Peter Bellerby, Globemaker

Once upon a time, Peter Bellerby of Bellerby & Co was unable find a proper globe to buy his father for an eightieth birthday present. Now Peter is to be found in his very own globe factory in Stoke Newington and hatching plans to set up another in New York – to meet the growing international demand for globes which he expects to exceed ten times his current outputs. A man with global ambitions, you might say.

Yet Peter is quietly spoken with deferential good manners and obviously commands great respect from his handful of employees, who also share his enthusiasm and delight in these strange metaphysical baubles which serve as pertinent reminders of our true insignificance in the grand scheme of things.

A concentrated hush prevailed as Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I ascended the old staircase in the former warehouse where we discovered the globemakers at work on the top floor, painstakingly glueing the long strips of paper in the shape of slices of orange peel (or gores as they are properly known) onto the the spheres and tinting them with fine paintbrushes to achieve an immaculate result.

“I get bored easily,” Peter confessed to me, revealing the true source of his compulsion, “But making globes is really the best job you can have, because you have to get into the zone and slow your mind down.”

“Back in the old days, they were incredibly good at making globes but that had been lost,” he continued, “I had nothing to go by.” Disappointed by the degradation of his chosen art over the last century, Peter revealed that, as globes became decorative features rather than functional objects, accuracy was lost – citing an example in which overlapping gores wiped out half of Iceland. “What’s the point of that?,” he queried rhetorically, rolling his eyes in weary disdain.

“People want something that will be with them for life,” he assured me, reaching out his arms around a huge globe as if he were going to embrace it but setting it spinning instead with a beautiful motion, that turned and turned seemingly of its own volition, thanks to the advanced technology of modern bearings.

Even more remarkable are his table-top globes which sit upon a ring with bearings set into it, these spin with a satisfying whirr that evokes the music of the spheres. Through successfully pursuing his unlikely inspiration, Peter Bellerby has established himself as the world leader in the manufacture of globes and brought a new industry to the East End serving a growing export market.

To demonstrate the strength of his plaster of paris casting – yet to my great alarm – Peter placed one on the floor and leapt upon it. Once I had peeled my fingers from my eyes and observed him, balancing there playfully, I thought, “This is a man that bestrides the globe.”

Isis Linguanotto, Globepainter

John Wright, Globemaker

Chloe Dalrymple, Globemaker

Peter Bellerby, on top of the globe

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Paul Bommer’s Salmagundy

Contributing Artist Paul Bommer, celebrated in Spitalfields for his plaque of Huguenot tiles on the Hanbury Hall, has produced this splendid limited edition of large letterpress cards on eclectic subjects in his characteristic graphic style. Click here to buy a set direct from Paul. In Spitalfields, sets are on sale at Townhouse and in Ledbury at Tinsmiths.

Signboards for taverns that existed in Bishopsgate in Shakespeare’s time

An automated oracle, both the Roman poet Virgil and the Medieval monk Friar Bacon had one

Cod Latin Tombs on the Appian Way

Trade card for Johannes van Oosterom’s Coffee-House

Croque Monsieur, a grilled ham and cheese sandwich, and Croque Madame, the same with an egg on top

Par le bois du Djinn où s’entasse de l’effroi/ Parle et bois du gin ou cent tasses de lait froid (By the woods of the Djinn, where fear abounds/ Talk and drink gin, or a hundred cups of cold milk). Alphonse Allais’ famous holorime in which both lines read the same.

In Bleak House, Miss Flite is a spinster caught up in the unending Jarndyce & Jarndyce lawsuit who keeps songbirds with names reflecting her initial hope and optimism and subsequent disillusionment and madness as the case drags on.

