Sally Flood, Poet

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR FOR AUGUST, SEPTEMBER & OCTOBER

“I had always written, as a child,” admitted Sally Flood with a shrug, “but it wasn’t stuff you showed.” For years, when her thoughts wandered whilst working in the factory in Princelet St, Sally wrote poems on the paper that backed the embroidery in the machine she operated – but she always tore up her compositions when her boss appeared.

Then, when she was fifty years old, Sally took some of her poems along to the Basement Writers in Cable St and achieved unexpected recognition, giving her the confidence to call herself a poet for the first time. Since then, Sally’s verse has been widely published, studied in schools and universities, and she has become an experienced performer of her own poetry. “At work, I used to write things to make people laugh,” she explained, “I used to say, ‘Embroidery is my trade, but writing is my hobby.'”

“I’ve got draws full of poems,” she confided to me with a blush, unable to keep track of her prolific writing, now that poetry is her primary occupation and she no longer tears up her compositions. “I’ve got so much here, I don’t know what I’ve got.” she said, rolling her eyes at the craziness of it.

Ambulance helicopters whirl over Sally’s house, night and day, the last in a Georgian terrace which is so close to the hospital in Whitechapel that if you got out of bed on the wrong side you might find yourself in surgery. Sally moved there nearly fifty years ago with her young family, and now she has three grandchildren and five great grandchildren. Framed pictures attest to the family life which filled this house for so many years, while today boxes of toys lie around awaiting visits by the youngest members of her clan.

“In 1975, when my children were growing up and the youngest was fifteen, I decided that I need to do something else, because I didn’t want to be one of those mothers who held onto her children too much.” Sally recalled, “So I joined the Bethnal Green Institute, and it was all ballroom dancing and keep fit, but I found a leaflet Chris Searle had put there for the Basement Writers, so I decided to write a poem and send it along to them. Then I got a letter back asking me to send more – and I was amazed because the poem I sent was one I would otherwise have torn up. Of your own work, you’ve got no real opinion.”

“On my first visit, I went along with my daughter, but there were children of school age and I was turning fifty. I wasn’t sure if I should be there until I met Gladys McGee who was ten years older than me. She was so funny, I learnt so much from her – she had been an unmarried mother in the Land Army. I started going regular, and the first poem I read was published.”

“I think my life is more in poetry than anything else. I sometimes think my writing is like a diary. Chris Searle of the basement writers made such an impression on my life, he gave me the confidence to do this. And when I did my writing, my life took off in a certain direction and I met so many fantastic people.”

Sally’s house is full of cupboards and cabinets filled of files of poems and pictures and embroidery, and the former yard at the back has become a garden with luscious fuchias that are Sally’s favourites. After all these years of activity, it has become her private space for reflection. Sally can now get up when she pleases and enjoy a jam sandwich for breakfast. She can make paintings and tend her garden, and write more poems. The house is full with her thoughts and her memories.

“My grandparents were from Russia and they brought my father over when he was four years old.” Sally told me, taking down the photograph to remind herself,“He became cabinet maker and he was one of the best. In those days, they used to work from six until ten at night, so they knew what work was. I was born in Chambord St, Brick Lane, in 1925, and I grew up there. From there we moved to a two-up two-down in Chicksand St and from there to Bethnal Green, just before the war broke out. We had a bath in the kitchen with a tabletop. It was the first time we had a bath, before that we went to bathhouse. I’m telling you the history of the East End here!

I was evacuated to Norfolk at first. We took the surname Morris from father’s first name, so that people wouldn’t know we were Jewish. The people up there had a suspicion against Londoners and they thought we were all the same. But I was lucky, we ended up in a hotel on the river in Torbay in Devon. Life was fantastic, we used to go fishing. It was a different experience from my life in London. I joined the girl guides, I could never have done that otherwise. Where I was evacuated, they wanted to train me to be a teacher, but my mother came and took me back and said, “They’re going to exploit you, you’re going to be a machinist.”

“Being evacuated meant I went outside my culture, and I saw that English people were nice. I think that’s why I married outside my religion. We were together fifty-five years and I always say it wasn’t enough. If I hadn’t been evacuated I wouldn’t have done that.”

Sally put the photograph of her parents back on the shelf carefully, and turned her head to the pictures of her husband, her children, her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, on different sides of the room. I watched her looking back and forth through time, and the room she inhabited became a charged space in between the past and the future. This is the space where she does her writing. And then Sally brought out a book to show me, opening it to reveal it short poems in her handwriting accompanied by lively drawings of people, reminiscent of the sketches of L. S. Lowry or the doodles of Stevie Smith.

