Masterplan For The Truman Brewery

Click here to book for my tour of Spitalfields this Saturday and beyond

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

For over three years, the battle for Brick Lane has been raging. The conflict has focussed upon the future of the Truman Brewery which is central to the identity of Spitalfields.

The owners want to construct a shopping mall of mostly chain stores with offices on top as – it is believed – a precursor to the redevelopment of the entire site as a corporate-style plaza in the manner of Broadgate and Spitalfields Market.

Rejecting this notion, local residents and businesses seek mixed use for the site that reflects the needs of the community for social housing and affordable workspaces. This summer the conflict approaches resolution and I have strong hopes for a positive outcome.

In response to the strength of public opinion in the borough, Tower Hamlets Council have already launched a consultation to create a planning brief for the area that can be legally enforced. Meanwhile, in June, the Save Brick Lane campaign’s legal action at the High Court to quash the shopping mall planning permission – granted by the previous regime at the council – reaches a final verdict which I believe will be in our favour.

Stopping the shopping mall is crucial to enable the community-led masterplan for the Truman Brewery to proceed to fulfilment.

SAVE BRICK LANE

Last year, Save Brick Lane challenged Tower Hamlets Council’s approval of the Truman Brewery shopping mall application in the High Court. Although the Judicial Review was initially unsuccessful, they have now been granted permission to appeal and have a real chance to win.

They are challenging Tower Hamlets Council’s act of removing an elected councillor’s statutory right to vote at the meeting deciding the Truman Brewery planning application simply because they were not present at an earlier meeting that had considered the application.

A fundamental component of our democracy – the right of elected representatives to make decisions – is at stake here. In granting permission for appeal, the judge commented:

“…the issue raised by the proposed appeal is a novel one which is arguable with a real as opposed to fanciful prospect of success. It also seems to me to have some real general importance.”

The hearing will be held in front of three judges at the Court of Appeal on 20th or 21st June. In order to proceed, Save Brick Lane needs to raise £10,000 in the next month for legal costs.

CLICK HERE TO SUPPORT SAVE BRICK LANE IN THE HIGH COURT

MASTERPLAN

Tower Hamlets Council have appointed MUF architectural practice led by architect Shahed Saleem to oversee the masterplan and supervise the community consultation. For several years, Shahed Saleem worked on Survey of London’s recent Whitechapel volume which makes him ideally placed to undertake this task, possessing a deep knowledge of both the history and the current social complexity of the place.

All readers are encouraged to participate in this project.

Click here to fill in the online consultation

Click here to join a webinar on Thursday 1st June at 6pm

Visit the stall on Saturday 3rd June from 10am to 1pm at the corner of Hanbury St and Spital St, E1 5JF.

Below are some early possibilties for the Truman Brewery site originated by Save Brick Lane

OPEN SPACE

The two large courtyards within the brewery complex to the east and west of Brick Lane could become designated public squares.

ROADS & PATHWAYS

The neighbourhood could benefit from opening up the roads and paths through the brewery site for public use.

A Open up large courtyard to Buxton St and Allen Gardens.

B Open up passageways between Brick Lane and eastern yard.

C Open up entrance between western yard and Grey Eagle St to improve access from Commercial St.

D Fully reopen the extension of Wilkes St, connecting Hanbury St and Quaker St.

USES

The brewery site offers the potential for new housing and other uses that would benefit the community.

A Housing at the corner of Buxton St and Spital St overlooking Allen Gardens.

B A terrace of live/work dwellings on Woodseer St each with a family-sized back garden. These should match the height of the existing nineteenth century terrace on the facing side of Woodseer St.

C Rebuild the pub on the corner of Brick Lane and Woodseer St.

D There is the potential for housing and small workshops with an independent corner shop replacing the vacant lots and derelict properties in Grey Eagle St and Calvin St.

Go to WWW.BATTLEFORBRICKLANE.COM for more information about the campaign

You may also like to read about

Sebastian Harding At Paul Pindar’s House

Click here to book for my tour of Spitalfields this Saturday and beyond

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Today, writer and model maker Sebastian Harding begins an occasional series exploring the forgotten histories of lost buildings

Model by Sebastian Harding

Which singular building links James I, the twilight days of the Ottoman Empire and the Great Eastern Railway? The answer is – or was – Sir Paul Pindar’s house.

