Lorna Brunstein Of Black Lion Yard

Click here to book your ticket for THE GENTLE AUTHOR’S TOUR OF SPITALFIELDS this Saturday

Lorna with her mother Esther in Whitechapel, 1950

In this photograph, Lorna Brunstein is held by her mother outside Fishberg’s jewellers on the corner of Black Lion Yard and Whitechapel Rd. It is a captivating image of maternal pride and affection that carries an astonishing story. The tale this tender photograph carries is one of how this might never have happened and yet, by the grace of fortune, it did.

I met Lorna upon her return visit to Whitechapel where she grew up the early fifties. Although she left Black Lion Yard at the age of six, it is a place that still carries great meaning for her even though it was demolished forty years ago.

We sat together in a crowded cafe in Whitechapel but, as Lorna told me her story, the sounds of the other diners faded out and I understood why she carries such affection for a place that no longer exists beyond the realm of memory.

“My relationship with the East End goes back to when I was born. I have scant memories, it was the early years of my childhood, but this was the area where I spent the first six years of my life. I was born in Mile End maternity hospital in December 1950.

Esther, my mother came to London in 1947. She was liberated from Belsen in April 1945 and she stayed in their makeshift hospital to recuperate for a few months. She had been through Auschwitz and lost all her family, apart from one brother who survived (though she did not know it at the time).

In the summer of 1945 she was taken to Sweden, to a place she said was beautiful – in the forest – where she and many others were looked after. It was while she was in Sweden that she and her brother Perec discovered via the Bund ( Polish Jewish workers Socialist party) that they had both survived. Esther was the youngest of three and Perec was the middle child. Their surname was Zylberberg, which means silver mountain. He was one of the boys who was taken to Windermere from Theresienstadt at the end of the War. They each wrote letters and confirmed that the other had survived. Esther had last seen Perec in March 1944.

After a few months in Windermere, he went to London and his sole mission was to get Esther over. That was all she wanted to do too, but it took two years from 1945 to 1947 for a visa to be granted. So not much has changed really. She was seventeen years old, had lost her mother at Auschwitz and her teenage years yet she was not allowed to come into the country unless she had a job, an address, and the name of a British citizen to be her guarantor and sponsor.

Maurice Regen (Uncle Moishe as I knew him) was an eccentric yet kind man. He came to London in the twenties from Lodz, which was my mother’s hometown. He and his wife were elderly, they had no children and lived in Romford. He said, ‘She can live in our house, so she will have an address, and she can be our housekeeper, that will be her job, and she won’t be dependent on the state.’ That was how my mother came over. My Uncle Perec met her and I think Uncle Moishe was probably there at Tilbury too.

She lived in Romford but she met Stan, my father, at the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre in Whitechapel where she was acting — her Yiddish was brilliant – and he was the scenic designer. He was an artist from Warsaw. He fled at the beginning of the War and was put in a labour camp in Siberia after spending fourteen months of solitary confinement in a prison in the Soviet Union. His story was pretty horrific too. He was an only child, and he lost everyone, his entire family. He was thirteen years older than my mother.

Stan also came to London in 1947. At the end of the War, he ended up in Italy. The Hitler/Stalin pact was broken while he was in Siberia and he was freed when the political amnesty was declared, so he joined up with the Polish Free Army under General Anders — as many of them did — and fought at the Battle of Monte Casino. Afterwards, he was in Rome for two years, studying scenic design at the Rome Academy of Fine Arts.

So my mother and father met in 1947 or 1948. I do not know exactly when. They got married in 1949 and I was born in 1950. They lived in a little flat in Black Lion Yard in Whitechapel until they moved to Ilford.

Rachel Fishberg – known as Ray – was really significant in my life and my parents’ life, my mother in particular. Ray was an old lady who became a surrogate grandma to my sister – who is four years younger – and me. We remember her with such affection. The Fishbergs were jewellers and were reasonably wealthy among Jewish people in the East End at that time. Ray ran her husband’s and his father’s jewellery shop, on the corner of Whitechapel Road and Black Lion Yard. I remember going back and visiting it when I was six, after we moved out.

My parents had no money, so grandma Ray Fishberg said they could live in the flat above the shop. At the time, they had nothing. My father could not live on his art and he took a diploma in design, tailoring and cutting at Sir John Cass School of Art in Aldgate. He designed and made children’s clothes on a sewing machine in the room we lived in and sold them in the market, and that was how we got by. Grandma Ray let them live there – probably for nothing – and, in fact, she paid for their wedding. When they got married in 1949 in Willesden Green, she paid for the wedding dress.

In 1957, when I was six, we moved to Ilford because my parents did not want to stay in the East End. She gave them the deposit for their first house. She was a lovely lady and she enabled them to have a start a life. This is why I feel so connected to this place, even though my memories of actually living here are scant.

