Maureen Rose, Button Maker

‘Every button tells a story’

On the ground floor of the house where Charles Dickens grew up at 22 Cleveland St in Fitzrovia is a wonderful button shop that might easily be found within the pages of a Dickens novel. Boxes of buttons line the walls from floor to ceiling, some more than a hundred years old, and at the centre sits Maureen Rose, presiding regally over her charges like the queen of the buttons.

“A very nice gentleman – well turned out – stood in my doorway and asked, ‘Charles Dickens doesn’t live here anymore, does he?'” Maureen admitted to me with a sly grin. “I said, ‘No, he doesn’t.’ And he said, ‘Would you have his forwarding address?’ So I said, ‘No, but should I get it, I’ll put a note in the window.'”

Taylor’s Buttons & Belts is the only independent button shop in the West End, where proprietor Maureen sits making buttons every day. It is a cabinet of wonders where buttons and haberdashery of a century ago may still be found. “These came with the shop,” explained Maureen proudly, displaying a handful of Edwardian oyster and sky blue crochetted silk buttons.

“Every button tells a story,” she informed me, casting her eyes affectionately around her exquisite trove. “I have no idea how many there are!” she declared, rolling her eyes dramatically and anticipating my next question. “I like those Italian buttons with cherries on them, they are my favourites,” she added as I stood speechless in wonder.

“Let me show you how it works,” she continued, swiftly cutting circles of satin, placing them in her button-making press with nimble fingers, adding tiny metal discs and then pressing the handle to compress the pieces, before lifting a perfect satin covered button with an expert flourish.

It was a great delight to sit at Maureen’s side as she worked, producing an apparently endless flow of beautiful cloth-covered buttons. Customers came and went, passers-by stopped in their tracks to peer in amazement through the open door, and Maureen told me her story.

“My late husband, Leon Rose, first involved me in this business. He bought it from the original Mr Taylor when it was in Brewer St. The business is over a hundred years old with only two owners in that time. It was founded by the original Mr Taylor and then there was Mr Taylor’s son, who retired in his late eighties when he sold it to my husband.

My husband was already in the button business, he started his career in a button factory learning how to make buttons. His uncle had a factory in Birmingham – it was an old family business – and he got in touch with Leon to say, ‘There’s a gentleman in town who is retiring and you should think about taking over his business.’

Leon inherited an elderly employee who did not like the fact that the business had been sold. She had been sitting making buttons for quite some time and she said she would like to retire. So at first my mother went in to help, when he needed someone for a couple of hours a day, and then – of course – there was me!

I was a war baby and my mother had a millinery business in Fulham. She was from Cannon St in Whitechapel and she opened her business at nineteen years old. She got married when she was twenty-one and she ran her business all through the war. As a child, I used to sit in the corner and watch her make hats. She used to say very regularly to me, ‘Watch me Maureen, otherwise one day you’ll be sorry.’ But I did not take up millinery. I did not have an interest in it and I regret that now. She was very talented and she could have taught me. She had done an apprenticeship and she knew how to make hats from scratch. She made all her own buckram shapes.

I helped her for while, I did a lot of buying for her from West End suppliers in Great Marlborough St where there were a lot of millinery wholesalers. It was huge then but today I do not think there is anything left. There was big fashion industry in the West End and it has all gone. It was beautiful. We used to deal with lovely couture houses like Hardy Amies and Norman Hartnell. I used to go to see their collections, it was glamorous.

I only make buttons to order, you send me the fabric – velvet, leather or whatever – and I will make you whatever you want. We used to do only small orders for tailors for suits, two fronts and eight cuff buttons. Nowadays I do them by the hundred. I do not think Leon ever believed that was possible.

Anybody can walk into my shop and order buttons. I also make buttons for theatre, television, film and fashion houses. I do a lot of bridal work. I am the only independent button shop in the West End. I get gentleman who buy expensive suits that come with cheap buttons and they arrive here to buy proper horn buttons to replace them.

My friends ask me why I have not retired, but I enjoy it. What would I do at home? I have seen what happens to my friends who have retired. They lose the plot. I meet nice people and it is interesting. I will keep going as long as I can and I would like my son Mark to take it over. He is in IT but this is much more interesting. People only come to me to buy buttons for something nice, although I rarely get to see the whole garment.

