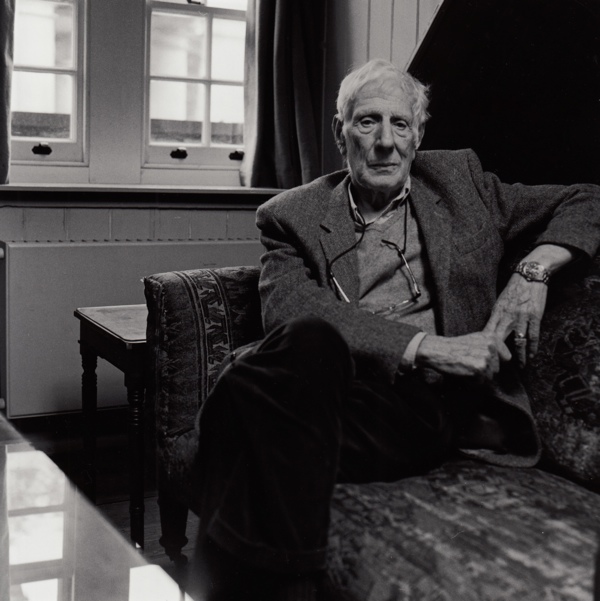

Jonathan Miller in Fournier St

Jonathan Miller, comedian, polymath and celebrated intellectual, visited 5 Fournier St last week, to see the house where his grandfather Abram lived and brought up his family more than a hundred years ago. Abram came to London from Lithuania in 1865 and worked as furrier in the attic workshop, the same room where Lucinda Douglas Menzies took this portrait of Jonathan.

Jonathan does not know when Abram acquired the surname Miller. His grandfather arrived in the Port of London as an adolescent and found work as a machinist in the sweatshops of Whitechapel, where he met Rebecca Fingelstein, a buttonhole hand, whom he married in 1871. Somehow Abram worked his way up to become his own boss during the next ten years, running his own business from premises at 5 Fournier St by the time his son (Jonathan’s father) Emanuel was born in 1892, as the youngest of nine siblings. Emanuel’s sister Clara remembered how the children fell asleep listening to the whirr of sewing machines overhead.

As a supplier of fur hats to Queen Victoria and bearskins to the Grenadiers, Abram aspired to be an English gentleman with a pony and trap. Yet, at 5 Fournier St, the horse had to be kept in the back yard which meant leading it through the front hall, blindfolded in case it reared up at the chandelier.

Jonathan’s aunt Janie wrote her own account of her childhood there – “We lived in a large Queen Anne House in Spitalfields and part of the house was taken over by my father’s business who was a furrier. Needless to say, we all had coats trimmed with fur… My earliest recollection was my first day at the infant school in Old Castle St, and I remember the summer holidays we spent in Ramsgate for two weeks, year after year.”

Janies’s younger brother Emanuel looms large in her narrative – “We moved to Hackney when he was eight and he went to Parminter’s School, and from there got a scholarship to the City of London School and then another scholarship to St John’s College, Cambridge. I remember spending a really lovely week in Cambridge for May Week, attending the concerts etc and meeting all Emanuel’s friends. After leaving Cambridge, he went to the London Hospital in Whitechapel where he qualified as a doctor and served in the 1914 war as a Captain RAMC, and helped to cure the shell-shocked soldiers.” It was a long journey that Emanuel travelled from his father’s beginnings in Whitechapel and, as Janie records, he rejected the family trade in favour of the medical profession, “Emanuel refused to go into the business, as he had been to Cambridge and wanted to be a doctor, and he won the day.”

Jonathan Miller does not recall Emanuel speaking about the East End. “I never talked to my father very much because I was always in bed by the time he was back from his work, so I was completely out of it” he admitted to me, “I am only a Jew for anti-Semites. I say ‘I am not a Jew, I’m Jew-ish!'”

Although intrigued to visit the house where his father was born and where his grandfather worked, Jonathan was unwilling to acknowledge any personal response. “I’m not interested in my ancestry,” he joked, “I’m descended from chimpanzees but I am not interested in them either.” Like many immigrant families that passed through Spitalfields, in Jonathan’s family there was a severance – the generation that moved out and rose to the professional classes chose not to look back. And for Jonathan it was a gap – in culture and in time – that could no longer be bridged, even as we sat in the attic where his grandfather’s workshop had been a century earlier. “I know nothing about their life here,” he confessed to me, gesturing extravagantly around the tiny room and wrinkling that famously-furrowed brow.

As one who has constructed his own identity, Jonathan rejects distinctions of religion and ethnicity in favour of a broader notion of humanity to which he allies himself. Yet he was proud to tell me that his father came back and founded the East London Child Guidance Clinic in 1927, acknowledging where he had come from by bringing his scholarship to serve the people that he had grown up among. “He was interested in juvenile dilinquents and he was really the founder of child psychiatry in this country,” Jonathan explained me, and the work that his father began continues to this day – with the Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services on the Isle of Dogs housed in the Emanuel Miller Centre.

