In Old Rotherhithe

Let me show you this 18th century graffiti on St Paul’s Cathedral…join my walk through the City of London. There are only two left this summer – Sunday 2nd July and Sunday 6th August at 2pm

Enjoy a storytelling ramble across the Square Mile, from the steps of St Paul’s through the narrow alleys and lanes to the foot of old London Bridge, in search of the wonders and the wickedness of the City of London.

Click here to book your tickets

St Mary Rotherhithe Free School founded 1613

To be candid, there is not a lot left of old Rotherhithe – yet what remains is still powerfully evocative of the centuries of thriving maritime industry that once defined the identity of this place. Most visitors today arrive by train – as I did – through the Brunel tunnel built between 1825 and 1843, constructed when the growth of the docks brought thousands of tall ships to the Thames and the traffic made river crossing by water almost impossible.

Just fifty yards from Rotherhithe Station is a narrow door through which you can descend into the 1825 shaft via a makeshift staircase. You find yourself inside a huge round cavern, smoke-blackened as if the former lair of a fiery dragon. Incredibly, Marc Brunel built this cylinder of brick at ground level – fifty feet high and twenty-five feet in diameter – and waited while it sank into the damp earth, digging out the mud from the core as it descended, to create the shaft which then became the access point for excavating the tunnel beneath the river.

It was the world’s first underwater tunnel. At a moment of optimism in 1826, a banquet for a thousand investors was held at the bottom of the shaft and then, at a moment of cataclysm in 1828, the Thames surged up from beneath filling it with water – and Marc’s twenty-two-year-old son Isambard was fished out, unconscious, from the swirling torrent. Envisaging this diabolic calamity, I was happy to leave the subterranean depths of the Brunels’ fierce imaginative ambition – still murky with soot from the steam trains that once ran through – and return to the sunlight of the riverside.

Leaning out precariously upon the Thames’ bank is an ancient tavern known as The Spread Eagle until 1957, when it was rechristened The Mayflower – in reference to the Pilgrims who sailed from Rotherhithe to Southampton in 1620, on the first leg of their journey to New England. Facing it across the other side of Rotherhithe St towers John James’ St Mary’s Rotherhithe of 1716 where an attractive monument of 1625 to Captain Anthony Wood, retrieved from the previous church, sports a fine galleon in full sail that some would like to believe is The Mayflower itself – whose skipper, Captain Christopher Jones, is buried in the churchyard.

Also in the churchyard, sits the handsome tomb of Prince Lee Boo. A native of the Pacific Islands, he befriended Captain Wilson of Rotherhithe and his two sons who were shipwrecked upon the shores of Ulong in 1783. Abba Thule, the ruler of the Islands, was so delighted when the Europeans used their firearms to subdue his enemies and impressed with their joinery skills in constructing a new vessel, that he asked them to take his second son, Lee Boo, with them to London to become an Englishman.

Arriving in Portsmouth in July 1784, Lee Boo travelled with Captain Wilson to Rotherhithe where he lived as one of the family, until December when it was discovered he had smallpox – the disease which claimed the lives of more Londoners than any other at that time. At just twenty years old, Lee Boo was buried inside the Wilson family vault in Rotherhithe churchyard, but – before he died – he sent a plaintive message home to tell his father “that the Captain and Mother very kind.”

Across the churchyard from The Mayflower is Rotherhithe Free School, founded by two Peter Hills and Robert Bell in 1613 to educate the sons of seafarers. Still displaying a pair of weathered figures of schoolchildren, the attractive schoolhouse of 1797 was vacated in 1939 yet the school may still be found close by in Salter Rd. Thus, the pub, the church and the schoolhouse define the centre of the former village of Rotherhithe with a line of converted old warehouses extending upon the river frontage for a just couple of hundred yards in either direction beyond this enclave.

Take a short walk to the west and you will discover The Angel overlooking the ruins of King Edward III’s manor house but – if you are a hardy walker and choose to set out eastward along the river – you will need to exercise the full extent of your imagination to envisage the vast vanished complex of wharfs, quays and stores that once filled this entire peninsular.

