Leo Epstein, Epra Fabrics

Let me take you underground and show you this lost fragment of the Roman Wall marooned in a subterranean car park. There are only two left this summer – Sunday 2nd July and Sunday 6th August at 2pm

Enjoy a storytelling ramble across the Square Mile, from the steps of St Paul’s through the narrow alleys and lanes to the foot of old London Bridge, in search of the wonders and the wickedness of the City of London.

Click here to book tickets for my Spitalfields and my City of London tours

Leo Epstein

When the genial Leo Epstein, proprietor of Epra Fabrics said to me, “I am the last Jewish trader on Brick Lane,” he said it with such a modest balanced tone that I knew he was just stating a fact and not venturing a comment.

“If you’re not a tolerant sort of person you wouldn’t be in Brick Lane,” he added before scooting across the road to ask his neighbour at the Islamic shop to turn down the Friday prayer just a little. “I told him he can have it as loud as he wants after one o’clock when I’ve gone home,” he explained cheerily on his return. “We all get on very well,” he confirmed.”As one of my Bengali neighbours said to me, ‘On Brick Lane, we do business not politics.'”

While his son was in Israel organising Leo’s grandson’s wedding, Leo was running the shop single-handedly, yet he managed – with the ease and grace of over half a century of experience – to maintain the following monologue whilst serving a string of customers, cutting bolts of fabric, answering the endless phone calls and arranging a taxi to collect an order of ten rolls of velvet.

“I started in 1956, when I got married. I used to work for a company of fabric wholesalers and one of our customers on Brick Lane said, “There’s a shop to let on the corner, why don’t you take it?” The rent was £6.50 a week and I used to lie awake at night thinking, “Where am I going to find it?” You could live on £10 a week then. My partner was Rajchman and initially we couldn’t decide which name should come first, combining the first two letters of our names, but then we realised that “Raep” Fabrics was not a good trade name and so we became “Epra” Fabrics.

In no time, we expanded and moved to this place where we are today. In those days, it was the thing to go into, the fabric trade – the City was a closed shop to Jewish people. My father thought that anything to do with rebuilding would be a good trade for me after the war and so I studied Structural Engineering but all the other students were rich children of developers. They drove around in new cars while I was the poor student who could barely afford my bus fare. So I said to my father, “I’m not going to do this.” And the openings were in the shmutter trade, I didn’t ever see myself working in an office. And I’ve always been happy, I like the business. I like the social part.

In just a few years, the first Indians came to the area, it’s always been a changing neighbourhood.The first to come were the Sikhs in their turbans, and each group that came brought their trades with them. The Sikhs were the first to print electronic circuits and they had contacts in the Far East, they brought the first calculators. And then came the Pakistanis, the brought the leather trade with them. And the Bengalis came and they were much poorer than the others. They came on their own, as single men, at first. The head of the family, the father would come to earn the money to send for the rest of the family. And since they didn’t have women with them, they opened up canteens to feed themselves and then it became trendy for City gents to come and eat curry here and that was the origin of the curry restaurants that fill Brick Lane today.

Slowly all the Jewish people moved away and all their businesses closed down. Twenty years ago, Brick Lane was a run down inner city area, people didn’t feel safe – and it still has that image even though it’s a perfectly safe place to be. I’ve always like it here.”

At any time over the last half a century, you could have walked up Fashion St, crossed Brick Lane and entered Epra Fabrics to be greeted by Leo, saying “Good morning! May I help you?’ with respect and civility. After all those years, it was no exaggeration when he said, “Everyone knows me as Leo.” A tall yet slight man, always formally dressed with a kippa, he hovered at the cash desk, standing sentinel with a view through the door and West along Fashion St to the towers of the City.

In his shop you found an unrivalled selection of silks and satins. “This is Brick Lane not Park Lane,” was one of Leo’s favourite sayings, indicating that nothing cost more than a couple of pounds a metre. “We only like to take care of the ladies,” was another, indicating the nature of the stock, which was strong in dress fabrics.

“I lived through the war here, so the attack wasn’t really that big a deal,” he said with a shrug, commenting on the Brick Lane nail bomb of 1999 laid by racist David Copeland, which blew out the front of his shop, “Luckily nobody was seriously hurt because on a Saturday everything is closed round here, it’s a tradition going back to when it was a Jewish area, where everything would close for the Sabbath.”

