On Night Patrol With Lew Tassell

Meanwhile, you can join me on an atmospheric autumn walk through the streets of Spitalfields. Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Police Constable Lew Tassell of the City of London Police

“One week in December 1972, I was on night duty. Normally, I would be on beat patrol from Bishopsgate Police Station between 11pm-7am. But that week I was on the utility van which operated between 10pm-6am, so there would be cover during the changeover times for the three City of London Police divisions – Bishopsgate, Wood St and Snow Hill. One constable from each division would be on the van with a sergeant and a driver from the garage.

That night, I was dropped off on the Embankment during a break to allow me to take some photographs and I walked back to Wood St Police Station to rejoin the van crew. You can follow the route in my photographs.

The City of London at night was a peaceful place to walk, apart from the parts that operated twenty-four hours a day – the newspaper printshops in Fleet Street, Smithfield Meat Market, Billingsgate Fish Market and Spitalfields Fruit & Vegetable Market.

Micks Cafe in Fleet St never had an apostrophe on the sign or acute accent on the ‘e.’ It was a cramped greasy spoon that opened twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. During the night and early morning it served print-workers, drunks returning from the West End and the occasional vagrant.

Generally, we police did not use it. We might have been unwelcome because we would have stood out like a sore thumb. But I did observation in there in plain clothes sometimes. Micks Cafe was a place where virtually anything could be sourced, especially at night when nowhere else was open.”

Lew Tassell

Middle Temple Lane

Pump Court, Temple

King’s Bench Walk, Temple

Bouverie St, News of the World and The Sun

Fleet St looking East towards Ludgate Circus

Ludgate Hill looking towards Fleet St under Blackfriars Railway Bridge, demolished in 1990

Old Bailey from Newgate St looking south

Looking north from Newgate St along Giltspur St, St Bartholomew’s Hospital

Newgate St looking towards junction of Cheapside and New Change – buildings now demolished

Cheapside looking east from the corner of Wood St towards St Mary Le Bow and the Bank

HMS Chrysanthemum, Embankment

Constable Lew Tassell, 1972

Photographs copyright © Lew Tassell

You may also like to take a look at

The Mind Keeps The Score

Let me take you on an atmospheric autumn walk through the streets of Spitalfields

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Andy Strowman

ANDY STROWMAN is hosting a poetry reading with fellow East End writers at House of Annetta, 25 Princelet St at 3pm on Sunday 30th October. Writers include Shamim Azad, Paul Collins, Jeffrey Kleinman, Roger Mills, Farah Naz, Milton Rahman, Ian Saville and Jamie Strowman.

The event is entitled THE MIND KEEPS THE SCORE, Remembering our past, honouring our future in stories and poems.

All are welcome, admission is free and no booking is required.

Let me introduce Andy Strowman, the poet of Stepney. ‘I’ve kept quiet for long periods of my life,’ Andy confessed to me when I met him recently. ‘I hope this interview will help people not to be ashamed and feel able to talk about whatever subject they want in life.’ Of modest yet charismatic demeanour, Andy is a born storyteller and I was rapt by his tale, unsentimental yet full of human sympathy too.

‘At Bearsted Maternity Hospital in Stoke Newington, the doctors said to my mother, ‘I’m sorry Mrs Strowman, you’re going to have to have a caesarean.’ But she said, ”Oh no you won’t’ and I gave one push and out you came.’ She showed formidable East End spirit. They brought me back to Milward St, where we lived at the back of the Royal London Hospital, one of the oldest streets in Whitechapel.

Rose, my mother – maiden name Cohen – was a true East Ender born at the Royal London Hospital. Her sister, my Aunty Rae, lived with us. Her brother Jack worked at the Cumberland Hotel where he introduced me to Mohammed Ali. Then there was Barney who was also a formidable, beautiful man. He ended up in Wormwood Scrubs because he was a Conscientious Objector. He was in the army but he had no bad bones in his body and refused to fight.

My mother started work at fourteen years old, her first job was in Whitechapel Rd at the junction with New Rd. She was besotted with wanting to be a milliner. She always stood up for herself and, in another generation, she would have been a Suffragette. In her first job, the governor told her to clean the toilets so she went home and told my grandmother.

