London Salt-Glazed Stoneware

As one who thought nobody else shared my passion for old salt-glazed stoneware, I was overjoyed when Philip Mernick granted me the opportunity to photograph these fine examples from his vast and historically-comprehensive collection which is greatly superior to my modest assembly.

In London, John Dwight of Fulham ascertained the method of the salt glaze process for rendering earthenware impermeable in 1671, thus breaking the German monopoly on Bellarmine jugs. Yet it was Henry Doulton in the nineteenth century who exploited the process on an industrial scale in Lambeth, especially in the profitable fields of bottle-making and drainpipes, before starting the manufacture of art pottery in 1870.

It is the utilitarian quality of this distinctive London pottery that appeals to me, lending itself to a popular style of decoration which approaches urban folk art. “I like it for its look,” Philip Mernick admitted , “but because nothing is marked until the late nineteenth century, it’s the mystery that appeals to me – trying to piece together who made what and when.”

Jug by Vauxhall Pottery 1810

Blacking bottles – Everett 1910 & Warren 1830 (where Dickens worked as a boy)

Gin Flagon, Fulham Pottery c. 1840

Spirit Flask in the shape of a boot by Deptford Stone Pottery c. 1840

Spirit flask in the shape of a pistol by Stephen Green and in the shape of a powder flask by Thomas Smith of Lambeth Pottery c. 1840

Reform flasks – Wiliam IV Reform flask by Doulton & Watts, eighteen- thirties, and Mrs Caudle flask by Brayne of Lambeth, eighteen-forties

Spirit flask of John Burns, Docks Union Leader, Doulton Pottery 1910

Nelson jug by Doulton & Watts 1830

Duke of Wellington jug by Stephen Green of Lambeth Pottery 1830

Mortlake Pottery Tankard, seventeen-nineties

Old Tom figure upon a Fulham Pottery Tankard c. 1830

Silenus jug by Stephen Green of Lambeth Pottery c. 1840

Victoria & Albert jug by Stephen Green of Lambeth Pottery 1840

Stag hunt jug by Doulton & Watts c. 1840

Mortlake Pottery jug, seventeen-nineties

Doulton jug hallmarked 1882

Jug by Thomas Smith of Lambeth Pottery 1840

Fulham Pottery jug c. 1830

Stiff Pottery jug c. 1850

Mortlake Pottery jug 1812

Figure of Toby Philpot on Mortlake jug

Deptford Pottery jug 1860

Stiff Pottery jug, with seller’s name in Limehouse 1860

Vauxhall Pottery jug with image of the pavilion at Vauxhall Gardens and believed to have been used there in the eighteen-thirties

Tobacco jug by Doulton & Watts, eighteen-forties

You may also like to read my earlier article

Dragan Novaković’s Brick Lane

These Brick Lane photographs from the late seventies by Dragan Novaković are published for the first time here today. Dragan came to London from Belgrade in 1968 and returned home in 1977, working for the state news agency Tanjug and then Reuters before his retirement in 2011.

‘I printed very rarely and very little, and for the next forty-odd years had these photographs only as contact sheets.’ explains Dragan, ‘I saw them properly as ‘enlargements’ for the first time in 2012, after I had scanned the negatives and post-processed the files.’

“I was introduced to London’s street markets by my friend and fellow countryman Mario who had a stall in Portobello Market specializing in post office clocks and bric-a-brac. I enjoyed sitting there with him amid the hustle and bustle, with people stopping by for a chat or to strike a bargain.

One early winter morning Mario picked me up in his old mini van and told me we were going to Bermondsey Market in search of clocks. It was still dark and foggy when we arrived and what met my eye made me gaze around in wonder – the scene looked to me as something out of Dickens!

The second time we went looking for clocks Mario took me to Brick Lane. Though there were plenty of open-air markets where I came from, I had seen nothing of the kind and size of Brick Lane and was fascinated by the crowds, the street musicians, the wares, the whole atmosphere. I sensed a strong community spirit and togetherness. I was hooked and I knew that I would have to come again in my spare time and take pictures.

Over the years I visited Brick Lane and other East End markets whenever I could spare the time and afford a few rolls of film. Living first in Earl’s Court and then behind Olympia, I would mount my old bicycle, bought in Brick Lane (of course!), and pedal hard across the West End in order to be there where life overflowed with activity.