The Green Dragon, a traditional and once common British pub sign, indicating a connection to Wales

Mandragora, the medicinal root resembling a man which let out a fatal scream when dug up

Orion the Hunter with his belt is one of the most discernible constellations of the Winter sky

The Round Table with the Holy Grail, the sword Excalibur, and arms of King Arthur and his knights

Diepzee Schepselen (Deep Sea Creatures), marine beasts, after Adriaen Coenen’s Whale Book, 1585

Images copyright © Paul Bommer

You may also like to take a look at Paul’s other work

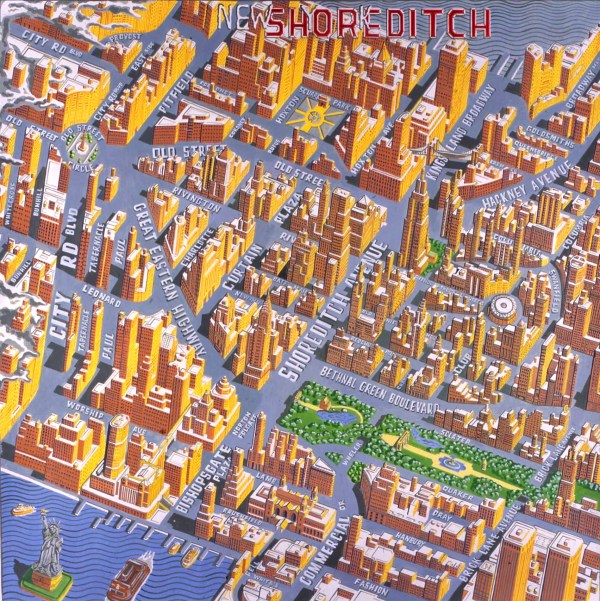

The Map Of Shoreditch As New York

Join me from six this Thursday 5th July for the East End launch party celebrating publication of Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND at The Townhouse, 5 Fournier St, E1. Adam’s exhibition in Spitalfields runs until 22nd July and his exhibition at The Map House in Knightsbridge continues until 14th July.

Click here to order a signed copy

(Click to enlarge)

When Adam Dant drew this map of Shoreditch as New York in the last century, he could not have been aware how prescient his vision might become. With a line of towers sprouting along Shoreditch High St and a host more in the pipeline, it may not be more than few years before the resemblance between this corner of the East End and Manhattan is more than a mere fancy.

“People sometimes say they like the New-Yorky feel, here in Shoreditch,” admitted Adam with a discernible twinkle in his eye, when I asked him how he came to draw this map of Shoreditch as New York. In his arresting conceit, Old St roundabout is transformed into Old St Circle, Arnold Circus Park becomes Madison Square Gardens and Liverpool St Station becomes Grand Central Station. The buildings and terminology are Americanised too, Brick Lane becomes Brick Lane Avenue, Bethnal Green Rd becomes Bethnal Green Boulevard and Quaker St becomes simply Quaker.

The comparison becomes less far fetched than you might assume, because Broadway in New York is along the line of an ancient pathway followed by the Algonquin tribe, whereas in Shoreditch, Old St follows the route of a primeval trackway of the ancient Britons, and Canal St in New York follows the route of the former canal whereas Shoreditch takes its name from the ‘suer’ that was once ditched and is now piped off. Both places are renowned for their mix of artists and immigrant culture, and down in Brushfield St, on the site of the Spitalfields Market, Adam has drawn New York’s Ellis Island building in acknowledgement of the immigrants who have come to New York and Spitalfields, defining the nature of these locations today.

Looking around the neighbourhood, you quickly come upon further clues. We have Rivington St just as they do, and Broadway Market and Columbia Rd too, chiming with New York. And the extension of the Great Eastern Railway up to Old St created a narrow triangular plot, occupied by a tall tapered building at the bottom of Great Eastern St which is reminiscent of the Flat Iron Building. Many people live in lofts in this vicinity today just as you might find in Soho or Tribeca. Here we have Shoreditch House whereas in New York they have Soho House.

One day, Adam & I were stopped in our tracks by an image on a passing truck in Redchurch St, showing New York viewed through Tower Bridge grafted onto the Brooklyn Bridge. But was it Tower Bridge joining the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River with Manhattan in the background? Or was it London with the New York Financial District transferred to Shad Thames? Was it London-as-New York or New York-as-London? We stood and looked at each other in amazement …

CLICK TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND BY ADAM DANT

Adam Dant’s MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND is a mighty monograph collecting together all your favourite works by Spitalfields Life‘s cartographer extraordinaire in a beautiful big hardback book.