I had a customer who was getting married and she loved Pooh bear. She wanted buttons with Pooh on them. She embroidered them herself with a beaded nose for the bear and sent the material to me. I made the buttons, which were going down the back of the dress. I said, ‘Please send me a picture of your wedding dress when it is finished.’ She sent me a picture of the front. So I never saw Pooh bear.

A lady stood in the doorway recently and asked me, ‘Do you sell the buttons?’ I replied, ‘No, it’s a museum.’ She walked away, I think she believed me.”

‘Presiding regally over her charges like the queen of the buttons’

Cutting a disc of satin

Placing it in the mould

Putting the mould into the press

Edwardian crochetted silk buttons

“I like those Italian buttons with cherries on them, they are my favourites”

Dickens’ card while resident, when Cleveland St was known as Norfolk St (reproduced courtesy of Dan Calinescu)

You may also like to read about

The First Punjabi Punk

Spitalfields Life Books is publishing A MODEST LIVING, Memoirs of Cockney Sikh by Suresh Singh next week and here is the sixth instalment.

In this first London Sikh biography, Suresh tells the story of his family who have lived in their house in Princelet St for nearly seventy years, longer I believe than any other family in Spitalfields. In the book, chapters of biography are alternated with a series of Sikh recipes by Jagir Kaur, Suresh’s wife.

You can support publication by ordering a copy now, which will be signed by Suresh Singh.

Click here to order a signed copy of A MODEST LIVING for £20

Suresh Singh & Jagir Kaur at 38 Princelet St this summer (Photograph by Patricia Niven)

Suresh (in the hat) with punk friends in Spitalfields, 1977

Encouraged by my Trotskyite, Leninist, Marxist and Maoist teachers at the City & East London College – and even Eddy Stride, Rector of Christ Church whose thinking was out on a limb – I became rebellious. I questioned everything and could no longer accept things as they were. I preferred to wear clothes from jumble sales and I looked different from other people. Dad appreciated that too. We both had swag. He was more of a snappy dresser and I was more of a punk.

He never minded when I got my ears pierced, and Mum heated up the needle so I could pierce my nose, a very do-it-yourself job. Dad understood my actions as being like the yogis who wore dreadlocks and painted their bodies with mud.

He preferred that I discovered my own expressions of identity instead of asking him, ‘Dad, can I buy a flash car?’ or even, ‘Can you give me the money for a pair of Nike trainers?’ He would rather I find a pair of old football boots, take the studs off the soles, shave them and make them into a nice pair of shoes by painting a Union Jack or something on them. He liked the sense of surprise and was curious to see what I would come up with. It was so exciting to me at fifteen years old. the courage to put two fingers up to the skinheads and say, ‘You try it now!’

I was an outsider. I was not inside the white community, I was not inside the Bengali community and I was not inside the Sikh community either, because Dad did not want me to be a stereotypical Sikh. So instead I chose the freedom of an anarchic existence.

I remember seeing a skinhead band, Screwdriver, in the student union at the Polytechnic in Whitechapel. The audience were entirely skinheads and I thought, ‘Oh shit, I’m going to die,’ because I was the only Asian there. But I am still here. At the Marquee in Soho, I went to see Generation X and Boomtown Rats. At the Acklam Hall in Portobello, I saw The Fall. All for fifty pence. Through word of mouth, I was able to catch Blues Dub sound systems nights in big basements in Notting Hill. These were exciting times.

In retrospect, I think it was less about rebellion and more about creativity. This explosion of musical culture in London came at the right time for me, just as I left school. The Rastafarians believed the world would end in 1977. Apparently Haile Selassie said that ‘When seven sevens clash, that is the year of reckoning.’

I started listening to the Sex Pistols, though I preferred the early days of Siouxsie & the Banshees before they were signed up. No-one would sign them at first because they did not know how to play their instruments and Siouxsie did not know how to sing, she just wailed like a banshee.

I was a good drummer, even though I had never learned how to play. I just picked up a pair of sticks because I used to play the flute at school and got bored with it. I used to play Dad’s Indian dholki (hand drum) quite a bit at home, so I knew I could do it. I got a drum kit that I bought out of the back of Melody Maker for twenty-five quid. It was a good kit made by Rogers. I practised at home in the back room in Princelet St. A lot of the time I rehearsed using just my drum sticks and telephone directories. I put the directories in place of the snare drum to practice without making noise, allowing me to strengthen my arm and wrist action.

