John Minton’s East End

Martin Salisbury author of The Snail that climbed the Eiffel Tower, a monograph of John Minton’s graphic work, explores Minton’s fascination with the East End.

Never quite accepted by the establishment during his brief, rather tragic life, artist John Minton (1917—1957) has divided opinion ever since. Brilliant illustrator, inspirational teacher, prodigious habitué of Soho and Fitzrovia drinking establishments, Minton was bound to enter the folklore of post-war London. Somehow, he embodied the mood of elegiac romanticism that pervaded the arts through the forties and into the early fifties before fizzling out to be replaced by a more forward-looking, assertive art in the form of American abstract expressionism and British ‘kitchen-sink’ realism.

His life, riddled as it was with contradictions, began on Christmas Day 1917 in a wooden house near Cambridge, of an architectural style that some have termed ‘Gingerbread,’ and ended just under forty years later in Chelsea. He had apparently taken his own life.

This year’s centenary of Minton’s birth bring recognition to an artist who has not previously enjoyed the attention that has come the way of those other mid-century greats, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and John Piper. An exhibition at Pallant House, Chichester this summer gathered many of his paintings that have received mixed responses over the years. Rooms were devoted to his portraits, his various epic narrative paintings and his neo-romantic landscapes. Alongside his ‘longing to be away’ paintings of Corsica, Jamaica and Spain, there were also many depictions of London. In particular, it was London’s dockland that he returned to repeatedly.

Arguably, John Minton was at his best as a graphic and commercial artist, perhaps best known for his sublime illustrations for publisher John Lehmann to Elizabeth David’s highly influential food writing and Alan Ross; Corsica travel journal, Time Was Away, a lavish anti-austerity production. Yet Minton’s urban romanticism found its way into many commercial commissions too. Wartime drawings of bombed-out buildings in Poplar still exhibited the samr overwrought theatricality that was a feature of his work while under the spell of friend and fellow artist, Michael Ayrton.

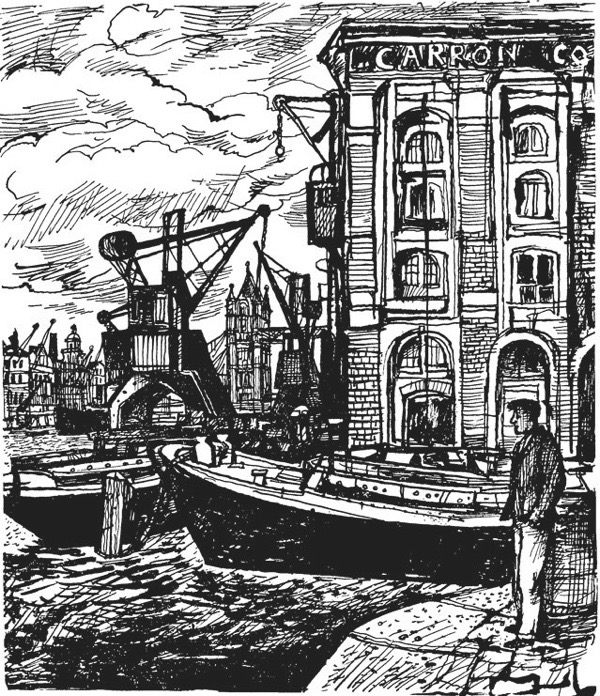

In the immediate post-war years, as Minton’s work drew more consistently on direct observation, his visual vocabulary matured and his frequent visits to the river resulted in a mass of drawings of the cranes and wharves of the Port of London and Bankside. Rotherhithe from Wapping was painted in 1946 and a three-colour lithograph of the same composition followed two years later, renamed Thames-side.

The flattened perspective in this pictures embraces barges in the foreground and the jumble of warehouses on the far bank in the background. Typically, this image includes a pair of male figures in intimate conversation. Minton’s sexuality was central to his work and these dockland images embody the frustration he felt as a gay man at a time when sex between men was illegal. The many hours that Minton spent haunting the riverside allowed him not only to draw but to enjoy the company of sailors and dockers. Time and again, his pictures feature solitary male figures or distant pairs, huddled together, walking at low tide or working on boats, dwarfed by the surrounding buildings and brooding clouds.

