Harry Harrison’s East End Portraits

David – universally known as ‘Harry’ – Harrison came to Mile End in 1979 and liked it so much he has never left. An artist who became an architect, he has recently retired from his career in architecture and become an artist again.

Tom was a gentle, polite and humble soul. His patch was between Mile End Station and the Roman Road and could be found most days in that area. He told me he was fifty-three years old when I painted him in 2014.

He wore a camel coat over a sleeping bag, over a denim jacket, over a fleece, over a jumper. I last saw Tom a couple of years ago outside Mile End Station and he looked very poorly.

I would love to hear that he survives somewhere still but I fear it is unlikely. I am moved by the depth of feeling in his forlorn expression. His obviously broken nose made me wonder if he may have once been a boxer?

Andrew inhabited a similar patch to Tom and, although seen as frequently, I never saw them together or at the same time. This painting also dates from 2014 and is in Mile End Park.

Unlike Tom, there was something defiant and angry about Andrew – even when offered money he could respond abusively. Yet he did once offer my wife a swig of his White Stripe, so he was not without chivalry.

Andrew would sometimes disappear for a few weeks and re-appear with a make-over, a haircut, clean shaven and with a set of new clothes. I was told that he was once a long distance lorry driver.

I saw Angus sitting on a bench in the evening sunshine in Old Street in 2017. What attracted me, apart from his extraordinary mane and facial hair was that he had a chess set set up on the pavement in front of him.

After striking up conversation, he challenged me to a game which I accepted. I am a poor player and out of practice, and I was hoping I may have stumbled upon an out of luck chess master.

I beat him rather quickly and easily, to my great disappointment and guilt – and Angus was gracious in defeat which made it even worse.

Anyone visiting Brick Lane in recent years could not fail to notice the stylish and urbane Mick Taylor. After completing this portrait I gave it to Mandi Martin who lives by Brick Lane and was a friend of Mick’s.

Mandi volunteers at St Joseph’s Hospice. In 2017, she spent some of Mick’s last few hours talking and reminiscing with him about their shared experiences of the East End.

In 2015, I met Tim sitting on a blanket and begging outside a cash machine in Shoreditch. He seemed young, sad and vulnerable, sitting eating crisps and surrounded by plastic bags of his belongings. Tim was reluctant to talk and seemed embarrassed by his situation. I have not seen him since.

This is my portrait of Gary Arber whose former printworks in the Roman Rd is a short walk from my home. Gary’s grandparents opened the shop in 1897 and Gary ran it for sixty years after after sacrificing a career as a flying ace in the Royal Air Force in 1954.

Paintings copyright © Harry Harrison

You may also like to read about

In The Charnel House

I wonder if those who work in the corporate financial industries in Bishop’s Sq today ever cast their eyes down to the cavernous medieval Charnel House of c. 1320 beneath their feet, once used to store the dis-articulated bones of many thousands of those who died here of the Great Famine in the fourteenth century.

Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Jane Siddell, believes starving people flooded into London from Essex seeking food after successive crop failures and reached the Priory of St Mary Spital where they died of hunger and were buried here. It was a dark vision of apocalyptic proportions on such a bright day, yet I held it in in mind as we descended beneath the contemporary building to the stone chapel below.

At first, you notice the knapped flints set into the wall as a decorative device, like those at Southwark Cathedral and St Bartholomew the Great. London does not have its own stone and Jane pointed out the different varieties within the masonry and their origins, indicating that this building was a sophisticated and expensive piece of construction subsidised by wealthy benefactors. A line of small windows admitted light and air to the Charnel House below, and low walls that contain them survive which would once have extended up to the full height of the chapel.

When you stand down in the cool of the Charnel House, several metres below modern ground level, and survey the neatly-faced stone walls and the finely-carved buttresses, it is not difficult to complete the vault over your head and imagine the chapel above. Behind you are the footings of the steps that led down and there is an immediate sense of familiarity conveyed by the human proportion and architectural detailing, as if you had just descended the staircase into it.