Sally is a paradoxical person to meet. A natural writer who resists complacency, she continues to be surprised by her own work, yet she is knowledgeable of literature and an experienced teacher of writing. Appearing at the door in her apron and talking in her tender sing-song voice, Sally wears her erudition lightly, but it does not mean that she is not serious. With innate dignity and a vast repertoire of stories to tell, Sally Flood is a writer who always speaks from the truth of her own experience.

Maurice Grodinsky, Sally’s father is on the left with Sally’s mother, Annie Grodinsky, on the right, and Freda, Maurice’s mother, in between. At four years old, Maurice was brought to Spitalfields from Bessarabia at the end of the nineteenth century. The two children are Marie and Joey – when this picture was taken in 1925, Sally was yet to be born.

Sally with her first child Danny in the early nineteen fifties.

Sally’s children, Maureen, Jimmy, Pat and Theresa in the yard in Whitechapel in 1962.

Sally’s husband, Joseph Flood.

Sally in Whitechapel, early sixties.

Sally with her children, Danny, Theresa, Jimmy, Maureen, Pat and Michael.

Sitting by the canal in the nineteen seventies.

Sally with Gladys McGee at the Basement Writers.

You may also like to read about

Chris Searle & the Stepney School Strike

or

Charles Booth’s Spitalfields

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR FOR AUGUST, SEPTEMBER & OCTOBER

In the East London volume of Charles Booth’s notebooks of research for his Survey into Life & Labour of the People of London (1886-1903), I came upon an account of a visit to Spitalfields in spring 1898, when he walked through many of the streets and locations around the same time Horace Warner took his Spitalfields Nippers photographs. So I thought I would select descriptions from Booth’s notebooks and place Warner’s pictures alongside, comparing their views of the same subject.

March 18th Friday 1898 – Walk with Sergeant French

Walked round a district bounded to the North by Quaker St, on the East by Brick Lane and on the West by Commercial St, being part of the parish of Christ Church, Spitalfields.

Back of big house, Quaker St

Starting at the Police Station in Commercial St, East past St Stephen’s Church into Quaker St. Rough, Irish. Brothels on the south side of the street past the Court called New Square. Also a Salvation Army ‘Lighthouse’ which encourages the disreputable to come this way. The railway has now absorbed all the houses on the North side as far as opposite Pool Square. Wheler St also Rough Irish, does not look bad, shops underneath.

Courts South of Quaker St – Pope’s Head Court, lately done up and repaired, and a new class in them since the repairs, poor not rough. One or two old houses remaining with long weavers’ windows in the higher storeys.

New Square, Rough, one one storey house, dogs chained in back garden…

Pool Sq

Pool Square, three storeyed houses, rough women about, Irish. One house with a wooden top storey, windows broken. This is the last of an Irish colony, the Jews begin to predominate when Grey Eagle St is reached. These courts belong to small owners who generally themselves occupy one of the houses in the courts themselves.

Isaac Levy

Grey Eagle St Jews on East side, poor. Gentiles, rough on West side, mixture of criminal men in street. Looks very poor, even the Jewish side but children booted, fairly clean, well clothed and well fed. Truman’s Brewery to the East side. To Corbet’s Court, storeyed rough Irish, brothels on either side of North end.

Washing Day

Children booted but with some very bad boots, by no means respectable….

Pearl St

Great Pearl St Common lodging houses with double beds – thieves and prostitutes.

South into Little Pearl St and Vine Court, old houses with long small-paned weavers windows to top storeys, some boarded up in the middle. On the West side, lives T Grainger ‘Barrows to Let’

Parsley Season in Crown Court

Crown Court, two strong men packing up sacks of parsley…

Carriage Folk of Crown Court – Tommy Nail & Willie Dellow

The Great Pearl St District remains as black as it was ten years ago, common lodging houses for men, women and doubles which are little better than brothels. Thieves, bullies and prostitutes are their inhabitants. A thoroughly vicious quarter – the presence of the Cambridge Music Hall in Commercial St makes it a focussing point for prostitutes

Detail of Charles Booth’s Descriptive Map of London Poverty 1889

At Abbey Wood

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR MY TOURS FOR AUGUST, SEPTEMBER & OCTOBER

Serving Hatch

Only recently did I learn that there is an abbey and a wood at Abbey Wood. Stunned by my own obtuseness, I set out to discover what I have been missing all these years. Visiting ruins was a memorable feature of childhood holidays, leaving a residual affection for architectural dereliction that has persisted throughout my life.

