering uncertainly over the black water is to leave modern London and go back to history.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

The Taverns of Long Forgotten London

Alex Pink’s East End Pubs Then & Now

The Gentle Author’s Next Pub Crawl

The Gentle Author’s Spitalfields Pub Crawl

The Gentle Author’s Dead Pubs Crawl

The Gentle Author’s Next Dead Pubs Crawl

In Search Of Flower & Dean St

Contributing Writer, Gillian Tindall, went in search of Flower & Dean St

Fishman’s Tobacconist, Flower & Dean St, seventies, by Ron McCormick

It is a disappointing fact that some dwellings are built to be poor, you can find examples all over Britain. But in parts of London, once desirable streets had poverty imposed upon them. The streets of Spitalfields, whose early Georgian houses are now expensive and desirable, were from the Victorian period until well after the Second World War under this shadow. It is only thanks to the energies and determined actions of a few in the sixties and seventies that a number of these streets have survived, but many have not and one of these is Flower and Dean St.

In Tudor times, Spitalfields was actually fields beyond the City wall, though by the late Elizabethan days a sprinkle of individual wealthy gentleman’s houses began to dot the roadside up to Shoreditch and, by the reign of Charles I, there were more of them – typical ribbon development. This ceased during the Civil War but once peace was established, even before the Cromwells were seen off and Charles II was restored, builders got busy again in this desirable-almost-rural setting.

In 1655 two brothers called Fossan, one of whom was a goldsmith, acquired an odd-shaped chunk of land not far from an ancient, muddy track to brick fields, now Brick Lane. Much of the ground was used for tenter fields, where woollen cloth woven locally was hung up to dry. Already the City clothing industry was impinging on the rural land. The Fossans leased the land for ninety-nine years to two builders, John Flower and Gowan Dean. Such was the system under which most of Greater London was created over the next two hundred years. There they built Fossan St, whose name a generation later came to be misunderstood as ‘Fashion St,’ and gave their own surnames to the street just south of it.

Fashion St still exists with the handsome early eighteenth century Christ Church, Spitalfields, and its graveyard just to the north, but its present buildings are of a later date. The original Flower & Dean St is gone as if it had never been.

It must have been a pretty street and a respectable one for much of the next century, when it was mainly occupied by Huguenot silk-spinners. These were protestants who had come to England to find a more welcoming society than the Catholic France of Louis XIV. They arrived in far greater numbers in the 1680s when Louis tore up a legal agreement tolerating Protestantism and real persecution set in. Some arrived across the Channel in dangerously small boats, making their way into the Thames estuary and up the river by night. Nothing in the life of nations really changes.

These hard-working spinners and weavers flourished, and by the mid-eighteenth century many had established themselves in other businesses, entering prosperous British society. Those who remained began to do less well, imports of silk and cotton from India were damaging the home trade. By the middle of the century the houses in Flower & Dean St were being sub-divided into smaller lodgings. There were also questions about their stability, the brickies employer by Flower & Dean were said to have used inadequate mortar.

Fifty years later, the land east of Whitechapel was entirely built up with houses and these were extending further along the Mile End Rd. Within another generation, the hamlets set in countryside that was visible from the Tower of London would be turning inexorably into the great mass of the East End. To the prosperous residents of expanding West London, this might as well have been a foreign country.

In reality, of course, much of the East End was filled with decent hard-working people who themselves regarded such places as Flower & Dean St as dangerous slums. It was now where lodging houses offered a bed for a few pence a night and where, it was said, thieves felt at ease and prostitutes plied their trade, though it is unclear who would seek them out there.

Ford Maddox Brown, the painter, described it as ‘a haunt of vice… full of cut-throats’, and it was a place where policemen were said only to venture in pairs. But the street acquired a sudden and much more general fame when, in 1888, two women who lodged in there in different houses met their demise in the Whitechapel Murders. Enough was enough. With the not-entirely rational logic that has often been applied to places that get a bad reputation, it was decided the street should be pulled down.

Just to add to the drama, during demolition in 1892, two skulls and some bones were found in a box under the yard. More murder victims, it was at once assumed. In reality, the examination of the bones seems to have been cursory and it is likely these relics were from a field-burial hundreds of years earlier.

What rose in the place of Flower & Dean St was Rothschild Buildings, a massive tenement block bestowed on the large newly-arrived population of Jewish people from Eastern Europe. The bestowers were the Rothschild banking family, and it was a classic example of ‘four percent philanthropy’ – a charitable cause, yet one which nevertheless brought in a modest but steady income.