Including a map of London riots, the locations of early coffee houses and a colourful depiction of slang through the centuries, Adam Dant’s vision of city life and our prevailing obsessions with money, power and the pursuit of pleasure may genuinely be described as ‘Hogarthian.’

Unparalleled in his draughtsmanship and inventiveness, Adam Dant explores the byways of English cultural history in his ingenious drawings, annotated with erudite commentary and offering hours of fascination for the curious.

The book includes an extensive interview with Adam Dant by The Gentle Author.

Adam Dant’s limited edition prints are available to purchase through TAG Fine Arts

William Oglethorpe, Cheese Maker

William Oglethorpe, Cheese Maker of Bermondsey

Everyone knows Cheddar, Stilton, Wensleydale and Caerphilly, but now there is an unexpected new location on the cheese map of Great Britain. It is Bermondsey and the man responsible is William Oglethorpe – seen here bearing his curd cutter as a proud symbol of his domain, like a medieval king wielding a mace of divine authority.

When photographer Tom Bunning & I went along to Kappacasein Dairy under the railway arches beneath the main line out of London Bridge in the early morning to investigate this astonishing phenomenon, we entered the humid warmth of the dairy in eager anticipation and encountered an expectant line of empty milk churns.

Already Bill had been awake since quarter to four. He had woken in Streatham then driven to Chiddingstone in Kent and collected six hundred litres of milk. Beyond us, in a separate room with a red floor and a large glass window sat a hundred-year-old copper vat containing that morning’s delivery of milk, which was still warm. Bill with his fellow cheesemakers Jem and Agustin, dressed all in white, worked purposefully in this chamber, officiating like priests over the holy process of conjuring cheese into existence. I stood mesmerised by the sight of the pale buttery liquid swirling against the gleaming copper as Bill employed his curd cutter, manoeuvring it through the milk as you might turn an oar in a river.

Taking a narrow flexible strip of metal, he wrapped a cloth around it so that the rest extended behind like a flag. Holding each end of the strip and grasping the corners of the cloth, Bill leaned over the vat plunging his arms deep down into the whey. When he lifted the cloth again, Agustin reached over with practised ease to take two corners of the cloth as Bill removed the sliver of metal and – hey presto! – they were holding a bundle of cheese, dredged from the mysterious depth of the vat. It was as spellbinding as any piece of magic I have ever seen.

“Cheesemaking is easy, it’s life that is hard,” Bill admitted to me with a disarming grin, when I joined the cheesemakers for their breakfast at a long table and he revealed the long journey he had travelled to arrive in Bermondsey. “I grew up in Zambia,” he explained, “And one day a Swiss missionary came to see my father and asked if I’d like to go to agricultural school in Switzerland.”

“I earned a certificate of competence,” he added proudly, assuring me with a wink, “I’m a qualified peasant.” Bill learnt to make cheese while working on a farm in Provence with a friend from agricultural college. “It was simply a way to sell all the milk from the goats, we made a cheese the same way the other farmers did,” he informed me, “We didn’t know what we were doing.”

Bill took me through to the next railway arch where his cheeses are stored while they mature for up to a year. He cast his eyes lovingly over the neat flat cylinders each impressed with word ‘Bermondsey’ on the side. Every Wednesday, the cheeses are attended to. According to their type, they are either washed or stroked, to spread the mould evenly, and they are all turned before being left to slumber in the chilly darkness for another week.

It was while working for Neals Yard Dairy that Bill decided to set up on his own as cheese maker. Today, Kappacasein is one of handful of newly-established dairies in London producing distinctive cheeses and bypassing the chain of mass production and supermarkets to distribute on their own terms and sell direct to customers. Yet Bill chooses to be self-deprecating in his explanation of why he is making cheese in London. “It’s just because I can’t buy a farm,” he claims, shrugging in enactment of his role of the peasant in exile, cast out from the rural into the urban environment.

