Colin O’Brien & His Leica Camera

Colin O’Brien is giving a lecture on his photography at the Leica Store, 27 Bruton Place, Mayfair, W1 on Wednesday 29th July 6pm. Afterwards, he will be signing copies of LONDON LIFE, his recent monograph which is newly published by Spitalfields Life Books, and we will be giving away fifty prints of Colin’s Clerkenwell car crash photograph. There are only a limited number of tickets available and they are free. Click here to book yours

“I am not entirely sure how I came to be the owner of my prized Leica Model 111a with an Elmar f3.5 lens manufactured in 1936. Rumour has it that an Irish chauffeur who lived in Victoria Dwellings found it on the back seat of the Rolls Royce he drove and conveniently forgot to mention it to his employer. He must have seen me with my old box camera and offered the Leica to my parents for a nominal sum. These sorts of deals with expensive merchandise being sold ‘off the back of a lorry’ were not uncommon.” – Colin O’Brien reveals how he obtained the Leica camera with which he took many of his famous photographs.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR COPY OF COLIN O’BRIEN’S LONDON LIFE

You may also like to read about

Visit The Old Naval College At Greenwich

As part of the HUGUENOT SUMMER festival you can visit the unseen spaces of the Old Naval College hosted by Curator, Will Palin, on Monday 20th July from 1:30-5pm. Click here for tickets

Water Gate at Greenwich

When Queen Mary commissioned Christopher Wren in 1694 to build the Royal Hospital for Seamen, offering sheltered housing to sailors who were invalid or retired, she instructed him to “build the Fabrick with Great Magnificence and Order” and there is no question his buildings at Greenwich fulfil this brief superlatively. Early on a summer morning, you may discover yourself the only visitor and stroll among these august structures as if they existed solely for your pleasure in savouring their ingenious geometry and dramatic spatial effects.

Since the fifteenth century, the Palace of Pleasaunce commanded the bend in the river here, where Henry VIII was born in 1491 and Elizabeth I in 1533. Yet Inigo Jones’ Queen’s House built for Anne of Denmark and the words ‘Carolus Rex’ upon the eastern extremity of the Admiral’s House, originally begun in 1660 as a palace for Charles I, are the only visible evidence today of this former royal residence abandoned at the time of the English Civil War.

It was Wren’s ingenuity to work with the existing buildings, sublimating them within the seamless unity of his own grandiose design by replicating the unfinished fragment of Charles’ palace to deliver magnificent symmetry, and enfolding Inigo Jones’ house within extended colonnades. The observant eye may also discern a dramatic overstatement of scale in architectural details that is characteristic of Nicholas Hawskmoor who was employed here as Wren’s Clerk of Works.

From 1705, the hospital for seamen provided modest, wood-lined cabins as a home-from-home for those who had spent their working lives at sea, reaching as many as two-thousand-seven-hundred residents at its peak in 1814, until superceded in 1869 by the Royal Naval College that left in 1995. Today the University of Greenwich and Trinity School of Music occupy these lofty halls but, in spite of its overly-demonstrative architecture, this has always been a working place inhabited by large numbers of people and the buildings suit their current purpose sympathetically .

The Painted Hall is the tour-de-force of this complex, guaranteed to deliver a euphoric experience even to the idle visitor. Here the Greenwich Pensioners in their blue uniforms ate their dinners until James Thornhill spent eighteen years painting the walls and ceiling with epic scenes in the classical style celebrating British sea power and it was deemed too grand for anything but special occasions. Yet down below, the home-made skittles alley brings you closer to the domestic lives of the former residents – who once enjoyed fierce after-dinner contests here using practice cannon balls as bowling balls.

Exterior of the Painted Hall

The Chapel

King William Court

King William Court

The Admiral’s House was originally built as a residence for Charles I. Abandoned in the Civil War, Queen Anne commissioned Wren to rehabilitate the unfinished palace as part of his design for the Royal Hospital for Seaman which opened in 1705

Inspired by the Elgin marbles, the elaborate pediment in Coade stone is a tribute to Lord Nelson

Exterior of the Painted Hall

Pump and mounting block in Queen Anne Court

The chapel was completed to Wren’s design in 1751 and redesigned by James ‘Athenian’ Stuart in 1781

Plasterwork by John Papworth

Queen Anne Court

In the Painted Hall

Begun in 1708, Sir James Thornhill’s murals in the Painted Hall took nineteen years to complete