Moral views change and the improvements of one era attract the disapproval of later times. By the seventies, many of the descendants of the original Jewish occupants of the Rothschild Buildings were established in more salubrious northern suburbs and Bangladeshis arrived to take their place. The Buildings were steeped in soot and the lack of bathrooms in the flats was considered unacceptable. They were pulled down leaving only the grandiose brick archway. Today, the site is a dug-out games pitch at the end of the short stub of Lolesworth Close off Commercial St.

Just to the south is Flower & Dean Walk, a modern low-rise pedestrianised development, looking oddly out of place amidst the complex of old alleys and new tower blocks, with the raucous salesmanship of Petticoat Lane a few minutes away. I went for a stroll down there recently on a snowy day. There was a thin mist floating above the whiteness and it seemed as if the monstrously tall constructions that have transformed the City were dissolving into the sky, as if they were disappearing while the older, traditional buildings remained. Would that it were so!

Rothschild Buildings by John Allin, seventies

This bollard in Lolesworth Close is all that remains of Flower & Dean St

Entrance to the former Rothschild Buildings

Flower & Dean Walk

Flower & Dean Walk

Flower & Dean Estate opened by HRH The Prince of Wales on 18th July 1984

Gillian Tindall’s The House by the Thames is available from Penguin

You may like to read these other stories by Gillian Tindall

Memories of Ship Tavern Passage

At Captain Cook’s House in Mile End

The Costume & Mantle Worker

I spent an afternoon in the Bishopsgate Institute archive studying copies of The Costume & Mantle Worker, a bilingual journal in English and Yiddish for members of the United Ladies Tailors Trade Union. In Spitalfields, we are still aware of the former textile trade and I was especially fascinated by these adverts, reproduced below, which set me on a quest to discover which of these premises are still standing.

Formerly B. Weinberg, Printer, 138 Brick Lane

Formerly Folman’s Hotel & Restaurant, 128 Whitechapel Rd, Opposite Pavilion Theatre

The Gentle Author’s tailors’ stool

Formerly M. S. Rosenbloom & Co for sewing machines, 50 Brick Lane

Pages of The Costume & Mantle Worker courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

James Mackinnon, Artist

Twilight at London Fields, 2012

James Mackinnon’s streetscapes of the East End in general and London Fields in particular have captivated me for years. The seductive sense of atmosphere and magical sense of possibility in these pictures is matched by the breathtaking accomplishment of their painterly execution to powerful effect.

Remarkably, James is a third generation artist, with his uncle Blake and grandfather Hugh before him – which perhaps accounts for the classical nature of his technique even if his sensibility is undeniably contemporary.

We sat outside Christ Church, Spitalfields, one day and chatted about the enduring allure of the East End for artists. I was sorry learn that James had been forced to leave due to a combination of the rising rents and lack of recognition for his work.

Like several others I met while researching my book East End Vernacular, he is an artist who is genuinely deserving of appreciation by a much wider audience. It is very disappointing that the rewards for such a prodigiously talented painter as James Mackinnon are so little that he can no longer afford to be in the East End, and the East End is lesser for it.

“I grew up in South London in Lee Green and I used to go to the Isle of Dogs through the foot tunnel under the Thames and I was mystified by the area north of the river. Sometimes I would bunk off school with a sketchbook and go wandering there. It seemed a mysterious land, so I thought ‘What’s further up from the Isle of Dogs?’ I was a kid and I had been taken up to the West End, but I had never been to the East End and I sensed there was something extraordinary over that way.

I had always loved drawing and I got a scholarship in art to Dulwich College when I was eleven. The art department was wonderful and I got massive support, so I used be in the art block most of the time.

Later on, having left home and gone through college, there was a big recession and it was tough, all the students were scrabbling around for work, I had an epiphany. I was sat next to the Thames and I realised I just wanted to look at buildings and paint them. Since I was a child, buildings and their atmosphere, the feeling of buildings always had this resonance that I could not put my finger on.