John Minton’s only commission for London Transport came from publicity officer, Harold F. Hutchison in the form of a ‘pair poster’ titled London’s River. This concept involved posters designed in adjoining pairs, with one side featuring a striking pictorial image and the other containing text. The familiar dockland images are reworked here in gouache, in similar manner to the series of paintings commissioned for Lilliput in July 1947, London River.

An unpublished rough cover design for The Leader magazine executed in 1948 features another of Minton’s favourite motifs, the elevated street view. In this instance, the foreground figure gazing from an upper window bears more than a passing resemblance to the artist himself. The composition takes us beyond the streets below to the Thames via the dome of St Paul’s. A similar view, this time of the author’s native Hackney, graces the dust jacket of Roland Camberton’s Rain on the Pavements, published in 1951 by John Lehmann. This was the second of Camberton’s two novels, both with dust jackets designed by Minton, and tells the story of David Hirsch’s early years growing up in Hackney Jewish society.

In his 2008 article Man in a MacIntosh, Iain Sinclair followed in the footsteps of a fellow Hackney writer, recognising, “Camberton, in choosing to set ‘Rain on the Pavements’ in Hackney, was composing his own obituary. Blackshirt demagogues, the spectre of Oswald Mosley’s legions, stalk Ridley Rd Market while the exiled author ransacks his memory for an affectionate and exasperated account of an orthodox community in its prewar lull.”

John Minton’s magnificent jacket design draws us into that world with effortless elegance.

Rain on the Pavements, 1951

Scamp, 1950

Wapping, 1941

Bomb-damaged buildings, Poplar, 1941

Rotherhithe from Wapping, 1946

London Bridge from Cannon Street Station, 1946

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

London’s River, Lilliput 1947

Illustrations from Flower of Cities, 1949

London’s River: Pool of London, London Transport, 1951

The Leader, 1948

Isle of Dogs from Greenwich, 1955

Illustrations copyright © Estate of John Minton

You may also like to read about Alfred Daniels & Terry Scales who were taught by John Minton

John Minton a much overlooked artist and illustrator. The excellent exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery recently featured many of his paintings and book covers. Many thanks for the article and heads up about the new publication featuring his work.

This lovable culture of the East End goes on through the the pen of GA. there is a big dash for colour today which brightens up this Nov day. John’s work is just gorgeous the Lilliput pic I like features the dominant St Paul’s. His work does typify the London scene at that time in the 1940-50’s a nice one Martin. John a bus pass poet

He was a very talented painter. Valerie

I’ve been a Minton admirer since about 1966 when I saw “ Street Scene in South London” at the Tate. The shapes, and especially the colours , knocked me out. When I did my Fine Art degree at Portsmouth College of Art, I was delighted to find that the Head of Painting was Richard Crabbe, who had been taught by John Minton at the RCA. My degree thesis was therefore on the subject of John Minton, and I have been going on about him ever since. Eric Ravilious was under-rated until recently. Now, surely, it is the turn of John Minton to enjoy some posthumous celebrity.

How tragic this talented individual took his own life. I could recognise some of these scenes Greenwich across to the Isle of Dogs and the river near where the Millennium Bridge is today.

Greetings from Boston,

GA, thanks for sharing the wonderful work of John Minton. I particularly liked the colors and angles in London’s River: Pool of London, London Transport, 1951.

What a shame that Minton chose to end his own life at such an early age…

Kismet! I came across a magazine tear sheet with John Minton’s painting of London Bridge, without an artist attribution, and immediately saved it for my visual archive. I love the surprising composition, and the unique portrayal of the location, etc.

After seeing additional work today, and hearing his story, I look forward to receiving the book

about this very gifted artist.

Many of the artists you have mentioned….Alfred Daniels, Piper, Bawden, others……are favorites of mine, and now I can happily add the name of John Minton.

Thanks for shining a light, GA.

I have always been a great admirer of |John Minton’s work, and I like everything about them, the black and white illustrations, the wonderful use of colour and the flattened perspective and, especially, the dust jackets. He, together with his contemporary, Richard Chopping, are sadly very much overlooked now although Dick did gain recognition for his wonderful dust jackets that he did for the Ian Fleming James Bond books. It is so sad that John Minton possibly took his own life but it was very hard for gay men then, Dick once told me that he would have given anything not to have been born as he was.

Always had a soft spot for Minton.Re-reading Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore at the moment. His Thames scenes so evocative of that book.