Marcellus Laroon’s Cries Of London

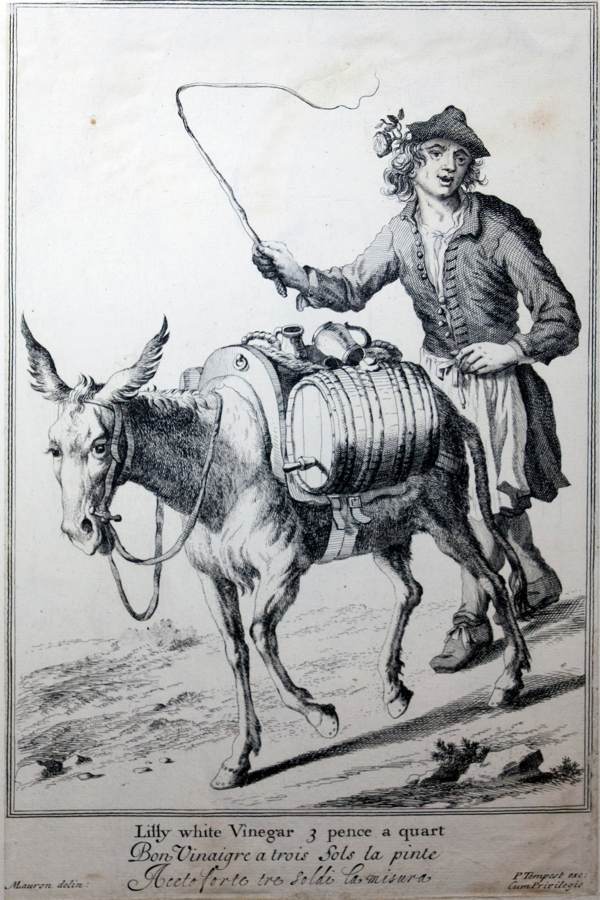

Today it is my pleasure to publish Marcellus Laroon’s vibrant series of engravings of the Cries of London reproduced from an original edition of 1687 in the collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

The death of Oliver Cromwell and the restoration of Charles II made the thoroughfares of London festive places once again, renewing the street life of the metropolis. After the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed the shops and wiped out most of the markets, an unprecedented horde of hawkers flocked to the City from across the country to supply the needs of Londoners .

Samuel Pepys and Daniel Defoe both owned copies of Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London. Among the very first Cries to be credited to an individual artist, Laroon’s “Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life” were on a larger scale than had been attempted before, which allowed for more sophisticated use of composition and greater detail in costume. For the first time, hawkers were portrayed as individuals not merely representative stereotypes, each with a distinctive personality revealed through their movement, their attitudes, their postures, their gestures, their clothing and the special things they sold. Marcellus Laroon’s Cries possessed more life than any that had gone before, reflecting the dynamic renaissance of the City at the end of the seventeenth century.

Previous Cries had been published with figures arranged in a grid upon a single page, but Laroon gave each subject their own page, thereby elevating the status of the prints as worthy of seperate frames. And such was their success among the bibliophiles of London, that Laroon’s original set of forty designs – reproduced here – commissioned by the entrepreneurial bookseller Pierce Tempest in 1687 was quickly expanded to seventy-four and continued to be reprinted from the same plates until 1821. Living in Covent Garden from 1675, Laroon sketched his likenesses from life, drawing those he had come to know through his twelve years of residence there, and Pepys annotated eighteen of his copies of the prints with the names of those personalities of seventeenth century London street life that he recognised.

Laroon was a Dutchman employed as a costume painter in the London portrait studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller – “an exact Drafts-man, but he was chiefly famous for Drapery, wherein he exceeded most of his contemporaries,” according to Bainbrigge Buckeridge, England’s first art historian. Yet Laroon’s Cries of London, demonstrate a lively variety of pose and vigorous spontaneity of composition that is in sharp contrast to the highly formalised portraits upon which he was employed.

There is an appealing egalitarianism to Laroon’s work in which each individual is permitted their own space and dignity. With an unsentimental balance of stylisation and realism, all the figures are presented with grace and poise, even if they are wretched. Laroon’s designs were ink drawings produced under commission to the bookseller and consequently he achieved little personal reward or success from the exploitation of his creations, earning his living by painting the drapery for those more famous than he and then dying of consumption in Richmond at the age of forty-nine. But through widening the range of subjects of the Cries to include all social classes and well as preachers, beggars and performers, Marcellus Laroon left us us an exuberant and sympathetic vision of the range and multiplicity of human life that comprised the populace of London in his day.

Images photographed by Alex Pink & reproduced courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Peruse these other sets of the Cries of London I have collected

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

William Nicholson’s London Types

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

More of Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Adam Dant’s New Cries of Spittlefields

I was intrigued by “New River Water” – as opposed to “Old” river water. It made me very thankful that I can turn on a tap in my home and enjoy wonderful clean water, yet also made me think how I take that for granted. Sadly for many millions throughout the world “new” or “old” river water is all they have. It has prompted me to donate to water aid charity. Thank you GA.

These are great – full of character and interesting details. And I love that some are drawn from behind so that we can see all the gubbins that they are carrying.

However the stand out character of this set has to be the Famous Dutch Woman – one needs to know more!

Wonderful ! Wonderful. ! What a difference in then and now in as much that which we take for granted, such as water for instance. These London characters worked hard for a pittance but they seemed to look happy just the same. Thank you for such an interesting post.

Mary, the ‘new’ goes with the river rather than the water. The New River was an artificial construction created in the early C17th to channel fresh spring and river water through London from sources to the north and west of it. It was extremely important for the health and survival of the population and parts of it are still in use today. Others know far more about it than I do, but there’s an interesting article on Wikipedia to get you started. I can’t of course vouch for the contents of the water carrier’s barrels nor how clean he kept them!

Thanks Ros,I had never heard of New River. The Wikipaedia entry is very interesting especially as the river it is still used for supplying water to London’s population. At least some good came out of my misunderstanding. G.A’s blog is always an education!

Wonderful Painting of this Vintage Lives.???????