Neville Turner In Elder St

On the second day of British Land’s public exhibition for their controversial redevelopment of Norton Folgate, I publish the story of Neville Turner whose family lived in Elder St before British Land partly demolished it in the seventies. The exhibition is open today from midday until 5pm, and readers are encouraged to go along and record their comments in writing – further details below.

This is Neville Turner sitting on the step of number seven Elder St, just as he used to when he was growing up in this house in the nineteen forties and fifties. Once upon a time, young Neville carved his name upon a brick on the left hand side of the door, but that has been replaced now that these are prized buildings of historic importance. Yet Neville counts himself lucky that the house he grew up in still stands, after it came close to demolition when half the street was swept away by British Land in the seventies.

At the time Neville lived here, the landlords did no maintenance and the buildings were dilapidated. But Neville’s Uncle Arthur wallpapered the living room with attractive wisteria wallpaper, which became the background to the happy family life they all enjoyed, in the midst of the close-knit community in Elder St during the war and afterwards. Subsequently, the same wisteria wallpaper appeared as a symbol of decay, hanging off the wall, in photographs taken to illustrate the dereliction of Elder St when members of the Spitalfields Trust squatted it to save the eighteenth century houses from demolition.

It was only when an artist appeared – one Sunday morning in Neville’s childhood – sketching the pair of weaver’s houses at number five and seven, that Neville first became aware that he was growing up in a dwelling of historic importance. Yet to this day, Neville protests he carries no sentiment about old houses. “This affection for the Dickensian past is no substitute for hot and cold running water,” he admitted to me frankly, explaining that the family had to go the bathhouse in Goulston St each week when he lived in Elder St.

However, in spite of his declaration, it soon became apparent that this building retains a deep personal significance for Neville on account of the emotional history it contains, as he revealed to me when he returned to Spitalfields this week.

“My parents moved from Lambeth into number seven Elder St in 1931 and lived there until they were rehoused in 1974. The roof leaked and the landlords let these houses fall into disrepair, I think they wanted the plots for redevelopment. But then, after my parents were rehoused in Bethnal Green, the Spitalfields Trust took them over in 1977.

I was born in 1939 just before the war began and my mother called me Neville after Neville Chamberlain, who she saw as the bringer of peace. I got a lot of stick for that at school. I had two elder brothers, Terry born in 1932 and Douglas born in 1936. My father was a firefighter and consequently we saw a lot of him. I felt quite well off, I never felt deprived. In the house, there was a total of six rooms plus a basement and an outside basement, and we lived in four rooms on the ground floor and on the first floor, and there was a docker and his wife who lived up on the top floor.

My earliest memory is of the basements of Elder St being reinforced as air raid shelters in case the buildings collapsed – and of going down there when the sirens sounded. Even people passing in the street took shelter there. Pedlars and knife-grinders, they would bang on the door and come on down to the basement. That was normal, we were all part and parcel of the same lot. I recall the searchlights, I found it interesting and I wondered what all the excitement was about. War seemed quite mad to me and, when it ended, I remember the street party with bonfires at each end of the street and everybody overjoyed, but I couldn’t understand why they were all so happy. None of the houses in Elder St were damaged.

We used to play out in the street, games like Hopscotch and Tin Can Copper. All the houses had a door where you could go up onto the roof and it was normal for people in the terrace to walk along the roof, visiting each other. You’d be sitting in your living room and there’d be a knock on the window from above, and it was your neighbours coming down the stairs. As children, we used to go wandering in the City of London, and I remember seeing typists typing and thinking that they did not actually make anything and wondering, ‘Who makes the cornflakes?’ Across Commercial St, it was all manufacturing, clothing, leather and some shoemaking – quite a contrast.

After the war, my father worked as a bookie’s runner in the Spitalfields Market, where the porters and traders were keen gamblers, and he operated from the Starting Price Office in Brushfield St. He never got up before ten but he worked late. They were not allowed to function legally and the police would often take them in for a charge – the betting slips had to be hidden if the police came round. At some parts of the year, we were well off but other parts were call the ‘Kipper Season’ which was when the horse-racing stopped and the show-jumping began, then we had very little. I knew this because my pocket money vanished.

I joined the Vallance Youth Club in Chicksand St run by Mickey Davis. He was only four foot tall but he was quite a strong character. He was attacked a few times in the street on account of being short and a few of us used to call up to his flat above the Fruit & Wool Exchange, so that he could walk with us to the club, but then he got ill and died. Tom Darby and Ashel Collis took over running the club, one was a silversmith and the other was a passer in the tailoring trade. We did boxing, table tennis and football, and they took us camping to Abridge in Essex. We got a bus all the way there and it only cost sixpence.

I moved on to the Brady Club in Hanbury St – it changed my outlook on life. They had a music society, a chess society, a drama society and we used to go to stay at Skeate House in Surrey at weekends. If you signed up to pay five shillings a week, you could go on a trip to Switzerland for £15. Yogi Mayer was the club captain. He called me in and said, ‘This is a private chat. We are asking every boy – If you can’t manage the £15, we will make up the shortfall. But this is between you and I, nobody else will know. I believe that everybody in the East End should be able to have an overseas holiday each year.’ It endeared him to me and made a big impression. When I woke in Switzerland, the sight of the lakes and the mountains was such a contrast to Elder St, and when we came back from our fortnight away I got very down – depressed, you would say now. I was the only non-Jewish person in the Brady Club, only I didn’t realise it. On one of the weekends at Skeate House, I did the washing up and dried it with the yellow towel on a Saturday. But Yogi Mayer said, ‘I won’t tell anyone.’

