At Oitij-jo Kitchen

‘We want to celebrate the work that the women do’

People often ask where they can find authentic Bengali food in Spitalfields and I have found the answer in Oitij-jo Kitchen, a women’s collective who run the catering operation at Rich Mix Arts Centre in the Bethnal Green Rd. This Sunday April 14th you can join the Eid celebrations there and experience a traditional Bhorta Bengali New Year lunch, served from 1pm – no booking required.

Last week, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie spent a morning recording the activity in the kitchen while I sat down with co-founder Maher Anjum who explained to me what it is all about, before we all reconvened for a taste test.

“Four of us set up the Oitij-jo collective in 2013 straight after the 2012 London Olympics. We had Akram Khan in the opening ceremony but nothing else. We were all creatives, so we asked ourselves ‘Where are we in this scenario?’

We set up Oitij-jo to be a platform for creative practitioners from the Bangladeshi disapora, representing them, supporting them, especially emerging artists, but also showcasing our rich cultural heritage and translating it into what is happening now. Oitij-jo in bangla means heritage. It was important to us to take it to the future, so that the next generation have an understanding and can interpret it in their own way, because it is only at that point that it is alive.

In 2016, we did a year’s residency at the Gram Bangla restaurant in Brick Lane displaying art works with a new exhibition every three months. It was the first restaurant which served traditional Bengali food, and that was when food became part of our project. We had a lot of conversations with the restauranteurs about the nature of our food. And we realised that food was such an important part our cultural identity, it was something we wanted to work with. There was a visible lack of women in the restaurant sector and in catering in general, so we decided to focus on bringing in Bangladeshi women. It’s culture that people carry, even if may not pay attention to it, we simply say ‘Have some food.’

One of the things that women who work with us tell us is, ‘People say ‘thank you’ for the food I prepare for them. That’s really nice because at home it’s taken for granted. No-one’s going to thank you for the food you put on the table, it’s come-eat-go.’ For a lot of these women, the recognition of what they are doing is a recognition of themselves and food becomes an intrinsic part of who they are, part of their identity.

British Bangladeshi women are some of the least economically active of the population this country, three times less likely to be paid the same wages as anyone else. What are we doing about it? The creative sector is one of the most productive, but the involvement of black, Asian and people from other ethnic minorities is one of the least.

We see Otijo-jo kitchen as the means of giving women the pathway to self-discovery and self-esteem, while exploring the question of what is food for the British Bangladeshi community.

The so-called colonial curry – and what is seen to be ‘curry’ – has a complicated lineage, but there is a place for it and it has made a huge contribution to the community where employment was not available. It was a way for people to establish themselves and be their own bosses, rather than waiting for a job that might never come. We need to acknowledge that but it gets complicated when we ask, ‘What is the food? Who does it? And how does it happen?’

What we want to do is something quite different. We want to celebrate the work that the women do and the food which we consider is traditional Bengali food that people eat at home.

We could not get any funding, so we did a crowdfund in 2018 and raised a tiny amount of money, and started in 2019. Since then we have worked with about sixty women. We do not expect them to stay with us because we want them to gain the ability and self-confidence, get the skills and experience, and move on to do what they want to do.

Many women who come to us have never been in paid employment, they have very little experience of being outside the home or being in a working environment. We want them to build up the confidence to say ‘I can be here’ and be able to talk to people.

We have around a dozen women working with us at present. Once the women have finished their training period, they can stay on working with us and earn the London Living Wage. While they are training with us, they get a daily bursary.

We are a charity and a social enterprise, so we have to make sure we earn money to continue this work. Over the years, we have developed menus and recipes that are our style of cooking. The women who join us learn to cook our recipes the way we cook them.

We serve food at Rich Mix each Thursday to Sunday from 3pm to 9pm. The rest of the time, we use the kitchen here to do catering. We do conferences, seminars, weddings, any kind of occasion. We provide a hundred student lunches for a university twice a week, that’s a very different kind of catering. We did a conference for the Serpentine Gallery at Somerset House for one hundred and twenty people, breakfast, tea, lunch and something in the afternoon too.

Most of the women find us through word of mouth and we are having people contacting us all the time. We have a wide range of ages from around twenty to over sixty and we feel that’s really important because they brings different skills, experiences and abilities. Women come from across Tower Hamlets and the East End.