Man with a flagon of beer from Henry VIII’s Greenwich Palace

Man with a flask of gin from Henry VIII’s Greenwich Palace

The Skittles Alley of the eighteen-sixties, where practice cannon balls serve as bowling balls

Entrance to the Old Royal Naval College

The Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich, is open daily 11:00 – 5:00 Admission Free

An Introduction To East End Garden History

As a prelude to her lecture on The Floral Traditions of Spitalfields given as part of the HUGUENOT SUMMER festival this Saturday July 18th at 2pm at Tower Hamlets Local History Library, Margaret Willes author of The Gardens of the British Working Class offers this introduction to the horticultural history of the East End. Click here for tickets

Early twentieth century garden at the rear of WF Arber & C0 Ltd, Printing Works

Today Spitalfields and Shoreditch are intensely urban areas but, four centuries ago, the scene was very different. Maps of this era show that behind the main roads flanked by houses and cottages, there were fields of cattle and, close by the city walls, laundrywomen laying out their washing to dry.

Many craftsmen who needed to be near to the City of London, yet who did not wish to be liable to its trading restrictions, found a home here. At the end of the sixteenth century, Huguenot silk weavers fleeing from religious persecution in the Spanish Netherlands and France, and landing at ports such as Yarmouth, Colchester and Sandwich, made their way to the capital. Records of this first wave of Huguenots and their arrival in Spitalfields are sparse, but there are references to them in the rural village of Hackney for instance.

Just as these ‘strangers’ took up residence east of London, so too did actors and their theatres. William Shakespeare lodged just within the City walls in Silver St, in the fifteen-nineties, in the home of an immigrant family from Picardie, the Mountjoys, who were involved in silk and wire-twisting.

Tradition tells us that these refugees brought with them their love of flowers. Bulbs and seeds may easily be transported, so they could have brought their floral treasures in their pockets. The term ‘florist’ first appears in English in 1623 when Sir Henry Wotton, scholar, diplomat and observer of gardens wrote about them to an acquaintance. He was not using ‘florist’ in its modern sense as a retailer of cut flowers, but rather as a description of an enthusiast who nurtured and exhibited pot-grown flowers such as tulips and carnations. One flower that has been traditionally associated with the Spitalfields silk weavers is the auricula, with its clear-cut colours. Auricalas do not like rain, so those who worked at home were in an ideal position to be able to bring them under cover when inclement weather threatened.

Another ‘outsider’ living in Spitalfields in the mid-seventeenth century was the radical apothecary, Nicholas Culpeper. He set up home in the precincts of the former Priory of St Mary Spital with his wife Alice Ford in 1640, probably choosing to be outside the City in order to able to practise without a licence. A Nonconformist in every sense, he disliked the elitism of the medical profession and in his writings threw down a challenge by offering help to all, however poor they were. He developed his knowledge by gathering wild flowers and herbs, but it is likely he also cultivated them in his own garden. His English Physitian, later known as the Complete Herbal, is one of the most successful books published in the English language and is still available today.

Culpeper’s books are a reminder that the garden has been for centuries the vital source of all medicines and poultices in this country. As London expanded, and private gardens within the City walls were built over, so the supply of medicinal herbs for apothecaries and housewives became of vital importance. Some of the market herbwomen are mentioned by name in the records of 1739-40 of the Fleet Market along with their places of residence. Hannah Smith, for example, came from Grub Sin in Finsbury, but others from further afield, such as Bethnal Green and Stepney Green. The remedies of the period required large quantities of certain herbs, such as wormwood and pennyroyal, and these women cultivated these as market gardeners.

With the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 by Louis XIV, a fresh wave of Huguenot refugees arrived, this time from France rather than the Lowlands. We know much more about these people, including their love of flowers, along with singing birds and linnets, which until quite recently could still be bought from Club Row Market. The French king made a mistake in divesting his realm of some of the most talented craftsmen: gunsmiths and silversmiths as well as silk weavers. The skill of the weavers was matched by their love of flowers in the exquisite silks they produced for court mantuas, the ornate dresses made for aristocratic ladies attending the court of St James. In these designs, a genuine attempt was made to produce botanical naturalism rather than purely conventional floral motifs and although today the most famous designer was Anna-Maria Garthwaite, there were others working alongside her in these streets.