“I’m interested in transformation,” Bill confided to me, turning serious as he reached his hand gently down into the vat and lifted up a handful of curds, squeezing out the whey. These would form the second cheese to come from the vat that morning, a ricotta. All across the surface, nodules of cheese were forming, coming into existence as if from primordial matter. “I don’t want to interfere,” Bill continued, thinking out loud and growing philosophical as he became absorbed in observing the cheese form, “Nature’s that much more complicated – if you let it do its own thing that’s much interesting to me than trying to impose anything. It’s about finding an equilibrium with Nature.”

Let me confess I had an ulterior motive for being there. A few weeks ago, I ate a slice of Bill’s Bermondsey cheese and became hooked. It was a flavour that was tangy and complex. One piece was not enough for me. Two pieces were not enough for me. Eventually, I had to seek the source of this wonder and there it was in front of me at last – the Holy Grail of London cheese in Bermondsey.

Cutting the curd

The curds

Squeezing the curds

Scooping out the cheese

The second batch of cheese from the whey is ricotta

Jem Kast, Cheese Maker

Ana Rojas, Yoghurt Maker

Agustin Cobo, Cheese Maker

The story of cheese

William Oglethorpe, Cheese Maker of Bermondsey

Photographs copyright © Tom Bunning

Visit KAPPACASEIN DAIRY, 1 Voyager Industrial Estate, Bermondsey, SE16 4RP

At Eastbury Manor

If you are seeking an afternoon’s excursion from the East End, you can do no better than visit Eastbury Manor in Barking, which is only half an hour on the District Line from Whitechapel yet transports you across four centuries to Elizabethan England.

Once Eastbury Manor stood in the centre of its own domain of rolling marshy farmland, extended as far as you can see from the top of its pair of octagonal turrets, but today it sits in the centre of a suburban estate built as Home for Heroes in the twenties in the pseudo-Elizabethan style, which casts a certain surreal atmosphere as you arrive. Yet by the time you have entered the gate and walked up the path lined with lavender to the entrance, the mellow brick facade of Eastbury Manor has cast its spell upon you.

Built in the fifteeen-sixties by Clement Sisley, Gentleman & Justice of the Peace, Eastbury Manor is among the earliest surviving Elizabethan houses, combining attractive domestic interior spaces with an exterior embellished by showy architectural elements in the renaissance manner. This curious contradiction of modest form and ambitious style speaks of Sisley’s eagerness to impress as a self-made property developer and landowner. He owned a house in the City of London and thus Eastbury grants us a vision of how those lost mansions that once lined Bishopsgate and Leadenhall St might have been.

Formerly part of the lands of Barking Abbey, after the Dissolution the property was sold to an absentee landlord before it was acquired by Clement Sisley in 1556. From apothecary bills, we know he fell ill and died in September 1578, bequeathing arms, weapons, armour and dags (guns) to his son Thomas ‘to him and his heirs forever at Eastbury’, in the hope that the manor might become a family home for generations to come.

Yet within only a few years Eastbury Manor was tenanted by John Moore, a Diplomat and Tax Collector, and his Spanish wife Maria Perez de Recalde. They were responsible for commissioning the lyrical and mysterious wall paintings, depicting an unknown European landscape rich in allegorical potential, glimpsed through a classical arcade of baroque barley-sugar-twist pillars.

Over two hundred years, the old house spiralled down through the ownership of a series of families with connection to the City of London until it became a farm, with animals housed in the fine Elizabethan chambers, and was threatened with demolition at the beginning of the last century.

Octavia Hill and C R Ashbee of the Survey of London, who had been responsible for saving Trinity Green Almshouses in Whitechapel, began a campaign to save Eastbury Manor by seeking guarantors to purchase the property from the owner. Once they had done so, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings arranged for the National Trust to accept ownership of the building in 1918. Thanks to the initiative of these enlightened individuals a century ago, we can enjoy Eastbury Manor today.