A friend of my brother’s worked in Savile Row and I thought it would be good for me too. I went to French & Stanley just behind Savile Row and they said they did need somebody but not just yet. So then I went to G.Ward & Co and asked if they wanted anybody, and there was this colonel type and he said, ‘Start tomorrow!’ I was fifteen and a bit, I had left school that Christmas-time. It lasted a couple of years and they were good to me. The cutter would give you the roll of work to be made up and say, ‘It’s for a friend of yours, Hugh Gaitskell.’ When I asked the manager what this meant, he said, ‘We’re Labour and they’re not.’

In 1964, I left Elder St for good, when I got married. I met my wife Margaret at work, she was the machinist and I was the cutter. She used to bring in Greek food and I liked it, and she said, ‘Would you like to come and have it where I live? You’ll have no excuse for forgetting the address because it’s Neville Rd!’

When I started in tailoring, the rateable value of the houses in Elder St was low because of the sitting tenants and low rents, and nobody ever moved. We thought it was good, it was a kind of security. The money people had they spent on decorating and, in my memory, it was always warm and brightly decorated. There was a good sense of well-being, that did seem generally to be the case. We were offered to buy both the houses, five and seven Elder St, for eighteen hundred quid but my father refused because we didn’t want them both.”

Neville with his grandmother.

Neville’s mother Ada Sims.

Neville’s father Charles Turner was in the fire service during the war (fourth from left in back row).

Neville as a schoolboy.

Neville’s ration book.

Coker’s Dairy in Fleur de Lis St used to take care of their regular customers – “If you were loyal to them, they’d give you an extra piece of cheese under the counter.”

Neville aged eleven in 1951, photographed by Griffiths of Bethnal Green.

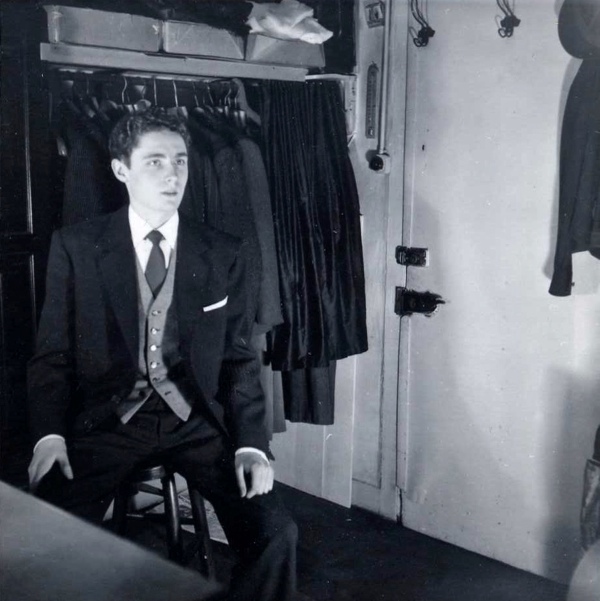

Neville at Saville Row when he began his career as a pattern cutter at sixteen.

Neville’s father Charles owned the only car in Elder St – “We had a car in Elder St when nobody had a car in Elder St, but it vanished when we had no money.”

Neville as a young man.

A family Christmas in Elder St, 1968 – Neville sits next to his father at the dinner table.

Neville’s father, Charles.

Neville and Margaret.

Margaret and Minas.

Neville, Margaret and their son Minas.

Neville’s Uncle Arthur who hung the wisteria wallpaper.

Minas and Terry.

The living room of number seven photographed by the Spitalfields Trust in 1977 with Uncle Arthur’s wisteria wallpaper hanging off the walls.

Neville Turner outside number seven Elder St where he grew up

![Blossom Street Exhibition Invitation[1]](https://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Blossom-Street-Exhibition-Invitation11.jpg?resize=600%2C695)

![Blossom Street Exhibition Invitation[2]](https://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Blossom-Street-Exhibition-Invitation2.jpg?resize=600%2C781)

Readers are encouraged to attend and record your comments in writing at the exhibition

You may also like to read about

I have been reading the website of British Land – they sell themselves as heroes and do-gooders, rather sickening. I hope that the protests will stop them on time. Valerie

Those photos remind me of my past as well, as I’m the same age as Neville, all sitting round the table at Xmas time everybody seemed so happy then not like now give me give, it’s uncanny I looked exactly the same as Neville as a schoolboy. My Father worked round there

In a cabinet makers workshop all he’s life.

Roger

D’you think British Land really want to know our thoughts? Or are they doing the ‘consultation’ merely as a ‘tick the boxes’ thing?

Between 1951 and 1958 our house was No 7 Blossom Street which runs parallel with Elder Street. Some of the things I remember that Neville may as well are Benny’s shop in Folgate Street; Falcus Builders yards. The remains of the bombed Golden Key chemist. A large WW2 water reservoir by Folgate Street. The stables in Folgate Street. Bardiger the furriers on the corner of Blossom St. The dairy in Fleur de Lys Street. The police officer on point duty under floodlight when it was dark in Commercial Street at the junction with Hanbury Street. I’m younger than Neville and wasn’t around during WW2, but my mother told me that one of the most marvelous experiences of her life was at the end of the war going into Norton Folgate when all of the street lights were switched back on after 6 years of darkness.