My grandmother told the governor, ‘I sent my daughter here to get a training and learn a trade, she’s not here to clean toilets.’ He said, ‘But that’s how I started…’ So my grandmother told him, ‘My daughter’s not going to be working for you any more,’ and took her away. God bless her for fighting for her rights! My mother got another job and went up to the West End, copying designs for hats, then making them at home before taking them into her new work place where the manager was very pleased.

Her mother came from Vilna which was then in Russia, escaping the pogroms, the mass slaughter of Jews. She was fourteen when she came over and seventeen when she married. It was an arranged marriage to my grandfather, who was nineteen. He was from Warsaw, most likely the Vola district, and he was in the garment trade.

Sam, my father, was an American who became a black cab driver in London. His parents were Russian, from the Ukraine, who landed in New York. He came over here as a soldier in the Second World War and my mother met him in a night club in Piccadilly Circus. They got married in Philpot St Synagogue in Whitechapel, where I and my brothers had our Bar Mitzvahs.

It is emotional for me to talk about my childhood, because although there were many happy moments there were also many very sad ones. It still stays with me now and it is why I do everything I can to help other people.

There was an expectation that we would go out and play in the street to give our parents a break and we used to play football. We were often tasked with running errands for old people and my mum used to arrange for me to sit with old people in their houses too.

Next door lived Rosie Botcher. Mum and Betty Gillard used to go round and wash her down after she had cancer. When I was born, she was given a year to live but lived another thirteen years. Also in our street was Byla Kahn who was from Poland, I used to love to sit with her because she told me stories. Since I was always a good boy, I waited for that formidable moment when she pulled open a little drawer and produced a bar of Cadbury’s chocolate for me.

One of the stories she told me was about when she was living with her grandparents. One day, she was washing clothes in the river when a resplendent man came along on a horse. He climbed off and started to talk to her. He was beautifully dressed and had a sabre. When she got home and told her grandmother what had happened, her grandmother was furious. That man was a Cossack and they had a terrible reputation for violence against Jewish people.

I have so many memories of Milward St but, like so many good things, it came to an end. We got a letter and my brother Paul, the journalist, read at it and said, ‘We’re going to have to leave.’ By that time, my mum and dad had split up. My father left when I was fourteen and I did not see or hear from him again for nearly seven years. After he left my mother stayed in bed for year and gave up washing. The letter said the houses were ‘unfit for human habitation.’ I did not understand what it meant but my brother told me, ‘We can’t live here anymore.’

We moved to a maisonette in Wager St off Bow Common Lane but we missed the strong community in Milward St where neighbours helped each other. My uncle told me that on a Friday night, before the war, people would go out into the street and talk until one o’clock in the morning. He said that once the war came, people did not do it anymore and the habit never returned afterwards.

Primary school was an adventure for me. I was always the last one in and the first one out. I think I got it from my mother, she was born with a club foot and did not like school because the children used to make fun of her, so she had to leave school after everyone else had gone home.

However I made a lot of good friends at Robert Montefiore School in Hanbury St. My favourite memory is when I was late and got taken upstairs and put into the class room by my mum. She asked ‘Where’s Mr Martin?’ and one of the children said, ‘He’s gone out.’ So she went to the front and announced, ‘I’m going to take the class now – everybody be quiet.’ As you can imagine, I was embarrassed to the hilt but also secretly proud that my mum with so little education had become a teacher. She asked, ‘Anybody going on holiday this year?’ One by one, they announced where they were going to go. Then Mr Martin returned in an advanced state of intoxication and said, ‘Well done, Mrs Strowman, you’re doing a marvellous job, you’d make a great teacher.’

We all had to take the 11-plus exam before we went to a grammar school or a secondary school but we never told our mums. Four of us – Colin McGraw, Keith Britten, Stephen Jones and me – made this pact to sit near each other and fail the exam, so we would all end up in the same school. But, although they failed and stuck together, I got a place at a grammar school, Davenant School in Whitechapel.

There began the tumult of my life. If I had one wish, it would be to have left school at eleven. In the first week, I was completely sabotaged by what was going on. I could not cope or keep up, moving classrooms, and doing homework.

The Chemistry teacher had a formidable stance and a bellowing voice like a ship’s captain. I was beginning to shake in fear and he noticed that – he picked up on my anxiety. He dragged me along the floor by my jacket until we reached the blackboard, where he smashed me to the ground. I could not believe what was going on. He pulled me up and dragged me all the way back. The lesson continued. We were performing our first experiment, a test for hydrogen with a lighted splint. We were all working from textbooks and I was the only one to take it with me at the end of the class. He swore at me and smashed me against the wall with his fist. I was crying on the floor and my head was swollen. No charge was ever made against this man but I later discovered that he was well known for this kind of behaviour. The climate was fully acceptable for violence in that school.

