The Secrets Of Christ Church

There is a such a pleasing geometry to the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, Spitalfields, completed in 1729, that when you glance upon the satisfying order of the facade you might assume that the internal structure is equally apparent. Yet it is a labyrinth inside. Like a theatre, the building presents a harmonious picture from the centre of the stalls, yet possesses innumerable unseen passages and rooms, backstage.

Beyond the bellringers’ loft, a narrow staircase spirals further into the thickness of the stone spire. As you ascend the worn stone steps within the thickness of the wall, the walls get blacker and the stairs get narrower and the ceiling gets lower. By the time you reach the top, you are stooping as you climb and the giddiness of walking in circles permits the illusion that, as much as you are ascending into the sky, you might equally be descending into the earth. There is a sense that you are beyond the compass of your experience, entering indeterminate space.

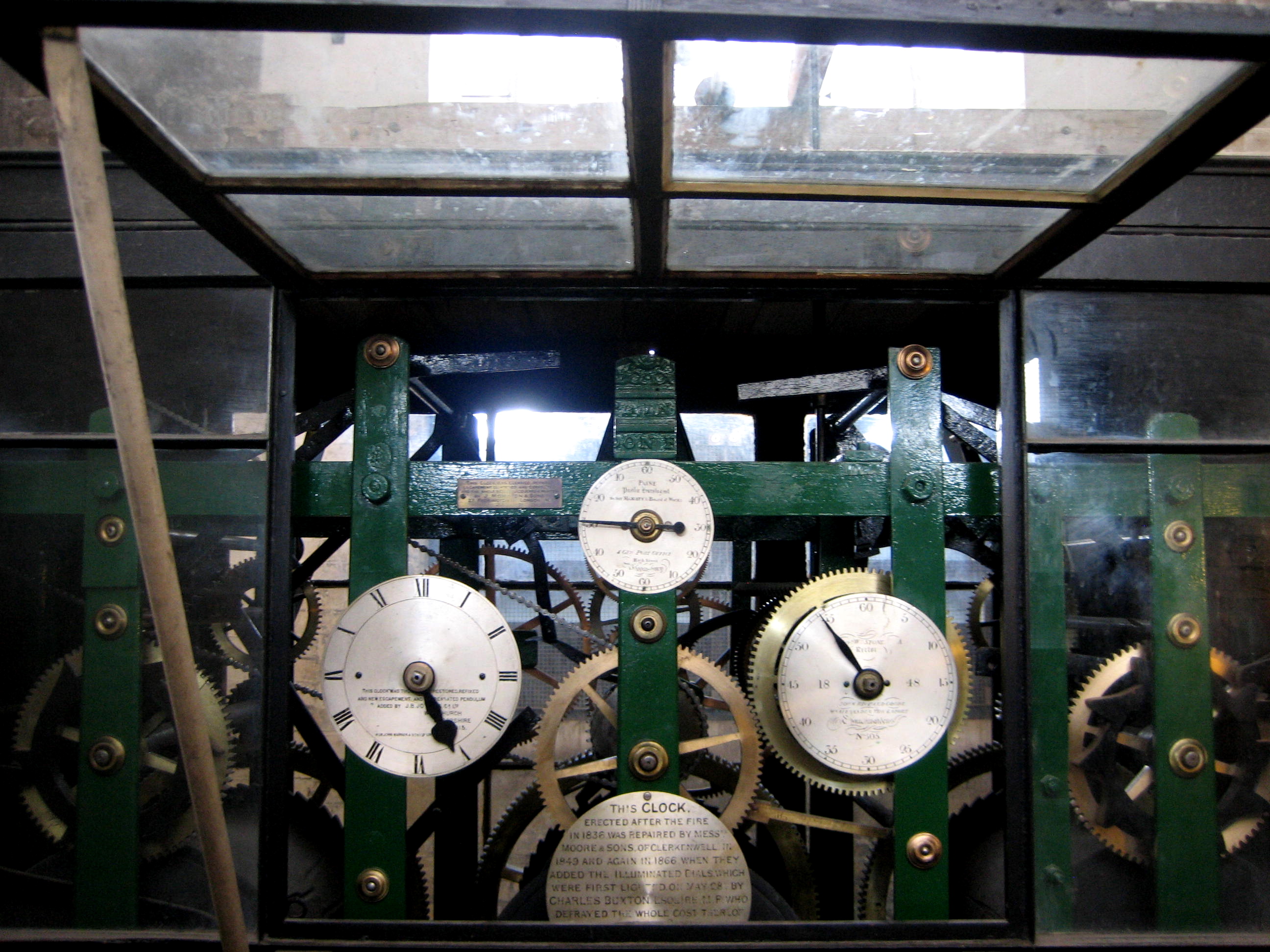

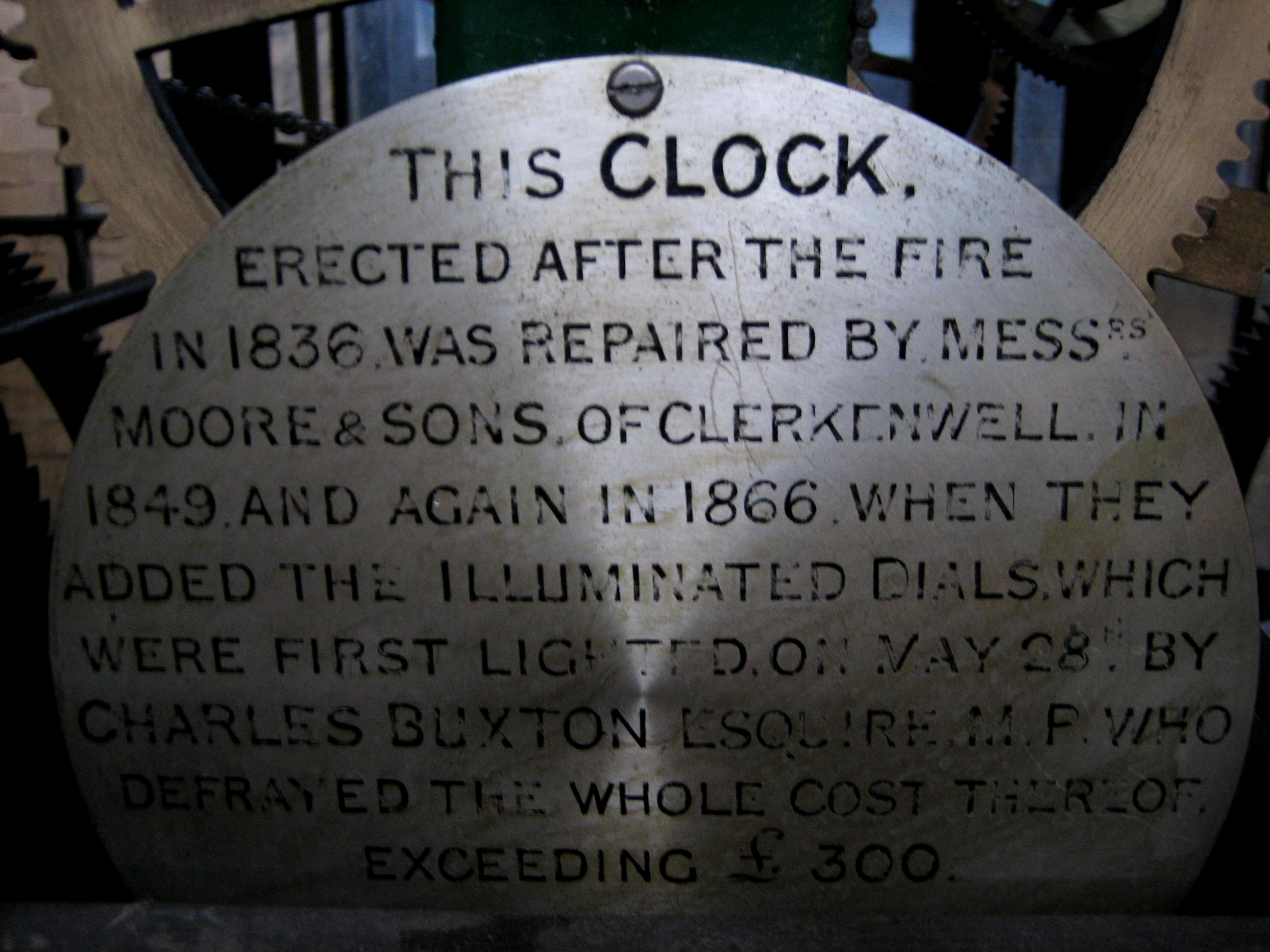

No-one has much cause to come up here and, when we reached the door at the top of the stairs, the verger was unsure of his keys. As I recovered my breath from the climb, while he tried each key in turn upon the ring until he was successful, I listened to the dignified tick coming from the other side of the door. When he opened the door, I discovered it was the sound of the lonely clock that has measured out time in Spitalfields since 1836 from the square room with an octagonal roof beneath the pinnacle of the spire. Lit only by diffuse daylight from the four clock faces, the renovations that have brightened up the rest of the church do not register here.