As Spitalfields grew more developed in the eighteenth century, so the pressure on land increased and many of the gardens were built over with new houses. Some residents appear to have taken to their rooftops, creating gardens and building aviaries for their birds up there. Thomas Fairchild, who cultivated a famous nursery in Hoxton, recommended the kind of plants that could survive at this height, including currant trees. Others created gardens upon grounds along the Hackney and Mile End roads. A commissioner reporting on the conditions of the handloom weavers in the early nineteenth century described one such area, Saunderson’s Gardens in Bethnal Green.

“They may cover about six acres of ground. There is one general enclosure round the whole, and each separate garden is divided from the rest by small palings. The number of gardens was stated to be about one hundred and seventy: some are much larger than the rest. In almost every garden is a neat summer-house, where the weaver and his family may enjoy themselves on Sundays and holidays …. There are walks through the ground by which access is easy to the gardens.

The commissioner found that vegetables such as cabbages, lettuces and peas were cultivated, but pride of place was given to flowers. “There had been a contest for a silver medal amongst the tulip proprietors. There were many other flowers of a high order, and it was expected that in due time the show of dahlias for that season would not fail to bring glory to Spitalfields. In this neighbourhood are several dealers in dahlias.”

The competitions held for the finest florists’ flowers were fiercely fought. The Old Bailey sessions records include cases where thieves had broken into gardens not only to steal from the summer houses, but to take prize bulbs too. The Lord Mayor’s Day, 9th November, was traditionally the time to plant the bulbs and, in the spring, judges visited the gardens to make their decisions.

But these gardens were doomed, for the eastern parts of London – Bethnal Green, Stepney Green and Hackney – were being overwhelmed by street after street of new terraced houses. The handloom weavers of the area were likewise doomed, as the silk industry was threatened by competition from overseas and by looms powered by machinery in this country. Their love of flowers, however, was not to be dimmed, and a picture of a Spitalfields weaver in 1860 working alongside his daughters in a garret shows plants on the windowsill, while a contemporary account describes a fuchsia in pride of place near a loom, with its crimson pedants swinging to the motion of the treadles.

Root plants could be bought from sellers, especially along the Mile End Rd, and cut flowers from Spitalfields Market. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a market specifically for flowers and plants was established in Columbia Rd in Shoreditch. This followed the failure of an elaborate food market built by the philanthropist, Angela Burdett-Coutts in the nineteenth century. Her project had been based on a prospective railway line to deliver fish, which never materialised, while the traders preferred to sell outdoors and their customers, many of whom were Jewish immigrants, wanted to buy on Sunday. Originally, Columbia Market traded on Saturday but a parliamentary act moved it to Sunday, enabling Covent Garden and Spitalfields traders to sell their leftover stock, and this market flourishes still, attesting to the persistent love of flowers in the East End of London.

London Herb Woman, late sixteenth century from Samuel Pepys collection of Cries of London

Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654), the Spitalfields Herbalist

An auricula theatre

The tomb of Thomas Fairchild (1667-1729) the Hoxton gardener

Rue, Sage & Mint – a penny a bunch! Kendrew’s Cries of London

Buy my watercress, 1803

Buy my Ground Ivy, 1803

Chickweed seller of 1817 by John Thomas Smith

This is John Honeysuckle, the industrious gardener, with a myrtle in his hand, the produce of his garden. He is justly celebrated for his beautiful bowpots and nosegays, 1819

Here’s all a Blowing, Alive and Growing – Choice Shrubs and Plants, Alive and Growing, eighteen-twenties

Selling flowers on Columbia Rd in the nineteen seventies Photo by George Gladwell

Mick & Sylvia Grover, Herb Sellers in Columbia Rd – Portrait by Jeremy Freedman

Margaret Willes in her garden – Portrait by Sarah Ainslie

The Gardens of the British Working Class by Margaret Willes is published by Yale University Press