I did not know Spizzenergi at all, although I heard through the grapevine that they were looking for a drummer. Spizz, the frontman, was a nice posh white kid from Solihull. He was living in Portobello Rd, where a lot of people were playing and rehearsing music in the squats. I used to cycle over. I found a bike in an abandoned Anderson shelter in Parfett St which meant I could travel all over London. I made new friends at City & East London College, including Mark Fineberg who lived in Belsize Park, so my social life expanded beyond the East End.

Spizz knocked on my door in Princelet St one day. I looked out of the window at the top of the house. He shouted, ‘Look, I’ve got a van here. Get your drums in the back, we’re going on tour with Siouxsie & the Banshees.’ I said, ‘Who?’ and he yelled, ‘Do you want to go on tour with us?’ So I asked, ‘Can I go, Dad? I’ve got a drum kit,’ and he said, ‘You’ve got a drum kit, so you can go.’

In true do-it-yourself spirit we put our records in plastic sleeves and and delivered them ourselves to Rough Trade in Portobello. I loved doing our John Peel session in November 1979 and seeing in 1980 at Au Plan K in Brussels. When we put out ‘Where’s Captain Kirk?’ it became a huge hit and the members of the band thought they were going to become pop stars. They wanted the sound to become more con- trolled and less spontaneous. I did not want us to end up sounding like a bunch of session players. I was Hero Shema, the drummer who never played in an orchestrated fashion. ‘Bollocks to this,’ I thought, ‘I’m shipping out.’ Dad always said, ‘If your ego overrides you, you’ve had it.’ I could see the egos expanding. I recognised the band were losing their edge. Dad said, ‘When that happens, just ship out.’ It was time to be in the world and not of it.

As an adolescent I loved the idea of not conforming – not being different just for the sake of it but to avoid becoming part of the status quo. By questioning, I learned different ways of doing things and different ways of thinking. It taught me to consider the value of things and resist becoming set in my ideas. At that time, black culture was becoming more accepted in this country and, through sharing music, people learned to respect other cultures. Most important for me was that I was not rebelling against my parents, which was quite different from my mates’ situations. They would tell me, ‘My dad hates me being a punk, I can’t even get out the house without my old man going “Who are the Boomtown Rats? And what are those trousers you’re wearing?”’

My parents’ acceptance of punk made me feel that it was of value and gave me more confidence in my own anarchic understanding of what was valuable in life. Dad was the same. He was holding two fingers up to the gurdwaras and the Sikhs, because he had his own way of living and being a Sikh. If your parents love and support you, you do not need to rebel against them because you know that they value you as an individual in your own right. Dad did not want to create another Joginder Singh, he wanted me to find my own identity as Suresh without losing my Sikhism.

Sometimes Sikhs would come round to our house and ask, ‘Why do you let your son pierce his nose?’ and Dad would say, ‘Well, he isn’t doing you any harm is he? Has he said anything to you? No? Well, let it be.’ Their sons would come round dressed up, wearing badly-fitted suits, they just looked terrible. Dad loved it and got off on winding people up – I actually think that was what gave him the edge.

Suresh plays drums for Spizzenergi at Lewisham Odeon 31st October 1979 (Photograph copyright © Philippe Carly)

The cover of Where’s Captain Kirk? reproduced courtesy of Spizz

Suresh’s cat Scratti named after Scritti Pollitti

Suresh Singh will be in conversation with Stefan Dickers at the Write Idea Festival at the Whitechapel Idea Store on Saturday November 17th at 1pm. CLICK HERE TO BOOK A FREE TICKET

Click here to order a signed copy of A MODEST LIVING for £20

Matyas Selmeczi, Silhouette Artist

Matyas Selemeczi is cutting silhouettes at the Huguenot Skills day next Saturday 20th October 11-4pm in Hanbury Hall and The Gentle Author is giving a lecture on the Small Trades of Spitalfields in the crypt of Christ Church at 11am. General admission is free but click here for tickets for workshops and lectures

With his weathered features, grizzled beard, sea captain’s cap and denim bib overalls, Silhouette Artist Matyas Selmeczi looks like he has just stepped off a boat and out of another century. For several years now, Matyas has been a fixture in Spitalfields and he is participating in the Huguenot Skills event next Saturday 20th where there will be the opportunity for you to have your silhouette done.

Such is his gentle, unassuming personality that it is possible you may not have noticed Matyas sitting in his booth, yet I urge you to seek him out because this man is possessed of a talent that verges on the magical. With intense concentration, he can slice through a piece of paper with a pair of scissors to produce a lifelike portrait in silhouette in less than three minutes, and he does this all day.

