So Long, Grace Payne

City of London resident Grace Payne died on 16th December aged 101. As a tribute, I am republishing novelist Sarah Winman‘s interview with Grace.

Grace Payne (1924-2025)

I was looking out from the thirty-sixth floor of one of the Barbican Towers. The clouds were low, and the City was trapped beneath a dismal fug. The spire of Christ Church, Spitalfields, was barely visible in the distance.

“You used to be able to see the Monument from here, but now it’s dwarfed by all the towers. Nothing is as it was, except perhaps the Honourable Artillery Company ground,” said Grace, as she placed the tea tray down and offered me a delicious homemade flap jack. “Not that everything in the past is necessarily good. If you go back far enough, it becomes a hell of a lot worse.”

“My Granny had four children and her husband died of consumption. Died like flies from overcrowding then. Mummy was only six. Granny ended up living in the Corporation Buildings in Farringdon Road – The old Guardian home – There was one parlour, one bedroom and a scullery with a copper pot, and a loo out the back. I can still smell the linoleum in that parlour.”

I had known the ubiquitous Grace Payne for five years then. We sang in a Community Choir together and the first things I noticed about her were her style, her elegance, and her irrepressible vitality. Over time I’d got to know a little about her working life, her sixteen years spent in Hong Kong, a little about her family. But that afternoon, over a pot of tea, she took me back to a time before.

“I was born in 1924. We lived in a condemned tenement building in Brixton,” she told me. “My father was in the police there. We then moved to Streatham and I went to Sunnyhill Primary School – think it’s still there actually. In 1934, my father was made Chief Inspector of a division at the Minories and we lived at the police station at number sixty. If you look for it now, it’s just a highway. I took a junior county scholarship for the City of London School for Girls, which was in Carmelite Street then. The headmistress was a Miss Turner: a slim woman, hair in a bun, flat buttoned shoes, dressed in purple, you know the type. Wouldn’t allow a book to be placed on top of the bible in her presence! It was quite a snobby environment, and I had rather a South London accent. My mother, a working class woman, went to meet Miss Turner and was asked, ‘What would happen about the fees if your husband lost his job?’ So insensitive. They recommended me to have elocution lessons.”

“I used to travel from Mark Lane Station (now Tower Hill) to Blackfriars. There were no school friends or neighbours who lived near me, except my friend Olga Raphalowsky who lived in Spitalfields. They were White Russian Refugees. Her father was a GP and they lived over the surgery. This family was like another world to me. Thick accents, intellectuals, wonderful and friendly – so exotic, not at all English. Uncle Danny was a film maker! I was still friends with Olga up until she died two years ago.”

“Oh I’ve stayed in touch with many of my school friends – Margaret and Mary, and Hazel Morris. I suppose wartime brought us together. In November 1940 we were evacuated to Keighley in Yorkshire. We waited in the church hall for one’s name to be called out and for someone to take you home. Margaret and I were billeted together with a family called Lumb. We were there for two years with the mother and father and three year old Jean. Well, Jean comes to stay with us now when she comes to London. She must be nearly seventy-three.”

“Keighley was grim. War was pretty bad by then and rationing tight. Coal was in short supply and homes were cold. But Margaret and I used to go into Bradford for the Hallé concerts. Henry Wood was conducting one night and he apologised for wearing a lounge suit. He explained that his suitcase had been lost on the train and that’s why he didn’t have his proper dress.”

“Before evacuation, however, we’d gone to live in Snow Hill police station because my father had again been promoted. He was in charge of all the ARP warden’s too. There was sticky tape across the bow windows and sandbags piled out the front. The police station had a flat roof and I used to collect shrapnel that had fallen during the night. I had a great collection. One morning, I found cans of fruit on the roof that had blown over from an exploding warehouse. I used to sleep in the basement and my parents slept at the back. A bomb fell on our building in September 1940. It was 10:30, 11:15 at night, I think. Four bombs were dropped all in a line – one hit the Evening Standard building, another St Bart’s hospital, another I can’t remember, but the last fell on us. I remember my parents coming out covered in dust.”

“From my school days until now, the one thing I’ve always done is sing in a choir – maybe with a few gaps. But my father always sang in a choir. He started the City of London Police Choral Society, started it during the war. He sang at Douglas’s and my wedding. We were married in St Bartholomew the Great Church. It was wonderful, didn’t cost an arm and a leg in those days – The film “Four Weddings and a Funeral” changed all that. Cost us seven shillings and sixpence, I think.”

