A Long Way From Spitalfields

Ten years ago this morning, I woke in an apartment in New York City. It was around eight thirty when my friend called from outside the bank in Midtown, where he had gone to deposit cheques. He had left early to be there at opening time and, as he was standing in line waiting for a teller, he saw on the television that there was a fire in one of the towers at the World Trade Centre.

I got out of bed and climbed up onto the flat roof of the apartment. It was a beautiful day, clear and bright with a blue sky after days of rain and cloud, and the humidity which overwhelms Manhattan in July and August had cleared. Although most people try to avoid New York in the Summer, and residents who have the option seek refuge in beach houses, it is my favourite time of year in the city. The one time when the pace slows, languor prevails, and there is peace in the shadowy air-conditioned buildings where people linger to avoid the baking temperature and blinding light outside in the streets.

Summer was drawing to an end and there would be no more of the trips to Long Island that had punctuated my time in the City. Just a week earlier, on Labor Day, which marks the change in the season, the beaches had closed for the year.

I stood on this same roof on July 4th and watched the fleet line up in the East River, admiring the firework display as I ate dinner with friends. Looking across Manhattan that morning, I could see the distant plume of smoke from the westerly of the towers. It did not mean anything to me then, but I was puzzled how it could have happened, so I went downstairs and switched on the television. The television was reporting a plane had crashed into the tower. It was an extraordinary event for which the news anchor had no explanation, and so I went back to bed and dozed again.

I was awoken by the return of my friend who had cycled back from his errand at the bank. People were getting really excited about this fire, he told me, and he switched on the television again. For the first time, I sensed the panic and helplessness which was to envelop the city that day, as the presenters struggled to find words and keep their cool in the face of inexplicable and unprecedented events.

Then came the strangest moment of television I ever saw. Upon the screen, a plane jetted out of nowhere and disappeared into one the towers. “That’s a re-run, you’re seeing here, of the plane hitting the tower that we reported earlier,” commented the news-anchor, only to swallow her words – almost choking – as she exclaimed, “Oh no! That’s not a re-run, that’s another plane.”

Exactly a week earlier, at eight thirty in the morning, I visited the World Trade Centre accompanying my friend who was applying to an office there for a street traders’ licence. We came through the subway which opened up into a shopping mall and emerged onto the plaza directly beneath the towers. I recalled the first time I came to New York and stood at the top. Stretching my arms between those external struts and gazing down upon Manhattan from such a height, it was as if looking from the window of an aeroplane. My birthday was in a few days and we vowed to return to the top for a celebration, but we did not go back.

Once the second plane hit the towers, the tenor of events changed. Very quickly, reports came in of hijackings and other planes unaccounted for. I went back up onto the roof of the apartment and looked again to confirm the reality of the television news with my own eyes. Now there were two plumes of smoke in the sky, and sirens erupted through the streets as fire crews and police hurtled down the avenues of Manhattan. I returned to the television and stayed there, compelled. I had a pocket email machine and I was able to write messages to everyone in London to let them know I was alright, before the lines went dead.

A campaign was underway, something I could only comprehend through reference to science fiction such as “The War of the Worlds.” An attack had commenced that morning without indication how long it would last. As I sat there in shock at the accumulating reports of the plane hitting the Pentagon and the crash of United 93, a dread grew inside me. There was no reason to assume that this would not continue all day and it was impossible to know where and when it would end. It felt like the end of the world – there was no way to grasp the nature of what was happening. When I returned to the roof and looked again, the World Trade Centre had gone completely, replaced by a vast black tower of smoke billowing into the blue.

Twenty-one months earlier, I had been in Los Angeles at the time of the Millennium. Somehow, everybody expected a transformation and a new era to begin then. Nobody wanted to admit it was a non-event. But that morning, I realised that I was witnessing the actual moment when one century ended and a different world was born.

For a couple of years, I had been working with producers in Times Sq who were to present a play of mine on Broadway, opening on September 15th 2001. I loved being in New York in those days, it was a true metropolis of glamour and affluence – a world incarnated in the now over-familiar fiction of “Sex & the City.” Many times I enjoyed Cosmopolitans at the Bowery Bar, the location where Candice Bushnell’s novel, which was the origin of that series, began.

Walking out onto the street on that September day, several miles from the unfolding catastrophe at the World Trade Centre, the scene was not dissimilar from usual, except – as people went about their business – I knew what everyone was thinking. We were all looking at each other in fear and knowing that we could only enact the semblance of routine. I went to the grocery story and bought food for the next few days. On my way back to the apartment, I saw a postcard of the World Trade Centre on a rack and, without thinking, I took the entire stack in hand, went into the store and paid for them.

Back at the apartment, I addressed postcards to everybody in my address book in England and then I went to the Post Office and mailed them all. I still do not understand why I did this, because I never wrote any messages on the cards, yet I knew everyone would realise who sent them and why. In fact, half arrived within ten days and half arrived four months later, intercepted perhaps as suspicious material in the collective paranoia that ensued.

On the first day J.F.Kennedy Airport reopened, I flew back to London, peering from the window of the jet at the smoke still rising from the foot of Manhattan. At once, I went to see my parents in Devon and found them well, but within a week my father died unexpectedly. My mother had dementia and could no longer live alone, so I chose to move back into the family house to care for her. My play never opened on Broadway and I did not have the American career that I so longed for at that time, but after the events I had witnessed it no longer mattered to me.

At KTS The Corner

Everyone in East London knows KTS The Corner, Tony O’Kane’s timber and DIY shop. With Tony’s ingenious wooden designs upon the fascia and the three-sided clock he designed over the door, this singular family business never fails catch the eye of anyone passing the corner of the Kingsland Rd and Englefield Rd in Dalston. In fact, KTS The Corner is such an established landmark that it is “a point of knowledge” for taxi drivers.

