In Search Of Roman London

Roman London is still under construction

From Spitalfields, you have only to walk down Bishopsgate to find yourself in Londinium, since the line of Bishopsgate St follows that of Ermine St which was the major Roman road north from London Bridge. Tombs once lined the path as it approached the City, just as they did along the Appian Way in Rome.

The essential plan of the City of London was laid out by the Romans when they built their wall around Londinium at the end of the second century, after Boudica and her tribes burnt the settlement. Eighty years earlier, the Romans had constructed a fort where the Barbican stands today and, in their defensive plan, they extended its walls south to the Thames and in an easterly arc that met the river where the Tower of London stands now.

A fine eighteenth century statue of the Emperor Trajan touts to the tourists at Tower Hill, drawing their attention to the impressive stretch of wall that survives there, striped by the characteristic Roman feature of courses of red clay tiles, inserted between layers of shaped Kentish Ragstone to ensure that the wall would be consistently level.

Just fifty yards from here at Cooper’s Row, round the back of the Grange City Hotel, is an equally spectacular stretch of wall that is off the tourist trail. Here you can see the marks of former staircases and medieval windows cut through to create a rugged monument of significant height.

Yet, in the mile between here and the Barbican, very little has survived from the centuries in which stone from the wall was pillaged for other buildings. It is possible to seek access to some corporate premises with lone fragments marooned in the basement, but instead I decided to walk over to All Hallows by the Tower which has a little museum of great charisma in its crypt. Here is part of the tessellated floor of a Roman dwelling of the second century and Captain Lowther’s splendid model of Roman London from 1928.

At the Barbican, a stretch of wall that was once part of the Roman fort is visible, punctuated by a string of monumental bastions which are currently under restoration. Walking up from St Paul’s, you come across the wall in Noble St first, still encrusted with the bricks of the buildings within which it was once embedded. Then you arrive at London Wall, an avenue of gleaming towers lining a windy boulevard of fast-moving traffic, which takes it name from the ancient edifice.

I was lucky enough to be permitted access to a secret concrete bunker, beneath the road surface yet above the level of the underground car park. Here was one of the gateways of Roman London and I saw where the wooden gate posts had worn grooves into the stone that supported them. At last, I could enter Roman London. In that underground room, I walked across the few metres of gravel chips that now cover the ground level of the former roadway between the gate posts, where the chariots passed through. Long ago, I should have been trampled by the traffic if I had stood there, just as I should be mown down if I stood in London Wall today. We switched out the light and locked the door on Roman London to emerge into the daylight again.

In the gardens of the Barbican, the presence of foliage and grass permits the bastions of the City wall to assert themselves, standing apart from the contemporary built environment that surrounds them. From here, I turned west to visit the cloister of St Vedast in Foster Lane, which has an intriguing panel of a tessellated floor mounted in a frame, and St Bride’s in Fleet St, where deep in the crypt, you can lean over a wall to see the floor of the Roman dwelling that once stood there, reflected in a mirror. The reality of these items stirs the imagination just as their fragmentary nature challenges it to envisage such a remote world.

By now, it was late afternoon. I was weary and the sunshine had faded, and it was time to make tracks quickly back to Spitalfields as the sky clouded over – yet I was inspired by my brief Roman holiday in London.

Eighteenth century bronze statue of Trajan at Tower Hill

Model of Roman London in the crypt of All Hallows by the Tower. Made by Captain Lowther in 1928, it shows London Bridge AD 400 – Spitalfields appears as a settlement of Britons beyond the wall.

Roman City Wall at Tower Hill

At Tower Hill

At Cooper’s Row

Lines of red clay tiles were inserted between the blocks of stone to keep the wall level

Tessellated floor in the crypt of All Hallows by the Tower

Timber from a Roman wharf preserved in the porch of St Magnus the Martyr

In the cloister of St Vedast Alias Foster

In the crypt of St Bride’s, Fleet St

Foundation of a Roman Guard Tower in Noble St

Outside 1 London Wall

Part of the entrance gate to Roman London in the underground chamber

Model of the north west entrance to Roman London

A fragment of wall in the underground chamber

Bastion at London Wall

You might also like to read

Tex Adjetunmobi, Photographer

Bandele Ajetunmobi – widely known as Tex – took photographs in the East End for almost half a century, starting in the late forties. He recorded a tender vision of interracial cameraderie, notably as manifest in a glamorous underground nightlife culture yet sometimes underscored with melancholy too – creating poignant portraits that witness an almost-forgotten era of recent history.