At the entrance to the Rotherhithe road tunnel stands the Norwegian Church with its ship weather vane

Chimney of the Brunel Engine House seen from the garden on top of the tunnel’s access shaft

Isambard Kingdom Brunel presides upon his audacious work

Visitors gawp in the diabolic cavern of Brunel’s smoke-blackened shaft descending to the Thames tunnel

John James’ St Mary’s Rotherhithe of 1716

The tomb of Prince Lee Boo, a native of the Pelew or Pallas Islands ( the Republic of Belau), who died in Rotherhithe of smallpox in 1784 aged twenty

Graffiti upon the church tower

Monument in St Mary’s, retrieved from the earlier church

Charles Hay & Sons Ltd, Barge Builders since 1789

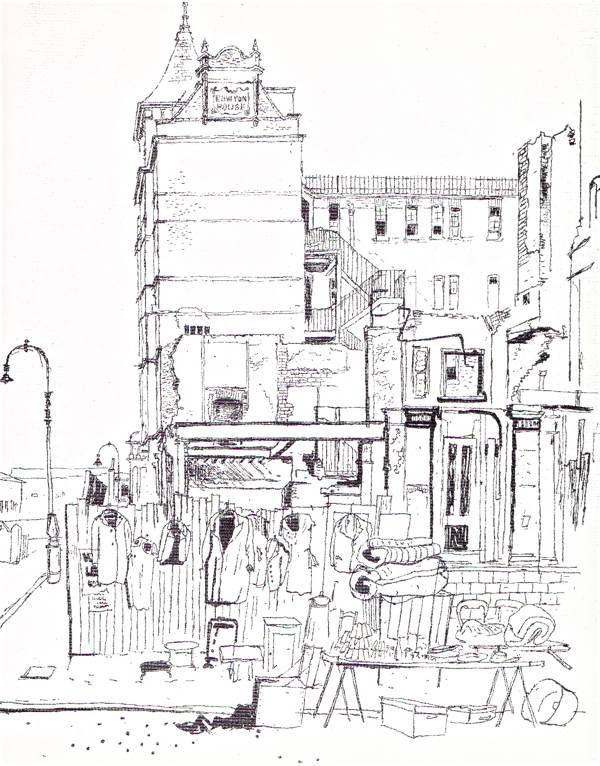

Peeking through the window into the costume store of Sands Films

Inside The Mayflower

A lone survivor of the warehouses that once lined the river bank

Looking east towards Rotherhithe from The Angel

The Angel

The ruins of King Edward III’s manor house

Bascule bridge

Nelson House

Metropolitan Asylum Board china from the Smallpox Hospital Ships once moored here

Looking across towards the Isle of Dogs from Surrey Docks Farm

Take a look at

Adam Dant’s Map of Stories from the History of Rotherhithe

and you may also like to read

On Father’s Day

Click here to book your tour tickets for next Saturday and beyond

My father

On Sunday – when I was a child – my father always took me out for the morning. It was a routine. He led me by the hand down by the river or we took the car. Either way, we always arrived at the same place.

He might have a bath before departure and sometimes I walked into the bathroom to surprise him there lying in six inches of soapy water. Meanwhile downstairs, my mother perched lightly in the worn velvet armchair to skim through the newspaper. Then there were elaborate discussions between them, prior to our leaving, to negotiate the exact time of our return, and I understood this was because the timing and preparation of a Sunday lunch was a complex affair. My father took me out of the house the better to allow my mother to concentrate single-mindedly upon this precise task and she was grateful for that opportunity, I believed. It was only much later that I grew to realise how much she detested cooking and housework.

A mile upstream there was a house on the other riverbank, the last but one in a terrace and the front door gave directly onto the street. This was our regular destination. When we crossed the river at this point by car, we took the large bridge entwined with gryphons cast in iron. On the times we walked, we crossed downstream at the suspension footbridge and my father’s strength was always great enough to make the entire structure swing.

Even after all this time, I can remember the name of the woman who lived in the narrow house by the river because my father would tell my mother quite openly that he was going to visit her, and her daughters. For she had many daughters, and all preoccupied with grooming themselves it seemed. I never managed to count them because every week the number of her daughters changed, or so it appeared. Each had some activity, whether it was washing her hair or manicuring her nails, that we would discover her engaged with upon our arrival. These women shared an attitude of languor, as if they were always weary, but perhaps that was just how they were on Sunday, the day of rest. It was an exclusively female environment and I never recalled any other male present when I went to visit with my father on those Sunday mornings.