At the time of writing, a fierce debate rages over the future of Liverpool Street Station. The station is a monument to the wealth and power of the Great Eastern Railway and it is not the first time that preservationists have fought to conserve this corner of the ancient ward of Bishopsgate, upon which it stands.

In the eighteen-nineties, remarkably similar arguments were undertaken over the fate of the magnificent sixteenth century townhouse that once stood on this site. At that time, the façade of Paul Pindar’s home had been witness to the traffic of Norton Folgate flowing along this great arterial road for almost three centuries. This was not just any old merchants’ house, Sir Paul Pindar’s remarkably fine house was in a league of its own and as fascinating as the man himself.

First let us pause to consider the building. The slender facade was not vast but what it lacked in size it made up in style. Each element of the façade was designed to convey the wealth and social stature of its owner.

Let us begin with the windows. Created at a time when glass was still a luxury, the double-height casements spanning the full width of the façade must have stopped rich and poor alike in their tracks. These tall windows were set within a complex piece of joinery, featuring a rounded central bay and with each jettied storey projecting a little further out. It meant that the building, and specifically the expanse of glass in the windows, would have been visible from a hundred feet in either direction. What a sight it must have been to see all that glass shimmering in the sunlight. Not dissimilar to the effect of witnessing the Gherkin at sunset in the City today.

The ostentation did not stop there. Decoration extended from the carved wooden window panels complete with a unicorn, James I’s own symbol, to the sculpted posts of mythic beasts supporting the upper storeys.

So who was Paul Pindar and how did he amass the fortune to build this highly embellished, well-located home? Perhaps this is where my own affinity for this enigmatic figure begins. Like me, Pindar was a Midlands boy who left his birthplace in his teens to seek opportunity in the capital.

Hailing from the small Northamptonshire village of Wellingborough, he was thrust into the melting pot of Elizabethan London. Pindar arrived in the mid-fifteen-eighties and he soon found employment as apprentice to John Powish, a merchant with Italian connections. Over the proceeding fifteen years, Pindar succeeded in gathering wealth and connections through trade in Italy and southern Europe.

By the age of thirty-four he was prosperous enough to build the house that would bear his name but his success did not stop there. Twelve years later, Pindar’s skill as a merchant and his political wit rewarded him with a position as James I’s ambassador to the Sultan of Turkey in Constantinople.

Since the late fifteen hundreds, Britain and the Ottoman Empire had been equally concerned about the strength of Spain. By joining forces, they hoped to be able to defend their interests against Spanish aggression.

Here we spy another tantalising glimpse of the personality of our Midlands-born merchant ambassador. As ambassador, Pindar became a great favourite of Mehmed III’s mother, the Safiye Sultan. It was even recorded that “the sultana did take a great liking to Mr. Pindar, and afterward, she sent for him to have his private company” By this point Safiye was sixty-one, so we may speculate the connection was platonic. Yet, whatever the basis of their kinship, this Northampton lad had certainly come a long way.

After his time in the east, Pindar returned home and appears to have passed the remainder of his days in peace and comfort, living to his eighty-fifth year. A significant lifespan when the average life expectancy was just thirty-five years.

After his death, the house became synonymous with his name, clinging on to its faded grandeur even as the city expanded eastwards – Pindar had built the house on fields – and the building changed use. By the eighteenth century, it was known as a popular tavern with a prime location at the foot of the Old North Road that made it the perfect watering hole for travellers from Essex and Cambridge.

A century later, the pub was the subject of a dystopian scene by Gustav Doré, who depicted the bustling thronged masses of the East End swarming around the building. In Doré’s engraving, a sign gives the name of the establishment as “SIR PAUL PINDAR STOUT HOUSE’. A woman sells food from a basket in the doorway. Weary figures push wheelbarrows piled with vegetables whilst lithe and ill-kempt men huddle together. A more miserable vision could not be depicted and anyone might think twice about visiting the scene. Given this context, perhaps it was no surprise that the Great Eastern Railway sought to sweep it away with their new railway station.