In 1947, at twenty-six years old, he stowed away on a boat from Nigeria – where he found himself an outcast on account of the disability he acquired from polio as a child – and in East London he discovered the freedom to pursue his life’s passion for photography, not for money or reputation but for the love of it.

He was one of Britain’s first black photographers and he lived here in Commercial St, Spitalfields, yet most of his work was destroyed when he died in 1994 and, if his niece had not rescued a couple of hundred negatives from a skip, we should have no evidence of his breathtaking talent.

Fortunately, Tex’s photographs found a home at Autograph ABP where they are preserved in the permanent archive and it was there I met with Victoria Loughran, who had the brave insight to appreciate the quality of her uncle’s work and make it her mission to achieve recognition for him posthumously.

“He was the youngest brother and he was disabled as well but he was very good at art, so they apprenticed him to a portrait photographer in Lagos. It suited him yet it wasn’t enough, so he packed up and, without anything much, left for England with my Uncle Chris.

Juliana, my mum had already come from Nigeria and, when I was born, she lived in Brick Lane but, after a gas explosion, we had to move out – that’s how we ended up in Newham. When I was a child, we didn’t come over here much – except sometimes to visit Brick Lane and Petticoat Lane on a Sunday – because we had moved to a better place. I understood I was born in Bethnal Green but I grew up in a better class of neighbourhood.

I knew that she didn’t approve of my uncle’s lifestyle, she didn’t approve of the drinking and probably there were drugs too. They were lots of rifts and falling out that I didn’t understand at the time. When everything became about having jobs to survive, she couldn’t comprehend doing something which didn’t make money. In another life, she might have understood his ideals – but we were immigrants and you have to feed yourself. She thought, ‘Why are you doing something that doesn’t sit comfortably with being poor?’

He did all this photography yet he didn’t do it to make money, he did it for pleasure and for artistic purposes. He was doing it for art’s sake.He had lots of books of photography and he studied it. He was doing it because those things needed to be recorded. You fall in love with a medium and that’s what happened to him. He spent all his money on photography. He had expensive cameras, Hasselblads and Leicas. My mother said, ‘If you sold one, you could make a visit to Nigeria.’ But he never went back, he was probably a bit of an outcast because of his polio as a child and it suited him to be somewhere people didn’t judge him for that.

He used to come and visit regularly when we lived in Stratford and there are family pictures that he took of us. His pictures pop out at me and remind me of my childhood, they prove to me that it really was that colourful. He was fun. Cissy was his girlfriend, they were together. She was white. When Cissy separated from her husband, he got custody of her children because she was with a black man – and her family stopped talking to her. She and Tex really wanted to have children of their own but they weren’t able to. They were Uncle Tex and Aunty Cissy, they would come round with presents and sweets, and they were a model couple to us as children. To see a mixed race couple wasn’t strange to us – where we lived it was full of immigrants and we were poor people and we just got on with life, and helped each other out.

He used to do buying and selling from a stall in Brick Lane. When he died, they found so much stuff in his flat, art equipment, pens, old records and fountain pens. He had a very good eye for things. Everybody knew him, he was always with his camera and they stopped him in the street and asked him to take their picture. He was able to take photographs in clubs, so he must have been a trusted and respected figure. Even if the subjects are poor, they are strutting their stuff for the camera. He gave them their pride and I like that.

He was not extreme in his vices. He died of a heart attack after being for a night out with his card-playing friends. He lived alone by then, he and Cissy were separated. But he was able to go to his neighbour’s flat and they called an ambulance so, although he lived alone, he didn’t die alone.

I thought he deserved more, that he was important. I just got bloody-minded. It wasn’t just because he was my uncle, it’s because it was brilliant photography. He deserved for people to see his work. There were thousands of pictures but only about three hundred have survived. Just one plastic bag of photos from a life’s work.”