To this day, the house remains, one of only three remnants of an entire terrace. Once on a visit, years later, I stood outside the house in the snow, and contemplated knocking on the door and asking if the woman still lived there. But I did not. Why should I? What would I ask? What could I say? The house looked blank, like a face. Even this is now a memory to me, that I recalled once again after another ten years had gone by and I glanced from a taxi window to notice the house, almost dispassionately, in passing.

There was a table with a bench seat in an alcove which extended around three sides, like on a ship, so that sometimes as I sat drinking my orange squash while the women smoked their cigarettes, I found myself surrounded and unable to get down even if I chose. At an almost horizontal angle, the morning sunlight illuminated this scene from a window in the rear of the alcove and gave the smoke visible curling forms in the air. After a little time, sitting there, I became aware that my father was absent, that he had gone upstairs with one of the women. I knew this because I heard their eager footsteps ascending.

On one particular day, I sat at the end of the bench with my back to the wall. The staircase was directly on the other side of this thin wall and the women at the table were involved in an especially absorbing conversation that morning, and I could hear my father’s laughter at the top of the stairs. Curiosity took me. I slipped off the bench, placed my feet on the floor and began to climb the dark little staircase.

I could see the lighted room at the top. The door was wide open and standing before the end of the bed was my father and one of the daughters. They were having a happy time, both laughing and leaning back with their hands on each other’s thighs. My father was lifting the woman’s skirt and she liked it. Yet my presence brought activities to a close in the bedroom that morning. It was a disappointment, something vanished from the room as I walked into it but I did not know what it was. That was the last time my father took me to that house, perhaps the last time he visited. Though I could not say what happened on those Sunday mornings when I chose to stay with my mother.

We ate wonderful Sunday lunches, so that whatever anxiety I had absorbed from my father, as we returned without speaking on that particular Sunday morning, was dispelled by anticipation as we entered the steamy kitchen with its windows clouded by condensation and its smells of cabbage and potatoes boiling.

My mother was absent from the scene, so I ran upstairs in a surge of delight – calling to find her – and there she was, standing at the head of the bed changing the sheets. I entered the bedroom smiling with my arms outstretched and, laughing, tried to lift the hem of her pleated skirt just as I saw my father do in that other house on the other side of the river. I do not recall if my father had followed or if he saw this scene, only that my mother smiled in a puzzled fashion, ran her hands down her legs to her knees, took my hand and led me downstairs to the kitchen where she checked the progress of the different elements of the lunch. For in spite of herself, she was a very good cook and the ritual of those beautiful meals proved the high point of our existence at that time.

The events of that Sunday morning long ago when my father took me to the narrow house with the dark staircase by the river only came back to me as a complete memory in adulthood, but in that instant I understood their meaning. I took a strange pleasure in this knowledge that had been newly granted. I understood what kind of house it was and who the “daughters” were. I was grateful that my father had taken me there, and from then on I could only continue to wonder at what else this clue might reveal of my parents’ lives, and of my own nature.

Me and my father

You may also like to read about

James Boswell’s East End

Click here to book your tour tickets for this Saturday and beyond

A few years ago, I visited a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. She pulled pictures off the wall and books off the shelf to show me his drawings, and then we went round to visit his daughter Sal who lives in the next street and she pulled more works out of her wardrobe for me to see. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

From the vast range of work that James Boswell undertook, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen thirties and the fifties.There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in the human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen-sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards,” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

You might also like to take a look at

In the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part One)

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part Two)

Adverts From The Jewish East End

Click here to book your tour tickets for this Saturday and beyond

Stefan Dickers, Archivist at Bishopsgate Institute showed me these adverts he found in an almanac from 1925 that originally came from Sandys Row Synagogue, evoking a lost East End world of Kosher Viands, Lodzer Cakes and Keating’s Powder.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to take a look at

Adverts from Stepney Borough Guide

The Night I Kissed Joan Littlewood

Click here to book your tour tickets for this Saturday and beyond

This is what happens when you try to carry a ladder the wrong way down a narrow alley, as Roy Kinnear is discovering in this frame from Joan Littlewood’s film Sparrows Can’t Sing.

You can see through the arch to Cowley Gardens in Stepney as it was in 1962. This is where Fred (Roy Kinnear’s character) lived with his mother in the film and here his brother Charlie (James Booth) turned up after two years at sea to ask the whereabouts of his wife Maggie (Barbara Windsor), finding that the old terrace in which he lived with Maggie had been demolished in his absence.