Once we were inside, the verger opened the glazed case containing the gleaming brass wheels of the mechanism, turning with inscrutable purpose within their green-painted steel cage, driving another mechanism in a box up above that rotates the axles, turning the hands upon each of the clock faces. Not a place for human occupation, it was a room dedicated to time and, as intervention is required only rarely here, we left the clock to run its course in splendid indifference.

By contrast, a walk along the ridge of the roof of Christ Church, Spitalfields, presented a chaotic and exhilarating symphony of sensations, buffered by gusts of wind beneath a fast-moving sky that delivered effects of light changing every moment. It was like walking in the sky. On the one hand, Fashion St and on the other Fournier St, where the roofs of the ighteenth century houses topped off with weavers’ lofts create an extravagant roofscape of old tiles and chimney pots at odd angles. Liberated by the experience, I waved across the chasm of the street to residents of Fournier St in their rooftop gardens opposite, just like waving to people from a train.

Returning to the body of the church, we explored a suite of hidden vestry rooms behind the altar, magnificently proportioned apartments to encourage lofty thoughts, with views into the well-kept rectory garden. From here, we descended into the crypt constructed of brick vaults to enter the cavernous spaces that until recent years were stacked with human remains. Today these are innocent, newly-renovated spaces without any tangible presence to recall the thousands who were laid to rest here until it was packed to capacity and closed for burial in 1812 by Rev William Stond MA, as confirmed by a finely lettered stone plaque.