I have this one memory of being in a pram, or maybe a pushchair, and feeling the sensation of the wheels on the cobbles in Black Lion Yard, going to the dairy — my mother said it was Evans the Dairy at the end of the Yard — to get milk.

Apparently, I went Montefiore School in Hanbury Street and I remember my mother talking about Toynbee Hall, where there were meetings, and taking me in the pram to Lyons Corner House in Aldgate where there was this chap, Shtencl, the poet of the East End.

He was quite an eccentric person who wandered around the streets and my mother told me he called into Lyons Corner House when she was sitting there with me as a baby. She said he stroked my head and said, ‘Sheyne, sheyne,’ which in Yiddish is ‘beautiful.’ My mother was in awe of him because his Yiddish was so brilliant and Yiddish was the language so dear to her heart. I was anointed by him even though I have no memory of him.

My mother and father talked a lot about Black Lion Yard. They said, on Sunday mornings at the entrance to Black Lion Yard where the pavement was quite deep, employers and potential employees in the tailoring ‘shmatte’ trade would gather and connect. That was what my father was doing then. He would stand there on a Sunday morning to get work.

Those were the founding years of my life. I have a deep affection for this place because for my parents – even though they wanted to leave for a better life – it was where they found sanctuary. My father used to say, ‘Thank goodness I’m here, I’ve finally found a place where I am able to walk down the street without having to look over my shoulder.”

Black Lion Yard, early seventies, by David Granick

Steps down to Black Lion Yard by Ron McCormick

Lorna aged eight

Esther & Stan Brunstein in the seventies

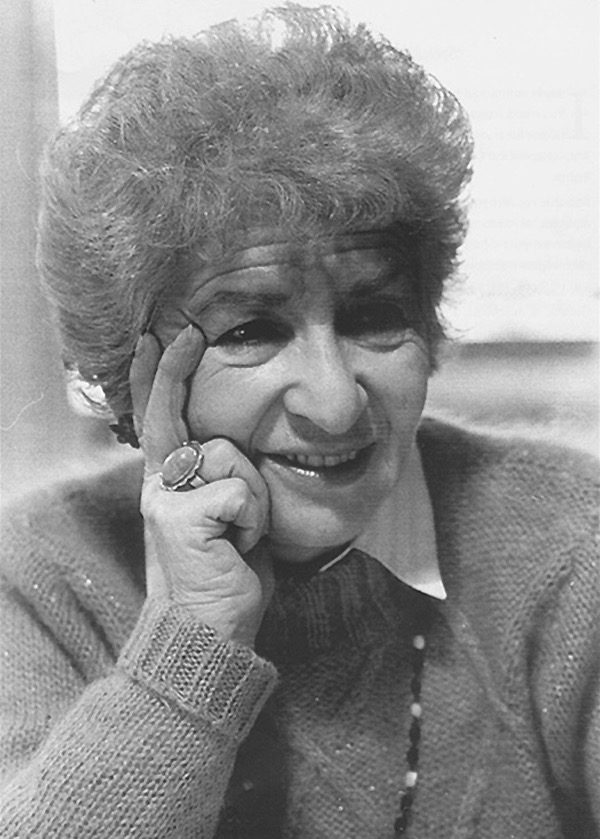

Esther Brunstein

Stan Brunstein

You may also like to read about

First of all – and I am sure others would say this too – Lorna, what a beautiful child you were! I’m sure, like your mother, you also turned into a very attractive woman 🙂

I just finished reading a book called “The Montreal Schtetl”, which was about what happened when Holocaust survivors moved to Montreal after the war. (I was born in 1950 and grew up in a very Jewish area of Montreal, where a WASP like me was a bit uncommon.) I was horrified to discover that (1) the Canadian government refused to allow any Jewish WWII refugees into Canada until about 1947, basically leaving them to die in the camps and (2) when the survivors finally did arrive, they were often treated badly by the more established Jewish community, some of who were suspicious of the survivors, believing they must have collaborated with the Nazis in order to survive. I can see that Jewish Canadians might have been traumatized by losing their own relatives during the war, but what a terrible thing to do to the survivors. I do hope the same thing did not happen in England.

A detailed story whose common denominator was Ray who helped us stay alive .

Our Ray was Rachel Cohen and may her soul rest in peace .

Thank you for sharing the story of Lorna Brunstein and her family. It’s so important we never forget, and horrific that it’s always been so difficult for those fleeing persecution to settle in this country. I’m so glad Ray helped Lorna’s parents settle and build a life together.

“I wear the key of memory, and can open every door in the house of my life.” – Amelia Barr

Thank you for these vivid recollections. I often think stories are the only thing keeping

the world intact. The kindness and humanity of Ray….. And the intrepid loving spirit of Esther and Stan…. and their surroundings in Black Lion Yard…… the preservation of a disappearing lanugage………. stories of optimism and triumph. So much to think about.

Onward and upward.

A moving story. Thank you

Stories of War and especially those dreadful years of Auschwitz and other concentration camps still move me to tears.