The drama revolves around Charlie’s discovery that Maggie has moved into a new tower block with a new man, and his attempts to woo her back. Perhaps there are too many improvised scenes, yet the film has a rare quality – you feel all the characters have lives beyond the confines of the drama, and there is such spirit and genuine humour in all the performances that it communicates the emotional vitality of the society it portrays with great persuasion. In supporting roles, there is Harry H. Corbett, Yootha Joyce, Brian Murphy and several other superb actors who came to dominate television comedy for the next twenty years. Filmed on location around the East End, many locals take turns as extras, including the Krays – Barbara was dating Reggie at the time – who can be seen standing among the customers in the climactic bar room scenes.

My favourite moment in the film is when Charlie searches for Maggie in an old house at the bottom of Cannon St Rd. On the ground floor in an empty room sits an Indian at prayer with his little son, on the first floor some Afro-Caribbeans welcome Charlie into their party and on the top floor Italians are celebrating too. Dan Jones, who lives round the corner in Cable St, told me that this was actually Joan Littlewood’s house where she and Stephen Lewis wrote the screenplay.

I once met Joan Littlewood at an authors’ party hosted by her publisher. She was a frail old lady then but I recognised her immediately by her rakish cap. She was sitting alone in a corner, being ignored by everyone, and looking a little lost. I pointed her out discreetly to a couple of fellow writers but, too awestruck by her reputation, they would not dare approach. Yet I loved her for her work and could not see her neglected, so I walked over and asked if I could kiss her. She consented graciously and, once I had explained why I wanted to kiss her – out of respect and gratitude for her inspirational work – I waved my pals over. We enjoyed a lively conversation but all I remember is that as we said our goodbyes, she took my hand in hers and said ‘I knew you’d be here.’ Although she did not know me or my writing, I understood what she meant and I shall always remember the night I kissed Joan Littlewood.

Watching Sparrows Can’t Sing again recently, I decided to go in search of Cowley Gardens only to discover that it is gone. The street plan has been altered so that where it stood there is not even a road anymore. Just as James Booth’s character returned from sea to find his nineteenth century terrace gone, the twentieth century tower where Barbara Windsor’s character shacked up with the taxi driver has itself also gone, demolished in 1999. Thus, the whole cycle of social and architectural change recorded in this film has been erased.

I hope you can understand why I personally identify with Roy Kinnear and his ladder problem, it is because I too want to go through this same arch and I am also frustrated in my desire – since nowadays there is a solid wall filling the void and preventing me from ever entering. The arch is to be found beneath the Docklands Light Railway between Sutton St and Lukin St. Behind this brick wall, which has been constructed between the past and the present, Barbara Windsor and all the residents of Cowley Gardens are waiting. Now only the magic of cinema can take me there.

At R. Russell, Brushmakers

Click here to book your tour tickets for this Saturday and beyond

Robert & Alan Russell, sixth generation brush makers

Take the Metropolitan Line from Liverpool St St Station all the the way to Buckinghamshire and after a ten minute walk through the small market town of Chesham you will arrive at the tiny factory of R.Russell– Brush Makers since 1840 – secreted in a hidden yard. Here you will find brothers Robert & Alan Russell, sixth generation brush makers, working alongside their eight employees making beautiful brushes by hand, the last of their kind in a town once devoted to the trade. Surrounded by beech woods, Chesham had a woodenware industry since the sixteenth century and brush manufacture began two hundred years ago as a means to utilise the offcuts from the making of wooden shovels for use in brewing.

The workshop at R.Russell is on the first floor looking down onto a garden with a tall pollarded tree and an old camellia in flower. Two large battered worktables fill the centre of the room where batches of brushes are lined up in different stages of manufacture. There are stacks of brushes with garish plastic bristles and racks of sweeping brushes with natural brown bristles. Over by the window is Alan’s work bench, overlooking the garden. And it was here that I joined him as he placed the bristles into the former to make a broom, speaking as he worked with breathtaking dexterity, occasionally pausing for thought and gazing out onto the garden below, yet without ceasing from his task.

“My father was Robert, his father was Stanley, before him was Robert, his father was George and then there was Charles. The origins are lost in the mists of time, but we know that in 1840 Charles Russell had a pub by the name of The Plough in Chesham, and he used to make a few brushes at the back of the pub and sold them to the customers. His son George was the first member of the family down in the records as a brush maker.