Tex was generous with his photographs, giving away many pictures taken for friends and acquaintances in the East End – so if anybody knows of the existence of any more of his photos please get in touch so that we may extend the slim yet precious canon of Bandele “Tex” Ajetunmobi’s photography.

Whitechapel night club, nineteen-fifties

East End, nineteen seventies

On Brick Lane, seventies

Bandele “Tex” Ajetunmobi, self portrait

On Liverpool St Station

When I was callow and new to London, I once arrived back on a train into Liverpool St Station after the last tube had gone and spent the night there waiting for the first tube next morning. With little money and unaware of the existence of night buses, I passed the long hours possessed by alternating fears of being abducted by a stranger or being arrested by the police for loitering. Liverpool St was quite a different place then, dark and sooty and diabolical – before it was rebuilt in 1990 to become the expansive glasshouse that we all know today – and I had such an intensely terrifying and exciting night then that I can remember it fondly now.

Old Liverpool St Station was both a labyrinth and the beast in the labyrinth too. There were so many tunnels twisting and turning that you felt you were entering the entrails of a monster and when you emerged onto the concourse it was as if you had arrived, like Jonah or Pinocchio, at the enormous ribbed belly.

I was travelling back from spending Saturday night in Cromer and stopped off at Norwich to explore, visiting the castle and studying its collection of watercolours by John Sell Cotman. It was only on the slow stopping-train between Norwich and London on Sunday evening that I realised my mistake and sat anxiously checking my wristwatch at each station, hoping that I would make it back in time. When the train pulled in to Liverpool St, I ran down the platform to the tube entrance only to discover the gates shut, closed early on Sunday night.

I was dressed for summer, and although it had been warm that day, the night was cold and I was ill-equipped for it. If there was a waiting room, in my shameful fear I was too intimidated to enter. Instead, I sat shivering on a bench in my thin white clothes clutching my bag, wide-eyed and timid as a mouse – alone in the centre of the empty dark station and with a wide berth of vacant space around me, so that I could, at least, see any potential threat approaching.

Dividing the station in two were huge ramps where postal lorries rattled up and down all night at great speed, driving right onto the platforms to deliver sacks of mail to the awaiting trains. In spite of the overarching vaulted roof, there was no sense of a single space as there is today, but rather a chaotic railway station criss-crossed by footbridges, extending beyond the corner of visibility with black arches receding indefinitely in the manner of Piranesi.

The night passed without any threat, although when the dawn came I felt as relieved as if I had experienced a spiritual ordeal, comparable to a night in a haunted house in the scary films that I loved so much at that time. It was my own vulnerability as an out-of-towner versus the terror of the unknowable Babylonian city, yet – if I had known then what I knew now – I could simply have walked down to the Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market and passed the night in one of the cafes there, safe in the nocturnal cocoon of market life.

Guilty, and eager to preserve the secret of my foolish vigil, I took the first tube to the office in West London where I worked then and changed my clothes in a toilet cubicle, arriving at my desk hours before anyone else.

Only the vaulted roof and the Great Eastern Hotel were kept in the dramatic transformation that created the modern station, sandwiched between new developments, and the dark cathedral where I spent the night is gone. Yet a magnetism constantly draws me back to Liverpool St, not simply to walk through, but to spend time wondering at the epic drama of life in this vast terminus where a flooding current of humanity courses through twice a day – one of the great spectacles of our extraordinary metropolis.

Shortly after my night on the station experience, I got a job at the Bishopsgate Institute – and Liverpool St and Spitalfields became familiar, accessed through the tunnels that extended beyond the station under the road, delivering me directly to my workplace. I noticed the other day that the entrance to the tunnel remains on the Spitalfields side of Bishopsgate, though bricked up now. And I wondered sentimentally, almost longingly, if I could get into it, could I emerge into the old Liverpool St Station, and visit the haunted memory of my own past?

A brick relief of a steam train upon the rear of the Great Eastern Hotel.

Liverpool St Station is built on the site of the Bethlehem Hospital, commonly known as “Bedlam.”