As a kid, I was painting with poster paint and drawing with felt tips, and I was obsessed with the Post Office Tower. There was an art deco Odeon in Deptford that was derelict for years and it was demolished at the end of the eighties, and that had a huge effect on me. I sat in the back of my dad’s car and we drove past on the way up to London, and I would see this building and almost have a heart attack, I had such strong feelings about it. My God this thing is extraordinary, I am in love with it! It was falling to bits, it had pigeons sitting in the roof and it had wonderful art deco streamlining but it had this atmosphere, an elegance and a sadness. Even with the Post Office Tower, I felt it had this presence as though it were a person. That comes to the fore when you paint and you feel the place. You are not just concentrating on the architecture, it’s an emotional thing.

So with painting and drawing skills, I wanted to explore the landscape and often the hinterland. There is something compelling about going to a place you do not really know about – the mysterious world of places. The atmosphere of places is borne out of people and their residue, it’s about people living in a place.

By exploring, I was slowly drawn to where my heart was guiding me. In the early nineties, I moved to the East End because it was affordable and I had always wanted to explore there. And I was there until around 2013. I lived in Hackney and had a great time there, and made some great friends.

I was struggling as an artist, there was a lot of signing on the dole, but it was an act of faith, I knew it was what I had to do. I had always painted buildings.

I lived near London Fields and there is this little terrace of Georgian houses with a railway line and overhead electric wires, and there are some tower blocks in the distance, and you have all this grass. That was at the bottom of my road, it was such an interesting juxtaposition. A lot of East London landscapes have that, you might get a church sitting next to a railway line, next to tower block, next to the canal and a bit of old railing and some graffiti. That funny mixture. So I would just go and paint what I wanted. I painted what I was drawn to. For a long time, I was obsessed with Stratford. No-one had done anything to it at that time and I would go round the back streets and I roamed the hinterlands. I walked through to Plaistow and it is all part of a certain landscape that you find in the East End. To make a picture, you have got to find something that moves you and it can be something at the bottom of your road that resonates for you and makes the right composition for a painting. It’s hard to explain.

I had a go at having a studio but I was always a struggling artist so, when it came to rent day, it got tricky. It’s lovely having a studio but I could not afford it. I tried living in my studio for a bit to save money on the rent but the landlord found out and there was a cat and mouse game.

By the time I left, I think I had found myself. There is something in the painting that says it is me rather than anyone else and that has evolved from having done it for twenty years. I just about managed to survive. I realised I have got the tenacity and self belief. This is what I love. You find your path after a lot of struggle but it only comes by doing it. You realise that a great painting can come from something very ordinary, you can go for a walk and there might be something round the corner that knocks you out. There was a lot of that in the East End and I am still obsessed by it though it is changing hugely. Some of the landscapes have changed and some of the shops have gone. I miss Hackney in many ways but I do not miss struggling and rents going up. The area has changed.

So now I have moved to Hastings. I had a little boy and it became untenable to carry on living in the East End. I had no choice.”

Homage to James Pryde, 2009 (The Mole Man’s House)

Broadway Market

Shops in Morning Lane, 2014

Hackney Canal near Mare St, 2012

Canal, Rosemary Works 2014

Savoy Cafe, Hackney, 2012

James Tower, London Fields, 2012

Alphabeat, 2007

Paintings copyright © James Mackinnon

At Paul Rothe & Son, Delicatessen

It is my pleasure to co-publish this piece by Julia Harrison, author of the fascinating literary blog THE SILVER LOCKET. I am proud that Julia is a graduate of my blog-writing course.

There are only a few places available now on my course HOW TO WRITE A BLOG THAT PEOPLE WILL WANT TO READ on 25th & 26th March. Email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to enrol.

Portrait of Paul Rothe by Sarah Ainslie

I have known Paul Rothe’s Delicatessen & Cafe in Marylebone Lane for as long as I can remember. Back in the late sixties and early seventies, my mother used to travel up to town from Putney with me and my sister for a lunchtime treat at Paul Rothe’s before having our haircut by Mr John of ‘Charles, Bruno and John’ in their salon round the corner in Hinde St. I still have my hair cut by Andrew, who was a young apprentice in those days and now has his own salon, ‘Andrew K’, nearby on Marylebone St. He told me on my recent visit that during the salon’s heyday they used to cater for their clients and would often order sandwiches from Paul Rothe. I think it is these connections and the continuity they represent which make Paul Rothe so special to me.