“Many of the Asian shop owners come in from time to time and say,’Oh good, you’re still here! Why don’t you come and have a meal on us?’ You can’t exist if you don’t get on with everybody else. It was, in a way, a weirdly pleasant time to see how everyone pulled together.” he concluded dryly, revealing how shared experiences brought him solidarity with his neighbours.

Leo Epstein was the last working representative of the time when Brick Lane and Wentworth St was a Jewish ghetto and the heart of the schmutter trade, but to me he also exemplified the best of the egalitarian spirit that exists in Brick Lane, defining it as the place where different peoples co-exist peacefully.

Among The Druids On Primrose Hill

Architects and engineers puzzle over what to do with a poor lonely facade in the City of London yesterday. Join my walk through the Square Mile and learn more about facadism. There are only two left this summer – Sunday 2nd July and Sunday 6th August at 2pm

Enjoy a storytelling ramble across the Square Mile, from the steps of St Paul’s through the narrow alleys and lanes to the foot of old London Bridge, in search of the wonders and the wickedness of the City of London.

Click here to book tickets for my Spitalfields and my City of London tours

In the grove of sacred hawthorn

One Midsummer years ago, my friend the photographer Colin O’Brien & I joined the celebrants of the Loose Association of Druids on Primrose Hill for the solstice festival hosted by Jay the Tailor, Druid of Wormwood Scrubs. As the most prominent geological feature in the Lower Thames Valley, it seems likely that this elevated site has been a location for rituals since before history began.

Yet this particular event owes its origin to Edward Williams, a monumental mason and poet better known by his bardic name Iolo Morganwg, who founded the Gorsedd community of Welsh bards here on Primrose Hill in June 1792. He claimed he was reviving an ancient rite, citing John Tollund who in 1716 summoned the surviving druids by trumpet to come together and form a Universal Bond.

Consequently, the Druids began their observance by gathering to honour their predecessor at Morganwg’s memorial plaque on the viewing platform at the top of the hill, where they corralled bewildered tourists and passing dog walkers into a circle to recite his Gorsedd prayer in an English translation. From here, the Druids processed to the deep shade of the nearby sacred grove of hawthorn where biscuits and soft drinks were laid upon a tablecloth with a bunch of wild flowers and some curious wooden utensils.

Following at Jay the Tailor’s shoulder as we strode across the long grass, I could not resist asking about the origin of his staff of hawthorn intertwined with ivy. “It was before I became a Druid, when I was losing my Christian faith,” he confessed to me, “I was attending a County Fair and a stick maker who had Second Sight offered to make it for me for fifteen pounds.” Before I could ask more, we arrived in the grove and it was time to get the ritual organised. Everyone was as polite and good humoured as at a Sunday school picnic.

A photocopied order of service was distributed, we formed a circle, and it was necessary to select a Modron to stand in the west, a Mabon to stand in the north, a Thurifer to stand in the east and a Celebrant to stand in the South. Once we all had practised chanting our Greek vowels while processing clockwise, Jay the Tailor rapped his staff firmly on the ground and we were off. A narrow wooden branch – known as the knife that cannot cut – was passed around and we each introduced ourselves.

In spite of the apparent exoticism of the event and the groups of passersby stopping in their tracks to gaze in disbelief, there was a certain innocent familiarity about the proceedings – which celebrated nature, the changing season and the spirit of the place. In the era of the French and the American Revolutions, Iolo Morganwr declared Freedom of Thought, Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Association. Notions that retain strong resonance to this day.

Once the ritual wound up, we had exchanged kisses of peace Druid-style and everyone ate a biscuit with a gulp of apple juice, I was able to ask Jay the Tailor more questions.“I lost my Christian faith because I studied Theology and I found it difficult to believe Jesus was anything other than a human being, even though I do feel he was a very important guide and I had a personal experience of Jesus when I met Him on the steps of Oxford Town Hall,” he admitted, leaving me searching for a response.

“When I was fourteen, I went up Cader Idris at Midsummer and spent all night and the next day there, and the next night I had a vision of Our Lady of Mists & Sheep,” he continued helpfully,“but that just added to my confusion.” I nodded sagely in response.“I came to Druids through geometry, through studying the heavens and recognising there is an order of things,” he explained to me, “mainly because I am a tailor and a pattern cutter, so I understand sacred geometry.” By now, the other Druids were packing up, disposing of the litter from the picnic in the park bins and heading eagerly towards the pub. It had been a intriguing afternoon upon Primrose Hill.