The next day the headteacher pulled me out of class, took me to his office and said, ‘Strowman, you’ve got to learn to take the rough with the smooth. Now get back to class.’ From that moment onwards, my life was hell. Boys made fun of me and I was frightened most of the time, getting beatings off the other kids – sometimes four or five times a week. I had nobody to tell.

I asked to my brother, ‘Why didn’t you warn me?’ He told me, ‘They are all bad in there.’ He told me he was lining up outside the Art room once before class and heard this noise inside, so one of the boys opened the door to discover the headmaster and the Art teacher on the floor, punching each other.

The Geography teacher tried to make it kinder for me. He encouraged me to look beyond. ‘Look out the window and think of the real world,’ he said to me once.

Our English teacher gave the books out quickly and put his feet up on the desk. He would learn back in his chair, while a pupil read ‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin,’ and drink a half bottle of whisky right down at three o’clock in the afternoon. I got endeared to him quite quickly. On my way back to school after lunch at home, I would see him come out of the Blackboard pub and steer him across Valance Rd and back into school.

Eventually, I was put in a separate class with eight others – two of whom were known to the police – and we did not have to do homework. School was very damaging for me. I received an apology from the deputy headteacher, forty-eight years later.

The sun only began to come out when writing came into my life – it happened for two reasons. I had a teacher who encouraged me to write poetry and my brother Paul became a journalist, he was an inspiration to me. When I came back from school after the beatings and the taunts at fourteen years old, I found reading poetry was a great release – I wanted to change my name to W B Yeats! He was my hero, also Dylan Thomas, John Keats, Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg – also the Yiddish writers. These people inspired me. Without money coming in, like a lot of East End boys, I lived on my wits – so I used to dodge my fare to buy books.

After I had left school, when I was sixteen and a half, I met Becky who was from California at Liverpool St Station, where I used to go in the evenings as write my poetry. I wrote her a poem.

To this day, when I write, I cannot believe it is me. It was a passion. It was the way out for me. Suddenly I learnt I could express myself. For around a year and a half, I was wandering around trying to get someone to take on my poetry. I visited publishers but got nowhere.

In the end somebody said to me, ‘Why don’t you try Chris Searle?’ He was the Stepney English teacher whose pupils went on strike after he was sacked. So went to a phone box in Aldgate by Gardiner’s Corner to call him and he said, ‘Why don’t you come round this evening?’ He became like a surrogate father to me. He recognised my work and helped publish STORY OF A STEPNEY BOY. He opened this magic door and I could go through it.

Poetry elevated my spirit and helped me to see myself more objectively. It took the thorns out of my soul.’

Andy, aged seven

Andy with his mother at the seaside

Andy aged eleven, with his parents

Uncle Davey

Uncle Jack once introduced Andy to Mohammed Ali

Andy’s father with Uncles, Davey and Jack

After Andy’s brother Howard’s Bar Mitzvah – Andy sits front left

Andy’s maternal grandmother

Aunty Rae

The wedding of Andy’s maternal grandparents

Copies of STORY OF A STEPNEY BOY may be obtained direct from Andy Strowman by emailing andy.strowman1@gmail.com

You may also like to read about

Dr Margaret Clegg, Keeper Of Human Remains

Enjoy an atmospheric autumn walk through Spitalfields

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

“They were once living, breathing people – they are you.”

In Spitalfields, people often talk of the human remains that were removed from the crypt – nearly a thousand bodies that were once packed in tight during the eighteenth century, safe from resurrectionists and on their way to eternal bliss.

During the nineteen-eighties, they were exhumed and transferred to the Natural History Museum where they rest today under the supervision of Dr Margaret Clegg, Head of the Human Remains Unit, who guards them both with loving attention and scholarly rigour, unravelling the stories that these long-ago residents of Spitalfields have to tell us about the quality of their lives and the nature of the human species.

“From the very first lecture I attended on the subject as an undergraduate, I became fascinated by what human remains can tell us about ourselves,” Dr Clegg admitted to me enthusiastically, “You can’t help but feel some kind of relationship when you are working with them. They were once living, breathing people – they are you.”