Archive images copyright © Bishopsgate Institute

Cockney Beanos

A beano from Stepney in the twenties (courtesy Irene Sheath)

We have reached that time of year when a certain clamminess prevails in the city and East Enders turn restless, yearning for a trip to the sea or at the very least an excursion to glimpse some green fields. In the last century, pubs, workplaces and clubs organised annual summer beanos, which gave everyone the opportunity to pile into a coach and enjoy a day out, usually with liberal opportunity for refreshment and sing-songs on the way home.

Ladies’ beano from The Globe in Hartley St, Bethnal Green, in the fifties. Chris Dixon, who submitted the picture, recognises his grandmother, Flo Beazley, furthest left in the front row beside her next door neighbour Flo Wheeler, who had a fruit and vegetable stall on Green St. (courtesy Chris Dixon)

Another beano from the fifties – eighth from the left is Jim Tyrrell (1908-1991) who worked at Stepney Power Station in Limehouse and drank at the Rainbow on the Highway in Ratcliff.

Mid-twentieth century beano from the archive of Britton’s Coaches in Cable St. (courtesy Martin Harris)

Beano from the Rhodeswell Stores, Rhodeswell Rd, Limehouse in the mid-twenties.

Taken on the way to Southend, this is a ladies’ beano from The Beehive in the Roman Rd during the fifties or sixties in a coach from Empress Coaches. The only men in the photo are the driver and the accordionist. Joan Lord (née Collins) who submitted the photo is the daughter of the publicans of The Beehive. (Courtesy Joan Lord)

Terrie Conway Driver, who submitted this picture of a beano from The Duke of Gloucester, Seabright St, Bethnal Green, points out that her grandfather is seventh from the left in the back row. (Courtesy Terrie Conway Driver)

Taken on the way to Southend, this is a men’s beano from The Beehive in the Roman Rd in the fifties or sixties in a coach from Empress Coaches. (Courtesy Joan Lord)

Beano in the twenties from the Victory Public House in Ben Jonson Rd, on the corner with Carr St. Note the charabanc – the name derives from the French char à bancs (“carriage with wooden benches”) and they were originally horse-drawn.

A crowd gathers before a beano from The Queens’ Head in Chicksand St in the early fifties. John Charlton who submitted the photograph pointed out his grandfather George standing in the flat cap holding a bottle of beer on the right with John’s father Bill on the left of him, while John stands directly in front of the man in the straw hat. (Courtesy John Charlton)

Beano for Stepney Borough Council workers in the mid-twentieth century. (Courtesy Susan Armstrong)

Martin Harris, who submitted this picture, indicated that the driver, standing second from the left, is Teddy Britton, his second cousin. (Courtesy Martin Harris)

In the Panama hat is Ted Marks who owned the fish place at the side of the Martin Frobisher School, and is seen here taking his staff out on their annual beano.

George, the father of Colin Watson who submitted this photo, is among those who went on this beano from the Taylor Walker brewery in Limehouse. (Courtesy Colin Watson)

Pub beano setting out for Margate or Southend. (Courtesy John McCarthy)

Men’s beano from c. 1960 (courtesy Cathy Cocline)

Late sixties or early seventies ladies’ beano organised by the Locksley Estate Tenants Association in Limehouse, leaving from outside The Prince Alfred in Locksley St.

The father of John McCarthy, who submitted this photo, is on the far right squatting down with a beer in his hand, in this beano photo taken in the early sixties, which may be from his local, The Shakespeare in Bethnal Green Rd. Equally, it could be a works’ outing, as he was a dustman working for Bethnal Green Council. Typically, the men are wearing button holes and an accordionist accompanies them. Accordionists earned a fortune every summer weekend, playing at beanos. (courtesy John McCarthy)

John Sheehan, who submitted this picture, remembers it was taken on a beano to Clacton in the sixties. From left to right, you can seee John Driscoll who lived in Grosvenor Buildings, Dan Daley of Constant House, outsider Johnny Gamm from Hackney, alongside his cousin, John Sheehan from Constant House and Bill Britton from Holmsdale House. (Courtesy John Sheehan)

Images courtesy Tower Hamlets Community Homes

You may also like to read about

Thomas Onwhyn’s Pictures Of London

Born in Clerkenwell in 1813, as the eldest son of a bookseller, Thomas Onwhyn created a series of cheap mass-produced satirical prints illustrating the comedy of everyday life for publishers Rock Brothers & Payne in the eighteen forties and fifties. In his time, Onwhyn was overshadowed by the talent of George Cruickshank and won notoriety for supplying pictures to pirated editions of Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby, which drew the ire of Charles Dickens who wrote of, “the singular Vileness of the Illustrations.”