“Do not tell the priest of our plight for he would call it a sin, but we have been out in the woods all night, a-conjuring the Summer in!” – Rudyard Kipling

Sun worshippers on Primrose Hill

Memorial to Iolo Morganwg who initiated the ritual on Primrose Hill in 1792

Peter Barker, Thurifer – “I felt I was a pagan for many years. I always liked gods and goddesses, and the annual festivals are part of my life and you meet a lot of good people.”

Maureen – “I’m a Druid, a member of O.B.O.D. (the Order of Bards, Ovates & Druids), and I’ve done all three grades”

Sarah Louise Smith – “I’m training to be a druid with O.B.O.D. at present”

Simeon Posner, Astrologer – “It helps my soul to mature, seeing the life cycle and participating in it”

John Leopold – “I have pagan inclinations”

Jay the Tailor, Druid of Wormwood Scrubs

Iolo Morgamwg (Edward Williams) Poet & Monumental Mason, 1747-1826

Photographs copyright © Estate of Colin O’Brien

You may also like to read about

Peta’s Bridle’s Watery London

Let me show you this 18th century graffiti on St Paul’s Cathedral…join my walk through the City of London. There are only two left this summer – Sunday 2nd July and Sunday 6th August at 2pm

Enjoy a storytelling ramble across the Square Mile, from the steps of St Paul’s through the narrow alleys and lanes to the foot of old London Bridge, in search of the wonders and the wickedness of the City of London.

Click here to book tickets for my Spitalfields and my City of London tours

Today it is my pleasure to publish Peta Bridle‘s new drawings and captions, all on a watery theme

Pump, St. Leonard’s Churchyard, Shoreditch

This churchyard is a quiet place to draw despite the procession of traffic and buses beyond the railings. A brolly propped over my legs kept my drawing dry in the drizzle. I returned a few days later to make a second pencil sketch and the ground was carpeted with daisies and celandines, and geraniums had been planted around the base of the pump. I met the gardener who told me stories of the area and its people, and kindly made me a cup of tea. The cast iron pump has lost its handle and the nozzle is only a stump now but it once provided clean drinking water to local people. A spring rises beneath the pump that is the source of the ‘suer’ from which Shoreditch got its name and which became the river Walbrook when it reached the City of London. A well has been on this spot since Roman times.

Cody Dock, River Lea

A colourful bridge spans the river here. Cody Dock is now a community space with a cafe and gardens. The bridge was built in 1871 to unload coal from barges but, before that, the area was marshland.

Cannon St Station seen from Bankside

Last year I visited a rooftop garden at Bankside overlooking Cannon St Station across the river.

Coal Drops Yard, King’s Cross

Thirty years ago when I first moved to London I rented a flat near King’s Cross Station. At the time I found the rundown streets surrounding the old station forbidding and would not even venture down them, though now I wish I had. Coal Drops Yard was the goods yard receiving and storing coal arriving from the north by rail. In 2018, the area was transformed and old buildings repurposed into shops and restaurants to become a tourist destination. The Regent’s Canal winds around the side of the yard, separating it from the station.

Nelson Dry Dock, Rotherhithe

To reach Nelson Dry Dock involves walking in thick soft mud. Engineers Mills & Knight Ltd Ship Repairs is painted in bold red lettering around the yellow wrought iron gate. The dock closed in 1968 and now sits within a hotel complex. You only get this view from the foreshore or the water.

Battersea Power Station

I sat out on the coal jetty facing the great bulk of the power station to make my sketch until the cold and drizzle drove me inside. Located on the south bank of the Thames, the decommissioned Grade II coal-powered station is now redeveloped as a destination with flats, shops and restaurants – quite an amazing place to visit.

Padlock by W.M. & A. Quiney, Rotherhithe

William Matthew Quiney and his brother Alfred took over their father’s nail-making business on Paradise St, Rotherhithe, in 1865. They opened three warehouses and their iron and steel merchants’ business was still trading in 1910. This padlock and chain, which has the maker’s name stamped upon it, is from the wonderful collection of items found by mudlark Monika Buttling-Smith and reproduced with her kind permission.

Ragged School Museum, Mile End

A view of the school across the Regent’s Canal. It opened in 1877 to provide education for the children of Mile End and is now a museum, showing the reality of Victorian life for the poor.

Religious river finds

Three religious offerings found in the Thames including a clay pot for burning incense, a Ganesh statue and a golden amulet tied with string. Drawn with kind permission of mudlark Monika Buttling-Smith.