You may also like to read about

Nicholas Culpeper, Herbalist of Spitalfields

Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton

The Antiquarian Bookshops of Old London

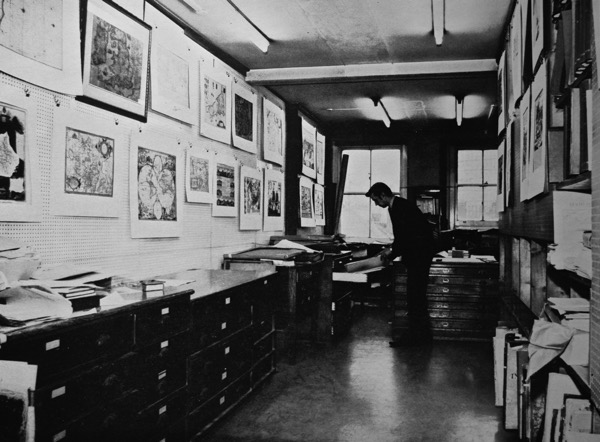

At Marks & Co, 84 Charing Cross Rd

When Mike Henbrey reminisced for me about his time working at Sawyer Antiquarian Booksellers in Grafton St and showed me these evocative photographs of London’s secondhand bookshops taken in 1971 by Richard Brown, it made me realise how much I miss them all now that they have mostly vanished from the streets.

After I left college and came to London, I rented a small windowless room in a basement off the Portobello Rd and I spent a lot of time trudging the streets. I believed the city was mine and I used to plan my walks of exploration around the capital by visiting all the old bookshops. They were such havens of peace from the clamour of the streets that I wished I could retreat from the world and move into one, setting up a hidden bedroom to sleep between the shelves and read all day in secret.

Frustrated by my pitiful lack of income, it was not long before I began carrying boxes of my textbooks to bookshops in the Charing Cross Rd and swapping them for a few banknotes that would give me a night at the theatre or some other treat. I recall the wrench of guilt when I first sold books off my shelves but I found I was more than compensated by the joy of the experiences that were granted to me in exchange.

Inevitably, I soon began acquiring more books that I discovered in these shops and, on occasion, making deals that gave me a little cash and a single volume from the shelves in return for a box of my own books. In this way, I obtained some early Hogarth Press titles and a first edition of To The Lighthouse with a sticker in the back revealing that it had been bought new at Shakespeare & Co in Paris. How I would like to have been there in 1927 to make that purchase myself.

Once, I opened a two volume copy of Tristram Shandy and realised it was an eighteenth century edition rebound in nineteenth century bindings, which accounted for the low price of eighteen pounds. Yet even this sum was beyond my means at the time. So I took the pair of volumes and concealed them at the back of the shelf hidden behind the other books and vowed to return.

More than six months later, I earned an advance for a piece of writing and – to my delight when I came back – I discovered the books were still there where I had hidden them. No question about the price was raised at the desk and I have those eighteenth century volumes of Tristram Shandy with me today. Copies of a favourite book, rendered more precious by the way I obtained them and now a souvenir of those dusty old secondhand bookshops that were once my landmarks to navigate around the city.

Frank Hollings of Cloth Fair, established 1892

E. Joseph of Charing Cross Rd, established 1885

Mr Maggs of Maggs Brothers of Berkeley Sq, established 1855

Marks & Co of Charing Cross Rd, established 1904

Harold T. Storey of Cecil Court, established 1928

Henry Sotheran of Sackville St, established 1760

Andrew Block of Barter St, established 1911

Louis W. Bondy of Little Russell St, established 1946

H.M. Fletcher, Cecil Court

Harold Mortlake, Cecil Court

Francis Edwards of Marylebone High St, founded 1855

Stanley Smith of Marchmont St, established 1935

Suckling & Co of Cecil Court, established 1889

Images from The London Bookshop, published by the Private Libraries Association, 1971

You might also like to read about

Mike Henbrey’s Collection Of Dividers

A few smaller examples from Mike Henbrey’s collection

Yesterday, I went back to visit Mike Henbrey and we photographed his collection of pairs of dividers. “Once every trade needed dividers to make measurements,” Mike informed me, “but when I worked in the secondhand tool shop nobody was interested to buy them.”

Yet this neglect became Mike’s gain and now the walls of his flat are lined with beautiful pairs of dividers of all kinds. As you can see from the two thousand-year-old Roman pair, the design has barely changed over time and Mike was the first to admit that some of the examples he describes as ‘nineteenth century’ could be two hundred years earlier.

Once you start to compare dividers, you eye becomes attuned to the subtleties of design – whether the knops are octagonal or round, the tiny design flourishes, the marks that indicate ownership and, above all, the elegant sculptural forms and proportions. As I handled them, I became aware of the weight and balance of each pair, all designed to sit comfortably in the hand.