This entire space would once have been packed with bones, in particular skulls and leg bones – which we recognise in the symbol of the skull & crossbones – the essential parts to be preserved so that the dead might be able to walk and talk when they were resurrected on Judgement Day. Yet they were rudely expelled and disposed of piecemeal at the Reformation when the Priory of St Mary Spital was dissolved in 1540.

Brick work and the remains of a beaten earth floor indicate that the Charnel House may have become a storeroom and basement kitchen for a dwelling above in the sixteenth century. Later, it was filled with rubble from the Fire of London and levelled-off as houses were built across Spitalfields in the eighteenth century. Thus the Charnel House lay forgotten and undisturbed as a rare survival of fourteenth century architecture, until 1999 when it was unexpectedly discovered by the builders constructing the current office block. Yet it might have been lost then if the developers had not – showing unexpected grace – reconfigured their building in order to let it stand.

Around the site lie stray pieces of masonry individually marked by the masons – essential if they were to receive the correct payment from their labours. Thus our oldest building bears witness to the human paradox of economic reality, which has always co-existed uneasily with a belief in the spiritual world, since it was a yearning for redemption in the afterlife that inspired the benefactors who paid for this chapel in Spitalfields more than seven centuries ago

The exterior walls are decorated with knapped flints, faced in Kentish Ragstone upon a base of Caen Stone with use of green Reigate Stone for corner stones

Window bricked up in the sixteenth century

Inside the Charnel House once packed with bones

Twelfth century denticulated Romanesque buttress brought from an earlier building and installed in the Charnel House c.1320 – traces of red and black paint were discovered upon this.

Fine facing stonework within the Charnel House

Fourteenth century masons’ marks

The Charnel House is to be seen in the foreground of this illustration from the fifteen-fifties

The Charnel House during excavations

You may also like to read about

John Claridge At Whitechapel Bell Foundry

John Claridge first visited the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in 1982 to photograph the life of Britain’s oldest manufacturing company, founded in 1570 – and he returned 2016 to take another set of pictures. Remarkably, little changed in the intervening years.

‘When I got into the foundry all the work had finished, it was deserted,’ he told me, ‘it was like walking through a time portal or boarding the Mary Celeste. There was a very tactile feeling about the place, where craftsmanship held sway, and my pictures pay testament to that feeling.’

You can help save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry as a living foundry by submitting an objection to the boutique hotel proposal to Tower Hamlets council. Please take a moment this weekend to write your letter of objection. The more objections we can lodge the better, so please spread the word to your family and friends.

HOW TO OBJECT EFFECTIVELY

Use your own words and add your own personal reasons for opposing the development. Any letters which simply duplicate the same wording will count only as one objection.

1. Quote the application reference: PA/19/00008/A1

2. Give your full name and postal address. You do not need to be a resident of Tower Hamlets or of the United Kingdom to register a comment but unless you give your postal address your objection will be discounted.

3. Be sure to state clearly that you are OBJECTING to Raycliff Capital’s application.

4. Point out the ‘OPTIMUM VIABLE USE’ for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry is as a foundry not a boutique hotel.

5. Emphasise that you want it to continue as a foundry and there is a viable proposal to deliver this.

6. Request the council refuse Raycliff Capital’s application for change of use from foundry to hotel.

WHERE TO SEND YOUR OBJECTION

You can write an email to

planningandbuilding@towerhamlets.gov.uk

or

you can post your objection direct on the website by following this link to Planning and entering the application reference PA/19/00008/A1

or

you can send a letter to

Town Planning, Town Hall, Mulberry Place, 5 Clove Crescent, London, E14 2BG

You may also like to read about

Nigel Taylor, Tower Bell Manager

Hope for The Whitechapel Bell Foundry

A Petition to Save the Bell Foundry

Save the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

So Long, Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Click here to order a copy of John Claridge’s EAST END for £25

Terry Barns, Knot Tyer

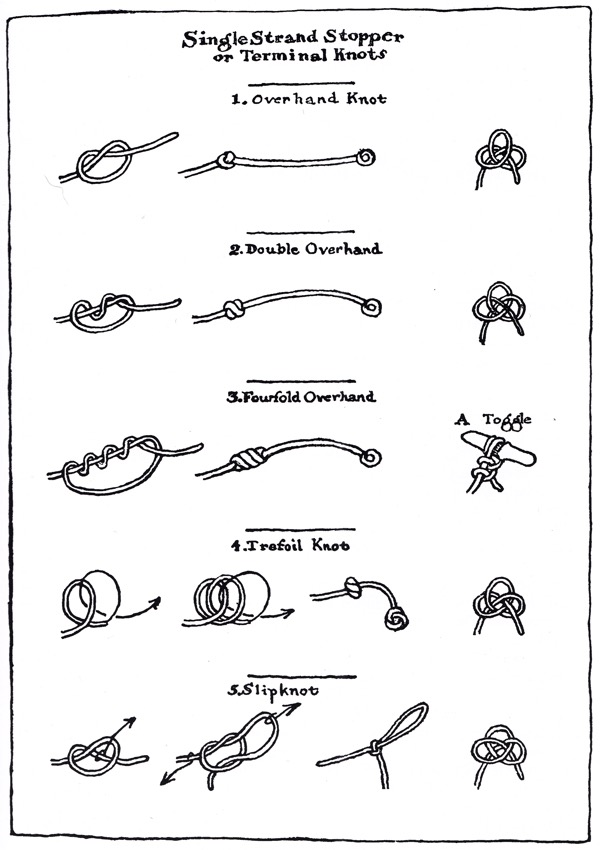

‘There isn’t really a word for it in English,’ admitted Terry Barns, ‘in French, they call it ‘matelotage’ meaning ‘sailors’ knot-making.’

Terry did not become a serious knot tyer until his fifties, yet it was a tendency that revealed itself in childhood. Celebrating the Queen’s Coronation in 1952, when Terry was just nine years old, his mother made him a guardsman’s outfit from red and black crepe paper with a busby fashioned from the shoulders cut out of an old fur coat. Terry’s contribution was to make the chin strap. ‘We got some gold string and I tied reef knots over a core, making what I now know is known as a ‘Pilgrim’s Sennet’ or a ‘Soloman’s Bar,’ he explained to me in wonder at his former precocious self, ‘but I never thought anything about it at the time.’

This is how Terry tells the story of the intervening years –

‘My early life was in the Queensbridge Rd but I was born in Hertfordshire because Hitler was trying to blow up the East End in 1944. My mum was a dress machinist and my dad was a wood machinist, he used to drill the holes in bagatelles and I still have one he made at home. In 1950, when I was six, we got a Council House in Clapton with a bathroom and an inside toilet – it was wonderful.

Somehow, I passed the 11-plus and ended up at Grocers’ Company School in Hackney Downs. When I left school at fourteen, being a prudent person, I joined the General Post Office as a telephone engineer, running around Mare St and Dalston. Nobody told me I could have stayed on at school and I soon realised that if I didn’t leave the GPO, I’d never know anything else. So I became a ‘Ten Pound Pom’ and went off to Australia in 1966.

I met my wife Carol in Pedro St in Hackney at that time and she followed me to Australia shortly after. I was a very quick learner and I had a very good job in Sydney working for a Japanese telephone company, Hitachi, but we had no intention of staying and came back in 1968. Then we got married in 1969, had three children and bought a house, so that occupied me for the next twenty years! I went back to the GPO which became BT and, when I was fifty, they asked if I would like to take some money and not go back again. So I have been living on my BT pension for the past twenty years and that has been the story of my life.’

Yet, all this time that Terry had been working with telephone cables, his tendency with string and rope had been merely in abeyance. ‘In the seventies, my wife bought me a copy of The Ashley Book of Knots,’ he revealed, bringing out a pristine hardback copy of the knotter’s bible containing nearly four thousand configurations. At a stall outside the Maritime Museum in Greenwich, Terry came across the International Guild of Knot Tyers which led to a four day course with legendary knot tyer, Des Pawson in 1994. ‘He’s got a museum of rope work in his back garden,’ Terry confided in awe.

‘I’m an engineer, but Des – he’s artistic,’ Terry informed me, ‘he educated me how to see things, he showed me when things look right.’ For over ten years, Terry has been on the Council of the Guild of Tyers, accompanying Des as his bag man, demonstrating knot work at festivals of matelotage in France – ‘My kind of holiday,’ he describes it enthusiastically.

When a sculptor cast a rope in bronze to symbolise the identity of the East End, it was Terry who wound the strands – and you can see the result at the junction of Sclater St and Bethnal Green Rd today. The largest pieces of rope you ever saw are placed as features in Terry’s front garden in Woodford. Inside the house, walls are hung with nautical paintings and shelves are lined with volumes of maritime history. They tell the story of one man’s lifetime entanglement with cable, rope and string, and remind of us of how the East End was built upon the docks, of which the ancient and ingenious culture of rope work was a major thread, still kept alive by enthusiasts like Terry Barns.

Terry with one he tied earlier

You might like to find out more at International Guild of Knot Tyers

You may also like to read about

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

In Spitalfields, an area of London defined by markets, I am constantly aware of the traders and the ever-changing drama of street life in which they are the star performers that draw the crowds. Interviewing market traders taught me that although they are here to make a living, it is an endeavour which may be described as culture as much as it is commerce. In fact, the markets prove so engaging to some as a location of social exchange that they carry on coming for the sake of it, even if they are not making any money.

This fascination with the culture and performance of market places led me to delight in the diverse sets of the Cries Of London for the pictures they give of street traders down through the ages. Even though they are frequently sentimentalised, these portraits also reveal the affection with which Londoners held the traders, celebrating the ingenuity of the identities created by vendors and casting them as the celebrities of the thoroughfare – collectively expressive of the personality of the city itself, when the streets were full of people with wares of every description to sell.

With the Cries of London, there is always a story behind each of the portraits and Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries from the nineteenth century, hand-tinted and produced in a pamphlet with a blue paper wrapper for sixpence, engages the readers with rhymes that complement the pictures and invite respect for the hawkers. The well-to-do woman in the frontispiece leading her daughter down the street shows deference to a Lavender Girl in a dress stained with mud around the hem, and this pamphlet can be read as an interpretation of the lives of the traders for the mother to read to her child.

The Lavender Girl walked into London carrying the lavender she picked that morning in the fields. The Band Box Man is selling the hat boxes that are product of his cottage industry, manufactured at home and sold on the streets, while. The Vegetable Seller is a Costermonger, buying his fruit at the wholesale market and hawking it around the street, as many did at Covent Garden and Spitalfields Markets. We are reminded that the Knife Grinder provides a public service in the home and workplace, while the Mackerel Girl has no choice but to carry her basket of fish around the city from Billingsgate, which she herself may not get to eat. The mishap of the Image Seller, in comic form, even illustrates the vulnerability of the street seller who relies upon trading to earn a crust and the responsibility of the customer to permit them a living.

For hundreds of years, popular prints and pamphlets of the Cries of London presented images of the outcast and the poor, yet permitted them dignity in performing their existence as traders. The Cries of London celebrate how thousands sought a living through street-selling and, by turning it into performance, gained esteem and moral ownership of the territory – transcending their economic status and creating the vigorous culture of street markets that persists to this day.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

More of Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Adam Dant’s New Cries of Spittlefields

CLICK TO BUY A SIGNED COPY OF THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S CRIES OF LONDON

Anthony Cairn’s Lost East End Pubs

When I discovered Antony Cairns‘ series of pub pictures, I realised I had found a kindred spirit. His soulful photographs manage to record the death and evoke the life of these lost hostelries simultaneously.

An East Ender who studied photography at the London College of Printing in the nineties, Antony printed these intriguing pictures using the Van Dyke Brown process which was commonly used at the end of the nineteenth century when these pubs were in their prime.