I’ve been making brushes since I was sixteen and I’ve been here forty years, After you’ve been doing it as long as I’ve been doing it, it’s quite relaxing. I’d much rather be making brushes than sat behind a desk doing office work, your mind goes off wherever you please.

My grandparents lived in the house at the front and the factory was a shed in their back garden. I came down here with my father at the age of six and he showed me how to make brushes. I used to make brushes with the waste off the floor, because the bristles were too valuable to spoil, but if you can make a proper brush with the waste then you really know how to make a brush! By the time I left school, I had a good training in brush making because I worked here every holiday and after school. My father never pushed me or my brother into it, but it was a natural progression because we got on well with Dad. I was made a partner at eighteen and my brother who’s older than me was already a partner.

When I started, we produced mainly paper-hanging brushes and dusting brushes for painters. We sold them to the kings of the market – the paintbrush makers – and they sold them to decorators. But they are all finished now the paintbrushes are made in China, so we lost our trade. We have gone back to how we were before, we make specialist brushes to order. It’s a niche market because there’s so few of us left. We are a handmade specialist brush maker. We are flexible and we have a lot of experience and we can turn our hands to anything. We made a brush for the National Trust recently, based on an original in a sixteenth century painting. It’s much more interesting although we are not making the money we used to make. We peaked just before the turn of the century, when the Chinese started selling their paint brushes here, and we’ve managed our decline since then. But I feel more confident now than for a long time. People are looking for something different and business is looking up. Meanwhile prices are rising in China and the quality is not always there, and people are prepared to pay for a better brush and they’re the people we’re supplying.

I don’t want to do anything else, as long as I can make enough to live on by doing this. I can’t imagine working for someone else, even though we work long hours here. My wife will tell you, I’d rather be here than spend a day at home decorating. I’m a brush maker. On my father’s grave we put “brush maker” not “brush manufacturer” because that’s what he was, a skilled man.”

Next door, in the office where the brothers prefer to spend the minimum amount of time, Robert, the elder brother, showed me the photographs of his forebears who worked here in the same trade before him. He confided that he and his brother never take a holiday at the same time and while one is away they speak on the phone every day.

Both brothers wore identical white short sleeve shirts with black trousers and white aprons, which were – I realised – the uniform of the brush maker, not so different from their predecessors photographed in the 1930s. After six generations, this pair have become as absorbed as anyone could be in this most unusual of occupations, a life devoted to brushes. And I could not resist asking Alan which brush he would be, if he were a brush, because I knew he would have a ready answer.

At once he came back with this reply -“If I was a brush, I’d be a Badger Softener because it’s something that’s looked after. It does something very special. It’s for marbling, to create the soft texture beneath the veins. It just softens the edges. It doesn’t do much, but you can’t do anything without it. It’s the sort of brush you’d buy once in a lifetime.”

Alan Russell tucks the bristles into the former – “I’d much rather be making brushes than sat behind a desk doing office work, your mind goes off wherever you please.”

Chess Vale Bowling Club, Chesham c.1910 – Old Bob Russell sits second from right in middle row with the watch chain while his son Stanley reclines in front.

Alan Russell uses his “flapper” to level off the bristles.

Robert & Alan’s grandfather Stanley Russell in the 1920s.

Ann Brett brushes out loose bristles. –“It’s nice to see something with the “Made in England” label on it.”

Robert & Alan’s great-grandfather Old Bob Russell in the 1930s.

Alan Russell checks the bristles are in alignment.

Bob & Stan Russell & a fellow brush maker in the 1930s.

Robert & Alan Russell – “people are prepared to pay for a better brush and they’re the people we’re supplying…”

The factory in the 1960s.

My souvenir, a beautiful handmade brush from R.Russell.

R.Russell brushes are available from Labour & Wait in Redchurch St

You may also like to read about

The Return Of Vicky Moses

Click here to book your tour tickets for next Saturday and beyond

Vicky outside the former Providence Row Shelter where she stayed as a ten-year-old in 1958

When Vicky Moses returned to Spitalfields for the first time in over fifty years while house-hunting she had the strange experience of encountering her younger self at the Providence Row Shelter in Crispin St, where she had once stayed as child. Then Vicky moved into a flat nearby in the Petticoat Tower and revealed that it is no accident that after all these years she chose to make her permanent home in Spitalfields.“The place feels comfortable to me,” she confirmed when I met her in Crispin St outside the former Providence Row Shelter.