When we first started, someone asked, ‘If people want vegan food, what shall we give?’ If you have plain rice and dhal which is a standard Bengali meal, that is vegan. Bangladesh is a nation of rivers, so our heritage is that we eat vegetarian and vegan food all the time. You could say that we are going with the trend, except that is normal traditional food for us.”

Surma Khanom, Maher Anjum, Hajira Bibi & Rohema Begum

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Blossom Time In The East End

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

In Bethnal Green

Let me admit, this is my favourite moment in the year – when the new leaves are opening fresh and green, and the streets are full of trees in flower. Several times, in recent days, I have been halted in my tracks by the shimmering intensity of the blossom. And so, I decided to enact my own version of the eighth-century Japanese custom of hanami or flower viewing, setting out on a pilgrimage through the East End with my camera to record the wonders of this fleeting season that marks the end of winter incontrovertibly.

In his last interview, Dennis Potter famously eulogised the glory of cherry blossom as an incarnation of the overwhelming vividness of human experience. “The nowness of everything is absolutely wondrous … The fact is, if you see the present tense, boy do you see it! And boy can you celebrate it.” he said and, standing in front of these trees, I succumbed to the same rapture at the excess of nature.

In the post-war period, cherry trees became a fashionable option for town planners and it seemed that the brightness of pink increased over the years as more colourful varieties were propagated. “Look at it, it’s so beautiful, just like at an advert,” I overheard someone say yesterday, in admiration of a tree in blossom, and I could not resist the thought that it would be an advertisement for sanitary products, since the colour of the tree in question was the exact familiar tone of pink toilet paper.

Yet I do not want my blossom muted, I want it bright and heavy and shining and full. I love to be awestruck by the incomprehensible detail of a million flower petals, each one a marvel of freshly-opened perfection and glowing in a technicolour hue.

In Whitechapel

In Spitalfields

In Weavers’ Fields

In Haggerston

In Weavers’ Fields

In Bethnal Green

In Pott St

Outside Bethnal Green Library

In Spitalfields

In Bethnal Green Gardens

In Museum Gardens

In Museum Gardens

In Paradise Gardens

In Old Bethnal Green Rd

In Pollard Row

In Nelson Gardens

In Canrobert St

In the Hackney Rd

In Haggerston Park

In Shipton St

In Bethnal Green Gardens

In Haggerston

At Spitalfields City Farm

In Columbia Rd

In London Fields

Once upon a time …. Syd’s Coffee Stall, Calvert Avenue

Neil Martinson, Photographer

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

Neil Martinson documented the working life of Hackney and the East End throughout the seventies and eighties. Neil was born and brought up in Hackney, where he started taking street scenes and became a founder member of the Hackney Flashers photography collective.