Yet, in spite of its fame, there is an enigma about KTS which can now be revealed for the first time. “People think it stands for Kingsland Timber Service,” said Tony with a glint in his eye, “Even my accountant thinks it does, but it doesn’t – it stands for three of my children, Katie, Toni and Sean.” And then he crossed his arms and tapped his foot upon the ground, chuckling to himself at this ingenious ruse. It was entirely characteristic of Tony’s irrepressible creative spirit which finds its expression in every aspect of this modest family concern, now among the last of the independent one-stop shops for small builders and people doing up their homes.

On the Kingsland Rd, Tony’s magnificent pavement display of brushes, mops and shovels, arrayed like soldiers on parade, guard the wonders that lie within. To enter, you walk underneath Tony’s unique three-sided clock – constructed to be seen from East, South and North – with his own illustrations of building materials replacing the numerals. Inside, there are two counters, one on either side, where Tony’s sons and daughters lean over to greet you, offering key cutting on your left and a phantasmagoric array of fixtures to your right. Step further, and the temporal theme becomes apparent, as I discovered when Tony took me on the tour. Each department has a different home made clock with items of stock replacing the numerals, whether nails and screws, electrical fittings, locks and keys, copper piping joints, or even paints upon a palette-shaped clock face. Whenever I expressed my approval, Tony grimaced shyly and gave a shrug, indicating that he was just amusing himself.

Rashly, Tony left his sons in charge while we retired to his cubicle office stacked with invoices and receipts where, over a cup of tea, he explained how he came to be there.

I’m from from Hoxton, I went to St Monica’s School in Hoxton Sq. To get me to concentrate on anything they had to tie me down, but, if anything physical needed doing, like moving tables and chairs, I’d be there doing it. My dad did his own decorating and my mother wanted everything completely changed every year or eighteen months, so he taught me how to hang wallpaper and to do lots of little jobs. After Cardinal Pole’s Secondary School, I did an apprenticeship in carpentry and got a City & Guilds distinction. Starting at fifteen, I did four years apprenticeship at Yeomans & Partners. Back then, when you came out of your apprenticeship, they made you redundant. You got the notice in your pay packet on the Thursday but on Saturday you’d get a letter advertising that they needed carpenters at the same company. They wanted you to work for them but without benefits and you had to pay a weekly holiday stamp.

I went self-employed from that moment. At the age of nineteen, I started my own company. I covered all the trades because I learnt that the first person to arrive on a building site is a carpenter and the last person to leave the site upon completion is a carpenter. Nine out of ten foremen are ex-carpenters and joiners, since the carpenter gets involved with every single other trade. So, over the years, I picked up plumbing, heating, electrics. When I started my company, I wouldn’t employ anyone if I couldn’t do their job – so I knew how much to pay ’em and whether they was doing it right or wrong.

This was in 1973, and Hackney Council offered me a grant to do up a building in Broadway Market. I just wanted an office, a workshop and a warehouse but they said you have to open a shop. So, as I was a building company, I opened a builders’ merchants and then, twenty years ago, I bought this place. When I bought it, it was just the corner, there was no shopfront. I designed the shopfront and found the old doors. I used to come here with my dad when we were doing the decorating for my mum, because they made pelmets to order here but, as a child, I never thought I’d own this place.

Tony is proud to assure you that he stocks more lines than those ubiquitous warehouse chains selling DIY materials, and he took me down into the vast cellar where entire aisles of neatly filed varieties of hammers and hundreds of near-identical light fixtures illustrated the innumerable byways of unlikely creativity. At the rear of the shop, through a narrow door, I discovered the carpentry workshop where resident carpenter Mike presides upon some handsome old mechanical saws in a lean-to shed stacked with timber. He will cut wood to any shape or dimension you require upon the old workbench here.

Tony’s witty designs upon the Englewood Rd side of the building are the most visible display of his creative abilities, in pictograms conveying Plumbing & Electrical, Joinery, Keys Cut, Gardening and Timber Cut-to-Size. When Tony took these down to overhaul them recently, it caused a stir in the national press. Thousands required reassurance that Tony’s designs would be reinstated exactly as before. It was an unexpected recognition of Tony’s talent and a powerful reminder of the secret romance we all harbour for traditional hardware shops.

Tony with his sons Jack and Sean.

A magnificent pavement display of brushes, mops and shovels.

The temporary removal of Tony’s wooden pictograms triggered a public outcry in the national press.

In the Kingsland Rd, you may also like to read about

The Map of Spitalfields Life

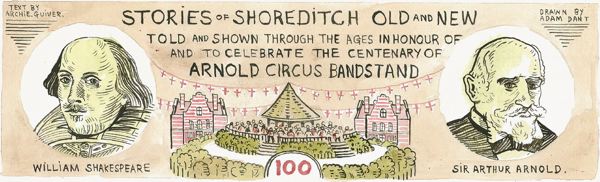

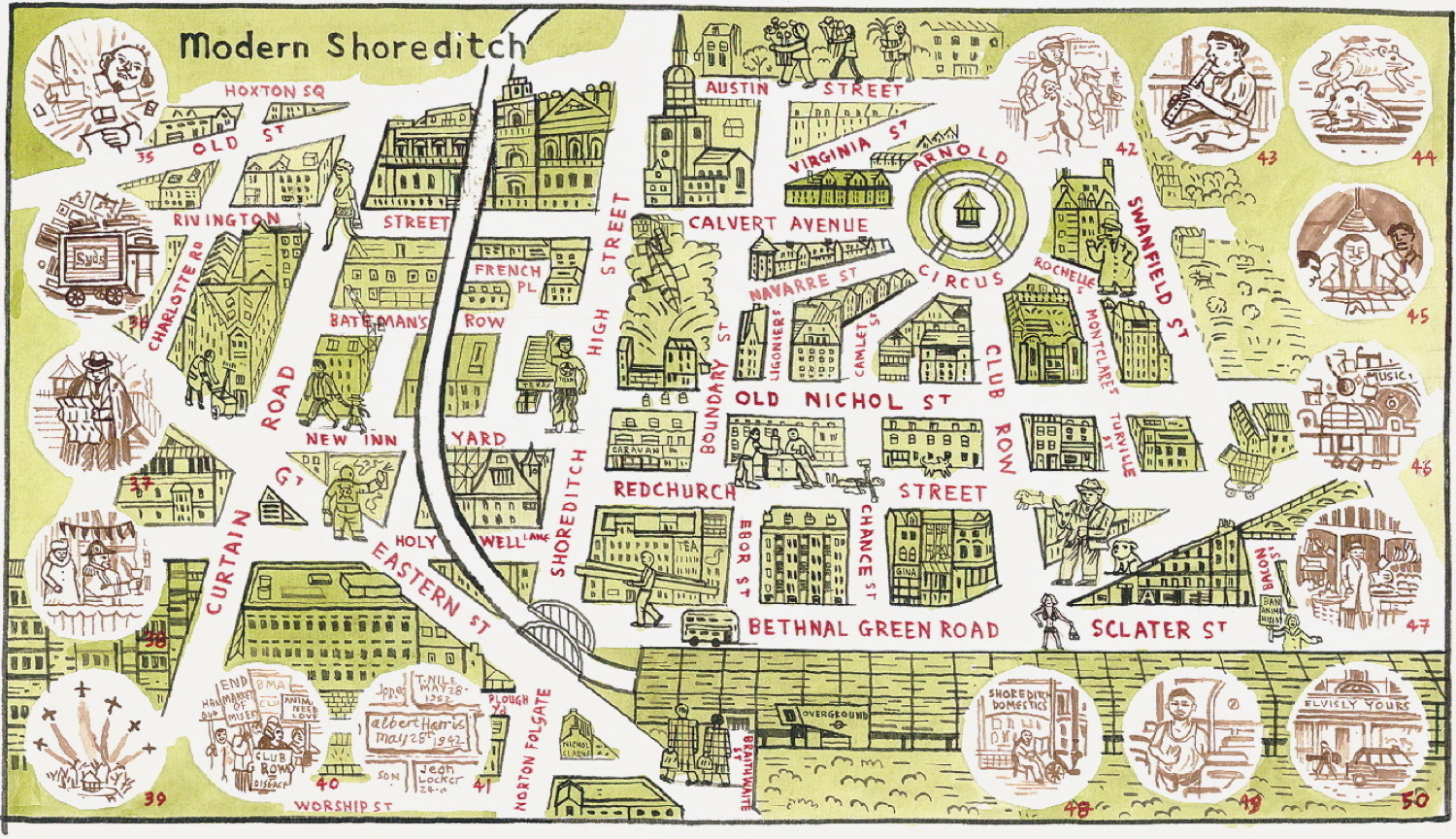

It is my pleasure to present the third exhibition from Spitalfields Life – Adam Dant, Unusual Cartography of East London at Town House, 5 Fournier St, Spitalfields, opening next Thursday 15th September and running until Sunday 2nd October.

At the rear of an eighteenth century weavers’ house is a beautifully proportioned doctor’s surgery of the eighteen twenties, where you are invited to come and scrutinise the jewel-like originals of Adam Dant’s wonderful and strange maps that it has been my privilege to publish over the past year – maps which have established Adam Dant as London’s pre-eminent mapmaker extraordinaire.

Most excitingly, the centrepiece of the exhibition is The Map of Spitalfields Life drawn by Adam Dant with stories by yours truly, showing fifty people who make Spitalfields distinctive. Please join us next Thursday for drinks from 7:30pm to view the map on the night of its unveiling to the people of Spitalfields by Sandra Esqulant, landlady of the Golden Heart in Commercial St. Many of the characters you have read about in these pages will be present to discover how Adam Dant has represented them on the map – so this is your chance to come and meet them.

The Map of Spitalfields Life will be published by Herb Lester and – once it has been unveiled – full-colour copies will be on sale at £4. On the reverse, you will find the stories of all the people portrayed on the front, plus a guide to Spitalfields landmarks and destinations. Adam Dant is also producing a hand-tinted limited edition for collectors and Spitalfields aficionados. Overseas and out-of-London readers will be relieved to know that, from 16th September, you will be able to buy these different versions of the map online at www.spitalfieldslife.com and have them delivered to your door.

Adam Dant and I have been burning the midnight oil to contrive The Map of Spitalfields Life for your delight and we can barely contain our excitement to show it to the world next week. The map has been produced under conditions of the strictest secrecy and, at this moment, Adam Dant and I alone know who is on the map. Today, I have been running around Spitalfields like the White Rabbit, delivering invitations to the unveiling. Yet although those who get an invitation are confirmed of their place on the map, they will not discover who else is on it until Sandra Esqulant unveils it. Already rumour, gossip and speculation about the map are spreading like wildfire through the narrow streets of Spitalfields, and we anticipate this conflagration to reach white heat by next Thursday. I do hope you will come to join the party.

Adam Dant says, “We hope this exhibition may assist the cartographic aesthetic to leap forward beyond the homogeneity of computerised rendering and the turgid angst of psycho- geography.”

The exhibition at the Town House, 5 Fournier St, London E1 6QE is open every day except Monday from 11:30am until 5:30pm, and at other times by contacting Town House.

Adam Dant tries vainly to hide The Map of Spitalfields Life from prying eyes.