I took what I consider snapshots without any plan or project in mind but simply because the challenge was too strong and I could not help it. I developed the films and made contact prints regularly but, never having a proper darkroom, made no enlargements to help me evaluate properly what I had done. Now I wish I had taken many more pictures at these locations.” – Dragan Novaković

Photographs copyright © Dragan Novaković

You also might like to take a look at

Majer Bogdanski, Tailor, Bundist, Yiddishist, Composer & Singer

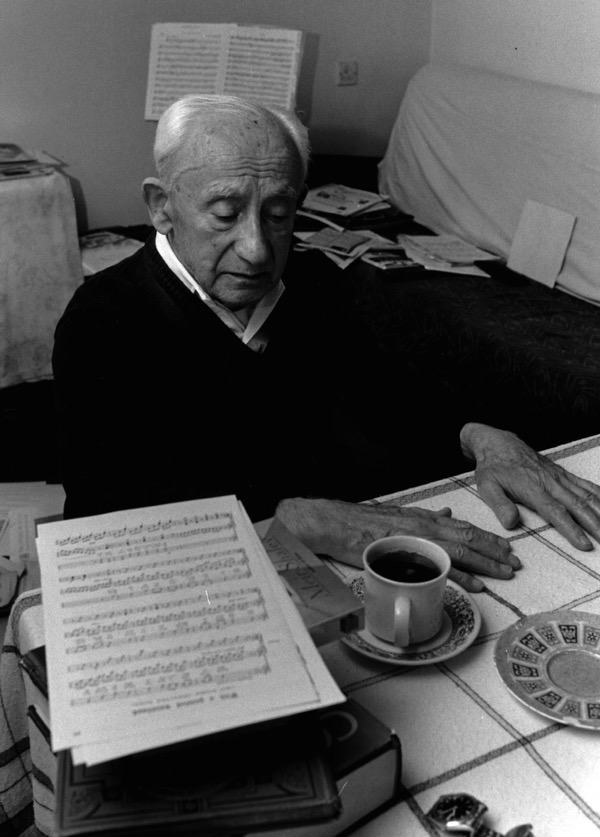

In the first of an occasional series, Photographer Sam Tanner introduces his portraits of Majer Bogdanski from his archive recording the Jewish community at the end of the last century

Majer Bogdanski

“These pictures were taken as part of my photography of the Jewish community in the East End between 1998 – 1999. When you carry out a long-term documentary project you always meet people with interesting stories and there are usually one or two who stand out. Majer Bogdanski was the most complex and vivid person I met. I photographed him at the Jewish Care Day Centre, The Friends of Yiddish at Toynbee Hall, his home and in the synagogue.

Born in 1912 in Pyotrkow-Tybunalski, Majer was a tailor in pre-war Poland and he confessed to me he was very poor. In the Polish army from 1939, he was captured by the Russians and sent to the Gulags. Majer described being unloaded from a train in the middle of Siberia, north of Archangel. It was a frozen waste, where there were no buildings, but they managed to build a fire and, although he reported all of the group he was with survived Stalin’s slave labour camps, many did not. They simply froze to death.

Majer told me he usually went without food at least one day a week in pre-war Poland. Consequently, privation had made him tougher than many of the others and he was also able to use his skills as a tailor to obtain more food. When Russia was attacked by the Nazis, he was sent to fight with the Allies along with the other Polish prisoners, joining the British Army in Italy. Only later did Majer learn that his wife Esther and most of his family were killed in the Holocaust.

In 1946, after the war, Majer settled in the East End where he worked as a tailor and learnt to play the violin. However, his love, passion and driving force was his love of Yiddish, which he sang. I remember, when my exhibition opened at the Jewish Museum, Majer asked if he could sing a Yiddish song and it turned out to be a memorable event.

He did everything he could to encourage and inspire others to learn speak and sing Yiddish. It seemed to me that his attempt to rescue a language all but murdered by the Nazis was Majer’s life work.”