Today, I work at Daunt Books on Marylebone High St and often, seeking a moment to myself at lunchtime, my footsteps lead me in Paul Rothe’s direction. Whether I am having a good day or a bad one, I know when I walk through the door a sense of inner peace will descend. Paul and his son Stephen will be there in their smart white grocer’s coats, lively smiles combined with looks of concentration on their faces as they deal expertly with the lunchtime rush. Office workers will be ordering take-aways, together with locals settling down for a bowl of homemade soup, while a happy customer chooses their favourite jam, chutney or sauce from the colourful range lining the shelves.

In the summer, snatches of music and occasionally operatic voices drift over from the rehearsal rooms across the road. Then I am drawn back to those innocent days long ago when my sister and I would look forward to window shopping at the Button Queen opposite, before ordering our homemade Liptauer and cucumber sandwiches at Paul Rothe, eating at the iconic fifties flip up seats and Formica tables where I sit today.

On a recent visit, in the company of Spitalfields Life Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie, I sat down with Paul to learn the story of his shop.

“Rothe is a German name. I am named after my grandfather who came from Saxony and worked his way over on a coal barge in 1898. Most German people at the end of the nineteenth century thought that the streets of London were paved with gold. My father didn’t know a lot about his father’s early life in Germany, except he met my grandmother in London. There was a flower shop in Jason’s Court called Schillers, they were German, and they introduced my grandmother and grandfather to each other. They got married and my father was born in 1915.

Paul started in partnership in Soho. The reason he opened there was that the man he was in partnership with was meant to open early, then they overlapped in the middle of the day and my grandfather would stay open late. But a lot of the customers were saying that his partner wasn’t in the store until about two hours after he should have been, so my grandfather decided to come here to Marylebone Lane and open on his own instead.

In my grandfather’s day, it was purely a retail shop, much smaller than you see now. There was a parlour at the back with a fireplace. My grandmother didn’t want the shop made bigger but my dad was always moaning that it was too small. After my grandfather had passed away, when his mother was on holiday, my father knocked the wall down and made that area part of the shop.

The shop opened on August 2nd 1900. We traded as a German deli. In one of the old photographs of the shop, you can see the words ‘Deutsche Delicatessen.’ We still make Liptauer, which is an Austrian cheese, and my dad made a cheese of his own invention with caraway seeds called ‘Kummelkase.’ A lot was imported from Germany and most of the staff spoke German. My grandfather was in the German army before he came over here and then he served in the British army.

In the Second World War, my father was a conscientious objector, he worked in the Middlesex Hospital on Mortimer St. He never heard his parents speak to each other in German, they only spoke in English. There was quite a German community round here then and we used to get a lot of customers coming to us because they felt at home. Until the First World War, we had ‘Deutche Delicatessen’ on the windows but they took that off. Now we have evolved and trade as an ordinary deli but at Christmas time we still have stollen and lebkuchen.

We lived in Harrow when I was a child and I will always remember coming in to the shop. We had the freestanding tables in those days. Dad had a pole attached to the ceiling which is still there, hidden behind the wooden beam where customers hang their coats, and we used to play ‘Here we go round the mulberry bush.’ I had a great time with my sisters dancing round the shop.

After the Second World War, we started becoming what you see today. A lot of other food stores opened up nearby and we had to change the way we operate. There was a Europa food store in Marylebone High St and, in recent years, Waitrose. Rather than having a general store where you could buy cornflakes and self-raising flour, we reduced our stock but specialised a lot more, so now we do every single jam and marmalade that Tiptree makes, for example, and all the sauces too. The brands that we stock, we have every option available. ‘Cottage Delight’ from Staffordshire is another one and ‘Thursday Cottage,’ which is a separate entity within Tiptree. They’ve got their own little factory and their own manufacturing process. We do well with Regent’s Park honey when it is in season in the summer.

The biggest change in how we operate was when we had parking restrictions imposed. In my dad’s day, anyone could pull up their car and do a week’s grocery shop but, because of the lack of parking, we don’t have that trade now. At Christmas time, we provide stocking fillers, little gifts that people will take home on the train. We don’t do a vast range, we specialise in particular things. My son is very artistic and he gets the aesthetics of the displays just right. He is computer literate too, which I am not, and looks after the social media side of things, putting the soup of the day up so people know what it is.

My father was very fortunate to buy the freehold of the shop when it came up for sale.There was an auction and no one else was bidding that day. Apparently, someone else had been interested but they got caught in traffic!”