Star Yard Urinal, Holborn

This beautiful Victorian urinal is in Star Yard Alley off Chancery Lane. Painted pale blue, decorated in patterns and a royal coat of arms, it has survived in situ to this day. I made my sketch on a Sunday afternoon and a few passers by queried why I was drawing an old toilet. Geoffrey Fletcher – my drawing hero – sketched the urinal in the sixties and I was happy to discover it still here, even if no longer in use.

St Clement’s Watch House, Strand Lane

The Old Watch House can be found downhill from the Strand and not far from Charing Cross Station. Behind the railings is a Roman bathhouse which was once a cistern, later used as a bathing pool. Where I was sitting, I could hear a singer practising scales mixed with the sound of water gurgling down a drain.

Barge Master & Swan Marker, St James Garlickhythe

Outside St James Garlickhythe stands this beautiful bronze statue of the Vintner’s Swan Marker with a swan at his feet. The Vintners’ are one of the twelve Great Livery Companies of the City of London and jointly, with the Dyers’ Livery Company and the Crown, they own the swans on the River Thames. Each July, during Swan Upping, the swans are marked or ringed. The Swan Marker wears the traditional Barge Master’s uniform.

Lions, Trafalgar Square

The fountains and Nelsons Column are guarded by Sir Edwin Landseer’s four great lions. They offer a popular spot for selfies today, with parents shoving their children up on to the pedestal for pictures and tourists clambered all over it. Although the square was later swamped by crowds of protestors, I did manage to complete my drawing in time before I went home.

Holborn Viaduct over the hidden River Fleet

Red and gold dragons guard the bridge, while the subterranean River Fleet flows beneath Holborn Viaduct to join the Thames at Blackfriars. Beyond is Smithfield Market which will become the site for the new London Museum.

Watergate Steps, Deptford

A cobbled dead end alley takes you to Watergate Steps and the river, where I was down on the shore by 7am to catch the low tide. Drawing with my back to the river, I was aware the tide had turned and the water was slowly creeping back up the beach, so I made a swift pencil sketch within the hour. Along the Thames, there were once many stairs and steps serving as points where watermen gathered in their boats to row passengers up, down or across the river. Watergate Steps would have been a landing for the ferry over to the Isle of Dogs.

Drawings copyright © Peta Bridle

You may also like to take a look at

Peta Bridle’s London Viewpoints

Peta Bridle’s East End Sketchbook

Peta Bridle’s Riverside Sketchbook

Peta Bridle’s Gravesend Sketchbook

Peta Bridle’s City of London Sketchbook

In Old Rotherhithe

Let me show you this 18th century graffiti on St Paul’s Cathedral…join my walk through the City of London. There are only two left this summer – Sunday 2nd July and Sunday 6th August at 2pm

Enjoy a storytelling ramble across the Square Mile, from the steps of St Paul’s through the narrow alleys and lanes to the foot of old London Bridge, in search of the wonders and the wickedness of the City of London.

Click here to book your tickets

St Mary Rotherhithe Free School founded 1613

To be candid, there is not a lot left of old Rotherhithe – yet what remains is still powerfully evocative of the centuries of thriving maritime industry that once defined the identity of this place. Most visitors today arrive by train – as I did – through the Brunel tunnel built between 1825 and 1843, constructed when the growth of the docks brought thousands of tall ships to the Thames and the traffic made river crossing by water almost impossible.

Just fifty yards from Rotherhithe Station is a narrow door through which you can descend into the 1825 shaft via a makeshift staircase. You find yourself inside a huge round cavern, smoke-blackened as if the former lair of a fiery dragon. Incredibly, Marc Brunel built this cylinder of brick at ground level – fifty feet high and twenty-five feet in diameter – and waited while it sank into the damp earth, digging out the mud from the core as it descended, to create the shaft which then became the access point for excavating the tunnel beneath the river.

It was the world’s first underwater tunnel. At a moment of optimism in 1826, a banquet for a thousand investors was held at the bottom of the shaft and then, at a moment of cataclysm in 1828, the Thames surged up from beneath filling it with water – and Marc’s twenty-two-year-old son Isambard was fished out, unconscious, from the swirling torrent. Envisaging this diabolic calamity, I was happy to leave the subterranean depths of the Brunels’ fierce imaginative ambition – still murky with soot from the steam trains that once ran through – and return to the sunlight of the riverside.