The house withstood the first phase of the Liverpool Street Station development in the eighteen-seventies but, with the expansion of the platforms, it was only a matter of time before it was demolished. Thankfully the house survived long enough to be documented in etchings, paintings and photographs.

Today you will look in vain for any trace of Paul Pindar’s house in Bishopsgate, though if you travel to Kensington one fragment of the structure survives. The Great Eastern Railway donated the wooden façade of the building to the Victoria & Albert Museum where it is displayed to this day. It stands as a tantalising reminder of what once was and a solemn reminder of the importance of preserving our built heritage.

Sir Paul Pindar (1565–1650)

House of Sir Paul Pindar by J.W. Amber

Paul Pindar’s House by F.Shepherd

View of Paul Pindar’s House, 1812

Street view, 1838

Paul Pindar’s House by Gustave Doré, 1872

The Sir Paul Pindar by Theo Moore, 1890

The Sir Paul Pindar photographed by Henry Dixon, 1890

Paul Pindar’s House as it appeared before demolition by J.Appleton, 1890

Facade of Paul Pindar’s House at the Victoria & Albert Museum

Bracket from Paul Pindar’s House at the Victoria & Albert Museum

Paul Pindar’s Summer House, Half Moon Alley, drawn by John Thomas Smith, c. 1800

Panelled room in Paul Pindar’s House

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Anthony Eyton, Centenarian Artist

Click here to book for my tour of Spitalfields this Saturday and beyond

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Today we are celebrating artist Anthony Eyton who reached his centenary last week on 17th May

I took the 133 bus from Liverpool St Station, travelling down south of the river to visit painter Anthony Eyton at the elegant terrace in the Brixton Rd where has lived since 1960 – apart from a creative sojourn in Spitalfields, where he kept a studio from 1968 until 1982.

It was the 133 bus that stops outside his house which brought Anthony to Spitalfields, and at first he took it every day to get to his studio. But then later, he forsook home comforts to live a bohemian existence in his garret in Hanbury St and the result was an inspired collection of paintings which exist today as testament to the particular vision Anthony found in Spitalfields.

A tall man with of mane of wiry white hair and gentle curious eyes, possessing a benign manner and natural lightness of tone, Anthony still carries a buoyant energy and enthusiasm for painting. I found him working to finish a new picture for submission to the Royal Academy before five o’clock that afternoon. Yet once I arrived off the 133, he took little persuasion to lay aside his preoccupation of the moment and talk to me about that significant destination at the other end of the bus route.

“That biggest strangest world, that whirlpool at Spitalfields, and all the several colours of the sweatshops, and the other colours of the degradation and of the beautiful antique houses derelict – I think the quality of colour was what struck me most,” replied Anthony almost in a whisper, when I asked him what drew him to Spitalfields, before he launched into a spontaneous flowing monologue evoking the imaginative universe that he found so magnetically appealing.

“From Brick Lane to Wilkes St and in between was special because it’s a kind of sanctuary,” he continued, “and looking down Wilkes St, Piero della Francesca would have liked it because it has a kind of perfection. The people going about their business are perfectly in size to the buildings. You see people carrying ladders and City girls and Jack the Ripper tours, and actors in costume outside that house in Princelet St where they make those period films, and they are all in proportion. And the market was still in use then which gave it a rough quality before the City came spilling over and building its new buildings. Always a Mecca on a Sunday. I used to think they were all coming for a religious ceremony, but it’s pure commerce, and it’s still there and it’s so large. It’s very strange to me that people give up Sunday to do that… – It’s a very vibrant area , and when Christ Church opens up for singing, the theatre of it is wonderful.”

Many years before he took a studio in Spitalfields, Anthony came to the Whitechapel Gallery to visit the memorial exhibition for Mark Gertler in 1949, another artist who also once had a studio in an old house in one of the streets leading off the market place. “Synagogues, warehouses, and Hawksmoor’s huge Christ Church, locked but standing out mightily in Commercial St, tramps eating by the gravestones in the damp church yard. “Touch” was the word that recurred,” wrote Anthony in his diary at that time, revealing the early fascination that was eventually to lead him back, to rent a loft in an eighteenth century house in Wilkes St and then subsequently to a weavers’ attic round the corner in Hanbury St where the paintings you see below were painted.