Once his subject sits in front of him looking straight ahead, Matyas takes a single considered glance at the profile and then begins to cut a line through the paper, looking up just a couple of times without pausing in his work, until – hey presto! – a likeness is produced. The medium is seemingly so simple and the effect so evocative.

Silhouettes were invented in France in the eighteenth century and named after Etienne de Silhouette, a finance minister who was a notorious cheapskate. These inexpensive portraits became commonplace across Europe until they were surpassed by the age of photography and when you meet Matyas, you know that he is the latest in a long line of silhouette artists on the streets of London through the centuries.

In spite of photography, silhouettes retain their currency today as vehicles to capture and convey human personality in ways that are distinctive in their own right. And for less than a tenner, getting your silhouette done is both a souvenir to cherish and an unforgettable piece of theatre.

“I have always been able to draw and I trained as an architect in St Petersburg. When my daughter was eight years old, I tried to teach her to draw but it was too early and she would cry. A pair of scissors were on the table so I picked them up and cut her silhouette to make her smile – that was my very first. When she was twelve, I was able to teach my daughter to draw and now she has become an architect.

In 2009, I was working in Budapest as an architect, but there was a crash in Hungary so I came to London. I found there was also a crash here, so I couldn’t get a job and I decided to do silhouettes instead. The first two years were hard but interesting. I did not know anything, I started in Trafalgar Sq. A friendly policeman explained that I could not charge, instead I had to ask for donations.

Then I was on the South Bank for two years and I used to have a line of people waiting to have their silhouettes done. In winter it was very hard, I had gloves and put my hands in my pockets to keep them warm so I was ready to work, but it was very windy and the wind blew away my easel and folding chair.

So four years ago, I came to Brick Lane where I can charge money but I have to pay rent, and I’ve been here every weekend since, and I am in Camden from Wednesday to Friday. On Monday and Tuesday, I am free to do my own drawing and painting.

To draw a portrait you start from the brow and draw the profile but with a silhouette you begin with the neck. It is like a drawing but you only make one line and you cannot make any mistake in the middle. It is like a shadow or a ghost. It takes me three minutes but it is not hard for me.

I like to do father and son, mother and daughter and it is very interesting to see the similarities and the differences, and how the profile changes over time.

Anybody can take photographs but silhouettes require skill. It is not really an art but a beautiful craft. You must have good eyes and very good hands.

The first time I saw a silhouette being cut was in Milos Forman’s ‘Ragtime.’ In the first few minutes of the film, you are in the Jewish quarter of New York and you see a silhouette artist on the street.

Once on the South Bank, I had a very old lady at the end of the queue watching me and I thought she had no money, so I offered to cut her silhouette for free – but she said, ‘No, I am a silhouette artist.’

She had come to this country as a child with her family from Vienna in the thirties escaping Hitler and cut silhouettes on the streets of London. Her name was Inge Ravilson and she was eighty-eight years old. She invited me to her home, and I visited her and we drank tea.

We became friends. She was wonderful and she taught me her tricks. She could cut a silhouette very fast, in one minute, and she told me I am too slow but my work is more characterful, so I was very proud. I know I am not the best, but she told me I am good and she gave me her scissors. That’s good enough for me.”

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

Matyas Selmeczi can be found in Spitalfields every weekend and is also available for parties, weddings and events.

You may also like to read about

So Long, Edward Burd

With great sadness, I must announce the passing of Edward Burd, Horologist of Camden Town, who died on Monday aged seventy-nine

Edward Burd

Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie & I made the trip to Camden Town to visit Edward Burd, Horologist, in a tottering house which surely had more clocks than any other in London. Meeting Edward made me realise how much I miss the reassuring sound of ticking, interspersed by regular chimes, which was once the universally familiar background of life yet is now slowly vanishing from the world.

“My father Lawrence Burd was a schoolmaster, and a man of obsessions that he would pursue to the highest possible level – photography, alpine gardening and horology. He did all the British Institute of Horology exams and became a Fellow of the Institute, then after about four years he dropped it completely. Just about that time, I was an irritating fourteen year old looking over his shoulder at what he was doing, asking ‘What’s that for?’ and ‘Why are you doing that?’ Instead of telling me to bugger off which any sensible person would do, being a patient schoolmaster, he explained to me what was going on and I was fascinated by it.