Dr Clegg led me through the vast cathedral-like museum and we negotiated the swarming mass of humanity that crowded the galleries on that morning, until we entered a private door into the dusty netherworld where the lights were dimmer and the atmosphere was calm.

“Dr Theya Mollison did the original excavation of the remains in the nineteen-eighties. There were more than nine hundred and for about half we know their age, sex, and when they were born and when they died, from the coffin plates. After they were removed, the remains were brought here to the Natural History Museum for longer-term analysis and study of the effects of occupation and the types of diseases they suffered. We had a large amount of information and could tell who was related to who. We could also tell who died in childbirth, and we have juveniles so we got information on childhood mortality and the funerary practices for children and babies, for example.

We have a special store for human remains at the museum, where each individual is stored in a separate box – it’s primarily bones but some have fingernails and hair. Any bodies that had been preserved were cremated when they were exhumed. The museum applied for a faculty from the Diocese of London to store the bones, the remains are not part of our permanent collection. The first faculty was for ten years and over time a second and third faculty were granted, but this will be the final one during which a decision will be made about the final disposition of the bones. During these years, the bones have been studied intensively. They are quite rare, there are very few such collections in which we know the age and sex of so many. They are probably our most visited and most researched collection. We have our own internal research and visiting researchers come from all over the world – for a wide variety of research purposes, including important work in forensics and evolutionary studies.

I am by training a biological anthropologist, and I am interested in the study of human archaeological remains from the perspective of how they grew and developed and what that can tell us about them.

In Spitalfields, you can compare families of the same age – one that ages quickly and one that ages slowly, which tells us something about the variables when we try to calibrate the date of remains at other sites. You can’t always tell what they did but you can tell, for example, that they used their upper body or that they developed muscles in their arms or legs as a direct result of their occupation. My dad was a printer and when he started out he used a hand press and developed a muscle in his arm as a consequence of using it. He’s seventy-nine and it’s still there. In those days, people started work at twelve or thirteen while the muscles were still developing and these traits quickly became established based upon their occupation. They were the ordinary working people of eighteenth century Spitalfields.

We get half a dozen emails a year from families who want to know if their ancestor who was buried in Christ Church is in the collection, but often I can’t help because they were buried in the churchyard or another part of the church. Occasionally, relatives ask if they can come and see them.”

Bonnet collected during excavations at Christ Church.

Shroud collected during excavations at Christ Church.

Cotton winding sheet collected during excavations at Christ Church.

Gold lower denture formed from a sheet of gold which was cut and folded around the lower molars.

Medicine bottle found in a child’s coffin during excavations at Christ Church.

Archaeological excavations in the crypt of Christ Church, Spitalfields, London, 1984-1986.

Excavation images © Natural History Museum

Portrait of Dr Clegg © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Daniele Lamarche’s East End

Enjoy an atmospheric autumn walk through the dusk in Spitalfields

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Cheshire St Doorway – “He once ran after me into the beigel shop and urged me to follow him. I had no idea what he wanted, but he led me back to my car on Bethnal Green Rd to show me that I’d left my keys in the door – he was desperately worried I would lose them. It made me chuckle after that when passers-by clutched their shoulder-bags firmly and crossed the street at the sight of him.”

Photographer Daniele Lamarche came to stay in a flat in Wentworth St for two weeks in 1981 and ended up staying on for years. Working as an international news scriptwriter for Independent Television News in Leadenhall St, Daniele first visited Brick Lane when the Indian correspondent brought her here for lunch and she was capitivated. “As you crossed Middlesex St, coming from the City of London, all the windows were smashed and things were desolate.” she recalled, yet for Daniele it was the beginning of a fascination explored through photography which continues until the present day. “I found it interesting that a lot of people would not come and visit me in East London,” she confided to me, “Because it was the first place I found in London with a sense of wonder, a sense of poetry.”

In 1982, Daniele began taking photographs in Brick Lane. It was a time of racial discord in the East End and, working for the GLC Race & Housing Action Team, Daniele employed her photography to record injuries inflicted upon victims of racial assault, the racist graffiti and the damage that was enacted upon the homes of immigrants, the broken windows and the burnt-out flats. “People actually spat at me and shouted at me in the street,” she confessed. Undeterred, Daniele became part of the Bengali community and was called upon to photograph poor living conditions as residents campaigned for better housing – with the outcome that she was also invited to record more joyful occasions too, weddings and community events.