It is impossible not to recognise an anthropomorphic quality and gender in the forms of dividers too. Curvaceous ones for measuring outside of things appear undeniably feminine while the straight pairs for measuring inside of things appear masculine. The matching nineteenth century interior and exterior measuring dividers illustrated below even have the proportion of a human couple standing side by side.

There is a sense of power when you wield dividers and, most of all, I thought of William Blake and his magnificent illustrations of Newton and the Ancient of Days. Several of the dividers in Mike’s collection resemble those in Blake’s paintings and are contemporary with him, so it was a small wonder to see dividers as Blake would have known them.

The Ancient of Days from ‘Europe – A Prophecy’ by William Blake

Pair of Roman dividers – two and a half inches tall

Late eighteenth/early nineteenth century pair with hexagonal knop – five inches tall

Twentieth century dividers by Thewlis & Griffith for interior and exterior measurement – six inches tall

Nineteenth century pair for measuring pipes or rods – twelve inches tall

One of Mike’s favourites, a tiny eighteenth century brass pair with steel pins and octagonal knop – one and a half inches

Blacksmith made – thirteen inches tall

Blacksmith made, this pair are marked with the initial ‘W’ on the handle – seven and a half inches tall

Large-scale nineteenth century dividers, large enough to measure beams or a ship’s mast

‘Very pleasing and functional heavy-duty, general purpose engineer’s dividers with notches to indicate ownership’ – thirteen inches tall

Large, early nineteenth century pair in brass and steel – eighteen inches – ‘I bought these for the lovely shape’

Unusual early twentieth century pair – possibly workshop made

Late eighteenth, early nineteenth century pair – ‘I bought these from a cello-maker’s workshop and they fit inside a cello’

Pair with decorative detail and wing-nut bolt – eleven inches tall

Cartographers’ dividers designed to be used with one hand – early twentieth century – eight inches tall

Nineteenth century pair with filed blade used for marking circles in wood – seven inches tall

Small nineteenth century pair with decoration and marked with initials ‘W H’ – seven inches tall

Unusual nineteenth century dividers for both inside and outside measurements – three and a half inches tall

Early twentieth century for engineering use – a wing nut on one side extends the dividers and a wing nut on the other side locks them – seven and a half inches tall

Very crude blacksmith made nineteenth century dividers – four inches tall

Five inch pair for measuring inside a tube – nineteenth century

Five and half inches tall with initials WH and wing nut

‘Nicely-detailed nineteenth century pair’ – six inches tall

The largest in Mike’s collection – eighteen inches tall and blacksmith made

A couple of ‘female’ and ‘male’ dividers by the same maker

A collection of tiny twentieth century dividers

William Blake’s Newton

In Mike Henbrey’s flat

You may also like to take a look at

Mike Henbrey, Collector of Books, Epherema & Tools

The Cockney Novelists

It is that time of year when you may be seeking some summer reading material and so today Contributing Writer Jonathon Green introduces the forgotten works of the Cockney Novelists

The ‘Cockney’ – that is the born East Ender – has long since been a regular figure in fiction. Originally, in appearances from Jacobean plays to mid-nineteenth century sporting fiction, the type was not working-class. It was the geography not the sociology that mattered. Wealthy merchants were still Cockneys and revelled in the name.

The East End of modernity, which (at least until recently) meant primarily poverty, is a mid-nineteenth century invention. Its citizens emerge, struggling and insecure, via the pages of Henry Mayhew’s pioneering sociological study, London Labour and the London Poor (1851). They are further investigated by Mayhew’s many successors, notably James Greenwood, but not until the nineteenth century was nearly over, were they fictionalised.

Dickens had portrayed Cockneys, but mainly as comic walk-on parts or, as in Oliver Twist, criminals who properly spoke cant. Other novelists, often temperance advocates whose ‘novels’ may as well have been tracts, looked East, but they made no attempt to put flesh on their caricatures. They were all in dreary earnest, propagandizing the proles, permitting neither smiles, jokes nor amusements, and certainly no drink or tobacco. For them, the East Ender was either debased or respectable, and the aim of their one-dimensional tales was to move him by whatever necessary means from the first to its sober antithesis.

What the historian P.J. Keating has labelled as the Cockney Novelists flourished towards the end of the nineteenth century and spilled over into the next. They included Arthur Morrison, Edwin Pugh, William Pett Ridge and – even if his bestseller purported to be reportage – Clarence Rook. While they dealt with their subject matter in different ways, all can be seen in at least one aspect of their work as combining a fictional form with a new concern with the London working classes, not as comedy cameos like Dickens or as objects about which one might preach and on whom one might prey, but as three-dimensional characters in their own right.