Cheshire St

Steve Manning

Ridley Rd Market

Brian Simons

Bethnal Green Rd

Tony Kyriakides

Ken Jacobs

Ken Jacobs

Brian Simons

Stoke Newington

Ridley Rd Market

Lew Lessen

Abney Park Cemetery

Photographs copyright © Neil Martinson

You may also like to take a look at

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries Of London

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

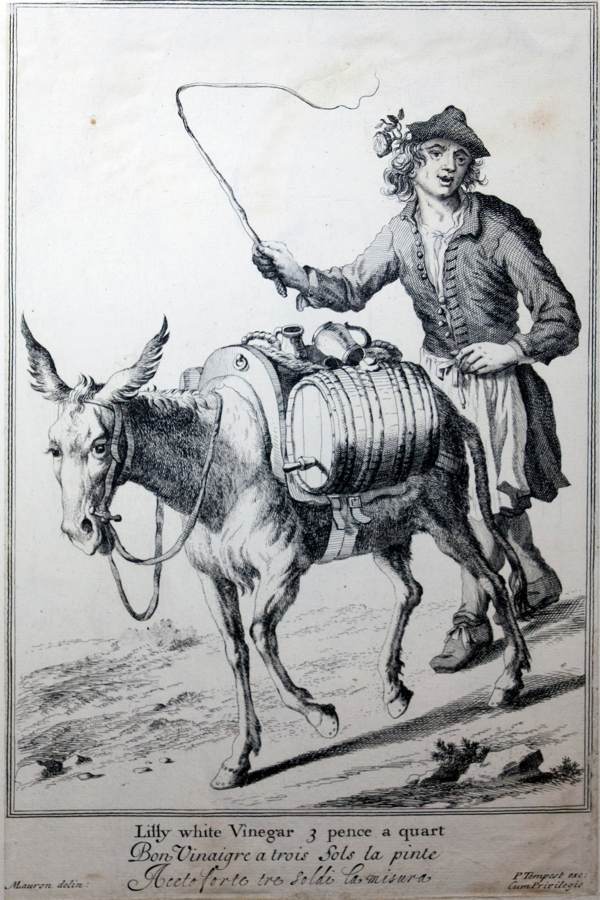

Today it is my pleasure to publish Marcellus Laroon’s vibrant series of engravings of the Cries of London reproduced from an original edition of 1687 in the collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

The death of Oliver Cromwell and the restoration of Charles II made the thoroughfares of London festive places once again, renewing the street life of the metropolis. After the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed the shops and wiped out most of the markets, an unprecedented horde of hawkers flocked to the City from across the country to supply the needs of Londoners .

Samuel Pepys and Daniel Defoe both owned copies of Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London. Among the very first Cries to be credited to an individual artist, Laroon’s “Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life” were on a larger scale than had been attempted before, which allowed for more sophisticated use of composition and greater detail in costume. For the first time, hawkers were portrayed as individuals not merely representative stereotypes, each with a distinctive personality revealed through their movement, their attitudes, their postures, their gestures, their clothing and the special things they sold. Marcellus Laroon’s Cries possessed more life than any that had gone before, reflecting the dynamic renaissance of the City at the end of the seventeenth century.

Previous Cries had been published with figures arranged in a grid upon a single page, but Laroon gave each subject their own page, thereby elevating the status of the prints as worthy of seperate frames. And such was their success among the bibliophiles of London, that Laroon’s original set of forty designs – reproduced here – commissioned by the entrepreneurial bookseller Pierce Tempest in 1687 was quickly expanded to seventy-four and continued to be reprinted from the same plates until 1821. Living in Covent Garden from 1675, Laroon sketched his likenesses from life, drawing those he had come to know through his twelve years of residence there, and Pepys annotated eighteen of his copies of the prints with the names of those personalities of seventeenth century London street life that he recognised.

Laroon was a Dutchman employed as a costume painter in the London portrait studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller – “an exact Drafts-man, but he was chiefly famous for Drapery, wherein he exceeded most of his contemporaries,” according to Bainbrigge Buckeridge, England’s first art historian. Yet Laroon’s Cries of London, demonstrate a lively variety of pose and vigorous spontaneity of composition that is in sharp contrast to the highly formalised portraits upon which he was employed.

There is an appealing egalitarianism to Laroon’s work in which each individual is permitted their own space and dignity. With an unsentimental balance of stylisation and realism, all the figures are presented with grace and poise, even if they are wretched. Laroon’s designs were ink drawings produced under commission to the bookseller and consequently he achieved little personal reward or success from the exploitation of his creations, earning his living by painting the drapery for those more famous than he and then dying of consumption in Richmond at the age of forty-nine. But through widening the range of subjects of the Cries to include all social classes and well as preachers, beggars and performers, Marcellus Laroon left us us an exuberant and sympathetic vision of the range and multiplicity of human life that comprised the populace of London in his day.

Images photographed by Alex Pink & reproduced courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Peruse these other sets of the Cries of London I have collected

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

CLICK TO BUY A SIGNED COPY OF CRIES OF LONDON FOR £20

Maurice Sills, Cathedral Treasure

Click to book for my next tour of the City of London on Sunday April 21st

Maurice Sills – ‘I learnt to live – I think – a full life’

If you were to read the staff list at St Paul’s Cathedral, where Maurice Sills was described simply as ‘Cathedral Treasure’, you might assume that a final ‘r’ had been missed from the second word. But you would be wrong, because Maurice Sills was in the world longer than you or I have been in the world – longer, I venture, than anyone reading this article. The truth is that Maurice Sills lived to be nearly one hundred and two years old, and he genuinely was a ‘Cathedral Treasure’ at St Paul’s.