So from that age I have always been interested and I kept it up a bit but I became an architect and, while I was struggling to set up my own practice, I could not really do much about it. Yet I kept my hand in, I went to auctions and bought the odd clock. Then, when I retired about twenty years ago, while I still had a bit of energy left I thought I should pursue this thing seriously.

My speciality is English wall clocks which I always find interesting partly because they were never designed to go in drawing rooms, they were always the ‘workhorse’ clock which is why you see them in railway stations and schoolrooms. What I like about them is their mechanisms are very simple and extremely efficient and they are very good timekeepers. There’s no pretensions whatsoever in the design of the case. If they had been going in a drawing room, they would have looked very different. That always appealed to me, that they are unpretentious. Also, they were about the only thing I could afford when I first started. Added to which, if you studied them for a fairly short period of time, you probably knew more about them than most dealers.

Certainly, every town would have an antique shop in those days. They’d say, ‘That’s an old schoolroom clock, five pounds!’ I can remember going into one funny little shop somewhere out in the country and there were three round clocks on the floor, two were made in about 1920 and were pretty horrible and one was eighteenth century with a big wooden dial. I said, ‘How much are the clocks?’ ‘The clocks?’ he said, looking up from doing his racing tips, ‘The clocks are five pounds each,’ which was cheap even then. I couldn’t believe it. I said, ‘Even the big one?’ rather naively. ‘Yes it is a bit big,’ he replied, ‘You can have that for three and a half.’

My father taught me a lot, because he had to learn quite a lot of practical knowledge and make all sorts of things to become a member of the Institute of Horologists. I cannot do all that but, if the clock is not too complicated, I can do a basic overhaul of a wall clock.

Ten or fifteen years ago, it became a business. I would go to a sale to buy a nice clock for myself for my collection and I saw other good clocks being sold very cheaply, so I thought, ‘I could buy that and sell it’ – and it went on from there. I have quite a lot. My collection is about fifty but, altogether, I must have about a hundred and fifty to two hundred clocks.

After about 1840, nearly all clocks were made in factories in Birmingham or London, predominantly in London – Clerkenwell was the place for clocks. When I first became interested in the sixties, all the trades were still in Clerkenwell, supplying and fitting glass, engravers, gilders, dial-painters and materials shops. You could walk around and see them all in fifteen minutes.

My collection is English wall clocks dating from 1750 through to about 1900. The design of the cases changed quite a bit in that era but the movements remained exactly the same. There were not many wall clocks before 1750 because there were not many offices, they were made for solicitors’ offices around 1720 but there were few shops to speak of, it was all markets. An early English wall clock would be about 1780 and they were below stairs in big houses. It was only at the beginning of the nineteenth century that wall clocks became current and they did not become widespread until the 1840s.

A clock is a mechanical object which is comprehensible, these days you have no idea how any device works and, if it doesn’t work, you might as well sling it. Clocks are so incredibly easy to understand. You’ve got a spring, a chain, a series of wheels, the escapement and the pendulum. You wind it up to give it the power and isn’t that clever? So simple and so repairable. It works and it tells the time.

What gives it accuracy is not the escapement but the pendulum. The rate of oscillation depends upon the length of the pendulum. Most pendulums have a rod made of brass which is much easier to work than steel, but brass shrinks and expands much more than steel. So timekeeping with a brass pendulum is less accurate – within a couple of minutes a week – whereas a steel rod will keep time within about half a minute a week. At the end of the winter when night-time temperatures get low, you have to regulate them because the pendulum will shrink in the cold, become shorter, and the clock will go faster. A hot spell will make the metal expand and clock will slow down.

My early clocks were made by craftsmen without power tools or electric light, just working by flickering candles. It is extraordinary that they managed to produce clocks of such enormous quality and so accurate. I can sit and watch them for hours.

The sound is very important too. If you have had a hard day and it is raining and it has all been bit much, and you come in and there is this ticking, and you have a cup of tea and put your feet for a few minutes, then you are all right – it is looking after you, it has its own spirit.”