Quite reluctantly, I leave Paul and his son Stephen to go back to my late shift at the bookshop. I am captivated by the stories he has shared. In his breezy, good-natured way, he brought to life not just the history of his family but a century of shopkeeping. Our bookshop has been in existence since 1910 and still has its original fittings, so I like to imagine book lovers of the Edwardian era choosing the latest volume, before walking down Marylebone Lane to buy their groceries at the Deutsche Delicatessen.

A photograph from 1914 showing ‘Deutsche Delicatessen’ on the windows. The girls were from the newsagents next door.

Paul Rothe’s grandfather in the early twenties, with his assistant Ernie

Robert, Karoline, Helmut and Thomas, c.1956

‘We stayed open during the war – my aunt ran the shop with one other member of staff called Thomas. As a young boy I remember we had Helmut who was a German prisoner of war who stayed over here – he always wore a little bow tie and we had a German student here. I would have been about ten and my grandmother was serving behind the counter.’

Robert Rothe, 1961

‘My dad was full of adrenaline, trying to serve quickly at lunchtime, he didn’t like anything that slows things down, so he didn’t do toast, wouldn’t do lettuce, he wanted everyone served quickly, he didn’t want a long queue.’

Three generations of the Rothe family on the shop’s hundredth anniversary

Stephen & Paul Rothe today

Stephen & Paul Rothe

Stephen demonstrates the fine art of a pastrami sandwich

Adding the pickles

The complete sandwich

Wrapping the sandwich expertly

A magnificent sandwich

David prepares the soup of the day freshly in the kitchen

‘At some point after the Second World War, my father started doing catering on the premises and we had freestanding tables with four chairs round each table, but you would get a group of six in and they would move the chairs around. We were already getting long queues and dad would have to stop serving and put it all back to where they belonged. So he ordered these that were screwed down to the floor so that people couldn’t move them. They are very fifties with their Formica tops. We had two more put in in 1964 and they’ve been here ever since.’

Stephen & Paul Rothe

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

PAUL ROTHE & SON, 35 Marylebone Lane, W1U 2NN

You may also like to read about

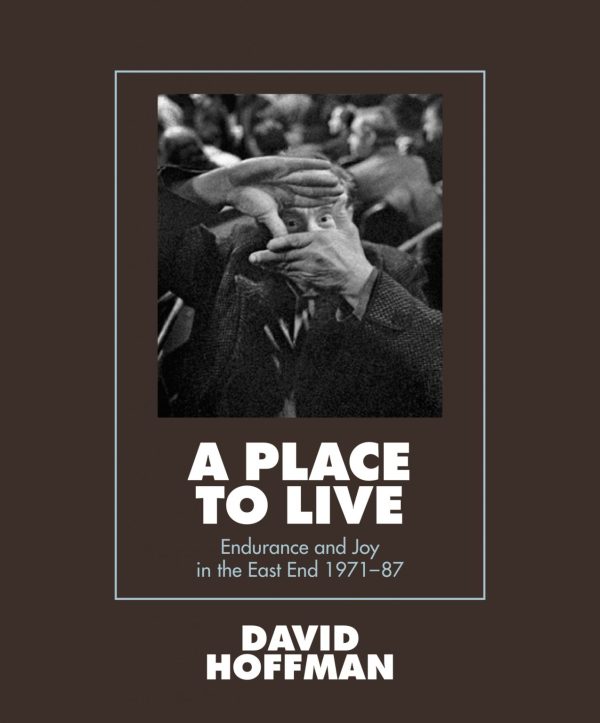

David Hoffman’s East End

David Hoffman undertook a significant body of photography documenting the East End in the seventies and eighties that I plan to publish this year as a book entitled, A PLACE TO LIVE, Endurance & Joy in Whitechapel, accompanied by a major photographic exhibition at House of Annetta in Spitalfields.

I believe David’s work is such an important social document, distinguished by its generous humanity and aesthetic flair, that I must publish a collected volume. I have a growing list of supporters for this project now, so if you share my appreciation of David’s photography and might consider supporting this endeavour, please drop me a line at spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

“I took these photographs thirty to forty years ago – they are all from the East End, mostly around Whitechapel and Spitalfields.

I was born in the East End, but my parents’ upward mobility whisked me out to suburbia and it was only in my twenties that I gravitated back to my roots. I was immediately entranced by the atmosphere of joy and dilapidation. It was the spirit of the people you see in these pictures that lifted my spirits and showed me the direction which my career has followed ever since.” – David Hoffman

Photographs copyright © David Hoffman

You may also like to take a look at