Leaning out precariously upon the Thames’ bank is an ancient tavern known as The Spread Eagle until 1957, when it was rechristened The Mayflower – in reference to the Pilgrims who sailed from Rotherhithe to Southampton in 1620, on the first leg of their journey to New England. Facing it across the other side of Rotherhithe St towers John James’ St Mary’s Rotherhithe of 1716 where an attractive monument of 1625 to Captain Anthony Wood, retrieved from the previous church, sports a fine galleon in full sail that some would like to believe is The Mayflower itself – whose skipper, Captain Christopher Jones, is buried in the churchyard.

Also in the churchyard, sits the handsome tomb of Prince Lee Boo. A native of the Pacific Islands, he befriended Captain Wilson of Rotherhithe and his two sons who were shipwrecked upon the shores of Ulong in 1783. Abba Thule, the ruler of the Islands, was so delighted when the Europeans used their firearms to subdue his enemies and impressed with their joinery skills in constructing a new vessel, that he asked them to take his second son, Lee Boo, with them to London to become an Englishman.

Arriving in Portsmouth in July 1784, Lee Boo travelled with Captain Wilson to Rotherhithe where he lived as one of the family, until December when it was discovered he had smallpox – the disease which claimed the lives of more Londoners than any other at that time. At just twenty years old, Lee Boo was buried inside the Wilson family vault in Rotherhithe churchyard, but – before he died – he sent a plaintive message home to tell his father “that the Captain and Mother very kind.”

Across the churchyard from The Mayflower is Rotherhithe Free School, founded by two Peter Hills and Robert Bell in 1613 to educate the sons of seafarers. Still displaying a pair of weathered figures of schoolchildren, the attractive schoolhouse of 1797 was vacated in 1939 yet the school may still be found close by in Salter Rd. Thus, the pub, the church and the schoolhouse define the centre of the former village of Rotherhithe with a line of converted old warehouses extending upon the river frontage for a just couple of hundred yards in either direction beyond this enclave.

Take a short walk to the west and you will discover The Angel overlooking the ruins of King Edward III’s manor house but – if you are a hardy walker and choose to set out eastward along the river – you will need to exercise the full extent of your imagination to envisage the vast vanished complex of wharfs, quays and stores that once filled this entire peninsular.

At the entrance to the Rotherhithe road tunnel stands the Norwegian Church with its ship weather vane

Chimney of the Brunel Engine House seen from the garden on top of the tunnel’s access shaft

Isambard Kingdom Brunel presides upon his audacious work

Visitors gawp in the diabolic cavern of Brunel’s smoke-blackened shaft descending to the Thames tunnel

John James’ St Mary’s Rotherhithe of 1716

The tomb of Prince Lee Boo, a native of the Pelew or Pallas Islands ( the Republic of Belau), who died in Rotherhithe of smallpox in 1784 aged twenty

Graffiti upon the church tower

Monument in St Mary’s, retrieved from the earlier church

Charles Hay & Sons Ltd, Barge Builders since 1789

Peeking through the window into the costume store of Sands Films

Inside The Mayflower

A lone survivor of the warehouses that once lined the river bank

Looking east towards Rotherhithe from The Angel

The Angel

The ruins of King Edward III’s manor house

Bascule bridge

Nelson House

Metropolitan Asylum Board china from the Smallpox Hospital Ships once moored here

Looking across towards the Isle of Dogs from Surrey Docks Farm

Take a look at

Adam Dant’s Map of Stories from the History of Rotherhithe

and you may also like to read

On Father’s Day

Click here to book your tour tickets for next Saturday and beyond

My father

On Sunday – when I was a child – my father always took me out for the morning. It was a routine. He led me by the hand down by the river or we took the car. Either way, we always arrived at the same place.

He might have a bath before departure and sometimes I walked into the bathroom to surprise him there lying in six inches of soapy water. Meanwhile downstairs, my mother perched lightly in the worn velvet armchair to skim through the newspaper. Then there were elaborate discussions between them, prior to our leaving, to negotiate the exact time of our return, and I understood this was because the timing and preparation of a Sunday lunch was a complex affair. My father took me out of the house the better to allow my mother to concentrate single-mindedly upon this precise task and she was grateful for that opportunity, I believed. It was only much later that I grew to realise how much she detested cooking and housework.