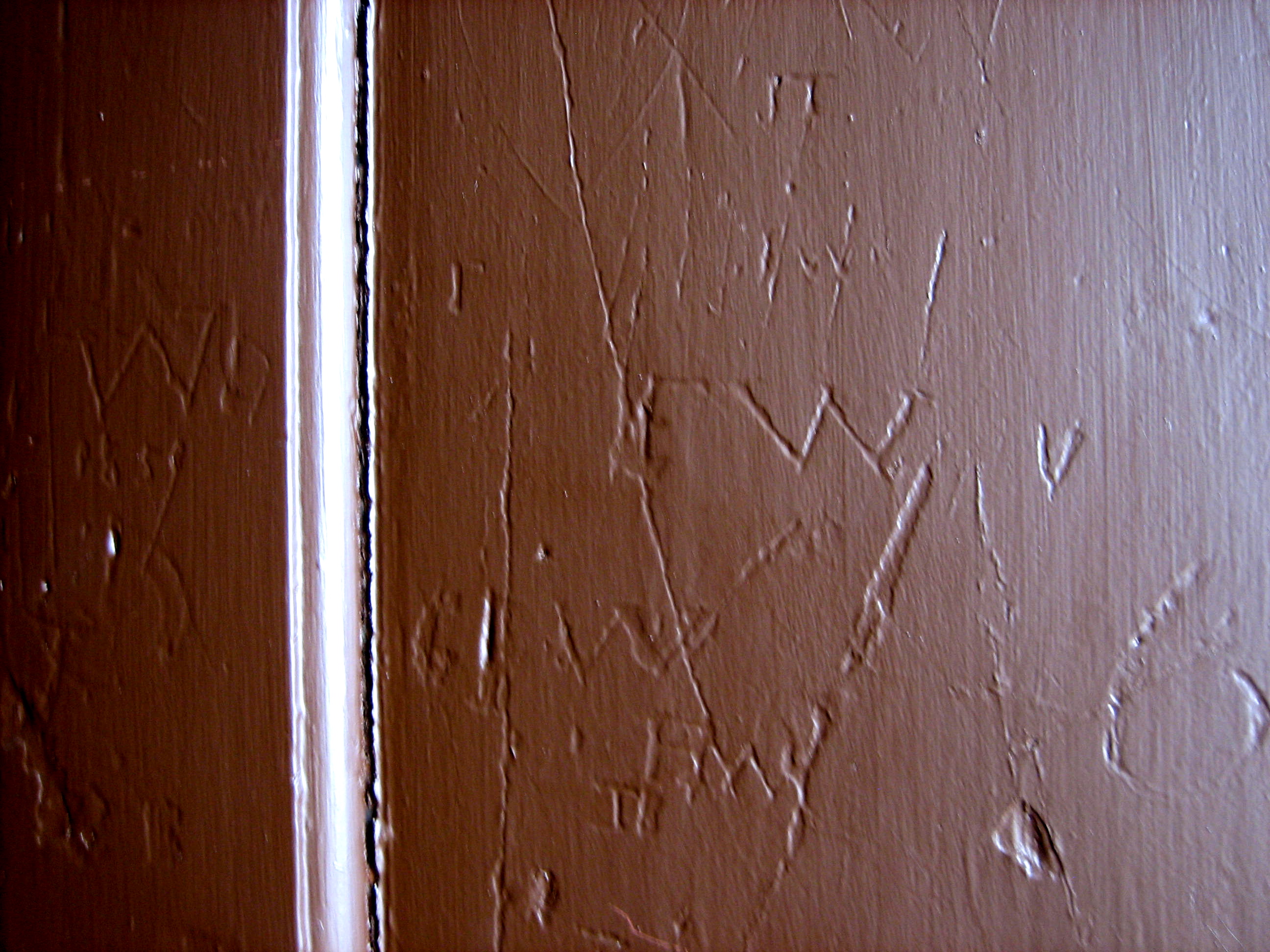

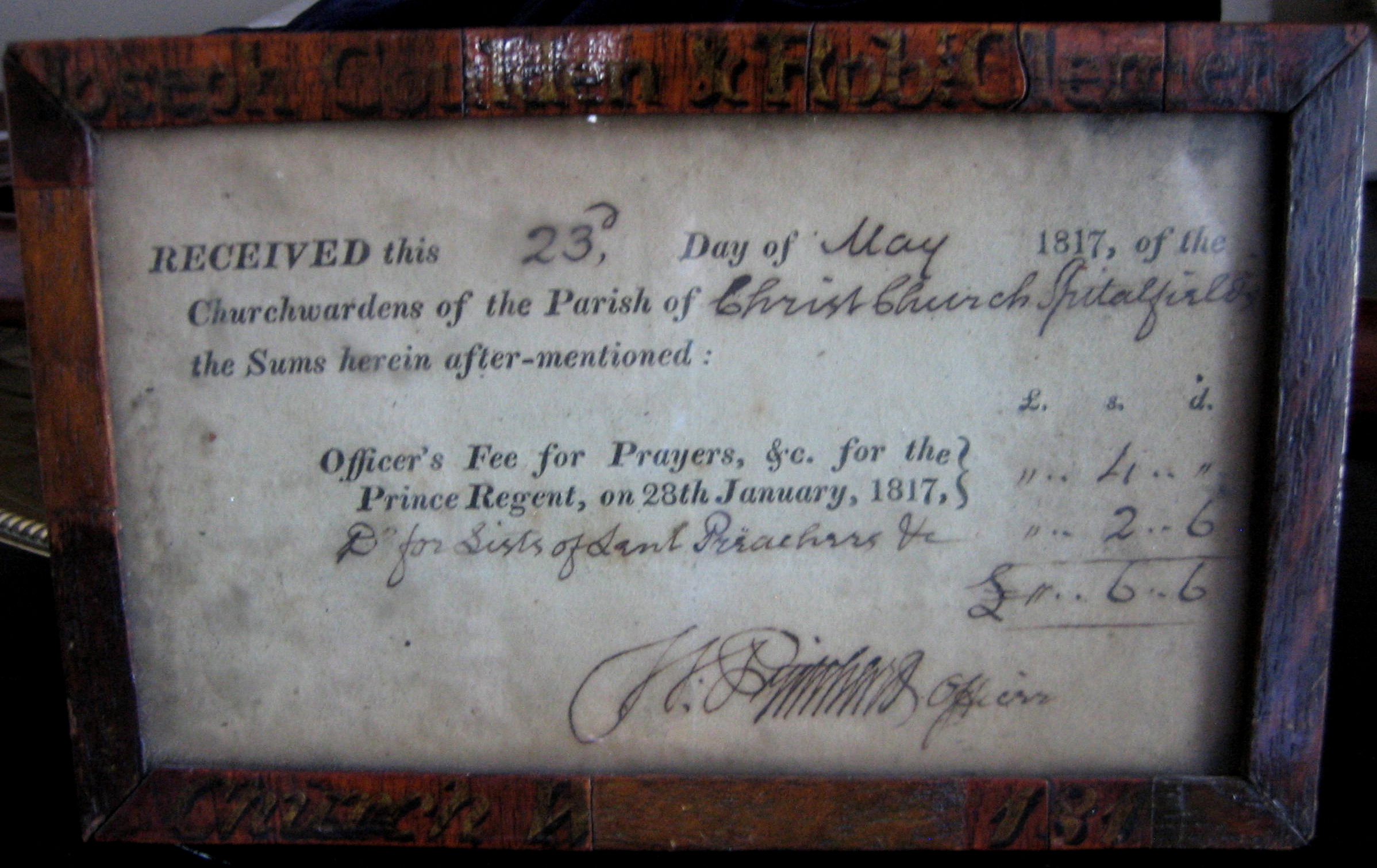

Passing through the building, up staircases, through passages and in each of the different spaces from top to bottom, there were so many of these plaques of different designs in wood and stone, recording those were buried here, those who were priests, vergers, benefactors, builders and those who rang the bells. In parallel with these demonstrative memorials, I noticed marks in hidden corners, modest handwritten initials, dates and scrawls, many too worn or indistinct to decipher. Everywhere I walked, so many people had been there before me, and the crypt and vaults were where they ended up.

My visit started at the top and I descended through the structure until I came, at the end of the afternoon, to the small private vaults constructed in two storeys beneath the porch, where my journey ended, as it did in a larger sense for the original occupants. These delicate brick vaults, barely three feet high and arranged in a crisscross design, were the private vaults of those who sought consolation in keeping the family together even after death. All cleaned out now, with modern cables and pipes running through, I crawled into the maze of tunnels and ran my hand upon the vault just above my head. This was the grave where no daylight or sunshine entered, and it was not a place to linger on a bright afternoon in May.

Christ Church gave me a journey through many emotions, and it fascinates me that this architecture can produce so many diverse spaces within one building and that these spaces can each reflect such varied aspects of the human experience, all within a classical structure that delights the senses through the harmonious unity of its form.

The mechanism of this clock runs so efficiently that it only has to be wound a couple of times each year

Looking up inside the spire

A model of the rectory in Fournier St

On the reverse of the door of the organ cupboard