Nevertheless, these fascinating ‘Pictures of London’ from Bishopsgate Institute demonstrate a critical intelligence, a sly humour and an unexpected political sensibility. In this social panorama,originally published as one concertina-fold strip, Onwhyn contrasts the culture and lives of rich and the poor in London with subtle comedy, tracing their interdependence yet making it quite clear where his sympathy lay.

The Court – Dress Wearers.

Dressmakers.

The Opera Box.

The Gallery.

The West End Dinner Party.

A Charity Dinner.

Mayfair.

Rag Fair.

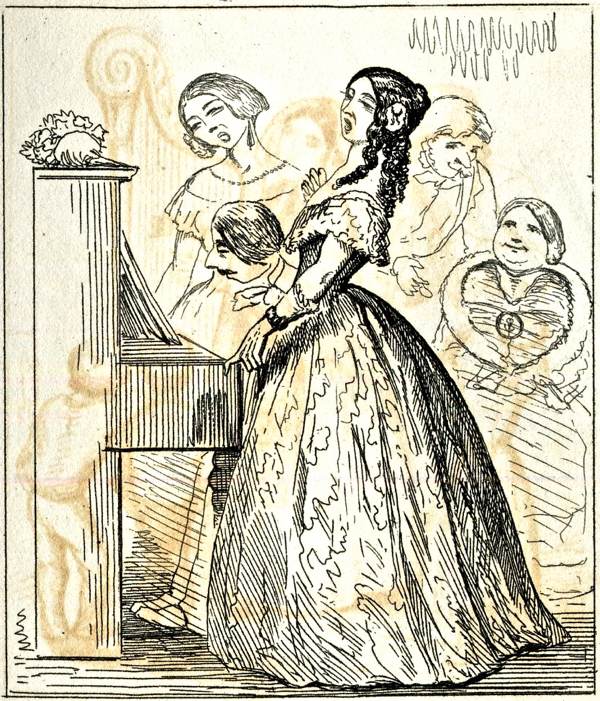

Music of the Drawing Room.

Street Music.

The Physician.

The Medical Student.

The Parks – Day.

The Parks – Night.

The Club – The Wine Bibber.

The Gin Shop – The Dram Drinker.

The Shopkeeper.

The Shirtmaker.

The Bouquet Maker.

The Basket Woman. (Initialled – T.O. Thomas Onwhyn)

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Roman Ruin At The Hairdresser

Nicholson & Griffin, Hairdresser & Barber

The reasons why people go the hairdresser are various and complex – but Jane Sidell, Inspector of Ancient Monuments, and I visited a salon in the City of London for a purpose quite beyond the usual.

There is a hairdresser in Gracechurch St at the entrance to Leadenhall Market that is like no other. It appears unremarkable until you step through the tiny salon with room only for one customer and descend the staircase to find yourself in an enormous basement lined with mirrors and chairs, where busy hairdressers tend their clients’ coiffure.

At the far corner of this chamber, there is a discreet glass door which leads to another space entirely. Upon first sight, there is undefined darkness on the other side of the door, as if it opened upon the infinite universe of space and time. At the centre, sits an ancient structure of stone and brick. You are standing at ground level of Roman London and purpose of the visit is to inspect this fragmentary ruin of the basilica and forum built here in the first century and uncovered in 1881.

Once the largest building in Europe north of the Alps, the structure originally extended as far west as Cornhill, as far north as Leadenhall St, as far east as Lime St and as far south as Lombard St. The basilica was the location of judicial and financial administration while the forum served as a public meeting place and market. With astonishing continuity, two millennia later, the Roman ruins lie beneath Leadenhall Market and the surrounding offices of today’s legal and financial industries.