– Sam Tanner

Majer Bogdanski (1912-2005)

Photographs copyright © Sam Tanner

You may also like to take a look at

Vinegar Valentines For Tradesmen

This selection from the Mike Henbrey collection of mocking Valentines at Bishopsgate Institute illustrates the range of tradespeople singled out for hate mail in the Victorian era. Nowadays we despise, Traffic Wardens, Estate Agents, Bankers, Cowboy Builders and Dodgy Plumbers but in the nineteenth century, judging from this collection, Bricklayers, Piemen, Postmen, Drunken Policemen and Cobblers were singled out for vitriol.

Bricklayer

Wood Carver

Drayman

Mason

Pieman

Tax Collector

Sailor

Bricklayer

Trunk Maker

Tailor

Omnibus Conductor

Puddler

Postman

Plumber

Soldier

Policeman

Pieman

Policeman

Cobbler

Railway Porter

House Painter

Haberdasher

Basket Maker

Baker

Housemaid

Guardsman

Chambermaid

Postman

Milliner

Carpenter

Cobbler

Images courtesy The Mike Henbrey Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

At The Royal Horticultural Society

If you crave the arrival of spring, I recommend a visit to one of my favourite events of the year, the Royal Horticultural Society Early Spring Plant Fair which runs until Wednesday

There may yet be another month before spring begins, but inside the Royal Horticutural Hall in Victoria it arrives with a vengeance today. The occasion is the Royal Horticultural Society Early Spring Plant Fair held each year at this time, which gives specialist nurseries the opportunity to display a prime selection of their spring-flowering varieties and introduce new hybrids to the gardening world.

No experience in London can compare with the excitement of joining the excited throng at opening time on the first day, entering the great hall where shafts of dazzling sunshine descend to illuminate the woodland displays placed strategically upon the north side to catch the light. Each one a miracle of horticultural perfection, as if sections of a garden have been transported from heaven to earth. Immaculate plant specimens jostle side by side in landscapes unsullied by any weed, every one in full bloom and arranged in an aesthetic approximation of nature, complete with a picturesque twisted old gate, a slate path and dead beech leaves arranged for pleasing effect.

Awestruck by rare snowdrops and exotic coloured primroses, passionate gardeners stand in wonder at the bounty and perfection of this temporary arcadia, and I am one of them. Let me confess, I am more of a winter gardener than of any other season because it touches my heart to witness those flowers that bloom in spite of the icy blast. I treasure these harbingers of the spring that dare to show their faces in the depths of winter and so I find myself among kindred spirits at the Royal Horticultural Hall each year.

Yet these flowers are not merely for display, each of the growers also has a stall where plants could be bought. Clearly an overwhelming emotional occasion for some, “It’s like being let loose in a sweet shop,” I overheard one horticulturalist exclaim as they struggled to retain self-control, “but I’m not gong to buy anything until I have seen everything.” Before long, crowds gather at each stall, inducing first-day-of-the-sales-like excitement as aficionados pored over the new varieties, deliberating which to choose and how many to carry off. It would be too easy to get seduced by the singular merits of that striped blue primula without addressing the question of how it might harmonise with the yellow primroses at home.

For the nurserymen and women who nurtured these prized specimens in glasshouses and poly-tunnels through the long dark winter months, this is their moment of consummation. Double-gold-medal-winner Catherine Sanderson of ‘Cath’s Garden Plants’ was ecstatic – “The mild winter has meant this is the first year we have had all the colours of primulas on sale,” she assured me as I took her portrait with her proud rainbow display of perfect specimens.

As a child, I was fascinated by the Christmas Roses that flowered in my grandmother’s garden in this season and, as a consequence, Hellebores have remained a life-long favourite of mine. So I always carry off exotic additions to a growing collection which thrive in the shady conditions of my Spitalfields garden – most recently, Harvington Double White Speckled and Harvington Double White.

Unlike the English seasons, this annual event is a reliable fixture in the calendar and you can guarantee I shall be back at the Royal Horticultural Hall next year, secure in my expectation of a glorious excess of uplifting spring flowers irrespective of the weather.