Each of these modest spaces were built as workplaces with lines of casements on either side to permit maximum light, required for weaving. Affording vertiginous views down into the quiet haven of yards between the streets where daylight bounces and reflects among high walls, these unique circumstances create the unmistakable quality of light that both infuses and characterises Anthony Eyton’s pictures which he painted in his years there. But while the light articulates the visual vocabulary of these paintings, in their subtle tones drawn from the buildings, they record elusive moments of change within a mutable space, whether the instant when a model warms herself at the fire or workmen swarm onto the roof, or simply the pregnant moment incarnated by so many open windows beneath an English sky.

Anthony’s youngest daughter, Sarah, remembers coming to visit her father as a child. “It was a bit like camping, visiting daddy’s studio,” she recalled fondly, “There were no amenities and you had to go all the way downstairs, past the door of the man below who always left a rotten fish outside, to visit the privy in the yard that was full of spiders which were so large they had faces. But it was exciting, an adventure, and I used to love drawing and doing sketches on scraps of paper that I found in his studio.”

For a few years in the midst of his long career, Spitalfields gave Anthony Eyton a refuge where he could find peace and a place packed with visual stimuli – and then a quarter of a century after he left, Anthony returned. Frances Milat who was born and lived in the house in Hanbury St came back from Australia to stage a reunion of all the tenants from long ago. It was the catalyst for a set of circumstances which prompted Anthony to revisit and do new drawings in these narrow streets which, over all this time, have become inextricable with his identity as an artist.

Christine, 1976/8 – “She was very keen that the cigarette smoke and grotty ashtray should be in the picture to bring me down to earth.”

Liverpool St Station, mid-seventies

Studio interior, 1977

Back of Princelet St, 1980

Girl by the fire, 1978

Workers on the roof, 1980

Open window, Spitalfields, 1976-81 (Courtesy of Tate Gallery)

Open window, Spitalfields, 1976

Anthony Eyton working in his Hanbury St studio, a still from a television documentary of 1980

Pictures copyright © Anthony Eyton

You may also like to read about

At The Bulmer Brick & Tile Company

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

The kiln

Brick Lane takes its name from the brick works that once filled Spitalfields and I always wondered how it was in those former times. So you can imagine my delight to visit Bulmer Brick & Tile Company in Suffolk, where bricks have been made since 1450, and be granted a glimpse of that lost world.

My guide on this journey through time was Peter Minter who has been making bricks in the traditional way for over seventy years. He began by taking me to the hole in the ground where they dig out the mud and pointing out the strata differentiated in tones of brown and grey. ‘You are looking at the Thames Estuary thirty-six million years,’ he declared with a mild grin of philosophical recognition.

At the lowest level is London clay, deposited in primordial times when the Thames flowed through Suffolk, used to make familiar stock bricks of which most of the capital was constructed in previous centuries. ‘Each of the strata here offer different qualities of clay for different purposes,’ Peter explained as he pointed out dark lines formed of volcanic ash that fell upon the estuary a mere twenty-five million years ago. ‘We have another fifty years of clay at this site,’ he admitted to me in the relaxed tone that is particular to a ninety-year-old brick maker.

“My father, Lawrence Minter, took over this brick works in 1936 when he was thirty-five. It had been here for hundreds of years, with the earliest evidence dating from 1450, and it was a typical local brick works. His uncle, FG Minter, was a builder in London and my father was brought up by him as a surveyor.

Before my father could get established, the war came along and shut the place down. There were thirty-five or thirty-six people working here but a lot got called up and we went down to about six or seven men. We made land drain pipes for the Ministry of Supplies and that was what kept us going. Those men were old or infirm but they kept the skills alive.

I was taught by those skilled men who had been born in the nineteenth century and brought up as brick makers. Without realising, I learnt all the old secrets of brick making but it was only when I knew that this was the direction of my life that I decided I had to save it, and started using the old techniques that had been forgotten rather than the new. This is what makes us unique. I have spent my whole life working here and I probably know more about making bricks than anyone alive. The business has changed and yet it has not changed, because the essence is the same.

When my father reopened after the war, everything was already beginning to change. There was so little trade in brick making that he got into the restoration business. When conservation started to develop, I was the only person in the country who knew how to manufacture bricks in the traditional way. Other people have theories but I am the only one who knows how to do it. There is no-one with our philosophy and the way we go about it.