Travelling to work by rail and tube from his home in North London three times a week, Maurice regularly gave up his seat to what he termed ‘old ladies,’ by which he meant women of a generation later. There was an infectious enthusiastic energy about Maurice which he kept alive through a long term involvement with sport and his delight in the presence of young people.

We met in the Chapter House at St Paul’s but Maurice was keen to take me up to the magnificent library, embellished with luxuriant carving by Grinling Gibbons, high in the roof of the old cathedral. When completed, the shelves were empty since all the books had been destroyed in the fire, but now the library is crowded with ancient tomes and Maurice catalogued every one.

In this charismatic shadowy place, Maurice was completely at home – as if the weight of all his years fell away, rendered inconsequential by comparison with the treasures of far greater age that surrounded us, sequestered in an ancient library where time stood still.

Maurice – My earliest memory of anything – it must’ve been 1918 – was when I was staying with a relation who was manager of a grocer’s shop called Palmer’s in Mare St, Hackney, while my mother was having another child. They sold provisions – on one side you had bacon, butter and so forth and the other side fruit and vegetables. I can still picture us going down the wooden stairs of the shop into the cellar and, in the cellar, there was an oil stove, one of these with little holes in the top that cast lights onto the ceiling – I can still see those lights there. I worked out from my relations who I stayed with that it was a Zeppelin raid! So that was my first memory of life – those little marks on the ceiling while I was down in the cellar.

The Gentle Author – Maurice, are you a Londoner?

Maurice – Certainly I’m a Londoner, if West Norwood is London, yes. I was born there in 1915 and my baby brother still lives in the same house where he and I and five brothers were born, six of us all together.

The Gentle Author – What were your parents?

Maurice – My father worked in the Co-operative Bank. My mother was purely a mother, with six boys she had no choice but to be a mother! Norwood, in those days, was almost a village. My mother’s family were the local undertakers and everybody knew them. When somebody else opened up another undertakers that caused trouble. My parents got married a few months after my mother’s father died. My mother had to look after him when he was a widower, so she couldn’t get married. That’s how families were in those days, but when her father died that was freedom, so she had a quiet wedding and we were brought up in the house.

The Gentle Author – And what kind of childhood did you have?

Maurice – Being the eldest of six I had a lot of freedom because my mother had enough to do looking after the others – the three youngest boys were triplets. So I learnt to enjoy life. I was encouraged to enjoy sport by my father who played cricket and I became scorer for his team when I was eight. Cousins made sure I knew what soccer was like, so I enjoyed soccer for the whole of my days until lately. I played for my old school boys until I was forty-nine when I then got hurt badly and had to give up. My mother said, ‘Serve you right, you should’ve given up before,’ but I still played cricket until I was demoted to be the umpire because they wanted younger people, they said.

The Gentle Author – How old were you then?

Maurice – About eighty. They often asked me, as an umpire, where my dog was? Well, a blind man has a dog!

The Gentle Author – Did your parents bring you up to London to the West End?

Maurice – No, because we didn’t go far. We had a fortnight’s holiday every year in Bognor, Eastbourne or Clacton – a long way then. Other than that, the only outings I took on my own would be on bank holidays when I went to Crystal Palace where there was always a lot to see, whether it was motorcycle racing, speedway racing, or concerts.

When I was eleven, I obtained a free place at St Clement Dane’s school close to Bush House in the Aldwych, so I used to travel from South London on a tram every day to the Embankment and walk up the road to school.

The Gentle Author – What were your impressions of the city then?

Maurice – One was of The Lord Mayor’s show, which was not always on a Saturday as it is today. We were allowed to go into the churchyard at St Clement Danes and see the procession go by. The other thing which stuck in my mind was that every Christmas, Gamages in Holborn used to have a cricket week where well-known cricketers came, so I would go to obtain their autographs. But other than that, in a quiet way, I suppose I got to know London very well. I had a season ticket to town so, after two or three years, I would go to museums on my own. I was allowed complete freedom.

The Gentle Author – How wonderful for you to explore London.

Maurice – It meant I learnt a lot about it. I went to evening classes at Bolt Court just off Fleet Street. There were lectures on the City of London and summer evenings would be spent walking round to see things we had heard about.