The first such writer was Henry Nevinson (1856-1941) a socialist, feminist and a campaigning journalist who in time covered the Boer War, Russia’s 1905 Revolution and – much against establishment wishes – the First World War (in which his son C.R.W. Nevinson was a war artist). In 1893, he was commissioned to write a series of sketches on working-class life. Following its author’s hands-on researches in the East End, where he had already run a mission and given classes in English literature, this appeared in 1895 under the title of Neighbours of Ours. There are a dozen stories, all narrated by the same Cockney speaker. What Nevinson offers is a portrait of a community, as realistic as he can make it, and without falling into stereotypes. He covers a variety of aspects, good and bad, and in Sissero’s Return even looks at a cross-race relationship. The book lay the groundwork for those who followed.

Arthur Morrison (1863–1945) began his professional life as a sports writer (boxing and bicycling) before moving on to fulltime work at The Globe in 1885. A year later, he became a clerk to the Beaumont Trustees, a charitable trust that administered the People’s Palace – a philanthropically designed educational and cultural centre for the local community – in Mile End. Here he began writing a series entitled Cockney Corners for the Palace’s magazine, the People’s Journal and it was these sketches that would lead him to further writings on the area. A short story, The Street was published by Macmillan’s in October 1891, followed by fourteen more tales of London’s most impoverished area, collected in book form in 1894 by W. E. Henley (who was already working with John Farmer on their slang dictionary) as Tales of Mean Streets. The book, with its unblinking depiction of East End squalor and the violence, crime and desperation that it engendered, was a controversial success, especially the story of Lizerunt (i.e. Liza Hunt), a young woman, once blithe and flirtatious, who is first beaten by her boyfriend and then forced by him into prostitution.

A Child of the Jago (1896) was even more controversial, with its exploration of life in an area known as The Jago (in reality the notorious Old Nichol slum off Bethnal Green Rd). This story of the street Arab Dicky Perrott laid out even more unmediated violence, criminality, dysfunctional family life and aggressive, fearful insularity. Drunkenness was a given. Despite the presence of a muscular Christian parson (Morrison’s portrait of the real-life Revd A. Osborne Jay, vicar of Holy Trinity, Shoreditch, and author of Life in Darkest London, 1891) Dicky cannot escape his environment and is murdered, refusing, as the Jago code demands, to ‘nark’ on his killer. In Morrison’s bleak portrait, death is the only escape the Jago will permit.

Henley, reviewing Child of the Jago, described it as ‘masterly’ but equally as ‘that terrible work.’ Against it he set another book, the popular journalist Richard Whiteing’s No 5. John Street, which he saw as ‘a fairy-tale [and] no mere debauch in sentiment, but— a refined and moving expression of reality.’ Richard Whiteing (1840–1928) was a foster child, apprenticed to a maker of seals and medals, and later attending art school at the Working Men’s College in Great Ormond St, where he met F.D. Maurice, John Ruskin and Frederick Furnivall, one of the pioneers of the OED. Furnivall’s ladies’ rowing eight, recruited from the New Oxford St ABC restaurant, featured in Whiteing’s novel Ring in the New (1906). His journalistic career began in 1866, on the Evening Star, where he wrote a column, supposedly in the persona of one Mr Sprouts, who rose to become an MP and embodied the principles of common sense and plain talk. The collected columns appeared as a book in 1867, but No 5 John Street was his best-seller. Somewhere between a sociological investigation and a Cockney novel, it followed the author as he lived in the East End slums in order ‘to learn what it is to live on half a crown a day, and to earn it.’

While Morrison may be seen as a descendant of Mayhew or Greenwood, a reformer’s zeal permeating his work. The remaining ‘Cockney’ writers are far more allied to Dickens, most of whose Cockneys were far from ‘savage’. For all that her home turf is The Cut, near Waterloo, no-one could epitomise the ‘chirpy cockney sparrer’ of popular myth more than the eponymous heroine of William Pett Ridge’s Mord Em’ly (1898). Mord is poor, her mother a nervous wreck and her father away (i.e. in prison) but if she runs in the streets as the junior member of the all-girl Gilliken Gang, there is no malice or hard-core criminality in her. Mord Em’ly is above all a feisty young woman, enjoying life, and giving as good, if not better than she gets. In her ‘happy ending’ Mord, now married, leaves for a new life in Australia. The book was a bestseller and a film appeared in 1922.