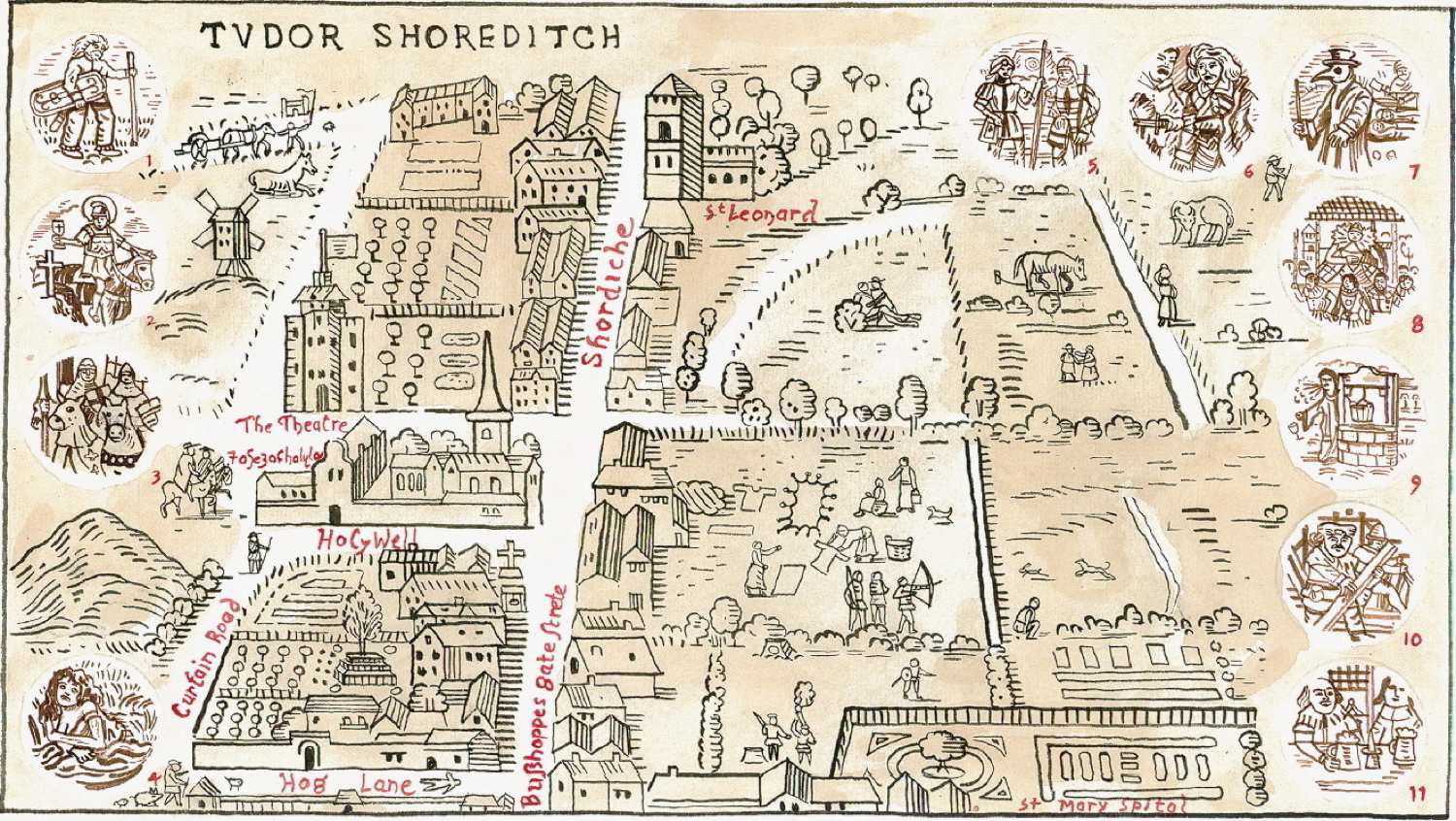

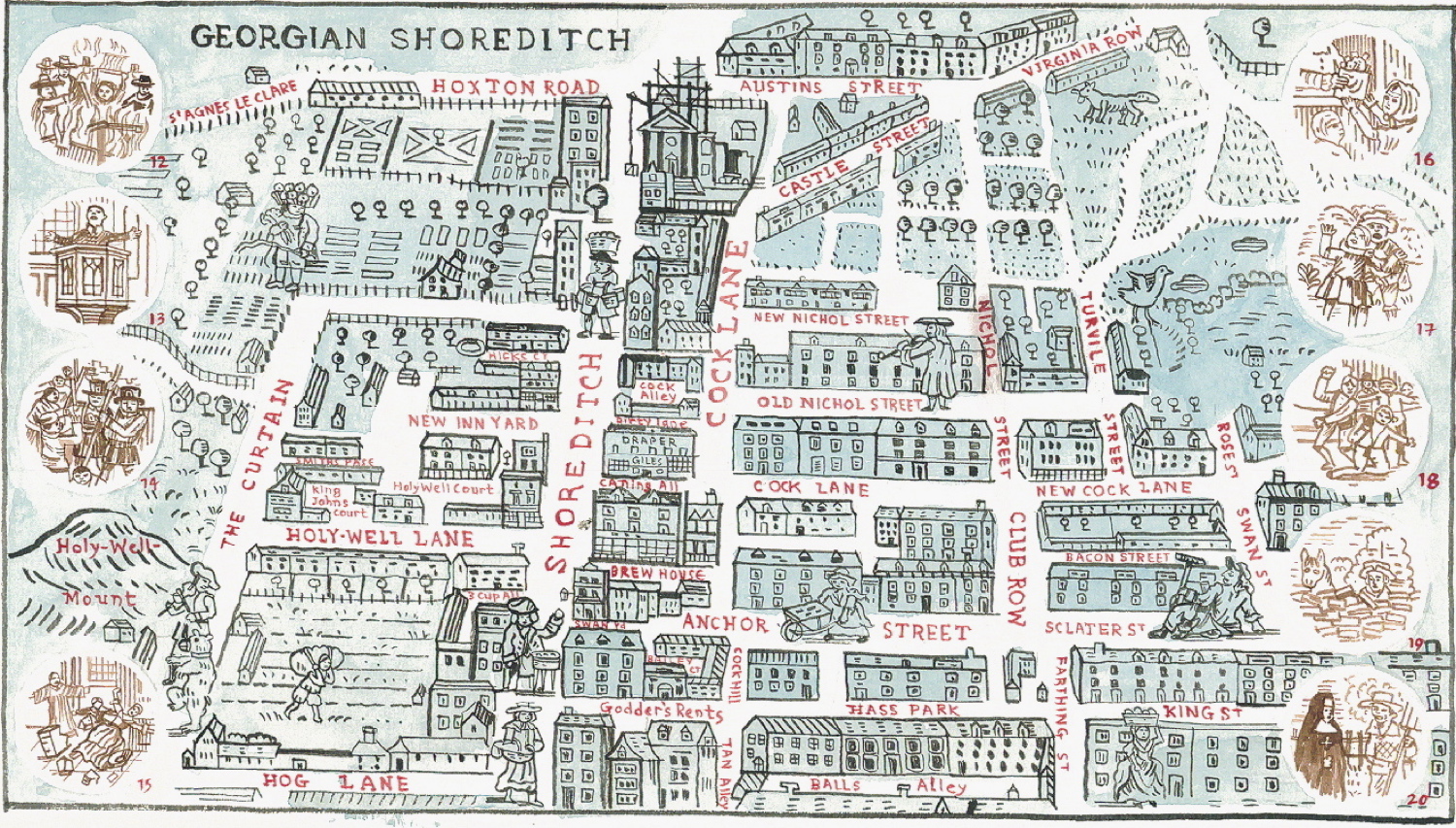

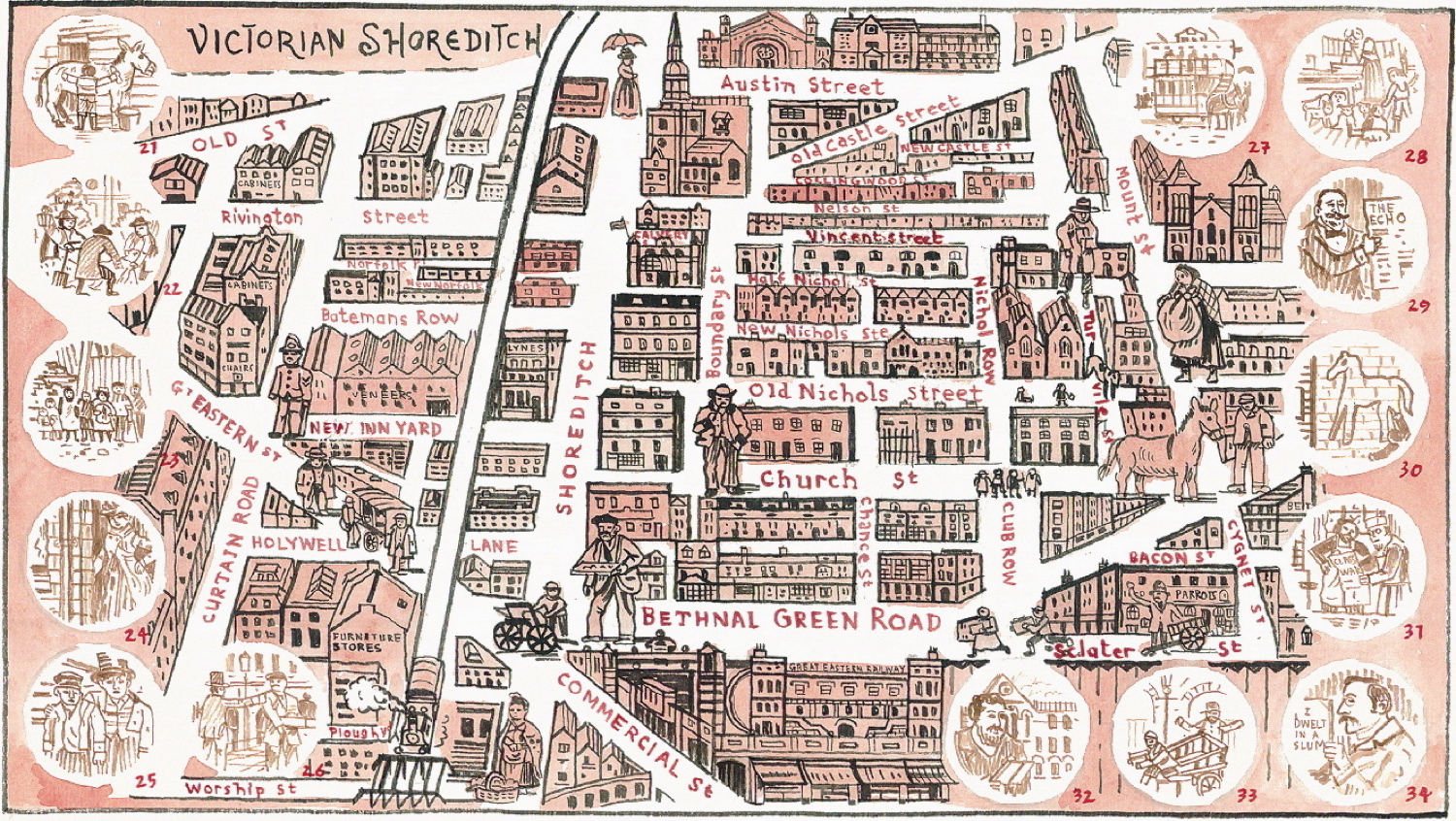

Map of the Stories of Shoreditch, Old & New.

Map of the Stories of Clerkenwell, Old & New.

The Map of Hoxton Square.

The Map of the Treasures of Hackney.

Donald Parsnips’ Plan of Shoreditch in Dream Format.

The Map of Shoreditch in the Year 3000.

The Map of Shoreditch as the Globe

Maps copyright © Adam Dant

You may like to take this moment to look back at some of Adam Dant’s Maps featured in the exhibition

Map of the History of Shoreditch

Map of Shoreditch in the Year 3000

Spitalfields Antiques Market 26

This sassy lady is Charlotte Sellers who grew up above a shop called “Junktique” that was run by her mother. “The shop was so small, rammed with chandeliers, glass and furniture etc that I was parked in my pram on the pavement outside.” she explained in fond reminiscence, “People would stop and ask inside the shop for the best price on the baby.” Charlotte’s father traded in military watches and important automobiles while her aunt traded in jewellery and coins. “It’s been in the family a long time, this second hand furniture business,” she informed me proudly, “I’m currently upholstering a bunch of chairs from the Battle of Waterloo.” But, whether Charlotte was referring to their origin in a pub of that name, or from the actual battleground, or merely the period of the seating in question, I never discovered.

This cheery fellow is Chris Williams. “I’ve only been back four months and I love every second of it,” he declared with aplomb, assuming a philosophical detachment from his own caprice, “I actually started in the market when I left school at sixteen in 1976, but I gave it up in 1986 thinking I could find better things in life to do.” After a career in transport, Chris is now like a lion let out of a cage. “I ran a courier company that I started in my bedroom and it went to twenty-five vans – then I sold it,” he confessed with a happy flourish. “I love looking for a bargain. I love selling things and meeting lots of different people, and in Spitalfields Market you meet lots of different people!”

These enigmatic women in black are Marcellina Amelia & Rebecca Dewinter who met while studying illustration at Westminster University and live in a big old warehouse in Bow, full of things they have collected. “This is how we make our money,” revealed Marcellina, with stark candour, gesturing to their stall, “because we are both artists.” Yet as well as their own personal artistic endeavours, Marcellina & Rebecca also contrive exotic jewellery and cleverly rework old clothes which you can see at Ivory Jar. “Sometimes we give stuff away too cheap because people beg us for things,” Marcellina whispered with a helpless grin, placing a hand protectively over a suitcase full of ducklings rendered in lifelike taxidermy,“We regret selling stuff we really like.”

This dignified figure is Roy Price who can be forgiven for looking a little fatigued because he just returned from Dorset, leaving at nine the previous evening to arrive back in London at one and then get up at six to come to the market. But Roy had no regrets. “I’ve done really well today,” he confided to me with a weary yet satisfied smile, “I’m so glad I came back.” Roy specialises in eighteenth century antiques. “I’ve traded from when I was eighteen because my dad did it and he used to sell this kind of stuff.” Roy said – assuring me even as his eyelids were drooping, “I do know what I’m doing and I’m knowledgeable.” Given Roy’s evident conscientious nature, I think we may conclude such warrants are unnecessary.

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman

Remembering Jean Rondeau the Huguenot

Marney & Ian MacDonald

This weekend the Huguenots returned to Spitalfields – three hundred years after they originally came from France and Belgium fleeing religious persecution and bringing flair and sophistication to the textile industry that was to occupy this corner of London for subsequent centuries. The occasion of this recent gathering was the dedication of a plaque to Jean Rondeau, Master Silk Weaver and Sexton of Christ Church from 1761-1790, honouring all those Huguenot families who passed through Spitalfields so long ago.

Here you see Marney MacDonald from Montreal being photographed in Christ Church by her husband Ian in front of the new plaque to her great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Jean Rondeau – or, as he is known in the family, John the Sexton, to distinguish him from his father Jean Rondeau who came here from Paris in 1685. Naturally, it was necessary have a record of the proud event, because it was the culmination of a long journey from the day Marney picked up on her father’s research into her great grandmother Phoebe Rondeau (Jean’s granddaughter), begun more than forty years ago.

Through a chance meeting in Christ Church when she visited as a tourist in 1999, Marney learnt of the study being undertaken of the human remains exhumed from the crypt and she met Stanley Rondeau, a voluntary tour guide who is a fellow descendant of Jean Rondeau. They pooled researches into their forbears, even going to the Natural History Museum where John the Sexton’s bones are now preserved to examine the remains of their common ancestor. And together they have been responsible for initiating this new memorial.

On Sunday, around thirty guests gathered on the North staircase in a location that would have been familiar to John the Sexton, while Andy Rider, Rector of Christ Church, undertook the dedication of the plaque and, although for the most part these people did not know each other, there was the affectionate intimate atmosphere of a family gathering in which no-one was a stranger to another. And in spite of the tenuous nature of the threads stretching across long periods of time which connect these people, there were visible shared qualities of visage, physique and colouration. “Being involved in finding ones antecedents is a fascinating process,” Marney confided to me in a quiet moment, speaking of a project that has occupied her for decades, “Something old in Canada might be two hundred years old but things here go back much further.”

Yet even though we were in the building that John the Sexton knew, he did seem very far away – until I joined the guests for a cup of tea afterwards and was introduced to so many of his relatives, especially seven week old Cassandra Stanley, his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter. Peacefully sleeping through the event, she was summoning her energies for a whole life ahead. Among the speeches and announcements, including a letter of greetings from the Queen, was an apology for absence from ninety-two year old Lynn Rondeau who wished it to be known that she was “proud to be a Rondeau.”

Marney showed me the album she has collected with copies of the documents relating to John the Sexton, an extraordinary paper trail which constitutes the evidence of her ancestor’s life – his name on the petition to parliament for Christ Church to be built, silk designs made for him by Anna Maria Garthwaite, his will and even the collection to raise a fund for his widow Margaret. The book is the result of detective work on Marney’s part. “How I wish I had the forethought to ask certain questions of my grandfather, that it has taken me a lifetime to answer.” she admitted in good humoured resignation as she closed the book.

Jean Rondeau was one of between twenty and twenty-five thousand Huguenots who came to Spitalfields, around half of the total of all those who came to make new lives in Britain. Although his story is documented and his descendants have traced the lineage, establishing the Rondeaus as one of Spitalfields’ oldest families, equally there exists all those other families that will never be traced and whose stories have faded forever into the ether. Yet the story of Jean Rondeau reminds us of the direct connection we share to forebears known and unknown, and of the common bonds of humanity that unite us all.

The Rondeaus gather in Christ Church where their ancestor was Sexton two hundred and fifty years ago.