The Gentle Author – Were you a good student?

Maurice – I did all the essays I was asked to do. I kept them til a few months ago when I was moving into an old people’s home and I decided I’d just got to say goodbye to them. I’ve no regrets. It was all wastepaper, it had been in a drawer for twenty years.

The Gentle Author – What age did you leave school?

Maurice – Seventeen. At that time it was very difficult to get a job.

The Gentle Author – This is the Depression?

Maurice – 1932. Like in the world today, it’s not who you are but who you know, and my father knew somebody so I started working. I went for interviews in banks, but I couldn’t pass the medical test. They weren’t very sure about my heart so they wouldn’t take me on. My father knew somebody at Croydon, not too far from where we lived, at the Co-operative there, so I worked at the office from 1932 to 1940, doing clerical work, and playing football and cricket, until the war came and I then went into the Navy for five years.

The Gentle Author – How did your involvement with St Paul’s Cathedral come about?

Maurice – In 1978, when I was at evening class at Bolt Court, a lady said to me at the tea break,‘You’ve just retired, you could come and help at St Paul’s.’ I came for a few months every Thursday and one day I took a school party round. Evidently, they wrote and said they had an interesting time, because the Dean asked me the next day if I could come more often.

The Gentle Author – Did you know the history already?

Maurice – I’d already got the background you see. I went home and said to my wife, ‘They want me to come more often, and she said, ‘Well, why can’t you?’ She was younger than me and was keeping me in the state of life that I wanted. She was kind. She only made one mistake in her life but there we are. She put up with it and suffered me for forty years!

The Gentle Author – Were you the mistake?

Maurice – Yes!

The Gentle Author – Why have you stuck with St Paul’s?

Maurice – After the Dean asked me and my wife said, ‘Of course you can,’ I took it on and for twenty-odd years I did all the school visits to the cathedral. But eventually they decided that the modern idea was to have an education department which meant they wanted a full-time paid person. I had been working twenty years for nothing and, because I worked for nothing, I enjoyed it – I didn’t have to worry what the other people thought. So I wouldn’t have put in for the new job and, fortunately, the headmaster at the Cathedral School said, ‘If they don’t want you, you can come here every day.’ So then I moved to working in the school.

The Gentle Author – Were you teaching?

Maurice – Helping out in various ways, especially hearing children read and going with the boys to watch them play football and cricket. For the last fifteen years I went every day, until eighteen months ago when I decided to cut it down and now I only go on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. But the little children make a fuss of me.

The Gentle Author – How are you involved with the cathedral?

Maurice – In the morning I’m in the Cathedral School but then, after school lunch, I help in the library. One of my jobs is to ensure that we have two copies of every service, I put them all in order and file them away. I look up letter queries for the librarian. When people write to say, ‘I believe my great grandfather was in the choir at St Paul’s,’ I go through the records. Usually they hadn’t, they had sung here but with a visiting choir probably.

The Gentle Author – Do you know the collection well?

Maurice – Oh yes, many years ago the librarian decided we ought to have a list of all the books. And so, in my spare time, for about five years I wrote down on sheets of paper all the books. The ones in Greek were difficult, I just had to copy the alphabet. Those records are kept and the librarian still consults them today.

The Gentle Author – That’s a big achievement.

Maurice – I was lucky I had a librarian who chased me around in good fun and called me rude things, saying, ‘Get some overalls on you lazy so-and-so and get some work done!’

The Gentle Author – Do you like the cathedral?

Maurice – It’s given me a great deal. I’ve walked with school parties up to the top of the dome at least two thousand times, but I can’t do it any longer.

The Gentle Author – When was the last time you went up on top?

Maurice – Oh, probably five years ago. I’ve only become an invalid in the last two to three years really.

The Gentle Author – You don’t seem like an invalid.

Maurice – I’m wearing out. It’s hard work now – I have to make myself come here whereas I used to be dashing here. When I was a schoolteacher, I knew how many days before the next holiday. But here, when the school says they’re away for three weeks, ‘Oh,’ I say, ‘I’m going to miss you. And the school lunch!’

The Gentle Author – Do you have any opinions about Wren’s architecture?