John Decka, Poplar c. 1785 (John Decka was apprenticed to William Addis, and is recorded working 1757-1806)

French, Royal Exchange c. 1860 (This clock was almost certainly built into the bulkhead of boat)

T.Rombach, 206 Grange Rd, Bermondsey c. 1900

Stubbs, Old Kent Rd c. 1870

Thwaites & Reed, Clerkenwell c. 1850

De St Leu, London c. 1785

W.A. Watkins, Carey St, Lincoln’s Inn c. 1870

Bray, 165 Tottenham Court Rd c. 1850

S. Mayer, 76 Union St, Borough c. 1890

Edward Burd, Horologist

Portraits copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

The Little Yellow Watch Shop

The Triumph of Doreen Fletcher

Cover of Doreen Fletcher’s monograph

Regular readers will be aware of the magnificent paintings of Doreen Fletcher which were first shown in these pages in 2015. Doreen painted the East End from 1983 until 2004, when she gave up in discouragement due to lack of interest in her work. Since 2015 Doreen has begun painting again, had two shows at Townhouse Spitalfields, and one of her paintings was shown at the National Gallery last year when she was shortlisted for the first Evening Standard Contemporary Art Award.

I am overjoyed to announce that there will be a major retrospective of Doreen Fletcher’s paintings at the Nunnery Gallery, Bow Arts opening 25th January and running until 17th March.

Complementing the exhibition, Spitalfields Life Books are publishing a handsome hardback book of Doreen Fletcher’s paintings on November 15th, collecting more of her pictures than have ever been seen together before and showing the full breadth of her achievement as a painter for the very first time.

There are two ways you can support this.

1. We are seeking readers who are willing to invest £1000 to make Doreen Fletcher’s book happen. If you can help, please drop me a line at spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

2. Preorder copies for yourself and your friends using the link below and we will send them to you signed by Doreen Fletcher on publication in November.

Click here to order a signed copy of DOREEN FLETCHER, PAINTINGS

Portrait of Doreen Fletcher in her studio by Stuart Freedman

One day in 2015, I received an email with a photograph of a painting by Doreen Fletcher attached at the end. It was quite an indistinct photo, just the size of a thumbnail, but I was immediately spellbound. It was a good painting. The picture had a rigorous structure, a mystery and an authority which drew my attention at once. It was quite unlike any painting I had seen.

I did not know anything about Doreen then, but I was fascinated to learn who she was. So I contrived a means to meet her. When I asked Doreen if she had any more paintings, she blushed and rolled her eyes, laughing. I discovered that Doreen had given up painting ten years earlier, discouraged by lack of interest in her work. Yet she told me she painted full-time for twenty years and when she stopped she had put all her paintings away in an attic.

Doreen let me persuade her to take her paintings down from the attic. It was obvious that these pictures comprised a significant body of work, of range, contrast and accomplishment. When I photographed these paintings and published them on Spitalfields Life, the response was immediate and positive. After decades of rejection, thanks to the democratising nature of the internet, Doreen discovered a passionate constituency who loved her work.

For artists, disappointment is a common experience. It is hard to accept that it is arbitrary whether your work coincides with the fashion of the day. So I hope Doreen’s example may prove an inspiration to others. It is not often that struggles are vindicated but I believe Doreen would confirm she has been vindicated beyond expectation.

In recent years Doreen’s atmospheric urban landscape paintings have reached a wide audience who appreciate her distinctive vision of the changing capital. She is getting the recognition she deserves, not just for the outstanding quality of her painting but also for her brave perseverance, pursuing her clear-eyed vision in spite of the lack of interest or support.

Bartlett Park, 1990

Terminus Restaurant, 1984

Bus Stop, Mile End, 1983

Terrace in Commercial Rd under snow, 2003

Shops in Commercial Rd, 2003

Snow in Mile End Park, 1986

Laundrette, Ben Jonson Rd, 2001

The Lino Shop, 2001

Caird & Rayner Building, Commercial Rd, 2001

Rene’s Cafe, 1986

SS Robin, 1996

Benji’s Mile End, 1992

Railway Bridge, 1990

St Matthias Church, 1990

The Albion Pub, 1992

Turner’s Rd, 1998

The Condemned House, 1983

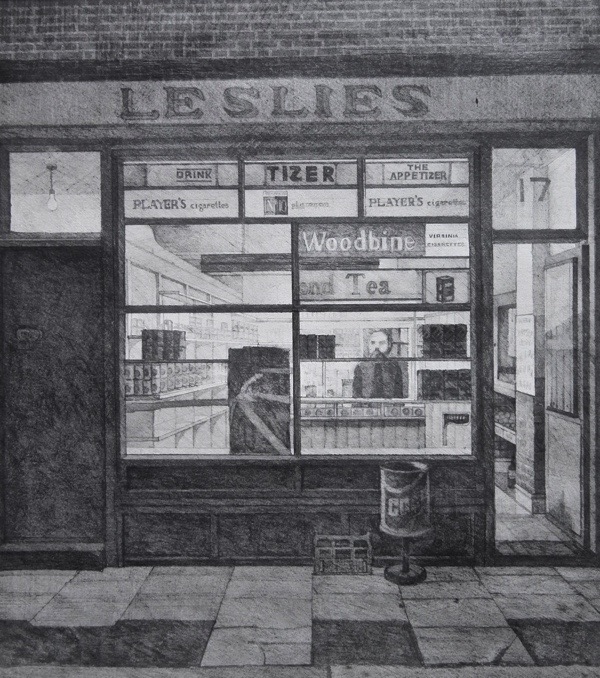

Leslie’s Grocer, Turner’s Rd, 1983 (Pencil Drawing)

Newsagents, Canning Town, 1991 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

Bridge Wharf, 1984 (Pencil Drawing)

Pubali Cafe, Commercial Rd, 1990 (Coloured Crayon Drawing)

The CR Ashbee Lecture 2018

Jewellery workshop at Guild of Handicraft in Bow, 1890s

Each year, the East End Preservation Society presents the CR Ashbee Memorial Lecture. The inaugural lecture was delivered by Oliver Wainwright on the Seven Dark Arts of Developers, the second lecture was delivered by Rowan Moore on The Future of London and last year Maria Brenton, Rachel Bagenal and Kareem Dayes spoke about Hope in the Housing Crisis.

This year’s CR Ashbee Memorial Lecture returns to its roots by taking the subject of CR ASHBEE IN THE EAST END and will be delivered by The Gentle Author at Bow Church on Monday 22nd October at 7:30pm

Perhaps more than anyone else, CR Ashbee tried to put the ideas of William Morris into practice. The lecture will explore Ashbee’s role in creating the Guild of Handicraft in Bow, in saving Trinity Green Almshouses from demolition and founding the East End Preservation Society in the eighteen-nineties.

The lecture offers an opportunity to visit the fourteenth century Bow Church which was repaired by CR Ashbee in the eighteen-nineties and has just completed a recent programme of repairs to the tower.

TICKETS ARE FREE BUT MUST BE BOOKED IN ADVANCE BY CLICKING HERE

This year’s CR Ashbee lecture will take place at Bow Church

[youtube R-ZpZG8JfuI nolink]

“To me, it is obvious that an East End Preservation Society is needed a) to gather and represent local opinion b) to help East London people stand together c) to give them a voice and make that voice count (to ensure it is not only heard but also that it is acted upon) and d) to reveal and promote an urban vision which is not governed by short-term and personal profit, but which evokes and embraces more worthy and more communal aims – and which enshrines the spirit and character of East London.

Our opinions – the opinions of ordinary Londoners – matter, and must not be cast aside by corporations or corporate politicians. United we stand, divided we fall.

If we become a coherent pressure group, national and local politicians and planners will be obliged to listen to us. We have much to lose but – if we stick together – much to gain.” – Dan Cruickshank

East End Preservation Society at Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

East End Yiddisher Jazz

Broadcaster Alan Dein introduces a new compilation of East End Yiddisher Jazz that he has uncovered, reclaiming a charismatic lost musical world from undeserved obscurity

Dancing in the street in Whitechapel

“Music is the Most Beautiful Language in the World!” proclaimed Weinberg’s Brick Lane gramophone shop in an advert published in a Yiddish paper sold on the streets of Whitechapel in the twenties. This was the time when swinging dance bands were all the rage, and local venues like St George’s Town Hall, the Grand Palais and the King’s Hall proudly hosted ‘Jazz dances’ complete with live bands and fox trot competitions. At Levy’s record shop, 19 & 20 Whitechapel High St, which was known both locally and far and wide as ‘the Home of Music’, customers could find the latest red hot jazz imports, and even discs pressed up on Levy’s very own record labels, Levaphone and Oriole.

This was a musical landscape in which generations of gifted young Jewish Eastenders – musicians, singers, song writers as well as impresarios, club and record shop owners – forged a remarkable contribution to the development of the British music scene. Take Bud Flanagan, Joe Loss, Stanley Black, Ronnie Scott, Alma Cogan, Lionel Bart and Georgia Brown to name but a few.