A mile upstream there was a house on the other riverbank, the last but one in a terrace and the front door gave directly onto the street. This was our regular destination. When we crossed the river at this point by car, we took the large bridge entwined with gryphons cast in iron. On the times we walked, we crossed downstream at the suspension footbridge and my father’s strength was always great enough to make the entire structure swing.

Even after all this time, I can remember the name of the woman who lived in the narrow house by the river because my father would tell my mother quite openly that he was going to visit her, and her daughters. For she had many daughters, and all preoccupied with grooming themselves it seemed. I never managed to count them because every week the number of her daughters changed, or so it appeared. Each had some activity, whether it was washing her hair or manicuring her nails, that we would discover her engaged with upon our arrival. These women shared an attitude of languor, as if they were always weary, but perhaps that was just how they were on Sunday, the day of rest. It was an exclusively female environment and I never recalled any other male present when I went to visit with my father on those Sunday mornings.

To this day, the house remains, one of only three remnants of an entire terrace. Once on a visit, years later, I stood outside the house in the snow, and contemplated knocking on the door and asking if the woman still lived there. But I did not. Why should I? What would I ask? What could I say? The house looked blank, like a face. Even this is now a memory to me, that I recalled once again after another ten years had gone by and I glanced from a taxi window to notice the house, almost dispassionately, in passing.

There was a table with a bench seat in an alcove which extended around three sides, like on a ship, so that sometimes as I sat drinking my orange squash while the women smoked their cigarettes, I found myself surrounded and unable to get down even if I chose. At an almost horizontal angle, the morning sunlight illuminated this scene from a window in the rear of the alcove and gave the smoke visible curling forms in the air. After a little time, sitting there, I became aware that my father was absent, that he had gone upstairs with one of the women. I knew this because I heard their eager footsteps ascending.

On one particular day, I sat at the end of the bench with my back to the wall. The staircase was directly on the other side of this thin wall and the women at the table were involved in an especially absorbing conversation that morning, and I could hear my father’s laughter at the top of the stairs. Curiosity took me. I slipped off the bench, placed my feet on the floor and began to climb the dark little staircase.

I could see the lighted room at the top. The door was wide open and standing before the end of the bed was my father and one of the daughters. They were having a happy time, both laughing and leaning back with their hands on each other’s thighs. My father was lifting the woman’s skirt and she liked it. Yet my presence brought activities to a close in the bedroom that morning. It was a disappointment, something vanished from the room as I walked into it but I did not know what it was. That was the last time my father took me to that house, perhaps the last time he visited. Though I could not say what happened on those Sunday mornings when I chose to stay with my mother.

We ate wonderful Sunday lunches, so that whatever anxiety I had absorbed from my father, as we returned without speaking on that particular Sunday morning, was dispelled by anticipation as we entered the steamy kitchen with its windows clouded by condensation and its smells of cabbage and potatoes boiling.

My mother was absent from the scene, so I ran upstairs in a surge of delight – calling to find her – and there she was, standing at the head of the bed changing the sheets. I entered the bedroom smiling with my arms outstretched and, laughing, tried to lift the hem of her pleated skirt just as I saw my father do in that other house on the other side of the river. I do not recall if my father had followed or if he saw this scene, only that my mother smiled in a puzzled fashion, ran her hands down her legs to her knees, took my hand and led me downstairs to the kitchen where she checked the progress of the different elements of the lunch. For in spite of herself, she was a very good cook and the ritual of those beautiful meals proved the high point of our existence at that time.

The events of that Sunday morning long ago when my father took me to the narrow house with the dark staircase by the river only came back to me as a complete memory in adulthood, but in that instant I understood their meaning. I took a strange pleasure in this knowledge that had been newly granted. I understood what kind of house it was and who the “daughters” were. I was grateful that my father had taken me there, and from then on I could only continue to wonder at what else this clue might reveal of my parents’ lives, and of my own nature.

Me and my father

You may also like to read about

James Boswell’s East End

Click here to book your tour tickets for this Saturday and beyond

A few years ago, I visited a leafy North London suburb to meet Ruth Boswell – an elegant woman with an appealing sense of levity – and we sat in her beautiful garden surrounded by raspberries and lilies, while she told me about her visits to the East End with her late husband James Boswell who died in 1971. She pulled pictures off the wall and books off the shelf to show me his drawings, and then we went round to visit his daughter Sal who lives in the next street and she pulled more works out of her wardrobe for me to see. And when I left with two books of drawings by James Boswell under my arm as a gift, I realised it had been an unforgettable introduction to an artist who deserves to be better remembered.