Maurice – Only insofar as I’ve read so much about it that I realise, in my lack of knowledge, what a wonderful person Wren was to do what he did, despite all the handicaps that he was up against.

The Gentle Author – What kind of man do you think Christopher Wren was?

Maurice – Well, he was so gifted at so much, you see, he was brilliant not just in one subject but in many things. And he persisted in what he wanted, even though it wasn’t always easy for him financially. He was a marvellous person to have done it and I realise it was 300 years ago, you know.

The Gentle Author – Three times your lifetime.

Maurice – That’s right and a lot has changed in my lifetime, so 300 years ago it was very different…

The Gentle Author – What do you think are the big changes in your lifetime?

Maurice – One of the biggest is computers, and now I realise my day is up. If I sit on the tube in the morning, if there are a dozen people – six here, six there – nine of them are playing with these tablets and phones. I’m not talking to anybody you see!

The Gentle Author – It’s rare to meet someone so senior, so I want to ask what have you learned in your life?

Maurice – I’ve learnt from experience how wonderful it can be to have sensible friends and a sensible upbringing and a perfect wife. My parents were strict insofar as we were told what was right and what was wrong. ‘I’d rather your hand was cut off than you stole something,’ my mother would say.

I learnt to live – I think – a full life. I’ve enjoyed my sport. How fortunate I have been in life that I have been pushed to do things rather than had ambition. I have no ambition.

When I was ending my time in the Royal Navy a colleague who was a schoolteacher said, ‘When the war is over you would make a good schoolteacher,’ and I said, ‘Of course I wouldn’t – my schoolteachers would laugh if you said that.’ But when the war was over, they were so short of male teachers, they were willing to take almost anybody. The result was my mate made me fill out a form – he pushed me and I became a teacher.

Every Christmas, I hear from about two dozen of my pupils of fifty years ago. When I go to watch cricket at the Oval when the season starts, one of my pupils of 1959, he’ll be there saying, ‘Oh you’re still breathing! We prayed for you every night and you always turned up in the morning despite our prayers!’

(Transcript by Rachel Blaylock)

Maurice Sills (1915-2017)

James Leman’s Album Of Silk Designs

Join me next Saturday here in the 300-year-old withdrawing room at the Townhouse in Fournier St for tea, and cakes freshly baked to a recipe of 1720, at the conclusion of The Gentle Author’s Tour of Spitalfields.

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

The oldest surviving set of silk designs in the world, James Leman’s album contains ninety ravishingly beautiful patterns created in Steward St, Spitalfields between 1705 and 1710 when he was a young man. It was my delight to visit the Victoria & Albert Museum and study the pages of this unique artefact, which is the subject of an interdisciplinary research project under the auspices of the V&A Research Institute, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Leman Album offers a rare glimpse into an affluent and fashionable sphere of eighteenth century high society, as well as demonstrated the astonishing skill of the journeyman weavers in East London three hundred years ago.

James Leman (pronounced ‘lemon’ like Leman St in Aldgate) was born in London around 1688 as the second generation of a Huguenot family and apprenticed at fourteen to his father, Peter, a silk weaver. His earliest designs in the album, executed at eighteen years old, are signed ‘made by me, James Leman, for my father.’ In those days, when silk merchants customarily commissioned journeyman weavers, James was unusual in that he was both a maker and designer. In later life, he became celebrated for his bravura talent, rising to second in command of the Weavers’ Company in the City of London. A portrait of the seventeen-twenties in the V&A collection, which is believed to be of James Leman, displays a handsome man of assurance and bearing, arrayed in restrained yet sophisticated garments of subtly-toned chocolate brown silk and brocade.

His designs are annotated with the date and technical details of each pattern, while many of their colours are coded to indicate the use of metallic cloth and different types of weave. Yet beyond these aspects, it is the aesthetic brilliance of the designs which is most striking, mixing floral and architectural forms with breathtaking flair in a way that appears startling modern. The Essex Pink and Rosa Mundi are recognisable alongside whimsical architectural forms which playfully combine classical and oriental motifs within a single design. The breadth of James Leman’s knowledge of botany and architecture as revealed by his designs reflects a wide cultural interest that, in turn, reflected flatteringly upon the tastes of his wealthy customers.

