Remembering Jessica Strang

Contributing Writer Rosie Dastgir recalls her friend and neighbour in Whitechapel, the remarkable Jessica Strang, photographer & activist (1938–2021)

Portrait by Mervyn Peake, 1959/60

I first met Jessica Strang, a South African photographer and campaigner, in the late nineties when she became my neighbour round the corner in Whitechapel. The old East End weaver’s house with its light-filled loft, formerly used by workers at their looms, was ideal for Jessica. It was a space filled with a lifetime’s repository of photos, art works, furniture, found objects, postcards and bric-a-brac. She was a magpie for visually interesting and arresting things.

Here was a Basquiat-style painting by one of the neighbours. There was a portrait of an Afghan by Irma Stern, the celebrated South African artist, that had been purchased by her father at a charity auction to raise money for the defence at the 1956 Treason Trial of Nelson Mandela and others in Johannesburg. These works sat happily amongst her dizzying array of things: the little wire bicycle sculptures from South Africa, the beaded red ribbon for AIDS remembrance brooches, the hand-carved wooden gorilla, the clock designed by her son, the plethora of postcards, bottle tops, bags and textiles. Every piece carried a story which she recounted to me.

Jessica was born and grew up in a middle class family in Johannesburg, the daughter of German refugees. She came to London in the late fifties to study Graphic Design at the Central School of Art & Design but attended Mervyn Peake’s Fine Art classes instead. After college, she was one of those who set up the design group that became Pentagram where she worked with architect, Theo Crosby.

She started taking photographs in earnest, creating a library of Crosby’s architectural works, and developing her own work into an astonishingly expansive collection of photography. She was never without a camera in hand, documenting people, places and things wherever she went. Nothing and nobody escaped her eye, it was a compulsion that reflected her zest for capturing life before it outran her. She relished everything and wanted to save it all. She was eager to photograph the home delivery of my first child in a pool, but in the end – luckily for me – she settled for an atmospheric shot outside our house. It was hard to say no to Jessica.

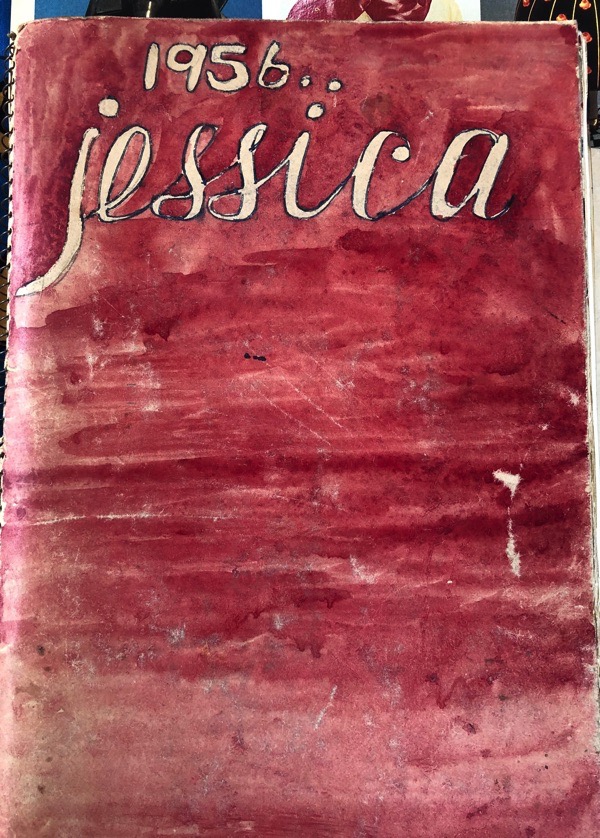

Her hunger for the world existed from early girlhood. That same keen purpose is evident in the scrapbook journals she kept as a teenager, bright collages of glued-in tickets, memos, theatre programmes, souvenirs from her trip to Europe on the BOAC Comet, all carefully collated alongside her pithy entries about her job at Stuttafords, the Johannesburg department store known as the Harrods of South Africa, where she worked to save for her travels abroad.

From the sixties, Jessica was active in the Anti-Apartheid movement, joining regular protests outside the South African embassy in Trafalgar Sq. She and her father, Edward Joseph, raised funds for the London staging in 1961 of the black South African jazz hit musical King Kong starring Miriam Makeba, about the life and times of boxer, Ezekiel Dlamini, set against the backdrop of the township, Sofiatown. Throughout the nineties, Jessica raised scholarships for black South African artists to come to London. This was a harsh time for these artists and she supported and befriended them while in a strange land, arranging space to create their art while sharing the sights and sounds of her adopted city, as well as her own kitchen for suppers and chat.

Jessica first visited Europe in 1952 on the fabled and short lived Comet BOAC aircraft, whose many delights she recorded in one of her journals. She brought fresh fruit from South Africa for her aunt in London, only to be apprehended at customs. In those days, when oranges were prized and seasonal, the prospect of giving them up made her cry so persuasively that the duty officer caved in and waved her through. She never shied away from wrangling her way past an official.