In the dark vault beneath the salon, you confront a neatly-constructed piece of wall consisting of fifteen courses of locally-made square clay bricks sitting upon a footing of shaped sandstone. Clay bricks were commonly included to mark string courses, such as you may find in the Roman City wall but this usage as an architectural feature is unusual, suggesting it is a piece of design rather than mere utility.

Once upon a time, countless people walked from the forum into the basilica and noticed this layer of bricks at the base of the wall which eventually became so familiar as to be invisible. They did not expect anyone in future to gaze in awe at this fragment from the deep recess of the past, any more than we might imagine a random section of the city of our own time being scrutinised by those yet to come, when we have long departed and London has been erased.

Yet there will have been hairdressers in the Roman forum and this essential human requirement is unlikely ever to be redundant, which left me wondering if, in this instance, the continuum of history resides in the human activity in the salon as much as in the ruin beneath it.

You may also like to read about

Terry Scales, Painter

Terry Scales

Terry Scales has lived for more than fifty years in a quiet back street in a forgotten corner of Greenwich where the tourists do not stray. To find him, I wandered through narrow thoroughfares between modest old terraces that splayed off at different angles with eccentric geometry, just like lines upon a protractor, to reach the park at zero degrees Longitude.

In the front room, Terry’s wife, Cristiana Angelini, was painting and he ushered me past. “She has the best room, but I have the best light,” He whispered with a sly grin as he led me quickly into his crowded studio overlooking the garden. There, among a proliferation of handsome pictures of boats upon the Thames that are his forte, Terry showed me the first oil painting that he did at art school – an accomplished still life in the manner of Cezanne – and a fine pencil drawing of him in his teens by Susan Einzeg. A portrait that is recognisable seventy years later on account of Terry’s distinctively crooked aquiline nose and feverish youthful energy.

I know of no other painter so well placed to paint scenes of the Thames as Terry Scales since, alongside his natural facility with the brush, he is able to draw upon a lifetime’s experience, growing up in a family that made its living upon the river for generations and then working in the Docks himself. “Because of the strikes, people think that dockers were all muscle and brawn, but we had men who left solicitors’ offices to work in Docks. It has to do with the independent lifestyle, you were never working for just one company, you were working all over the shop.” Terry assured me, eager to dispel the notion of dockers as an unsophisticated workforce, “Among that vast body of men, there were many very talented people.”

“They discovered I was a professionally trained artist and asked me to draw portraits,” he revealed, showing me his work for the National Dock Labour Board magazine in the fifties, “but my senior colleagues were very suspicious and conservative. I grew a beard after two years in the Docks and they were all scandalised!”

Terry’s work is the outcome of an intimate relationship with his subject, both the working life of the river and its shifting climate. “Most of the subjects of my paintings have gone now,” he confessed, casting his eyes fondly around the gallery of maritime scenes that surrounded us, evoking the vanished world of the Docks with such vibrant presence. I was fascinated to learn how Terry had combined his employment as a docker with his artistic endeavour – so that each fed the other – and he obliged by telling me the whole story.

“I was born in 1932 in St Olave’s, Rotherhithe, and my family lived in that area for as long as anyone knew. My mother’s people came over from Ireland in the eighteen-fifties after the potato famine, and they were called O’Driscoll which they changed to Driscoll. On both sides, my family worked in the Docks, and my father was a ganger in the Albert Docks and a lighterman. A hundred years ago, they were very adventurous, with my grandfather travelling to Australia and America, taking ships here and there, and picking up work. On my father’s side, they were all dockers in Bermondsey working on the grain wharfs near Cherry Gardens Pier – the lightermen’s stopping point where they changed barges.

I was evacuated to Seaton in the West Country which opened my eyes to the splendour of landscape and I returned after the war with a broad Devon accent to live in one of the prefab villages in Bermondsey. After a good schooling in Devon, I was sent to school in Rotherhithe which was appalling – there was a complete lack of discipline and I learnt absolutely nothing. The Labour government brought in a scheme where pupils that were talented but not academic could go to a college and learn a craft. So, at the age of thirteen, I applied to Camberwell School of Art and was accepted. And when I arrived there it was like heaven, because we had the best painters in England teaching us and, being thirteen I took it very seriously indeed – there was Victor Pasmore, Keith Vaughan, John Minton, William Coldstream and members of the Euston Rd Group.