In the vestry

For nearly three centuries, the shadow of the spire has travelled the length of Fournier St each afternoon

You may also like to read about

Those look like Witch/Apotropaic Marks on the back of the door?

Fascinating. Thank you GA

What a wonderful experience.When I visited a couple of years ago I noticed Brushfield St runs down from it.There are only two in the UK I live in the Nottingham one.One of Jack the Rippers victims was found there.It gave me a spooky feeling but Hawkswmoor is spooky.

Excellent stuff, the view along Fournier St from that angle remarkable. ?

Dear GA: Today’s article was a great read and beautifully written. Evocative too of parts of the church that are hard to access for most people. Thank you. The geometry of the view into the spire is terrific.

I don’t like high enclosed spaces with little steps up to them, so for me it’s a brave person who manages to get to the top of a spire. I never made it to the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa 4 years ago, got to the colonnade part where people walk round the outside, felt weird and let husband do the rest. Ashamed as it was my birthday treat!

Greetings from Boston,

GA, thank you for taking your readers on a tour of the hidden recesses of Christ Church. It is a stunning building that dominates most images that you provide of Spitalsfield. May it continue to be maintained and stand guard over the neighborhood for centuries to come.

What a privilege to explore so thoroughly such a special place, literally from top to bottom

>>his underground pornographic publishing empire

In fairness to Skilton, I think that’s a huge exaggeration. One of the (numerous) imprints he published was Luxor Press which published risque fiction titles such as “The School for Sin”. Whilst these book might well have been considered obscene in 1950s I think today they’d be considered pretty tame.

Hardly an “underground pornographic publishing empire” though.