“We didn’t consciously move back to the Barbican after our travels. We were living in South Kensington. But when we got to the age of seventy, we were nagged by one of our daughters to move before one of us had a stroke or something! But I can’t imagine not living here. At our age there’s so much to do. If we lived in the country what the hell would we do?”

There was a moment to pause, and I wrote: City of London Old Girl, Imperial College Old Girl, wife, mother, university teacher, text book writer, traveller, jewellery maker, and all round good egg.

“Anything else, Grace?” I asked.

“Grandmother and great grandmother,” she said. “Family, it’s the thing that matters most of all. Everything else is rather trivial in comparison,” she said and she smiled. And I know she was right.

I looked up from my notebook and realized hours had passed. Night had fallen. We sat quietly as lights erupted across the spent City.

“I was also a model, you know,” said Grace matter-of-factly.” Must have been seven because after that I cut my hair and they didn’t want me then. I modelled for a Couture House in Bond Street – ‘Russell and Allen’s’ – I came up on the tram from Streatham, lovely to have a day off school. Also modelled for Paton and Baldwins’ knitting patterns.”

I took another succulent flap jack. I was happy. Grace Payne I salute you.

Home made flapjacks following a sixty year old recipe.

Grace’s first teddy bear.

Grace in her kitchen jewellery workshop.

Grace in her modelling days.

Grace at the Police Sports Day around 1930.

At Sunny Hill Road Primary School.

Grace’s father

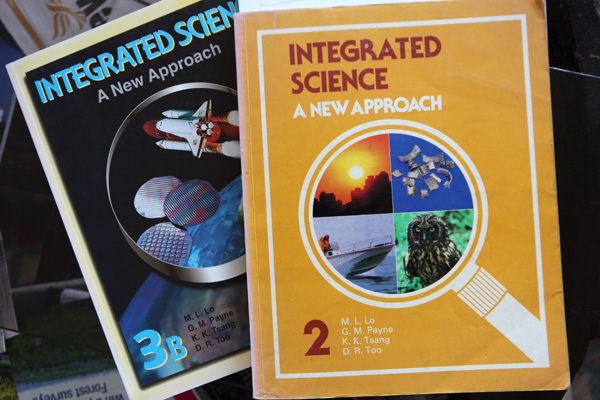

Science text books from Hong Kong co-written by Grace.

Grace Payne

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

What an amazing lady. It must have been a priviledge to have known her. Rest in peace Grace.

A light emanates from her. In the photograph of her and her classmates, in the days before people typically smiled in photographs, she’s smiling.

This piece calls up a world that is almost completely gone. Soon all the personal accounts of wartime England will come to an end. Her memory of going up to the flat roof to collect the shrapnel from the night before is extraordinary to a modern-day reader; I don’t think I’ll ever forget this: “One morning, I found cans of fruit on the roof that had blown over from an exploding warehouse.”

Thank you, GA, and RIP Grace Payne

What a wonderful story, what a wonderful woman. At 101 years old, she certainly had a long and fulfilling life. — My first teddy bear sits with me on my sofa. And Grace’s is now all alone. Oh, if only I could adopt that old English bear!

Dear GRACE PAYNE (1924-2025) – R.I.P.

Love & Peace

ACHIM

What a beautiful interview (I love all of Sarah Winman’s writing) and what an amazing life Grace lived. Rest in Peace.

Not forgetting Patrica Niven’s beautiful portraits!

A marvelous, smart and brilliant lady !! She created a great life and seemed a happy kind and loving soul.

Proud of whom she was and kind to others. Plus at 101 YEARS OLD SHE STILL HAD HER OWN TEETH.. Even in midst of War all around them..she found joy and friends..

Thank you for sharing her life with us. And thank you for photos ..it always touches my heart. to see face of people..

Thank you

Debra

Grace Payne. The title jumped out, hoping this admired, intrepid character might be a relative. Payne by marriage to Dr Douglas Sutherland Payne of the Royal College of Science, also much respected and mourned by his colleagues. Wonderful to be married at St Bartholomew the Great in the tangible historic atmosphere of Smithfields.

My great grandmother was Mary Ann Hannah PAYNE christened in Schroedinger’s church St Leonard’s, Shoreditch in 1840. Born Mile End. I went to find their addresses, sadly demolished.

Some time after his very fortunate adoption, l went to stand on those well worn church flagstones where both Shroedinger wandered and my Great Great Grandparents had held their small baby at the baptism.

RIP dear Grace RIP dear Shroedinger Epiphany 2026

I only had the pleasure of meeting Grace a handful of times but that was enough to know what a remarkable a lady she was.

This was an incredible piece which was a delight to read, thank you.

Rest in peace Grace x