A Californian of French/American ancestry who grew up in Argentina and was taught to ride by a Gaucho, Daniele found herself in her element working at the Spitalfields City Farm for several years where she kept dray horses and rode around the East End in a cart. An experience which afforded the unlikely observation that the lettered fascias on shops and street signs are placed high because they were originally designed to be at eye-level for those sitting in horse-drawn vehicles. Becoming embedded in Spitalfields, Daniele photographed many of the demonstrations and conflicts between Anti-Fascist and Racist groups that happened in Brick Lane, taking pictures for local and national newspapers, as well as building up a body of personal work which traces her intimate relationship with the people here, reflecting the trust and acceptance she won from those whom she met.

George, Nora & the Pigeon Cage – “East Enders who once cared for the ravens at the Tower of London, they soon took to raising racing pigeons for club meetings and competitions.”

Bethnal Green Pensioner – “A delicately-faced woman answered the door when I knocked and talked to me at length about her life, her dreams and her memories…”

Elections – “A group of Bengali women vote in 1992 – when the BNP stood in Tower Hamlets – many for the first time, following a drive made by groups including ‘Women Unite Against Racism.’ This was formed when local women found themselves to be three or four in meetings of over a hundred men and decided that, rather than be patronized as token females, they preferred to reach out to empower and support those women who might not otherwise vote.”

Eva wins the prize – “Eva came from Germany in the fifties, and grew plants and made soups out of what others might consider weeds – nettles, spinach, beet root tops – as well as sewing and embroidering all manners of pillows and textile pieces, from hop-pillows to aid sleep at night to tablecloths in the Richelieu style – and she was always game to show her wares of jams, sewing and plants at local events.”

French waiter in the docklands.

John & John – “This is John Lee, formerly of Spitalfields City Farm, now an organic dairy and pig co-operative farmer in Normandy, and ‘John’ who would often pop in to visit from Brick Lane Market and use the toilet.”

Immigration – “This refers to the moment when individuals of Asian origin in East Africa were told their colonial British passports would be no longer valid after a certain date – thus causing many to come to Britain to establish their rights to nationality, and as a result, many families camped out at the airport waiting to be met.”

Toy Museum Lascars – “a set of nineteenth century figures which represent seamen from a range of ethnicities and cultures who would have once been seen in the docklands.”

Lam at Fire – “Lam who worked for the GLC’s Race and Housing Action Team visits a family of Vietnamese heritage in 1984 in the Isle of Dogs after they were petrol bombed the night before and only saved because the granny awoke and saw smoke. Lam lived as a refugee in Hong Kong, and then in England where he was housed at first in a small village which greeted him with a gift of dog faeces through the letter box. ‘Is it the same in the USA?’ he asked me.”

Minicab – “A traditional minicab sign hovers over a resident whose front door, back door and side doors touched three different boroughs, causing him havoc and much correspondence with council tax officers.”

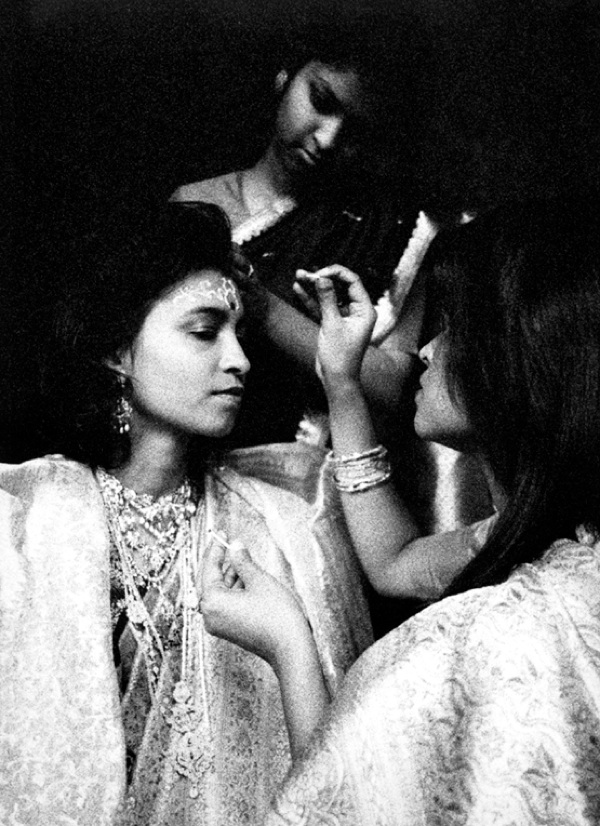

“Noore’s sister-in-law and friends help with wedding preparations, and a spot of toothpaste for intricate designs on her forehead.”

Paula, Woodcarver in her studio.

“Peter’s trades ranged from wheeling an old cart around as a rag & bone man to performing Punch & Judy puppet shows at children’s parties. Furniture and objects of interest flowed through his flat, and overflowed into the courtyard when a boat, which he’d sit in for evening cocktails, wouldn’t fit through the front door….”

Salmon Lane Horses – “A girl and her mother wait for the farrier after returning from school. Stables with horses for work and leisure dotted the streets and yards until developers picked off the remainder of the wasteland and yards where the animals were housed.”

Somali Girl – “This shows one of a group of children playing in a courtyard off Cable St where homes backed onto one another, enabling children to play within sight and ear-reach of parents indoors.”

Vietnamese Baby – “A voluntary sector advocate visits a Vietnamese family to check on their newborn’s progress. Over five hundred Vietnamese children of Chinese origin attended Saturday supplementary school classes at St Paul’s Way School in the eighties and nineties, most from Limehouse and the Isle of Dogs. Many had been housed across Britain but chose to leave the isolation of village homes, offered in a Home Office policy of dispersement, preferring the security of living in the metropolis – sometimes with thirteen family members in two rooms – thereby linking with community networks leading to jobs, further training and more fulfilling lives.”

Members of the Vietnamese Friendship Society.

Lathe, Whitechapel Bell Foundry – “Photographed in the eighties when the Bell Foundry was more a local point of interest, before it grew internationally famous.”

Brick Lane at Night – ” At a time when women were rarely seen on Brick Lane, I was once asked where my ‘friend’ was. I said the person I usually shopped with must be out and about – to which the questioner kindly patted my hand and whispered ‘they always come back…’ Some time passed before it dawned on me that many of the white women accompanying Asian men on the street were ‘working women’….”

Market Cafe Farewell – “Market traders, artists and local characters, ranging from Patrick who directed traffic from the Blackwall Tunnel and Tower Bridge to Commercial St- regardless of whether it flowed without his assistance – all squeezed into this one-room-cafe which opened in the early hours of each morning. Then it vanished one day with only a farewell note left to confirm where it had been.”

Photographs copyright © Daniele Lamarche

At Paul Pindar’s House

Tickets are available for my Spitalfields tour throughout October & November

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

House of Sir Paul Pindar by J.W. Amber

If William Shakespeare passed along Bishopsgate around 1600, he might have observed the construction of one of the finest of the mansions that formerly lined this ancient thoroughfare, Sir Paul Pindar’s house situated on the west side of the highway beyond the City wall next to the Priory of St Mary Bethlehem.

Paul Pindar was a City merchant who became British Consul to Aleppo and subsequently James I’s Ambassador to Constantinople. Although he returned home from his postings regularly, he did not take permanent residence in his house until 1623 when he was fifty-eight and between 1617-18 it served as the London abode of Pietro Contarini, Venetian Ambassador to the Court of St James.

Who can say what precious gifts from Sultan Mehmet III comprised the inventory of Ottoman treasures that once filled this fine house in Bishopsgate? Pindar’s wealth and loyalty to the monarch was such that he made vast loans to James and Charles I who both dined at his house, as well as contributing ten thousand pounds to the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral. Yet Charles’ overthrow in 1649 meant that Pindar was never repaid and he died with huge debts at the age of eighty-five in 1650. What times he had seen, in a life that stretched from the glory days of Elizabeth I to the decapitation of Charles I.

Remarkably, Paul Pindar’s house survived the Great Fire along with the rest of Bishopsgate which preserved its late-medieval character, lined with shambles and grand mansions, until it was redeveloped in the nineteenth century. His presence was memorialised when the building became a tavern by the name of The Paul Pindar in the eighteenth century.

Reading the correspondence of CR Ashbee from the eighteen-eighties in the archives of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in Spital Sq, I was astonished to discover that, after Ashbee’s successfully campaign to save the Trinity Green Almshouses in Whitechapel, he pursued an ultimately fruitless attempt to rescue Paul Pindar’s house from the developers who were expanding Liverpool St Station.

In his poignant letters, arguments which remain familiar in our own time are advanced in the face of the unremitting commercial ambition of the railway magnates. CR Ashbee reminded them of the virtue in retaining an important and attractive building which carried the history of the place, even proposing that – if they could not keep it in its entirety – preserving the facade integrated into their new railway station would prove a popular feature. His words were disregarded but, since Paul Pindar’s house stood where the Bishopsgate entrance to Liverpool St Station is now, I cannot pass through without imagining what might have been and confronting the melancholy recognition that the former glories of Paul Pindar’s house are forever lost in time, as a place we can never visit.

The elaborately carved frontage, which concealed a residence much deeper than it was wide, was lopped off when the building was demolished in 1890 after surviving almost three hundred years in Bishopsgate. Once the oak joinery was dis-assembled, it was cleaned of any residual paint according to the curatorial practice of the time and installed at the Victoria & Albert Museum in South Kensington when it opened in 1909. You can visit this today at the museum, where the intricate dark wooden facade of Paul Pindar’s beautiful house – familiar to James I, Charles I and perhaps to Shakespeare too – sits upon the wall as the enigmatic husk of something extraordinary. It is an exquisite husk, yet a husk nonetheless.

Sir Paul Pindar (1565–1650)

Paul Pindar’s House by F.Shepherd

View of Paul Pindar’s House, 1812

Street view, 1838

The Sir Paul Pindar by Theo Moore, 1890

The Sir Paul Pindar photographed by Henry Dixon, 1890

Paul Pindar’s House as it appeared before demolition by J.Appleton, 1890

Facade of Paul Pindar’s House at the Victoria & Albert Museum

Bracket from Paul Pindar’s House at the Victoria & Albert Museum

Paul Pindar’s Summer House, Half Moon Alley, drawn by John Thomas Smith, c. 1800

Panelled room in Paul Pindar’s House

Bishopsgate entrance to Liverpool St Station

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

The Romance of Old Bishopsgate

The Canal Club Is Saved!

Tickets are available for my Spitalfields tour throughout October & November

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Toslima Rahman with her daughter Saima & son Ayaan at the Canal Club

I am delighted to report that after an heroic three-year fight by the local community, the proposal for development has been withdrawn by the new regime at the council and the beloved Canal Club and community garden in Bethnal Green is saved.

Here is the feature that Novelist Sarah Winman wrote when she first visited with Photographer Rachel Ferriman to report on the threat to the community spaces at the Wellington Estate.

The Canal Club sits at the corner of Waterloo Gardens and Sewardstone Rd in Bethnal Green. It consists of a playground, a ball park, a community centre and community garden between the vast Wellington Estate to the east, of which it is part, and the Grand Union Housing Coop to the west. At the southern border is Belmont Wharf, a small boating community established by Sally and Dominique who were granted permission by the council nine years ago to have moorings along this stretch of Regent’s Canal and to create a sustainable garden for boat dwellers and land dwellers alike.

The garden is incredibly beautiful, a biodiverse haven. The sound of children playing carries across the water from Victoria Park and faded bunting flutters in the breeze. Flowers of every colour bloom and bees are plenty and go about with purpose. Butterflies delight around the nettles and even bats have found a home here. This garden has been created with care and thought and, more importantly, time. The air is sweet and clean, far removed from the fug of Cambridge Heath Rd and Hackney Rd that pollute nearby.

I met residents Sally, Dominique, Alex, Ricardo, Helga, Erdoo, Mr & Mrs Ali, and Toslima to learn that this beloved site had been selected by Tower Hamlets Council for a housing infill scheme. These schemes are becoming common practise by councils, who target sites – usually recreational – on existing estates and build further.

The proposal for the Wellington Estate was to demolish the Canal Club and remove the open space and community asset it provides. This was to construct a further twenty-two flats on an already densely populated estate which was built in the thirties as an answer to slum clearance – basically, it was taking space from those who have little to start with.

It was a complex situation that was the outcome of thirty years of right-to-buy, money held by central government and the chronic need for housing. However, what was inexcusable to the residents of the estate and the boating community and supportive locals, was the opaque nature of the dealings – the council’s lack of transparency and openness to discussion. Two years earlier, they thought they were simply looking at the refurbishment of their community centre, until they later found out that the decision to demolish the Canal Club site was already under way.

Alex explained that the Canal Club land was given by the GLC to the people of the Wellington Estate in the late seventies and early eighties to offset the overcrowding and the lack of balconies and gardens. It was their land and she believed the council had a responsibility to share their ideas with the residents. The irony was not lost on her too, that Tower Hamlets said they were an Climate Emergency Council and yet were taking away the only green public space on the estate.

Everyone talked about the eighties and nineties when the community centre was thriving. It was hired out for weddings and birthdays then. There was a youth club, opportunities to learn a second language and for recent immigrants to learn English, space for pensioners to get together, and for the residents association to meet and share ideas. Dwight told us he was a member of the youth club and it was the only chance for kids to have day trips out of London. He remembered camping in Tunbridge Wells. The chance to ride horses and canoe – see a different life, be a different person.

There was nothing for kids after that, someone said. So much had already gone. And if you take away the ball park, then what? Looting across the generations, another said. Building slums of the future, said another. Erdoo, who has lived on the state all her life, told me that her dad Joseph looked after the Community Centre for years before the council took away his key and barred the local residents from using it anymore. Then the Community Centre was offered up to private use for private rents. The popular Scallywags nursery is the present tenant, but ill-feeling from that time remains.

This engaging group of people cared so much about their environment and improving the lives of others. Yet what was apparent was how the agency of council tenants was being eroded in the widening chasm of inequality.

The right to space and light and clean air can never only be for the rich.

I stood on the old wharf where the custodians, Sally and Dominique, repaired it with two-hundred-year-old bricks. Wildflowers grew there and nature had reclaimed an area once used for the dumping of waste. Kick the soil and a filament of plastic was revealed, hidden by knapweed or evening primrose, or large swathes of hemp-agrimony. Over the years, composting had built up the fertility of the soil, attracting a diversity of insects and bird population. Dominique explained that the principle of permaculture is to work in sympathy with nature and harness its natural energy. A wild colony of bees appeared every year for a few weeks when the cherry tree blossoms and then disappeared again to their unknown world. Dominique kept a daily diary of the changes and visitations. The secret life that we do not see, either because we move too fast or because the insects are too small.

When the license for this garden expired, Dominique and Sally feared the council will not renew it if the demolition went ahead. I found it unbelievable that such a necessary and beautiful urban green space could be sacrificed especially in a time of declining mental health. The benefits that access to nature provides are irrefutable. This community garden is more than a garden, it is a destination for the carers and patients who come down from the Mission Practise or readers looking for solitude. It is a resource for artists seeking inspiration and children who want to know how the natural world works – or simply those who need to be reminded that they are more than their circumstance.

As I left this corner of East London, I was reminded of a speech delivered by Robert Kennedy back in the sixties about how the value of a country is measured – “It does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry… It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion… it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

The Wellington Estate

Save Our Community Spaces – Refurbish Not Demolish

In the Community Garden

Dominique Cornault at the Canal Club

Sally Hone at the Canal Club

Mr & Mrs Ali outside the Canal Club

Helga Lang at the Canal Club

Dwight James at Belmont Wharf

Erdoo Yongo outside her mum’s house on Wellington Estate

Barbara, resident of the Estate, and Bonny her dog

Photographs copyright © Rachel Ferriman

You may also like to take a look at

Frank Derrett’s West End

Tickets are available for my Spitalfields tour throughout October & November

Click here to book for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS

Cranbourne St

Fancy a stroll around the West End with Frank Derrett in the seventies?

This invitation is possible thanks to the foresight of Paul Loften who rescued these photographs from destruction in the last century. Recently, Paul contacted me to ask if I was interested and I suggested he donate them to the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute, which is how I am able to show them today.

‘They were given to me over twenty-five years ago when I called at an apartment block in Camden,’ Paul explained. ‘A woman opened the door and, when said I was from Camden Libraries, she told me a solicitor was dealing with effects of a resident who had died and was about to throw these boxes of slides into a skip, and did I want them? I kept them in my loft, occasionally enjoying a look, but actually I had forgotten about them until we had a clear out upstairs.’

Charing Cross Rd

Bear St

Coventry St

Regent St

Earlham St

Long Acre

Dover St

Carnaby St

Carnaby St

Charing Cross Rd

Cranbourne St

Dover St

Perkins Rents

Great Windmill St

Brook St

Conduit St

Frith St

Drury Lane

Dean St

Garrick St

Great Windmill St

Archer St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at