There is a familiar style of presentation in which the broken fragments of wall are neatly cemented in place while the former internal spaces are replaced by manicured lawns. This is the case at Lesnes Abbey in Abbey Wood, augmented with simple metal signs indicating ‘kitchen’ or ‘garderobe’ which set the imagination racing.

On leaving Abbey Wood station, my enthusiasm was such that I headed straight up the hill into the woods where I was overjoyed to discover myself entirely alone in an ancient forest of chestnut trees, filled with squirrels busily harvesting the chestnuts and burying them in anticipation of winter. Descending by a woodland path was perhaps the best way to discover the old abbey, situated upon a sheltered plateau beneath the hills yet raised up from the Thames and commanding a splendid view towards London.

Lesnes Abbey of St Mary & St Thomas the Martyr was founded in 1178 by Richard de Lucy, Chief Justice of England, as penance for the murder of Thomas A Becket. Richard retired here once the abbey was complete but died within three months. For centuries, the abbey struggled with the cost of maintaining the river banks and maintaining the marshlands productively. As a measure of how far it declined, it was closed by Cardinal Wolsey in 1525 as part of programme of shutting monasteries of less than seven residents, before the abbey was eventually destroyed in 1542 as one of the first to be subjected to the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

After demolition, the building materials were salvaged and the abbey was forgotten until Woolwich & District Antiquarian Society rediscovered it, excavated the ruins in 1909 and the site became a park in 1930.

I stood to gaze upon the ancient ruins and lifted my eyes in contemplation of the distant towers of contemporary London, wondering where the events of our time will lead. Then I walked back up into the forest and it crossed my mind that I if I followed the woodland paths long enough and far enough, maybe I could come back down the hill and enter the time when the abbey flourished and witness it as it was once, full of life.

Stairs to dormitory

The burial place of the heart of Roesia of Dover, great great granddaughter of the founder of this abbey, Richard de Lucy

West door of the church

Four hundred year old Mulberry tree, dating from the reign of James I

You may also like to read about

A Couple Of Pints With Tony Hall

CLICK HERE TO BOOK FOR MY TOURS & BUY GIFT VOUCHERS

Libby Hall remembered the first time she visited a pub with Tony Hall in the nineteen sixties – because it signalled the beginning of their relationship which lasted until his death in 2008. “We’d been working together at a printer in Cowcross St, Clerkenwell, but our romance began in the pub on the night I was leaving,” Libby confided to me, “It was my going-away drinks and I put my arms around Tony in the pub.”

During the late sixties, Tony Hall worked as a newspaper artist in Fleet St for The Evening News and then for The Sun, using his spare time to draw weekly cartoons for The Labour Herald. Yet although he did not see himself as a photographer, Tony took over a thousand photographs that survive as a distinctive testament to his personal vision of life in the East End.

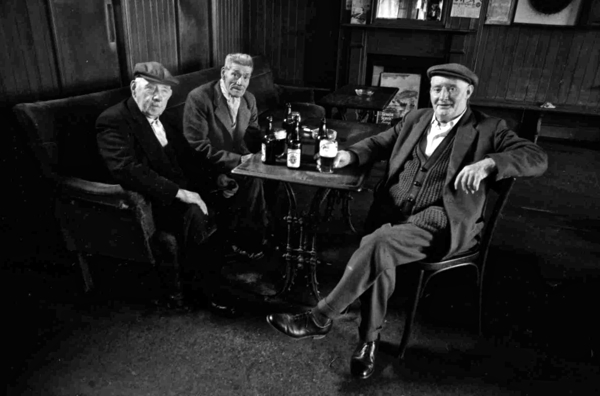

Shift work on Fleet St gave Tony free time in the afternoon that he spent in the pub which was when these photographs, published here for the first time, were taken. “Tony loved East End pubs,” Libby recalled fondly, “He loved the atmosphere. He loved the relationships with the regular customers. If a regular didn’t turn up one night, someone would go round to see if they were alright.”

Tony Hall’s pub pictures record a lost world of the public house as the centre of the community in the nineteen sixties. “On Christmas 1967, I was working as a photographer at the Morning Star and on Christmas Eve I bought an oven-ready turkey at Smithfield Market.” Libby remembered, “After work, Tony and I went into the Metropolitan Tavern, and my turkey was stolen – but before I knew it there had been a whip round and a bigger and better one arrived!”

The former “Laurel Tree” on Brick Lane

Photographs copyright © Estate of Libby Hall

Images Courtesy of the Tony Hall Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read

Old Mother Hubbard & Her Wonderful Dog

Courtesy of Jemmy Catnach of Catnach Press, it is my pleasure to publish this early nineteenth century shaggy dog tale of the devoted Mother Hubbard – believed to be by Sarah Catherine Martin

You may also like to read about

Libby Hall, Collector of Dog Photography

At St Botolph’s School House

If you want to know the story of the splendid pair of statues of schoolchildren upon the front of the former School House at St Botolph’s in Bishopsgate, Reg the Caretaker is your man. “When this was a school, these statues used to be in colour – the children repainted them each year – and then we sent them away for a whole year to get all the layers removed,” he explained to me with a sigh. “When they came back, people tried twice to nick them, so then we put them inside but the Council said, ‘They’re listed,’ and we had to send them away again for another year to get replicas cast.”

Old photographs show these figures covered in gloss paint and reduced to lifeless mannequins, yet these new casts from the originals – now that the paint has been removed – are startlingly lifelike, full of expression and displaying fine details of demeanour and costume. The presence of the pair in their symmetrical niches dramatically enlivens the formality of the architecture of 1820 and, close up, they confront you with their implacable expressions of modest reserve. Quite literally, these were the model schoolchildren for the generations who passed through these doors, demure in tidy uniforms and eagerly clutching their textbooks. Their badges would once have had the image of a boy and a sheep with the text, “God’s providence is our inheritance.”

“It’s Coade stone – the woman died with the recipe, but now they’ve rediscovered it again,” added Reg helpfully and – sure enough – upon the base of the schoolboy are impressed the words “COADE LAMBETH 1821.” Born in Exeter in 1733, Eleanor Coade perfected the casting process and ran Coade’s Artificial Stone Manufactory from 1769 at a site on the South Bank, until she died in 1821 aged eighty-eight – which makes these figures among the last produced under her supervision. Mrs Coade was the first to exploit the manufacture of artificial stone successfully and her works may still be seen all over London, including the figures upon Twinings in the Strand, the lion upon Westminster Bridge and the Nelson pediment at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich.

Reg took me inside to show me St Botolph’s Hall, lined with oak panelling of 1725 from a demolished stately home in Northamptonshire, where the two original statues peer out from behind glass seemingly bemused at the corporate City functions which commonly occupy their school room now. The Bishopsgate Ward School was begun in 1820 by Sir William Rawlins, a Furniture Maker who became Master of the Worshipful Company of Upholders and Sheriff of the City of London. In twenty years as Treasurer, he had lifted the institution up from poverty and it opened on 1st August 1821 with three hundred and forty pupils, of whom eighty needy boys and girls were provided with their uniforms.

“They used to be the other way round,” admitted Reg mischievously, indicating the pair of figures on the exterior, “their eyes used to meet but now they are looking in opposite directions.” Yet, given all the changes in the City in the last two centuries – “Who can blame the kids if their eyes are wandering now?” I thought. It was a sentiment with which Reg seemed in accord and which the enterprising Mrs Coade exemplified in the longevity of her endeavours too. “I should have retired years ago but I don’t like sitting indoors and couldn’t stand all that earlobe bashing,” he confessed to me, “I like to be outside doing something.”

In St Botolph’s Churchyard, Bishopsgate – Schoolroom and Sir William Rawlins’ tomb

Original figure coated in layers of paint

Modern replica now in place upon St Botolph’s Hall

Original figure coated in layers of paint

Modern replica now in place upon exterior of St Botolph’s Hall

With layers of paint removed, the original figures now stand inside the hall

Reg the Caretaker at St Botolph’s

Coade stone Nelson pediment at Greenwich

Archive photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

The Stepney School Strike

In the summer of 1971, eight hundred pupils went on strike in Stepney, demanding that their teacher, Chris Searle, be reinstated after the school fired him for publishing a book of their poetry. At a time of unrest, following strikes by postmen and dustmen, the children’s strike became national headline news and they received universal support in the press for their protest.