From the vast range of work that James Boswell undertook, I have selected these lively drawings of the East End done over a thirty year period between the nineteen thirties and the fifties.There is a relaxed intimate quality to these – delighting in the human detail – which invites your empathy with the inhabitants of the street, who seem so completely at home it is as if the people and cityscape are merged into one. Yet, “He didn’t draw them on the spot,” Ruth revealed as I pored over the line drawings trying to identify the locations, “he worked on them when he got back to his studio. He had a photographic memory, although he always carried a little black notebook and he’d just make few scribbles in there for reference.”

“He was in the Communist Party, that’s what took him to the East End originally,” she continued, “And he liked the liveliness, the life and the look of the streets, and and it inspired him.” In fact, James Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 after graduating from the Royal College of Art and his lifelong involvement with socialism informed his art, from drawing anti-German cartoons in style of George Grosz during the nineteen thirties to designing the posters for the successful Labour Party campaign of 1964.

During World War II, James Boswell served as a radiographer yet he continued to make innumerable humane and compassionate drawings throughout postings to Scotland and Iraq – and his work was acquired by the War Artists’ Committee even though his Communism prevented him from becoming an official war artist. After the war, as an ex-Communist, Boswell became art editor of Lilliput influencing younger artists such as Ronald Searle and Paul Hogarth – and he was described by critic William Feaver in 1978 as “one of the finest English graphic artists of this century.”

Ruth met James in the nineteen-sixties and he introduced her to the East End. “We spent quite a bit of time going to Blooms in Whitechapel in the sixties. We went regularly to visit the Whitechapel when Robert Rauschenberg and the new Americans were being shown, and then we went for a walk afterwards,” she recalled fondly, “James had been going for years, and I was trying to make my way as a journalist and was looking at the housing, so we just wandered around together. It was a treat to go the East End for a day.”

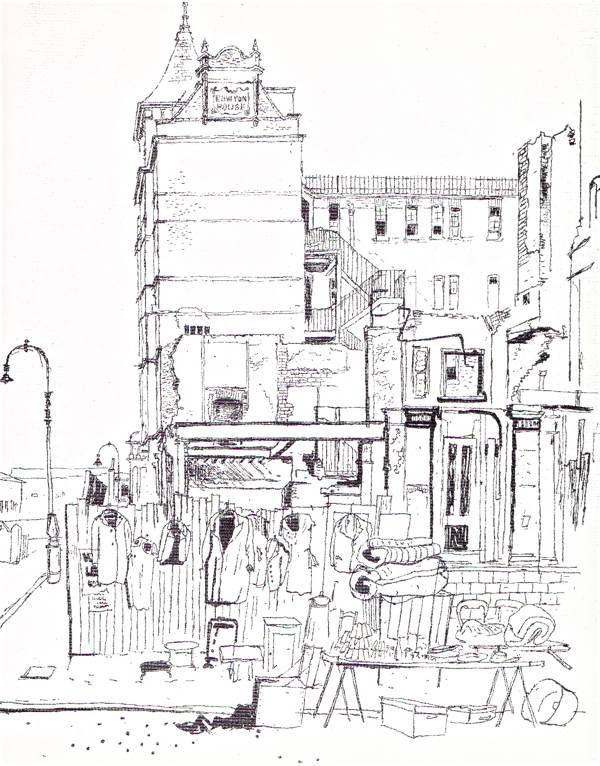

Rowton House

Old Montague St, Whitechapel

Gravel Lane, Wapping

Brushfield St, Spitalfields

Wentworth St, Spitalfields

Brick Lane

Fashion St, illustration by James Boswell from “A Kid for Two Farthings” by Wolf Mankowitz, 1953.

Russian Vapour Baths in Brick Lane from “A Kid for Two Farthings.”

James Boswell (1905-1971)

Leather Lane Market, 1937

Images copyright © Estate of James Boswell

You might also like to take a look at

In the footsteps of Geoffrey Fletcher

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part One)

The Spitalfields Nobody Knows (Part Two)

Adverts From The Jewish East End

Click here to book your tour tickets for this Saturday and beyond

Stefan Dickers, Archivist at Bishopsgate Institute showed me these adverts he found in an almanac from 1925 that originally came from Sandys Row Synagogue, evoking a lost East End world of Kosher Viands, Lodzer Cakes and Keating’s Powder.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to take a look at

Adverts from Stepney Borough Guide