The Albion, Bow Common – (1881-2005)

The Railway Arms, Sutton St – (1881-2001)

The Conqueror, Austin St/Boundary St – (1899-2001)

The Rose, Woolwich

The Flying Scud, Hackney Rd – (1874-1994)

The Crown & Cushion, Market Hill, Woolwich – (1840-2008)

The Victoria, Woolwich Rd, Charlton – (1881-?)

The Tidal Basin, Canning Town – (1862-1997)

The Marquis of Lansdowne – (1838- 2000 & now being restored)

Photographs copyright © Antony Cairns

You may also like to take a look at

Alex Pink’s East End Pubs, Then & Now

Schrodinger Pleases Himself

When Shoreditch Church Cat, Schrodinger, came to live with me in Spitalfields last year, I put him down on the old armchair where my previous cat Mr Pussy always slept. Yet Schrodinger is significantly larger than his predecessor and, although he sometimes dozes curled up in the armchair, he prefers to be able to stretch out at full length on the sofa when he is sleeping.

Occasionally, in those early months, Schrodinger would sit at one end of the sofa if I sat at the other end, but mostly he required a monopoly of any piece of furniture and would leap up in a fit of pique if I sat down beside him. When the winter arrived, the luxurious novelty of stretching out on the turkish carpet in front of the fire proved irresistible, especially after the long winters he passed in Shoreditch Church with its bare stone floors. But as soon as I went to bed, he would always leap up onto the sofa and fill the warm space I had vacated, snoring the night away.

There were a couple of instances when I walked into kitchen to make a late night cup of tea and returned to discover Schrodinger had already settled down for the night in my place, stretching out to fill the whole sofa. As I entered the room, there would be an uneasy moment of mutual recognition before he skulked away in disappointment to wait beside the hearth, until I went to bed and he could reclaim his spot. Schrodinger only stirred himself from his ease on the sofa when it became apparent that if he did not shift I would sit on top of him.

Once – to spare Schrodinger the inconvenience of moving – I lay down upon the rug in front of the fire to rest upon the carpet and fell asleep. When I awoke with a shiver after the fire had died, I looked up to see Schrodinger peering down at me from his superior position on the sofa and realised our places had been reversed. I was disappointed at my weary acquiescence, submitting so readily to his over-inflated feline ego.

As Schrodinger became accustomed to our long winter nights together in front of the fire, sometimes I sat beside him on the rug to share the languorous warmth. I found that if I supported my back against the sofa and extended my legs at angles, Schrodinger was comfortable to occupy the ‘v’ shaped space in between. If I fell asleep, stretched out on the sofa, I awoke to find him sleeping, extended to his full length beside me. Thus it was that equality of the species was achieved in our household.

Around this time, Schrodinger acquired the habit of leaping up into the space between me and the back of the chair whenever I sat at my desk. Sometimes, he climbed around to sit upon my knees. By then, he was comfortable to sit beside me on the sofa and no longer always got up when I sat down.

So it was that the momentous yet inevitable day arrived. I was sitting upon the sofa in front of the fire when Schrodinger entered the room, came over and jumped unto my lap for the first time. He settled down, making himself comfortable before falling asleep, but I sat in surprise and wonder at this milestone in our relationship. Foolishly, I was overcome with flattery at this honour that Schrodinger had bestowed upon me. For months he had been assessing my nature and concluded that I am worthy of his attention, especially when it is cold and he wants somewhere warm to sleep.

The dichotomy of Schrodinger on the rug and me on the sofa is no more. Naturally, he still likes to stretch out in front of the fire but – if it pleases him – he can also choose to sit upon my lap on the sofa. From this position, it is only a small adjustment for Schrodinger to move to occupy the entire sofa when I retreat to my bedroom, leaving him to slumber at ease in the residual warmth.

You may also like to read about

Schrodinger’s First Winter in Spitalfields

Schrodinger, Shoreditch Church Cat

CLICK HERE TO ORDER TO A SIGNED COPY FOR £15