Just seven weeks old, Cassandra Stanley (held by her great aunt Beryl Happe) is the youngest descendant of Jean Rondeau the Huguenot, her great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather who came to Spitalfields in 1685.

Stanley Rondeau

If you visit Christ Church on a Tuesday, when Stanley works there as a guide, he will show you the album collected by Marney MacDonald with all the documents and information about their common ancestor.

You may like to read my other stories about Stanley Rondeau

At Walton on the Naze

All this time, Walton on the Naze has been awaiting me, nestling like a forgotten jewel cast up on the Essex coast, and less than an hour and a half from Liverpool St Station.

Families with buckets and spades joined the train at every stop, as we made our way eastwards to the point where Essex crumbles into the North Sea at the rate of two metres a year. Yet all this erosion, while reminding us of the force of the mighty elements, also delivers a perfect sandy beach – the colour of Cheddar cheese – that is ideal for sand castles and digging. Stepping from the small train amongst the flurry of pushchairs and picnic bags, at once the sea air transports you and the hazy resort atmosphere enfolds you. Unable to contain yourself, you hurry through the sparse streets of peeling nineteenth century villas and shabby weather-boarded cottages to arrive at a rise overlooking Britain’s third longest pier, begun in 1830.

In spite of the majestic pier, this is a seaside resort on a domestic scale. You will not find any foreign tourists here because Walton on the Naze is a closely guarded secret, it is kept by the good people of Essex for their sole use. At Walton on the Naze everyone is local. You see Essex families running around as if they owned the place, playing upon the beach in flagrant carefree abandon, as if it were their own back yard – which, in a sense, it is.

This sense of ownership is manifest in the culture of the beach huts that line the seafront, layers deep, in higgledy-piggledy terraces receding from the shore. These little wooden sheds are ideal for everyone to indulge their play house and dolls’ house fantasies – painting them in fanciful colours, giving them names like “Ava Rest,” and furnishing the interiors with gas cookers and garish curtains. At the seaside, all are licenced to pursue the fulfilment of residual childhood yearning in harmless whimsy. The seaside offers a place charged with potent emotional memory that we can return to each Summer. It is not simply that people get nostalgic for seaside resorts, but that these seasonal towns become the location of nostalgia itself – because the sea never changes and we revisit our former selves when we come back to the beach.

Walton Pier curls to one side like a great tongue taking a greedy lick from an ocean of ice cream, and the beach curves away in a crooked smile that leads your eye to the “Naze,” or “nose” to give its modern spelling. This vast bulbous proboscis extends from the profile of Essex as if from a patient in need of plastic surgery, provided in the form of relentless abrasion from the sea.

With so many attractions, the first thing to do is to sit down at the tables upon the beach outside Sunray’s Kiosk which serves the best fish & chips in Walton on the Naze. Every single order is battered and cooked separately in this tiny establishment, that also sells paper flags for sandcastles and shrimping nets and all essential beach paraphernalia. From here a path leads past a long parade of beach huts permitting you the opportunity to spy upon these domestic theatres, each with their proud owners lounging outside while their children run back and forth, vacillating between their haven of security and the irresistible wonder of the waves crashing at the shoreline.

Here I joined some girls, excitedly fishing for crabs with hooks and lines off a small jetty. They all screamed when one pulled out a much larger specimen than the tiddlers they had in their buckets, only to be reassured by the woman who was overseeing their endeavour. “Don’t be frightened – it’s just the Mummy!” she declared with a wicked smile, as she held up the struggling creature by a claw. From this jetty, I could see the eighty foot tower built upon the Naze in 1720 as a marker for ships entering the port of Harwich and after a gentle climb up a cliff path, and a strenuous ascent up a spiral staircase, I reached the top. Like a fly perched upon the nose of Essex, I could look North across the estuary of the Orwell towards Suffolk on the far shore and South to the Thames estuary with Kent beyond – while inland I could see the maze of inlets, appealingly known as the Twizzle.

In the week that Summer broke up, I was blessed with one clear day of sunshine for my holiday. And I returned to the narrow streets of Spitalfields for another year with my skin flushed and buffeted by the elements – grateful to have experienced again the thrall of the shoreline, where the land runs out and the great ocean begins.

Sunray’s Kiosk on the beach, for the best fish & chips in Walton on the Naze.

“On this promontory is a new sea mark, erected by the Trinity-House men, and at the publick expence, being a round brick tower, near eighty foot high. The sea gains so much upon the land here, by the continual winds at S.W. that within the memory of some of the inhabitants there, they have lost above thirty acres of land in one place.” Daniel Defoe, 1722

You may like to read about the Gentle Author’s previous holidays

The Gentle Author Opens Tower Bridge

What better way could there possibly be to commence the third year of daily stories than to open Tower Bridge? Yet I could barely believe it was going to happen as I walked down through the City and up onto the bridge approach where tourists milled on the pavement.

None knew the secret I was carrying as, emboldened by privileged information, I waved to the men inside the control cabin and they ushered me swiftly inside. At once, I shook hands with Bridgemaster Eric Sutherns – tall and dignified in a peaked cap, he looked for all the world like the captain of a ship, and here, suspended above the water with the controls before us, it was as if were upon the bridge of a liner. The outlook was breathtaking, but there was no time to contemplate it as the Bridgemaster introduced me to Bridgedriver David Duffy who, in the few brief minutes remaining, was eager to induct me into my task.

In moments, the controls of the most famous bridge in the world were to be given into my hands. A single black knob, resembling a gearstick, drives the raising and the lifting of the bascules – as the halves of the bridge are known. Eyeballing me with his intense blue pupils, David explained quickly that I needed raise the bascules to between seventy-six and seventy-eight degrees, but once the bridge reached fifty degrees, I must press the button that changed the light on the bridge from red to green, indicating to the vessel that it was safe to proceed. Already, David had initiated the sequence of events that culminated in raising the bridge. Sirens were sounding, traffic lights were flashing, gates were descending upon the roadway as cars and vans drew to a halt, and wardens in fluorescent jackets were shepherding pedestrians back behind the barriers.