We start backwards. We look at an old house and its history. We do not think simply of the profit we can make from selling you a brick. We work out why the bricks were made the way they were and how they were made, what techniques were used at that time. When I look at a building, I can tell you everything about its history this way.

In London, they were manufacturing what they called the ‘London Stock,’ the cheapest brick they could produce and they used all sorts of waste material in it as well as clay. They did not think about it lasting but it turned out to be one of the finest bricks of all time. That is what they would have been making in Brick Lane in the seventeenth century.

The clay is the secret because whatever have got beneath your feet is what you have to use, its characteristics dictate what you can make. We are digging out the clay for the next summer, we always do it at the end of September and try to catch the end of the good weather, which we have just done. We want it dry and crumbly, we do not want it compressed into mud. It needs to weather, so the salts and minerals in it liberate into the atmosphere, and you avoid getting salt crystallising upon the finished bricks.

When father was running the brick works, he simply dug the clay out but gradually we have become more precise so now we select layers of clay for different jobs. In his day, you bought a brick from Bulmer – father only did ‘Tudor’ – but now we make bricks specially for each particular job. More and more of our work involves some kind of experimentation. We no longer make generic bricks, everything is specialised now. We make over one hundred and fifty different kinds of bricks in a year. We look at our clay for its degree of plasticity, the grey clay is more plastic whereas yellow clay is more sandy, so we blend the clay as necessary for each order of bricks.

We are currently making around 30,000 bricks for Kensington Palace and another 30,000 for the Tower of London. We have been making bricks for Hampton Court since 1957. For thirty years, we supplied the clay for the moulds at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and the ‘bell bricks’ which were the radius bricks upon which they placed the mould.

Our bricks are laid out to air dry before firing in what are called ‘hack rows’ on the ‘hack ground’ or ‘hack stead.’ These are Saxon words. Once the bricks are dry enough, we set them up in ordered lines which is called ‘skinking.’ We have covers to ensure even drying, by keeping off the sun and the rain. If they get wet, they just turn back to mud.

Once a fortnight, we fire the kiln for three days. Someone has to stay to stoke the fires continuously. I rebuilt one of the kilns myself a few years ago. I have been responsible for the construction of four of these domed-roof kilns. I could not find an expert to tell me how to do it, so I worked out how to do it myself. I did not use a wooden frame for the dome, I built it in concentric circles of bricks so it was self supporting. As a child in 1936, I remembered the original kiln being built and the man looking down through the hole in the roof without any former supporting the dome, so I knew it was possible. He was obviously very proud of what he had built, he took me outside and drew a diagram in the dust with a stick to show me how he had built it. He said, ‘When you want to rebuild it, this is what you do.’

It is a down-draught brick kiln with seven fires around the outside to heat it, the heat is drawn up to the domed roof and down through the bricks to escape through the floor. It reaches about 1200 degrees centigrade and some of the brick lining has turned to glass.

Each aspect of brick making requires different skills and we are continually honing those skills and training new people. It takes five years to train a brick maker. I have two sons in the business here and one of them has two sons, so in time they will be taking over.”

Peter Minter, seventy years a brick maker

Thames mud used for London stock bricks

Making a shaped brick in a wooden mould

Jack has been a brick maker for two years

“He’s coming into quite a good brick maker’

Marking a batch of shaped bricks

Setting the bricks out to dry on the hack ground

Stacking bricks in this way is called ‘skinking’

The hack ground

The rough cut pieces of timber around the kiln that allow smoke to escape are known as ‘skantlings.’

Seven fires heat the kiln

Store for brick moulds

The Bulmer Brick & Tile Company, The Brickfields, Bulmer, Suffolk CO10 7EF

The Secret Gardens Of Spitalfields

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Gardens in Spitalfields are open for visitors this year on Saturday 10th June from 10am – 4pm. Find details at the website of the National Gardens Scheme. If you are clever you can even fit in my tour of Spitalfields on the same day.