Double-gold-medal-winner Catherine Sanderson of ‘Cath’s Garden Plants’

You may also like to read about

At Captain Cook’s House In Mile End Rd

Contributing Writer Gillian Tindall tells the story of Captain Cook’s house in Whitechapel, sacrificed for a car park in 1958, and makes a plea for its reconstruction as part of the history of the place

Captain Cook’s house, c.1936

Long before the East End acquired its reputation as London’s working-class quarter, it had a different character. Walk along the Mile End Rd today from Whitechapel and, even after so much has been demolished in the interests of supposed urban regeneration, you will spot surviving signs of grandeur. Trinity Green, the last remaining set of almshouses, is still intact, as are a few eighteenth century private houses further east, two with central porches and elaborate iron-work. There was once a particularly large and splendid one of the same kind on the south side of the road too, built by the rich widow of an East India Company director, but of that no trace remains.

By the second half of the eighteenth century the area was becoming built up, with the City of London spreading out – just as it does today – and the London Hospital already established, yet it was still a ‘nice’ area for comfortably-off people. It was also particularly convenient for those whose interests lay in ships, with the Thames wharfs not far off. A property developer with the evocative name of Ebenezer Mussell acquired a strip of land in the seventeen-sixties between Mile End Green, which already had some substantial houses along it, and Mutton Lane, which much later would become Jubilee St. He called his new terrace on the main road, Assembly Row, yet he took his time building it, using several different builders, so the houses were not all to the same design. In the usual way of the times, it was the builders who sold them off on long-term leases.

In 1764 a sixty-one year lease on the eight-roomed end house, near the one owned by the East India Company widow, was bought by a thirty-six year old called James Cook. He was a Yorkshire boy by birth, son of an agricultural labourer who had risen to become a farm foreman. The farmer’s wife taught the boy his letters and, realising how bright he was, arranged for him to go to a charity school. Later, when he was apprenticed to a shopkeeper, his master noticed the same thing and got him a place with a Quaker shipmaster in Whitby. After that, after a spell as an ordinary seaman and experience in a brief war with France, Cook’s career as a determined and visionary navigator began to unroll without a backward glance. He became well known to the Admiralty and members of the Royal Society.

He had been living in then-rural Shadwell, with his young wife Elizabeth and their first child, a son who had been born while he was away on a long, exploratory voyage round Newfoundland. But now he had acquired the grander Assembly Row house. Four years and three more children later he was preparing for the first of his great scientific journeys to the Pacific, accompanied by botanists and an astronomer. He insured the house for £250, his household goods for another £200, and the family’s clothing and silver for additional amounts. Given that in those times £50 a year was a sufficient family income for a modestly respectable lifestyle, with a servant, these sums suggest considerable comfort.

The British Empire did not exist then and the East India Company was – to quote a remark of the time – ‘a ramshackle company trading in tea and opium.’ Pursuing a cloud on the horizon further off than little-known Australia – as Cook did – was an act of curiosity. He did not expect to discover New Zealand. The Maoris he met there living on the shores of the North Island were themselves immigrants who had arrived only two or three hundred years before. After initial problems, Cook and they made friends.

The voyage Cook set out on in 1768 did not bring him back to his house in the Mile End Rd for three years. Then he was off again from 1772 to 1775, and again from 1776 to 1780. This last was the journey that carried him to an inglorious death off Hawaii, where he had – untypically – antagonised the local people. Elizabeth did not get news of his death until the following year. She inherited the house and its contents, and received a pension of £200 a year for life from the king. She was thirty-eight and had given birth to six children, three of whom had already perished. Her eldest boy, who was by then a teenage midshipman, was drowned in the same year his father died ended on the other side of the world. Both her other sons who survived birth also died young, one in a violent robbery and the other of a fever. Her only daughter also died. Deeply distressed by these repeated blows of fate, nevertheless she lived on to the age of ninety-three, apparently sustained by her Methodist belief. By then, Elizabeth had long since moved away from the Mile End Rd, which had become urban.

Later in the nineteenth century, when the grand inhabitants were forgotten, Cook’s house, along with the neighbouring ones, had a shop built out in front. In the early twentieth century, this became a women’s clothes shop – ‘Corsets made to measure a speciality’ – and later a kosher butcher. A London County Council blue plaque commemorating the fact that Captain Cook once lived there was put on the house in 1907, yet that did not protect it from demolition in 1958.

It was at the height of post-war architectural and historical destruction, when the Greater London Plan to demolish two-thirds of the Borough of Stepney was being implemented by planners possessing more simplistic political vision than any human feeling or common sense.