In the early seventies, she bought a small parcel of land on Hereford Rd in Notting Hill and commissioned her old boss from Pentagram to design her a house. In the aftermath of a broken first marriage, she stipulated that it should be a place where nobody could stay for more than two nights. Theo Crosby rose to the challenge. With its tiny spare room and open plan, high ceilings and exposed brick, her little home was ideal for her and her burgeoning work. When Tim Oliver moved in later, she insisted he must share the place with her two cats and, soon afterwards, Cleo was born. By the time their second child Orlando arrived, the space was squeezed so they upped sticks for a bigger house in Ladbroke Grove.

During this phase, she developed her photography by travelling round the world accompanying Tim to medical conferences, and in 1984, her first book came out, Working Women: A Photographic Collection of Women with a Purpose. She also worked as Dick Bruna’s Miffy licensing agent, ensuring that the Dutch rabbit was rendered correctly and not commercially exploited.

It was after her elderly mother’s death and the children had left home, that Jessica and Tim decided to move to the East End, so that Tim, an oncology consultant and professor, could walk to work at the nearby Royal London Hospital after decades of commuting on the Underground. Jessica had been reluctant to move to the area until that point, perhaps because of its associations with her grandfather who had fled from pogroms to London in 1904, only to be orphaned when his parents died in a refugee camp in Goodman’s Fields. He had been sent to live in Leeds with a kindly family who encouraged him to explore his Jewish background and he had emigrated to Bulawayo where he found a small community around the synagogue.

Ever since she left Hereford Rd, Jessica’s wish had been to find another site to design and build a house for her photography collection and her accumulation of artefacts. She searched and searched but it seemed impossible. So she and Tim settled in the Whitechapel weaver’s house on Halcrow St until she discovered Brody House, an Art Deco sequin factory in Aldgate near Petticoat Lane. Her flat there was a sun lit eyrie on the fifth floor, with panoramic views across the East End and a terrace for her olive trees, geraniums, and ferns.

There were frequent visitors, old and new friends, colleagues and neighbours who gathered regularly for suppers and drinks. These were boozy and convivial evenings when her raucous laughter floated out into the night. Jessica was forceful, loving and determined: nobody could resist the broad wingspan of her friendship.

In the first years of this century, Jessica suffered a burst pituitary tumour but recovered remarkably. Thanks to Tim, she kept travelling, walking everywhere and photographing the unfurling world. She visited us in New York City in 2011, after our family left Whitechapel, and she was immediately at home in the hectic streets of Brooklyn. An inveterate traveller and adventurer, she winkled out curiosities in the Atlantic Avenue shops and photographing every sight and incident that caught her eye.

By now, her library of images had increased to over 400,000 images. Tim found a PhD student to help her document and catalogue her photos. Still, her work did not abate, as if some hidden part of her knew what to do and kept going, even after a stroke caused loss of speech and dementia crept up on her in her final years.

Jessica died at home in June with her family around her, surrounded by her life’s work in its dazzling variety. She is survived by her husband Tim, a professor emeritus at Queen Mary University, her daughter, Cleo, a doctor in South London, and her son, Orlando, an architect based in Singapore.

Jessica Strang & Tim Oliver in the seventies

Jessica’s photos of her tiny house in Notting Hill designed by Theo Crosby

Jessica & Tim with their children, Cleo & Orlando

Jessica in Petticoat Lane in recent years

Jessica’s view from the top of a sequin factory in Aldgate

You can see Jessica Strang’s photography on Instagram @ jessicastrang_photolibrary

You may like to read these other stories by Rosie Dastgir

Rosie Dastgir’s Letter From Tokyo

At Tjaden’s Electrical Repair Shop

Gulam Taslim, Funeral Director

A very evocative and moving statement. Maybe my parents might have met her moving on the edge of Central school or Pentagram circles.

What an incredibly interesting story.

Love & Peace

ACHIM

Truly a life well lived. Thank you for telling her story GA.

Hetty, do have a look at her IG feed – your parents might recognise her or her work!

In the 1970’s, I stayed many times at the Brufani Hotel in Perugia so it is wonderful to see this reminder. Oh, and a very interesting profile of Jessica.

Such an interesting woman. She was clearly blessed.

What a vibrant person and fascinating artistic trajectory. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for posting this… what an amazing person, who lived such a creative life.

Incredible to read this moving account of cleo’s mum and her work – I am not surprised that she has also been an activist for making life better for those around her as her daughter and son in law both are! My thoughts are with the family.

I worked in Pentagrams photographic department in the early 1970s and remember Jessica well. She was a lovely, hard working person.

Thank you for this unexpected post. A lovely and talented family, a good friend to my late wife and her son was at primary school with my daughter

Grateful for this post. Treasured memories of Jessica, and her fabulous family, to include her beautiful mother. Her home was always, a home. Meals were adventurous. Her family, loved beyond measure. Enjoyed taking Josephine, nee Cleo, and Orlando to the New Year’s celebration at the Albert Hall. Wishing Tim, and her beloved, abundant joy as she will always be celebrated.