It is a sublime experience to escape the blinding sunlight of a summer’s afternoon and enter the cool air of the shadowy interior with its spiralling staircases and labyrinth of chambers. Ascend the turret to peer across Barking to the Thames, descend again enter the private enclosed yard at the rear, enfolded by tall ancient walls, and discover yourself in another world.

Eastbury Manor in 1796

Nonagenerian guide Dougie Muid welcomes visitors to Eastbury Manor – ‘Children often ask me if I have been here since the house was built’

Visit Eastbury Manor, Eastbury Square, Barking, Essex, IG11 9SN

You may also like to read about

The Caprice Of Mr Pussy

With your help, I am compiling a collection of stories of my old cat THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY, A Memoir Of A Favourite Cat to be published by Spitalfields Life Books on 20th September. Below you can read an excerpt.

I am delighted by the generous response from you, the readers – both in preorders and offers of financial support – but I am still need a few more who are willing to invest £1000 in THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY before I can send it to the printers. In return, I will publish your name in the book and invite you to a celebratory dinner hosted by yours truly. If you would like to know more, please drop me an email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

Alternatively, you can preorder a copy of THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY and you will receive a signed and inscribed copy in September when the book is published.

Click here to preorder your copy

If I am looking more bleary-eyed than usual these days, it is not because I am sitting up any later writing my stories, but because Mr Pussy insists on waking me at dawn at this season of the year. The first yowl usually wakes me from my slumber in the glimmering of daylight, yet if I should try to deny it, descending quickly back to my former depths of sleep, a louder, more insistent cry tells me that he will not be ignored.

If I should persist in feigning sleep, he will extend his claw and reach up to the bedside bookshelf to hook the copy of King Lear by the spine and tug it off in one stroke to crash down onto the floor – employing a particular choice of title that I have yet to understand fully.

Then I open my eyes momentarily in weary exasperation to face his pitiful expression of need, quelling my anger. The question rises in my mind, did I put out any food for Mr Pussy last night? Now, in my half-awake moment of emotional vulnerability, the seed of doubt is sown and sympathy aroused for Mr Pussy, pleading for his rations whilst I indulge my luxuriant ease. But I am capable of indifference to his pain, rolling over in bed to seek another forty winks – even though experience has taught me that Mr Pussy will respond by running up the covers and leaping on my back with the agility of a mountain goat, so that he may repeat his yowl directly into my ear.

Thus I have learnt not to roll over, instead – without opening my eyes – I extend a crooked forefinger in an attempt to pacify Mr Pussy through petting, stroking him beneath his chin and on his brow – provoking a loud and emotional purring and snakelike twisting of the neck. Making a sound like his engine is revving, Mr Pussy bares his teeth and rubs them up against my finger several times in glee, which causes him ecstatic delight and coats my finger in saliva. He may repeat this action several times with an accumulating sense of excitement, glorying in the moment, knowing now that it is only a matter of time before I recognise that it is simpler to bow to his will than to resist.

Submitting to Mr Pussy’s inexorable persuasion, I stumble to the kitchen and commonly discover plenty of food in his dish – revealing that I have been played, his ruse was an exercise in pure manipulation, a power game. Too weary to recognise the humiliation I have suffered, I climb back into bed, put King Lear back on the shelf and resume my slumber.

When I wake hours later, Mr Pussy is stretched out on the quilt, oblivious to me rising. Yet if I should wake him, he stretches out in pleasure. Mr Pussy has every reason to feel secure, because each night he tests me and confirms his control. Mr Pussy can relax in the knowledge that he is training me to become obedient to his will, and in my weakness I comply. I let him get away with murder.

CLICK HERE TO PREORDER A COPY OF THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY

Anyone that has a cat will recognise the truth of this memoir of a favourite cat by The Gentle Author.

“I was always disparaging of those who dote over their pets, as if this apparent sentimentality were an indicator of some character flaw. That changed when I bought a cat, just a couple of weeks after the death of my father. “

THE LIFE & TIMES OF MR PUSSY is a literary hymn to the intimate relationship between humans and animals, filled with sentiment without becoming sentimental.