More than two years later, after the parents, the Inner London Education Authority, the National Union of Teachers, and even Margaret Thatcher, then Education Secretary, came out in favour of Chris Searle, he got his job back and the children were vindicated. And the book of verse, entitled “Stepney Words” sold more than fifteen thousand copies, with the poems published in newspapers, and broadcast on television and read at the Albert Hall. It was an inspirational moment that revealed the liberating power of poetry as a profound expression of the truth of human experience.

Many of those school children – in their sixties now – still recall the event with great affection as a formative moment that changed their lives forever, and so when Chris Searle, the twenty-four-year-old student teacher of 1971 returned to the East End to recall that cathartic summer and meet some of his former pupils, it was an understandably emotional occasion. And I was lucky enough to be there to hear what he had to say.

I grew up in the fifties and sixties, failed the eleven plus and I hated any kind of divisiveness in education, I saw hundreds of my mates just pushed out into menial jobs. So I got into a Libertarian frame of mind and became involved in Socialist politics. I was in the Caribbean at the time of the Black Power uprisings, so I had some fairly strong ideas about power and education. Sir John Cass Foundation & Redcoat School in Stepney was grim. It was a so-called Christian School and many of the teachers were priests, yet I remember one used to walk round with a cape and cane like something out of Dickens.

The ways of the school contrasted harshly with the vitality and verve of the students. As drama teacher, I used to do play readings but I found they responded better to poetry, and I was reading William Blake and Isaac Rosenberg to them, both London poets who took inspiration from the streets. So I took the pupils out onto the street and asked them to write about what they saw, and the poems these eleven-year-olds wrote were so beautiful, I was stunned and I thought they should be published. Blake and Rosenberg were published, why not these young writers? We asked the school governors but they said the poems were too gloomy, so they forbade us to publish them.

I showed the poems to Trevor Huddleston, the Bishop of Stepney, and he loved them. And it became evident that there was a duality in the church, because the chairman of the school governors who was a priest said to me, ‘“Don’t you realise these are fallen children?” in other words, they were of the devil. But Trevor Huddleston read the poems and then, with a profound look, said, “These children are the children of God.” So I should have realised there was going to be a bit of a battle.

There was even a suggestion that I had written the poems myself, but though I am a poet, I could not have written anything as powerful as these children had done. Once it was published, the sequence of events was swift, I was suspended and eight hundred children went on strike the next day, standing outside in the rain and refusing to go inside the school. I didn’t know they were going to go on strike, but the day before they were very secretive and I realised something was up, though I didn’t know what it was.

I didn’t have an easy time as a teacher, it was sometimes difficult to get their interest, and I had bad days and I had good days, and sometimes I had wonderful days. Looking back, it was the energy, and vitality, and extraordinary sense of humour of the children that got you through the day. And if, as a teacher, you could set these kids free, then you really did begin to enjoy the days. It gave me the impetus to remain a teacher for the rest of my life.

I tried to get the kids to go back into the school.

Tony Harcup, a former pupil of Chris Searle’s and now senior lecturer in Journalism at Sheffield University, spoke for many when he admitted, “It was one of the proudest days of my life, it taught me that you can make a stand. It was about dignified mutual respect. He didn’t expect the worst of us, he believed everyone could produce work of value. He opened your eyes to the world.”

During the two years Chris was waiting to be reinstated at the school, he founded a group of writers in the basement of St George’s Town Hall in Cable St. Students who had their work published in “Stepney Words” were able to continue their writing there, thinking of themselves as writers now rather than pupils. People of different ages came to join them, especially pensioners, and they used the money from “Stepney Words” to publish other works, beginning with the poetry of Stephen Hicks, the boxer poet, who lived near the school and had been befriended by many of children.

“Stepney Words” became the catalyst for an entire movement of community publishing in this country, and many involved went on to become writers or work in related professions.“The power to write, the power to create, and the power of the imagination, these are the fundamentals to achieve a satisfied life,” said Chris, speaking from the heart, “and when you look back today at the lives of those in the Basement Writers, you can see the proof of that.”

The story of the Stepney school strike reveals what happens when a single individual is able to unlock the creative potential of a group of people, who might otherwise be considered to be without prospects, and it also reminds us of all the human possibility that for the most part, remains untapped. ” I just want to thank the young people that stood up for me” declared Chris Searle with humility, thinking back over his life and recalling his experiences in Stepney, “How could you not be optimistic about youth when you were faced with that?”

Returning to the East End forty years after the school strike, teacher Chris Searle reads one of the original poems from Stepney Words,”Let it Flow, Joe.”, with some of his former pupils.

You might like to read about