Egged on by ambitious architects and by well-intentioned ‘reformers,’ such as Father Joe Williamson of Whitechapel who seemed to think that Poverty & Sin could be wiped out by destroying the streets where it was currently in evidence, the local authority took high-handed decisions. None of the houses in the rest of the terrace were pulled down – they are still there now. The pretext for destroying Cook’s house appears to have been the supposed need to widen a narrow lane alongside it. In practice, the lane never got widened, its ancient cobbles remain to this day, leading merely to a puddled parking lot and the Seraphim & Cherubim Church. The pointless brick wall that has replaced the house was given a commemorative plaque in 1970, when the enlarged local authority of Tower Hamlets had acquired some notion of respect for the past – yet not sufficient to rebuild the house as it had been or to construct anything worthwhile in the empty space.

I will happily join forces with anyone who feels like campaigning for Cook’s house to be rebuilt. It will not matter if the interior is different from the original. What matters to me is to see the exterior reconstructed as it was, with the right twelve-paned windows, and the mutilated terrace restored. The inside could become ‘affordable’ flats or, even better, social housing. Why not?

Captain Cook’s house, c.1940

Wall constructed after demolition of Captain Cook’s house, 1968

Civic dignitaries unveil a plaque to Captain Cook in 1970

Elizabeth Cook (1742–1835) by William Henderson, 1830

Captain James Cook (1728-79) by Sir Nathaniel Dance-Holland, c. 1775

Captain James Cook’s signature

Captain James Cook’s signature

Archive images courtesy Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives

Gillian Tindall’s The Tunnel Through Time, A New Route For An Old Journey is out now as a Vintage paperback

You may like to read these other stories by Gillian Tindall

East End Vernacular In Bethnal Green

Salmon & Ball, Bethnal Green, by Albert Turpin c.1955

I am delighted to collaborate with V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green to present an event on Thursday 22nd February which explores the history of the Museum in encouraging artists in the East End.

When it first opened, the Museum displayed a magnificent gallery of grand master paintings which are now known as The Wallace Collection and, in the twenties, curator Arthur Sabin invited members of the Bethnal Green Working Men’s Art Club to display their own work there.

Archivist Gary Haines will talk about Arthur Sabin and his inspirational ideas, followed by a guided tour of the current painting collection at the Museum. Complementing this, I shall be giving an illustrated lecture about the artists who were encouraged by Sabin and showing the work of those who came after, selected from my book EAST END VERNACULAR, Artists who painted London’s East End streets in the 20th century.

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKETS

The Wallace Collection of paintings was hung in the Bethnal Green Museum when it first opened

Curator Arthur Sabin (far right) shows a dignitary around a show of paintings by members of the Bethnal Green Working Men’s Art Club at the Bethnal Green Museum in the twenties

“ARTHUR SABIN was Curator of the Bethnal Green Branch of the Victoria & Albert Museum from 1922 to 1940. Through his work, the Museum began the slow process of becoming the V & A Museum of Childhood, an undertaking that was completed by Sir Roy Strong in the seventies.

Sabin was inspired by the popular Children’s Room at the V & A South Kensington and, when he observed that the Bethnal Green Museum was full of bored children, decided to make it more child friendly. He rehung paintings at child’s eye level. He also set up a classroom and employed teachers, and started to collect items relating to childhood. Through this endeavour, he came to recognise the importance of the social and cultural history of childhood.

Sabin was convinced that Art could educate and improve the lives of those who saw it. In a speech he gave in 1931 to the Bethnal Green & Shoreditch Skilled Employment Committee on ‘The Relation of Museums to Skilled Employment,’ he described the role a museum should play.

‘An Art Museum, such as we have at Bethnal Green, is concerned with many phases of life, but more than anything else with the development of craftsmanship … Let us produce boys and girls who desire with all their hearts to do something – to make something – better than anyone else can do it or make it … The museums exist to encourage this tendency, to awaken this desire.’

Through the work of Sabin and those who followed, the V & A Museum of Childhood inspired countless generations of children by showing them Art & Design. I include myself, since I remember visiting as a child and staring up in awe at a suit of Japanese Samurai armour. The same armour is now on display at South Kensington but I am at eye level with it these days!”

Gary Haines, Archivist at V & A Museum of Childhood

St Paul’s School, Wapping 1997 by Dan Jones (Click on this image to enlarge)