“During the winter of 1958, my mother took myself, aged ten, with my sister and brother aged six and four, and a six-month-old baby, to London to get away from my violent father. Arriving at Victoria Station with just the housekeeping money, Mum had no option but to seek help. She went first to what is now The Passage, a charitable hostel in Carlisle Place in Victoria, but there was no help there for a family such as ours. Eventually – having walked right across London looking for somewhere to stay – by that evening we arrived at the doors of Providence Row in Spitalfields where we were given beds and this became our temporary home.

As a ten-year-old, I was able to take it all in and remember it well, even now. It was such a contrast to our suburban life, but we were safe and secure and with our mother, our rock.

My memories of Providence Row are these – From the street you went up steps to the door, and inside was a long large room with a huge wooden table running through the middle, and, on either side, along the walls, were wooden benches. Women and children were separated from the men who were downstairs.

Each night, before going to bed, we were given a mug of cocoa and a thick slice of bread and butter. We all went to bed about the same time. The dormitory had beds arranged, hospital-style, around the walls, facing into the room, and a double row ran down the centre. We were in the women’s dormitory, my sister and I sharing a single bed, Mum sleeping with my brother with the baby in-between. In the bed next to ours, an old woman slept fully clothed, muttering and snoring which I found most disturbing.

In the mornings, we went down for breakfast – a mug of tea and another thick slice of bread and butter. Then we had to go out as the refuge was closed during the day, so there was nothing to do but walk the streets.

Mum took this opportunity to show us the sights of London that were within walking distance. She showed us Billingsgate Fish Market and we went to St Paul’s, to Petticoat Lane Market where the crockery seller enthralled me with his banter and where I first tasted hot chestnuts, and to Fleet St and the Tower of London and Tower Bridge. I remember waiting and then eventually seeing the Bridge open and close for a ship to pass through.

There were the bomb sites too, fascinating places for a child. I read ‘An Episode of Sparrows’ by Rumer Godden when I was twelve and I saw the film version ‘Innocent Sinners’. It was all familiar to me because I knew the location, I’d lived there. ‘A Kid for Two Farthings’ was another film I saw not long after our stay – I must watch it again to relive those days, to see it again through my child’s eyes.

The days were very long and we had to be fed, which meant food on park benches. And it was cold. But eventually 5pm would come round and we could return to the refuge.

We should have been at school, of course, and my eleven-plus exam was approaching. I’d been learning long division of pounds, shillings and pence, so Mum taught me this at the shelter in the evenings. I knelt at the bench with a piece of paper on which Mum had written some sums and next to me were her spare coins to help me. The other residents must have thought this odd, but Mum was not to be deterred, the eleven-plus was important and preparation continued regardless of circumstances.

Next to us on the bench, sat another mother with her two daughters, the only other family I can remember. One daughter was my age, and the other was younger. I played with the older girl and we became friends, even though there was nowhere for us to go and play or even talk, other than by sitting beside each other on the bench.

The other residents came from an existence very different to mine. They were poor, desperate people from a Dickensian world – people whose problems were not solved by the new welfare state, but I didn’t feel threatened, and the nuns and lay staff were kind, and our Mum was our star.

When the time came for us to leave – we were moving on to stay with my uncle – I remember a nun came to the door to see us off. I can see her standing at the top of the steps. Mum needed to pop back inside to say goodbye to someone, and asked me to hold onto the pram and watch the others. She put her purse under the pram cover and went inside. Five minutes later she reappeared and went for her purse. It had gone. Someone had seen her go and distracted me from my task.

Those were strange days but ones I will never forget and, in many ways, I’m glad I had this experience though I wish the circumstances that led us there had been different.”

Vicky passed her eleven-plus exam in 1959.

Vicky (far right holding the baby) with her brothers and sisters in the spring of 1959, six months after their stay in the Providence Row Shelter.

The dormitory – Vicky’s mother and her two youngest children slept in the bed in the foreground, while Vicky and her sister shared the next bed in the front of the picture.

Sister Fidelma outside Providence Row’s Gun St entrance, pictured in Catholic Life, 1976.

Vicky stands in Gun St where Sister Fidelma once stood.

The shelter seen from the corner of Crispin St and Whites Row, a century ago.

Vicky is now a resident of Spitalfields and the shelter has been converted as student accommodation.

Extracts from a pamphlet produced by Providence Row in 1960.

Click here to read about the continuing work of Providence Row in Spitalfields.

You may also like to read about