George Parrin, Ice Cream Seller

Please keep your eyes open for my old friend George Parrin, the Ice Cream Seller, who is cycling around the East End now and, if you see George, stop him and buy one – and he will tell you his story.

‘I’ve been on a bike since I was two’

I first encountered Ice Cream Seller, George Parrin, coming through Whitechapel Market on his bicycle. Even before I met him, his cry of ‘Lovely ice cream, home made ice cream – stop me and buy one!’ announced his imminent arrival and then I saw his red and white umbrella bobbing through the crowd towards us. George told me that Whitechapel is the best place to sell ice cream in the East End and, observing the looks of delight spreading through the crowd, I witnessed the immediate evidence of this.

Such was the demand on that hot summer afternoon that George had to cycle off to get more supplies, so it was not possible for me to do an interview. Instead, we agreed to meet next day outside the Beigel Bakery on Brick Lane where trade was a little quieter. On arrival, George popped into the bakery and asked if they would like some ice cream and, once he had delivered a cup of vanilla ice, he emerged triumphant with a cup of tea and a salt beef beigel. ‘Fair exchange is no robbery!’ he declared with a hungry grin as he took a bite into his lunch.

“I first came down here with my dad when I was eight years old. He was a strongman and a fighter, known as ‘Kid Parry.’ Twice, he fought Bombardier Billy Wells, the man who struck the gong for Rank Films. Once he beat him and once he was beaten, but then he beat two others who beat Billy, so indirectly my father beat him.

In those days you needed to be an actor or entertainer if you were in the markets. My dad would tip a sack of sand in the floor and pour liquid carbolic soap all over it. Then he got a piece of rotten meat with flies all over it and dragged it through the sand. The flies would fly away and then he sold the sand by the bag as a fly repellent.

I was born in Hampstead, one of thirteen children. My mum worked all her life to keep us going. She was a market trader, selling all kinds of stuff, and she collected scrap metal, rags, woollens and women’s clothes in an old pram and sold it wholesale. My dad was to and fro with my mum, but he used to come and pick me up sometimes, and I worked with him. When I was nine, just before my dad died, we moved down to Queens Rd, Peckham.

I’ve been on a bike since I was two, and at three years old I had my own three-wheeler. I’ve always been on a bike. On my fifteenth birthday, I left school and started work. At first, I had a job for a couple of months delivering meat around Wandsworth by bicycle for Brushweilers the Butcher, but then I worked for Charles, Greengrocers of Belgravia delivering around Chelsea, and I delivered fruit and vegetables to the Beatles and Mick Jagger.

At sixteen years old, I started selling hot chestnuts outside Earls Court with Tony Calefano, known as ‘Tony Chestnuts.’ I lived in Wandsworth then, so I used to cycle over the river each day. I worked for him for four years and then I made my own chestnut can. In the summer, Tony used to sell ice cream and he was the one that got me into it.

I do enjoy it but it’s hard work. A ten litre tub of ice cream weighs 40lbs and I might carry eight tubs in hot weather plus the weight of the freezer and two batteries. I had thirteen ice cream barrows up the West End but it got so difficult with the police. They were having a purge, so they upset all my barrows and spoilt the ice cream. After that, Margaret Thatcher changed the law and street traders are now the responsibility of the council. The police here in Brick Lane are as sweet as a nut to me.

I bought a pair of crocodiles in the Club Row animal market once. They’re docile as long as you keep them in the water but when they’re out of it they feel vulnerable and they’re dangerous. I can’t remember what I did with mine when they got large. I sell watches sometimes. If anybody wants a watch, I can go and get it for them. In winter, I make jewellery with shells from the beach in Spain, matching earrings with ‘Hello’ and ‘Hola’ carved into them. I’m thinking of opening a pie and mash shop in Spain.

I am happy to give out ice creams to people who haven’t got any money and I only charge pensioners a pound. Whitechapel is best for me. I find the Asian people are very generous when it comes to spending money on their children, so I make a good living off them. They love me and I love them.”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

You might also like to read about

Matyas Selmeczi, Silhouette Artist