Keen to give a semblance that I was capable to undertake the task, I nodded confidently as the vital instructions passed through one ear and out the other. Somehow I had put myself at the centre of a train of events that were entirely alien to me, but as the challenge drew close, it was essential that I maintain the sham of competence. Yet the staff at Tower Bridge were one step ahead of me. “Check that the vessel is in sight,” instructed Bridgedriver David Duffy, preoccupied with the multiple television monitors showing activity on the bridge as the last tourists scurried out of sight. Sublimated entirely by the expertise of the master, I turned and peered down the river, expecting to see an unremarkable craft.

In an instant, the intensity of the event was amplified a thousand fold as I saw a tall ship, with three masts and lines of sailors standing upon the rigging, coming straight towards me. No longer was I living in my familiar world but inhabiting a vision. Inescapably, it was time to open the bridge. I turned back to David Duffy and Eric Sutherns, only to discover they were excited too, because even to these experienced bridgemen, this was a rare spectacle. In unison, they directed their gaze to the control lever and David placed my hand upon it, with a nod that only meant one thing. I looked up to the computer monitor, which showed that the linking bolts, that hold the bridge rigid when it is closed, had retracted, and then I pulled the lever slowly towards me. There are two speeds – creep and full speed. With the audacity of a beginner, I chose full speed, and two and a half thousand tons of steel moved into life.

I held on, as if it were to life itself, alternating my gaze between the rising bridge outside the cabin, the monitor where the counter clocked up the angle of incidence, and the tall ship bearing down upon me. At fifty degrees, I hit the button that gave the Captain clearance to enter the bridge and he reciprocated by a blast upon the hooter. Then the bridge was at seventy-seven degrees and it was time to halt and hold on. Now the ship was upon us, so close that I could no longer see its entirety but only the section passing by. Unexpectedly, from behind me came the sound of cheering and out of the corner of my eye I could glimpse flags waving, because this was ARC Gloria, the training ship of the Colombian Navy, and the bridge was full with excited Colombians come to show their national pride.

Even in the face of a morbid fantasy that I might release the bascules to crash down, sinking the vessel, causing massive casualties and triggering an international incident, I could not resist my awe at the wonder of the spectacle passing before my eyes. So tall that it only cleared the walkway above by a few metres – eighty-one cadets dressed in the red, yellow and blue of the Colombian flag were standing in formation upon the rigging of ARC Gloria, singing their anthem and waving for joy at this glorious moment of passing through Tower Bridge.

Once the ship passed, it was time to switch the light on the bridge back to red and close it again. But then, as soon as I had recovered my breath, it was already time to open the bridge for the return of Arc Gloria to complete its ceremonial passage before leaving to cross the Alantic Ocean. Consequently, I was able to open the bridge a second time and enjoy it without being in the grip of the terror that overwhelmed my debut. The bridge went up, the ship went through and then it was all over. David closed the blinds in the cabin and presented me with an intricate certificate as evidence of my achievement.

I followed him down a staircase within the bridge structure and into the engine room where oil hydraulic pumps have replaced the steam engines which ran here until 1976. We stepped through a door leading to a gantry in a vast dark cavern of diabolic industrial gloom, extending below water level, constructed within the base of the bridge. Here I understood that each half of the bridge is a seesaw with the counterbalance hidden from view inside the towers. “It’s a unique job,” admitted David, with proud reticence, as we paused here beside this mammoth iron construction weighted with four hundred tons of lead.

Visiting one of the four control cabins which is still fitted out with its original equipment, David explained that four were necessary in the days of the London fogs, before telephone and radio, when often the bridge drivers could often not even see across to the other side of the bridge. Today, ships book their openings a day in advance and Tower Bridge opens between eight hundred and a thousand times a year, but when it originally came into service in 1894, the bridge opened six thousand times a year, responding to signals from ships entering and leaving the busy Pool of London at any time of the day or night.

There is a superlatively idiosyncratic logic to this marvel of nineteenth century engineering, which apart from switching from steam power to oil hydraulics still runs exactly as it was built. David told me that the bearings which the bridge turns upon are original. David told me that the architect Sir Horace Jones intended Tower Bridge to look industrial, faced in red brick, but he died before completion and they altered his design to face it in stone, making it more Gothic to harmonise with the Tower of London. David told me that Hitler instructed the bomber pilots to avoid Tower Bridge, so that it could be retained as a landmark. David told me that elevators were installed so pedestrians could cross by the walkways above when the bridge was open, but they were closed in 1910 because of the prostitutes that solicited there. David told that the Bridgemasters used to live in the houses built over the suspension bridges and as we spoke a wedding was taking place in the Bridgemaster’s dining room.

We shook hands upon the bridge. “I bet you didn’t realise it was so easy to move two and a half thousand tons of steel?” David queried with a kindly smile, as we made our farewells before we went our separate ways through the crowds. It had been an emotional visit and I was staggered by this mighty masterpiece, but I returned home secure in the knowledge that now I have moved two and a half thousand tons of steel with the hand that writes these words, it should be a simple matter to craft a new story for you every day.

David Duffy, Bridgedriver, at the control panel of Tower Bridge.

The vast cavity down inside a pier of the bridge.

“It’s a unique job”

This control cabin retains its original equipment.

In the nineteenth century, unable to leave their posts, Bridgedrivers required the use of portable toilets.

In this diagram you can see the toothed quadrants used to move the bascules. A miscalculation in the size of these quadrants means that they stick out of the walls on the inner side of the towers and metal boxes were constructed upon the exterior to cover where the ends protrude.

ARC Gloria of the Colombian Navy, with eighty-one cadets on the rigging singing their anthem.

With grateful thanks to Eric Sutherns, Bridgemaster, and all the staff of Tower Bridge.