In Bishopsgate, 1838

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS throughout November and beyond

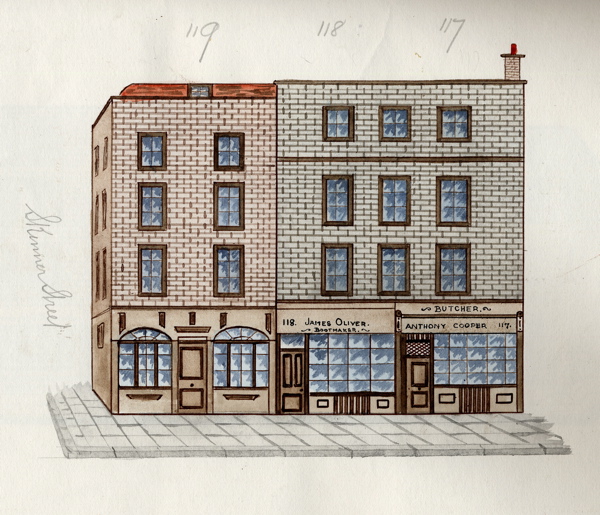

Before anyone ever dreamed of Google’s Street Views, there were Tallis’s London Street Views of the eighteen thirties, “to assist strangers visiting the Metropolis through all its mazes without a guide.” John Tallis created the precedent for a map which included pictures of all the buildings as a visual aid, commissioning the unfortunately named artist Charles Bigot to do the drawings and writer William Gaspey to create the accompanying text. Tallis had his imitators, evidenced by this beautiful set of anonymous watercolours of every single facade in Bishopsgate, Spitalfields, dated to 1838 and preserved in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

There is an infantile obsessive quality to these extraordinary paintings that drew my attention when I first came upon them, the degree of control and attention to detail in creating such perfect representations of the world is awe-inspiring. While there is a touching amateurism to the quality of the brushwork and lettering that recalls folk or outsider art, I cannot deny the attraction of the desire to record every facet of the world – because there is a strange reassurance to be gained from looking at these weird yet neat little pictures.

Although these views of Bishopsgate advertise their veracity by recording every single brick, I cannot believe it actually looked like this because the buildings are uniformly clean and well maintained, lacking any wear and tear. In contrast to the distorted chaotic nature of Google Street Views that record our contemporary cityscapes, there is a comic flatness in these drawings that are more reminiscent of street scenes in toy theatres and the houses you find on model railway layouts, tempting me to paste them onto matchboxes and create my own personal Bishopsgate.

Neat, tidy and eminently respectable, the early nineteenth century society envisioned by these innocuous facades is that of Adam Smith’s “nation of shopkeepers,” family businesses like that of Timothy Marr, the linen draper who opened up half a mile away upon the Ratcliffe Highway in 1808 and came to such a terrible end in 1811.

Yet although Bishopsgate itself is unrecognisably altered from the time of these drawings, the proportion of the buildings, providing a shop on the ground floor, with family accommodation and sometimes workshops above, is still familiar in Spitalfields today. And the two stocks of brick used, red brick and the London yellow brick remain the predominant colours over one hundred and fifty years later.

Sir Paul Pindar’s House, illustrated in the penultimate plate, is the lone survivor from the time before the Fire of London when Spitalfields was a suburb where aristocrats had their country residences. Today the frontage can be viewed at the Victoria & Albert Museum where it was moved in 1890.

Named Ermine St by the Romans, for centuries Bishopsgate was the major approach to the City of London from the north leading straight down to London Bridge, and the saddler & harness makers and coach builders present in the street reflect the nature of this location as a point of arrival and departure.

There are some age-old trades recorded in these pictures that survived in Spitalfields until recent times, upholsters, umbrella makers and leatherworkers, while the straw hat makers, cutlers, dyers, tallow sellers and corn dealers went long ago. Yet we still have plenty of hairdressers today, though I feel the lack of a fishmonger sorely. Let me admit, my favourite business here is Mr Waterworth, the plumber. He could become a credible addition to a set of Happy Families, along with all his little squirts.

You can see the frontage of Sir Paul Pindar’s House today at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

That’s quite a find! Glad to see that some of the business names are female.

Love reading your blog entries. A friend from Berlin, Germany.