These hidden enclaves of green are entirely concealed from the street by the houses in front and the tall walls that enclose them. If you did not know of the existence of these gardens, you might think Spitalfields was an entirely urban place with barely a leaf in sight, but in fact every terrace conceals a string of verdant little gardens and yards filled with plants and trees that defy the dusty streets beyond.

You may also like to read about

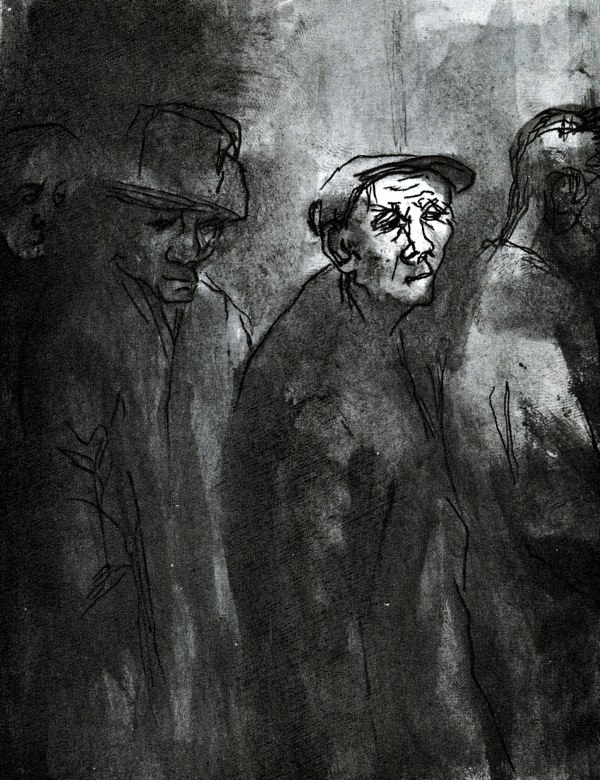

Eva Frankfurther’s Drawings

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

There is an unmistakeable melancholic beauty which characterises Eva Frankfurther‘s East End drawings made during her brief working career in the nineteen-fifties. Born into a cultured Jewish family in Berlin in 1930, she escaped to London with her parents in 1939 and studied at St Martin’s School of Art between 1946 and 1952, where she was a contemporary of Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach.

Yet Eva turned her back on the art school scene and moved to Whitechapel, taking menial jobs at Lyons Corner House and then at a sugar refinery, immersing herself in the community she found there. Taking inspiration from Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Picasso, Eva set out to portray the lives of working people with compassion and dignity.

In 1958, afflicted with depression, Eva took her own life aged just twenty-eight, but despite the brevity of her career she revealed a significant talent and a perceptive eye for the soulful quality of her fellow East Enders.

“West Indian, Irish, Cypriot and Pakistani immigrants, English whom the Welfare State had passed by, these were the people amongst whom I lived and made some of my best friends. My colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end – the understanding of and commenting on people.” – Eva Frankfurther

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also wish to take a look at

The Fate Of The White Hart

Click here to book for my next City of London walk on 4th June

Click here to book for my Spitalfields walk tomorrow and beyond

If you are concerned about the proposed redevelopment of Liverpool St Station – which includes plonking a tower block on top of the grade II listed Great Eastern Hotel – take heed from the pitiful fate of the historic White Hart tavern just across the road. Click here to sign the petition to Save Liverpool St Station

The White Hart (1246-2015)

Charles Goss, one of the first archivists at the Bishopsgate Institute, was in thrall to the romance of old Bishopsgate and in 1930 he wrote a lyrical history of The White Hart, which he believed to be its most ancient tavern – originating as early as 1246. “Its history as an inn can be of little less antiquity than that of the Tabard, the lodging house of the feast-loving Chaucer and the Canterbury pilgrims, or the Boar’s Head in Eastcheap, the rendezvous of Prince Henry and his lewd companions.” – Charles Goss

In Goss’ time, Bishopsgate still contained medieval shambles that were spared by the Fire of London and he recalled the era before the coming of the railway, when the street was lined with old coaching inns, serving as points of departure and arrival for travellers to and from the metropolis. “During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, The White Hart tavern was at the height of its prosperity.” he wrote fondly, “It was a general meeting place of literary men of the neighbourhood and the rendezvous of politicians and traders, and even noblemen visited it.”