So I found a curious irony in the fact that the son of a leading figure in the understanding of child development in this country should admit to no relationship to his father, and therefore none to his family’s past either. When 5 Fournier St was renovated, the gaps between the floor boards were found to be crammed with clippings of fur and every inch of this old house bears the marks of its three hundred years of use. Constantly, people come back to Spitalfields to search for their own past in the locations familiar to their antecedents, yet often the past they seek is already within them in their cultural inheritance and family traits – if they could only recognise it.

Clearly, Jonathan Miller’s choice to study medicine was not unconnected to his father’s career. When Jonathan reminded me of the familar Jewish joke about asking the way to get to Carnegie Hall and receiving the reply, ‘Practice, practice!’, he suggested that the pursuit of fame as musicians and as comedians had proved to be an important means of advancement for Jewish people. And I could not but think of Jonathan Miller’s own distinguished work in opera and his early success with ‘Beyond the Fringe.’ It set me wondering whether ancestry had influenced him more than he realised, or was entirely willing to admit.

Eighteenth century roof joists, exposed during renovations, still with their original joiner’s numbers which reveal that the roof was made elsewhere and then assembled on site.

Weatherboarding revealed between 3 and 5 Fournier St during renovations, indicating that until the mid-eighteenth century number 5 was the end of the street, before number 3 was built.

Abram Miller arrived from Lithuania in 1865 and is recorded at 5 Fournier St in the census of 1890 .

Wallpaper at 5 Fournier St from the era of Abram Miller.

Watercolour of Fournier St, 1912 – the cart stands outside number 5.

Emanuel Miller was born at 5 Fournier St in 1892.

“I remember the summer holidays we spent in Ramsgate for two weeks year after year.” Emanuel is on the far right of this photograph.

Fournier St in the early twentieth century, number 5 is the third house.

5 Fournier St today, now the premises of the Townhouse.

The hallway where the blindfolded horse was led through.

Emanuel Miller as an old man.

Jonathan Miller

Portraits of Jonathan Miller © Lucinda Douglas Menzies

Sad indeed that the grandson seems to reject his family heritage. I cannot understand why he came to see the house in Fournier Street.

Karkur Israel

What wonderful Jewish faces! The nose, the dark eyes, those spectacles worn by many. Emanuel Miller’s photo is just beautiful.

It seems quite disappointing to me, that a person doesn’t easily recognise the great work of less-educated forebears and be very proud of such hard work. I’m sure Abram was easily as clever as those who came down the generations from him. His achievements need to recognised and applauded by all his family. Too many families operate this way once some become Professionals.

It brings to mind the superb writing of Chaim Potok, the late Jewish rabbi. “My Name of Asher Lev” was one read which brought, to me, a clearer understanding of some Jewish thinking.

Top story of successful hardworking migrants, gentle author.

Conversation(s) with my father during my formative years never happened; many rows and the occasional whack- yes but not conversation. An interesting, but IMO not an uncommon account of C19th Jewish immigration.

I think Jonathan Miller is being slightly disingenuous. If he was that uninterested in his ancestry I don’t think he would have made the journey to Fournier Street. Whatever his reasons he has an ancestry to be proud of.

beyond the fringe came just before the beatles and swinging london. i remember thinking how exciting it was. i am sorry to think that jonathan miller, ignoring schiller, has forgotten the dreams of his youth. it was about feisty striving london. or my youth was, anyway.

http://www.quotationspage.com/quote/3051.html

I agree with Peter Holford’s comment.I can also add Miller is a marvellous person.I had the honour to work with him in Zürich on an opera production.One could sit and talk to him for hours -absolutely fascinating man.

A fantastic post, made me a little sad though.

I understand his position, I’m interested to some degree in my ancestry but it matters not a jot to who I am today.

I quite understand Jonathan Miller’s disinterest. Family history can be deeply dull to the outsider and rather depressing for the person looking back. Miller is much more concerned with the urgent and exciting possibilities of the here-and-now. I recall his boyish enthusiasm in an excellent TV documentary, rummaging around a scrap-yard searching for bits of metal for his sculptures….

Where and who would Jonathan Miller be today if it wasn’t for his grandfather’s hard work and obvious courage in coming to England in the first place? I’m afraid the word ‘snob’ was my first thought on reading this article. To show no interest in his ancestry is an insult to Abram.

Very insteresting post … I wouln’t imagine there was such history behind these walls …

Thank you for writing this post. Abraham was my great great grandfather. I have been researching him and all the family history for years now and I love to find out anything I can about him. I have never met Jonathan Miller but I know of him through my Father. I have met his sister Sarah Miller rip, who was a fantastic genealogist and had a great love of her family roots as do I.

I have just visited 5 Fournier Street, Spitalfields, London on Saturday 19th July. I am the great grand-daughter of Abram Miller, and posted a message on the board inside the antique shop. I am very interested in the family history on my father’s side (David Levy).

Hello Gentle Author,

I recall seeing a film of Jonathon Miller in the houseon Fournier Street. Do you know what television programme this was from as I cannot locate it anywhere now?

Thank you