I think the teachers must have appreciated that I was such a serious student because, by the age of sixteen, I had sold paintings to all the staff and William Coldstream bought a canal scene of mine. So I was doing very well as a student artist. Keith Vaughan, John Minton and Susan Einzig, they were the Neo-Romantic group and they took me under their wing. But the members of the Euston Rd Group taught me to draw because they were keen on observation, so I owe my drawing ability to them. There was an ideological war going on between their subdued English Realism and the Neo-Romantics who were influenced by Picasso and Matisse.

I was the youngest in my year and, when we graduated in 1952, I had to do National Service so I applied to the RAF. A Jazz musician called Monty Sunshine told me I should be a telephonist because it was the cushiest job. So I applied to do signals in the Far East, but they sent me to work at East India Docks and I was able to live at home. By the time I was demobbed all my friends were teaching, but I didn’t fancy that, as I was only twenty-one, so I took a job at a publicity studio in Fleet St that did posters for Hollywood films and I became a background artist. Once, I painted a brooding sky with lightning as the background to the poster for ‘The Night My Number Came Up’ but after they had put a great big aeroplane on it, and the stars’ faces, and the title, you could hardly see any of my work! I was paid a very low wage, the painters who did the stars’ faces got the top money with the lettering artists below them, so I realised it would be a long time before I earned any money.

I was ambitious, so my father said to me, ‘This is peanuts – why don’t you come and work in the Docks? You could build up your bank balance.’ In 1955, I took a docker’s brief at number one sector, Surrey Docks, and over a five year period I worked every wharf from Tower Bridge to Woolwich. In the summer, once the Baltic Sea thawed, I worked on the timber ships. They came with huge cargoes and every strip had to be manhandled into barges. I worked quite hard, earned very good wages and had no accidents.

One day, I finished early after unloading a ship of Belgian chocolates, so I decided to go over to Camberwell and see my old teachers. I dropped in on the Foundation Course and they said, ‘Thank God you’ve turned up because one of the tutors has been taken ill! Can you take the class?’ And afterwards, they said, ‘Can you come back tomorrow?’ Prior to that, I had an exhibition at the South London Gallery and I continued painting while I was working at the Docks. I painted a whole exhibition once during an eight week strike.

I knew the Welfare Officer at the Surrey Docks and I said, ‘I’m going to leave to teach.’ He said, ‘Teaching is a very insecure profession, you shouldn’t give up the Docks.’ But the Docks closed ten years later and I stayed teaching at Camberwell in the Fine Art Department for the next thirty years, until I retired in 1990 to concentrate on my own work.

The appeal of painting the Thames for me is not just because of my personal background, but because the river has space. In London, you are aware of being closed in yet when you see the Thames it has a grandeur, and when the tall ships are there you feel the magnificence of it. You get changes of light and, although I’ve often been prevented from finishing paintings because of surprises, like breaks in the weather or the sudden appearance of smoke, it always adds something. You start to paint a ship on a Monday, it rains on a Tuesday and it’s a different ship there on the Thursday – but if you are a landscape artist seeking qualities of light, ambiguity has to be part of it.”

Terry in his studio, sitting with the first painting he ever did at art school. “A man who paints puts his heart on the wall and in that painting is the man’s life” – John Minton, 1951.

Bert and James, Barges, Prior’s Wharf, 1990

Hungerford Bridge

View from the Festival Hall

Pier at Bankside

Red Tug passing St Paul’s

Shipping off Piper’s Wharf, 1983

Greenwich Peninsula.

The ‘John Mackay,’ Trans-Atlantic Cable Layer, Enderby’s Wharf, 1979

Mike Canty’s Boat Yard, 1988

Terry with his shed that he constructed entirely out of driftwood from the Thames.

Paintings and drawings copyright © Terry Scales