The White Hart’s history is interwoven with the founding of the Hospital of St Mary Bethlehem in 1246 by Simon Fitz Mary, whose house once stood upon the site of the tavern. He endowed his land in Bishopsgate, extending beneath the current Liverpool St Station, to the monastery and Goss believed the Brothers stayed in Fitz Mary’s mansion once they first arrived from Palestine, until the hospital was constructed in 1257 with the gatehouse situated where Liverpool St meets Bishopsgate today. This dwelling may have subsequently became a boarding house for pilgrims outside the City gate and when the first licences to sell sweet wines were issued to three taverns in Bishopsgate in August 1365, this is likely to have been the origin of the White Hart’s status as a tavern.

Yet, ten years later in 1375, Edward III took possession of the monastery as an ‘alien priory’ and turned it over to become a hospital for the insane. The gateway was replaced in the reign of Richard II and the date ‘1480’ that adorned the front of the inn until the nineteenth century suggests it was rebuilt with a galleried yard at the same time and renamed The White Hart, acquiring Richard’s badge as its own symbol. The galleried yard offered the opportunity for theatrical performances, while increased traffic in Bishopsgate and the reputation of Shoreditch as a place of entertainments drew the audience.

“Vast numbers of stage coaches, wagons, chaises and carriages passed through Bishopsgate St at this time,” wrote Goss excitedly, “Travellers and carriers arriving near the City after the gates had been closed or those who for other reasons desired to remain outside the City wall until the morning, would naturally put up at one of the galleried inns, or taverns near the City gate and The White Hart was esteemed to be one of the most important taverns at that time. Here they would find small private rooms, where the visitors not only took their meals but transacted all manner of business and, if the food dispensed was good enough, the wine strong, the feather beds deep and heavily curtained, the bedrooms were certainly cold and draughty, for the doors opened onto unprotected galleries – but apparently they were comfortable enough for travellers in former days.”

The occasion of Charles Goss’ history of The White Hart was the centenary of its rebuilding upon its original foundations in 1829, yet although the medieval structure above ground was replaced, Goss was keen to emphasise that, “When the tavern was taken down it was found to be built upon cellars constructed in earlier centuries. Those were not destroyed, but were again used in the construction of the present house.” This rebuilding coincided with Bedlam Gate being removed and the road widened and renamed Liverpool St, after the Hospital of St Mary Bethlehem had transferred to Lambeth in 1815. At this time, the date ‘1246 ‘- referring to the founding of the monastery – was placed upon the pediment on The White Hart where it may be seen to this day.

“This tavern which claims to be endowed with the oldest licence in London, is still popular, for its various compartments appear always to be well patronised during the legal hours they are open for refreshment and there can be none of London’s present-day inns which can trace its history as far back as The White Hart, Bishopsgate,” concluded Goss in satisfaction in 1930.

In 2011, permission was granted by the City of London to demolish all but the facade of The White Hart and in 2015 the pub shut for the last time to permit the construction of a nine storey cylindrical office block of questionable design, developed by Sir Alan Sugar’s company Amsprop. Thus passed The White Hart after more than seven centuries in Bishopsgate, and I am glad Charles Goss was not here to see it.

The White Hart by John Thomas Smith c. 1800

The White Hart from a drawing by George Shepherd, 1810

White Hart Court, where the coaches once drove through to the galleried yard of the White Hart

Design by Inigo Jones for buildings constructed in White Hart Court in 1610

Seventeenth century tavern token, “At The White Hart”

Reverse of the Tavern Token ” At Bedlam Gate 1637″

The White Hart as it appeared in 1787

The White Hart, prior to the rebuilding of 1829

“When the tavern was taken down it was found to be built upon cellars constructed in earlier centuries. Those were not destroyed, but were again used in the construction of the present house.” Charles Goss describing the rebuilding of 1829. These ancient vaults were destroyed in the current redevelopment.

The White Hart in 2015

The White Hart today

Seen from the churchyard of St Botolph’s Bishopsgate by James Gold, 1728

Seen from the south west

Seen from Liverpool St

The meeting of the old and new in Liverpool St

Archive images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read about

Griff Rhys Jones on Liverpool St Station

Towering Folly at Liverpool St Station

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY OF THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM