Bill the Ostler of Spread Eagle Yard

Last week, I wrote about Pearl Binder, the artist and writer, who lived in the seemingly idyllic Spread Eagle Yard in Aldgate during the nineteen twenties and thirties while studying at the Central School of Art. Binder was a life-long socialist, whose political beliefs were informed by her formative experiences in the East End.

This week, I am publishing these excerpts from her pen portrait of Bill the Ostler, who with his wife Emmie, was Pearl Binder’s neighbour in Spread Eagle Yard. It was originally included in her book “Odd Jobs”” published in 1935. This is a plain story, revealing the effects of the shift from horsepower to the petrol engine upon the life of a modest couple with little control over their destinies. A tale of the shifting labour market as a consequence of industrial and technological change, that became all too familiar as the century wore on, but no less devastating for those at the mercy of these changes.

Pearl Binder’s self-effacing protagonists, like Arnold Bennett’s dignified characters, draw us to empathise with feelings that are all the more poignant for being understated or withheld.

Bill began work as a butter-slapper in the local branch of the Home and Colonial. Later he drifted into driving vans for one of the City straw merchants. After twenty-five years of van-driving, his feet had become so crippled that the Governor gave him the job of Ostler instead.

As Ostler, Bill, together with his wife Emmie, was sent to live in the horse-keeper’s cottage in the Governor’s straw yard. He applied himself to his new job with patient industry, spreading his affection for his own horse over twelve. His duties consisted in feeding and grooming the twelve cart-horses, cleaning the stables after the last load of hay had been weighed and stacked in the hay-loft and acting as a caretaker when the office was closed. He received a small wage and lived rent-free.

The proud heraldic eagle, which gave the Yard its name, spread its stone wings above the big clock in the north wall of the Yard. Over a hundred years ago, the clock had stopped at twenty-five minutes past nine. The Yard had once been the inn yard of the old Spread Eagle Inn.

The sweet smell of the hay in the lofts and the peaceful cooing of the pigeons in the Yard seemed so remote from the cosmopolitan roaring of the City, just outside the gate, that Emmie used to imagine herself in the country. In the cool of the evening, Bill would take his stumpy pipe and sit outside the Yard, in the door-way of the big gate, watching the swirling life of the city go by and resting his aching feet after his day’s work.

He never tired of the endless procession: modish little Jewesses from Whitechapel escorted by bold-eyed sweethearts with bravely padded shoulders, noisy children from Leman Street, their smooth Egyptian heads sticking precociously above English gymnasium tunics and cheap Norfolk suits, sad-eyed Malay sailors on their way to the East India Dock Rd, swarthy turbaned Lascars carrying brand-new cardboard suit-cases, argumentative Irish labourers on their way to Shadwell public houses, silent Chinese from Pennyfields, hurried businessmen from the City, and the rector from St Mary’s.

Early in June, the governor’s clerk informed Bill that the business was closing down and that the Yard was going to be let. The increasing motor traffic was making the sale of hay unprofitable.

The sun shone dazzlingly in the Yard on the day of the auction, and the heavy air, pungent with hay barely stirred. Bill had risen especially early to sweep and sand the Yard. Lovingly he groomed the horses to immaculate satin, and in their fine tails he plaited braids of straw.

The sale began. One by one, Bill led out the gleaming cart-horses for inspection, each with a numbered paper disc newly stuck on its flank. When all the horses had been sold, the carts were quickly knocked down. After that the bales of hay were disposed of in an off-hand manner, as though of little significance.

The Governor said that they could go on living in the cottage, for the time being at least. The Yard itself was not yet sold. In the meantime, they could remain there and keep an eye on the place. But no wages. He advised Bill to apply for the dole. When the dreadful day came to sign on at the Labour Exchange, he was so ashamed and nervous that he could hardly hold the pen in his hand to write.

Emmie tried to be cheerful. She vowed that Bill would soon be in work again. His character and his copperplate handwriting were in his favour. But he was getting on for sixty and his feet were against him. She tried to persuade him to take a walk every day, for the good of his health, across Tower Bridge towards Bermondsey, or in the other direction as far as the Whitechapel Library, where the workless men crowded outside the entrance round the Want ads, displayed under a wire frame.

November saw the hasty installation of a fun fair. The Yard buildings suffered the indignity of orange-coloured paint. The proud stone creature above the silent clock was daubed with aluminium. Ringed round with electric globes, the clock itself stared down from this disguise, its hands fixed immovably at nine-twenty-five. The cottage was festooned with coloured electric lights, and even Emmie’s sandstoned front step, hollowed out by two hundred years of footsteps, was smeared over with silver paint. The whole Yard looked startled and outraged like a dignified old lady forcibly tricked into wearing flashy modern clothes.

The fun fair opened at last. The twentieth century swarmed in from the street and ran riot over the eighteenth. Outside the gate glittered LUNAPARK in red and white electric bulbs, and inside the Yard blazed with coloured points of light, containing here and there a sudden blank where the hasty work had fused. The alley entrance to the Yard was decorated with a row of wildly distorting mirrors, which proved such a big attraction that the gangway was constantly blocked. Bill did not like the invasion. His dignity and his quiet were gone. There was no more smell of horses in the Yard.

The new boss promised to give Bill some sort of job when the fair started. The white faced boy asked Emmie if she could provide him with a bite of dinner each day. He could afford sixpence. Emmie contrived to cook up a daily plateful of meat and vegetables, which the boy fell upon ravenously. In between mouthfuls, he informed her that his father had been dead some years and that he, being the eldest of six children, was the mainstay of his mother. He said he had been at work four years already and was seventeen.

The scattered morsels of food presently attracted swarms of hungry rats, and the boss, cursing at the expense, ordered Bill to put rat poison in all the corners. Bill’s new job was to sweep up the Yard every night when the fair ended and to act as caretaker at all times. Wages one pound a week, less insurance, and the cottage rent free again. Little as it was, he and Emmie were both deeply relieved. It was less than the dole, but more respectable.

With the loss of his job as an Ostler, separated from his intimate working relationship with horses, Bill became an anachronism of an ancient world, and, in retrospect, the Lunapark funfair reads as both emblematic and prophetic of the modern world. His story is a fable that stands for a million other personal tragedies of dislocation that continue around us today, whenever the lives of small people are sacrificed to big changes beyond their control.

All this Pearl Binder witnessed in the place she first took lodgings when she came to the London as a young woman, the fate of Spread Eagle Yard – the hay yard that became a theme park – was a microcosm of the twentieth century itself.

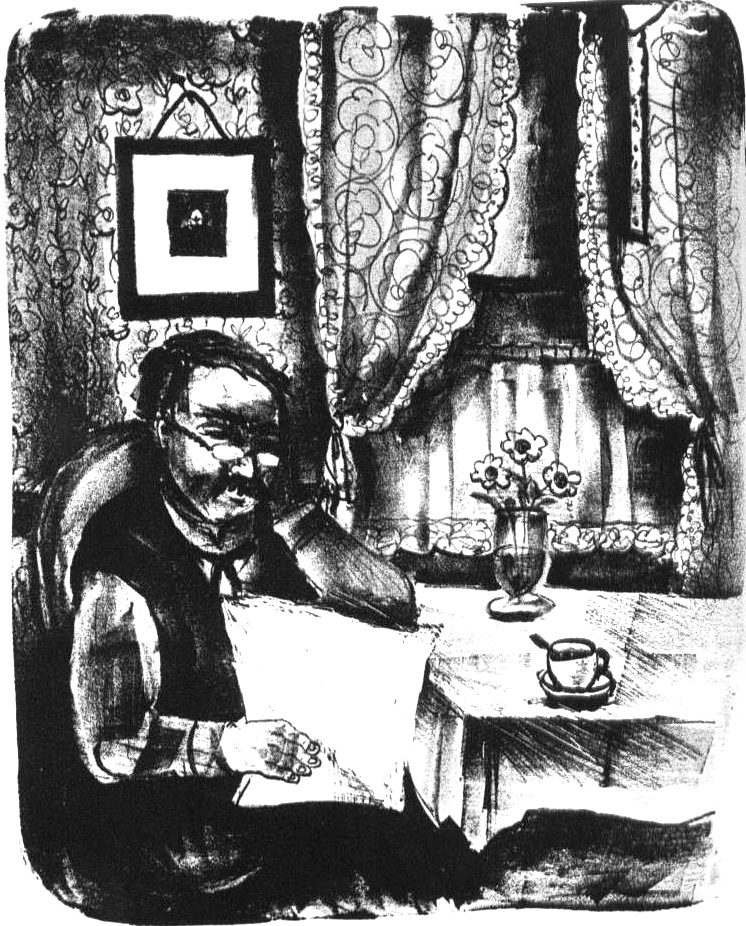

Bill the Ostler

What a sad, sweet story. Bill would normally be only a statistic — jobs lost in transition to the modern world — if not for you and Pearl Binder. Now I can see him brushing the coats of the horses until they shown like satin one last time.

Interesting blog. I possess the book “The Real East End” by Thomas Burke and Pearl Binder, which contains the first two of the above illustrations. First published 1932, it contains many more amazing illustrations by this lady. The book itself contains many more East End stories, including from Spread Eagle Yard.