Edwin Pugh(1874–1930), whose titles include Tony Drum: A Cockney Boy (1898), Harry the Cockney (1912), and The Cockney at Home (1914), is the antithesis of Morrison. He allows for no irony and makes no attempt at the ultra-realism that his predecessor offers. Pugh is a sentimentalist and his affections veer unashamedly East. His own background – the son of a theatrical prop maker and a wardrobe mistress – may have been an influence. He sympathises with his characters’ problems, and they almost invariably have to battle (often unsuccessfully) against ill-fortune and tough lives, but there is no crime, no violence. His Cockneys are the ‘deserving’ poor – they are prey, not predators.

Clarence Rook (1862-1915), American but London-based and prolific in his time, remains something of a mystery, with one bestseller to his name, and a great deal of second-rate work to accompany it. George Bernard Shaw praised him as ‘very clever fellow’ but E.V. Lucas, another contemporary, saw him as one who ‘never fulfilled his many talents.’ A freelance journalist, Rook wrote the ‘By the Way’ column for The Globe, had a number of short stories published and in 1898 launched the career of one of fiction’s earliest female detectives – Miss Nora Van Snoop of the New York Detective Force

All of which was geared to a middle-class audience, but Hooligan Nights (1899) was very different, even though the readers again were doubtless middle-class, many of whom might have already read Morrison or Pugh. According to Rook, this was no novel but a piece of reportage based on ‘some sheets of manuscript’ shown to him by his publisher. ‘They contained certain confessions and revelations of a boy – named in the book as ‘Young Alf’ – ‘who professed to be a leader of Hooligans’. All else aside, Rook was using his journalistic instincts – the word hooligan, still of unknown origin, had only emerged – first recorded in police court reports – a year earlier. Such early uses were capitalised, suggesting a gang, but no evidence of this has survived. Rook claimed that Irish Court, in the same area, had once hosted an actual Patrick Hooligan who led the first such gang, and that Alf was ‘one on whom a portion at least of […] his mantle had fallen’ but he was touting an unproven etymology.

Young Alf, the star and supposed author of this Life and Opinions of a Young and Impenitent Criminal Set Down by Himself is a south Londoner and lives just down the road from Mord Em’ly, in the Elephant & Castle. Rook describes him as a ‘young man who walks to and fro in your midst, ready to pick your pocket, rifle your house or even bash you in a dark corner if it is made worth his while. […] It would, I think, be very difficult to persuade young Alf that honesty is the best policy.’ Alf is a professional, on however limited a scale, and since there is no moralising, he declares a frank delight in his occupation. He has, after all, a philosophy:

‘Look ’ere […] if you see a fing you want, you just go and take it wivout any ’anging abart. If you ’ang abart you draw suspicion and you get lagged for loiterin’ wiv intent to commit a felony or some damn nonsense like that. Go for it, strite. P’r’aps it’s a ’awse and cart you see as’ll do you fine. Jump up an’ drive away as ’ard as you can and ten to one nobody’ll say anyfink. They’ll think it’s your own prop’ty. But ’ang around and you mit jest as well walk into the next cop you see and arst ’im to ’and you your stretch. See? You got to look after yourself; and it ain’t your graft to look after anyone else, nor is it likely that anybody else’d look after you — only the cops. See?’

Nine years later, Rook published London Side-Lights, consisting of thirty brief sketches. In the twentieth, To Him Who Waits, we read again of Young Alf who has ‘gone away and laid his bones upon a battlefield – for he enlisted in a moment of enthusiasm – and his colonel announced that he had died as a good soldier.’

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Learn more about the Cockney Novelists in Jonathon Green’s history of slang Language! 500 Years of the Vulgar Tongue

You may also like to read about

Dicky Lumskull’s Ramble Through London

Courtesy of Mike Henbrey, it is my pleasure to publish this three-hundred-year-old ballad of the London streets and the trades you might expect to find in each of them, as printed and published by J. Pitts, Wholesale Toy & Marble Warehouse, 6 Great St Andrew Street, Seven Dials

![]()

Copyright © Mike Henbrey Collection

GLOSSARY

by Spitalfields Life Contributing Slang Lexicographer Jonathon Green

You may also like to read about