Their recorded legacy can easily be found online. Yet surprisingly, given the cultural and religious backdrop, Jewish-themed jazz and dance band discs, or folk or musical comedy numbers recorded in London during this time have proved far more elusive. There is no problem in finding their equivalent in the United States, or even Jewish dance band music from pre-Nazi era Germany or Poland. So my quest has been to seek out and rescue the ‘Yiddisher Jazz’ soundtrack of the old Jewish East End from apparent aural oblivion.

What treasures they are! Thanks to a squad of supporters and fellow travellers, I have traced a series of remarkable 78 rpm discs in the archives of the British Library and the Jewish Museum, as well as in private collections, and via the charity shops of Hendon and Golders Green. These were districts where former East Enders moved in the last century and where – sadly after they have gone – some of their possessions end up for sale. Yet even after all these years, these recordings are still very much alive. Magically, they have preserved an atmosphere of a past world – mirroring the old Yiddish Theatre where audiences left with smiles on their faces and tears in their eyes.

We can delight in the cheeky street patter of the incomparable slapstick drummer Max Bacon rejoicing in the East Enders love affair with ‘Beigels’ – but also shed a tear with Leo Fuld, the remarkable Dutch Yiddish singer, whose recordings in post-war London were haunting reminders of a way of life decimated by the Holocaust.

Local haunts like Petticoat Lane market are mentioned regularly in these recordings, and in 1929 Mendel & His Mishpoche Band offered lyrics sung in Yiddish to a pounding fox trot: “the women rush to get bargains, a chicken with schmaltz, a new sock, a bit of chrain, soup, a beigel with a hole, all this you can get in the Lane. A fish-sweet, half a kishke, an onion, fish, a meaty bone, a bride with a dowry, a woman looking for a husband, such things you can get in the Lane.”

Besides bands with fictitious monikers like Mendel’s where the actual names of the musicians have been lost in time, there are terrific Jewish-themed numbers by the hugely successful stars of the era, like Whitechapel boys Bert Ambrose and Lew Stone, whose BBC Radio broadcasts in the thirties made them household names throughout the nation.

It was an unexpected treat to discover a small run of releases by Johnny Franks & his Kosher Ragtimers, who recorded for the short-lived independent Planet label – which operated from a first floor flat in Stamford Hill at the beginning of the fifties. As a lad, Franks worked in his father’s kosher butcher shop, and by his early twenties he was composing and playing on a series of extraordinary recordings. His orchestra can be heard accompanying Chaim Towber, the Ukrainian-born star of the Yiddish Theatre, on perhaps the most well-known track in the collection – the classic ‘Whitechapel’. It is a poignant homage to a way of life that was disappearing in front of the singer’s eyes as the Jewish community of the area moves out to a suburban homeland.

Another highlight was a collection of 78 rpm discs by the Stepney-born siren of the Yiddish song, Rita Marlowe. Rita graduated from her synagogue choir to performing with dance bands in the pre-war years. She would later devote her career to performing solely in Yiddish, and her recordings were issued on Levy’s Oriole label. Founded in 1890 by Jack Levy selling bicycle parts in Petticoat Lane, Levy’s grew from the ‘Home of Music’ to running recording studios and owning labels and pressing plants, before merging with CBS in the sixties.

Thankfully the Beautiful Music has been preserved in the grooves of ancient discs. Now they are ready for a new journey, offering a nostalgic reunion for those who grew up listening to these songs, perhaps performed live at family functions, or in the ballrooms of the kosher hotel circuit of Brighton or Bournemouth – the British equivalent of the American ‘Borsht Belt.’ I hope the music will also excite a new generation intrigued by the rich social history of a place that has continued to absorb new cultures, and which has such a remarkable track record of inspiring musical creativity.

Advertisement from the twenties for Weinberg’s Gramophone Shop in Brick Lane

Sheet music for Petticoat Lane, A ‘Kosher’ Medley Foxtrot, 1929

Levy’s label

Advertisement for Levy’s, The Home of Music, Whitechapel

Lew Stone featured on a Radio Celebrities cigarette card, 1934

Max Bacon featured in Radio Pictorial, 1934

Label for Whitechapel released by Planet Recordings, 1951

Advertisement in the Jewish Chronicle in the fifties for Johnny Franks

Label for Why be Angry, Sweetheart? released by Oriole

The LP comes with a fold-out insert including a detailed essay by Alan Dein, illustrated with rare photos and memorabilia. CDs are available from jwmrecordings@gmail.com

You may also like to read about