Until recently, the only securely identified woven example of a James Leman pattern was a small piece of silk in the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia. Miraculously, just as the V&A’s research project on the Leman Album was launched, a length of eighteenth-century silk woven to one of his designs was offered to the museum by a dealer in historical textiles, who recognised it from her knowledge of the album. The Museum purchased the silk and is investigating the questions that arise once design and textile may be placed side by side for the first time. With colours as vibrant as the day they were woven three hundred years ago, the sensuous allure of this glorious piece of deep pink silk adorned with elements of lustrous green, blue, red and gold shimmers across the expanse of time and is irresistibly attractive to the eye. Such was the extravagant genius of James Leman, Silk Designer.

On the left is James Leman’s design and on the right is a piece of silk woven from it, revealing that colours of the design are not always indicative of the woven textile

The reverse of each design gives the date and details of the fabric and weave

Portrait of a Master Silk Weaver by Michael Dahl, 1720-5 – believed to be James Leman

All images copyright © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

With grateful thanks to: Dr Olivia Horsfall Turner, Senior Curator of Designs – Dr Victoria Button, Senior Paper Conservator – Clare Browne, Senior Curator of Textiles – Dr Lucia Burgio, Senior Scientist and Eileen Budd, V&A Research Institute Project Manager

You may also like to read about

The Principal Operations of Weaving

At Anna Maria Garthwaite’s House

Anna Maria Garthwaite, Silk Designer

At Mile End Place

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

Mrs Johnson walks past 19 Mile End Place

Whenever I walk down the Mile End Rd, I always take a moment to step in through the archway and visit Mile End Place. This tiny enclave of early nineteenth century cottages sandwiched between the Velho and the Alderney Cemeteries harbours a quiet atmosphere that recalls an earlier, more rural East End and I have become intrigued to discover its history. So I was fascinated when Philip Cunningham sent me his pictures of Mile End Place from the seventies together with this poignant account of an unspoken grief from the First World War, still lingering more than fifty years later, which he encountered unexpectedly when he moved into his great-grandparents’ house.

“In 1971, my girlfriend – Sally – & I moved from East Dulwich to Mile End Place. It was number 19, the house where my maternal grandfather – Jack – had been born into a family of nine, and we purchased it from my grandfather’s nephew Denny Witt. The house was very cheap because it was on the slum clearance list but it was a lot better than the rooms we had been living in, even with an outside toilet and no bath.

There were just two small bedrooms upstairs and two small rooms downstairs. In my grandfather’s time, the front room was kept immaculate in case there might be a visitor and the sleeping was segregated, until Uncle Harry came back from the Boer War when he was not allowed to sleep with the other boys. For reasons left unexplained, he was banished to the front room and told he had better get married sharpish – which he did.

I first met my neighbour Mrs Johnson when gardening in the front of the house. I said ‘Morning,’ but there came no reply.‘What a nasty woman’ I thought, yet worse was to come. Mrs Johnson lived at the end of the street and two doors away lived a vague relative of hers who was married to an alcoholic. ‘She picked ‘im up in Jersey,’ I was told. He drank half bottles of whisky and rum, and threw the empties into the graveyard at the back of our houses – sometimes when they were half full.

I would often go to our outside toilet in socks and, on one occasion, nearly stepped upon pieces of broken glass that had been thrown into our backyard. At first, I assumed it was Paul – the graveyard keeper – and went straight round to his house in Alderney St. I nearly knocked his door down and was ready to flatten him, until he became very apologetic and explained that Mrs Johnson had told him we were students and always having parties. True in the first count, lies in the second. Mrs Johnson knew quite well who the culprit was, as did the everyone else in street. I was still angry, so I threw the glass back where it came from – which must have been a real chore to clear up on the other side

Sometime after all these events, Jane Plumtree – a barrister – moved into the street. She said ‘We must have street parties!’ and so we did. At the first of these, the longest established families in the street all had to sit together and – unfortunately – I was sat next to Mrs Johnson. She hissed and fumed, and turned her back on me as much as she could, until suddenly she turned to face me and said, ‘I knew your grandfather J-a–c—k, he came b-a–c—k!’ She spat the words out. I did not know what she was talking about so I just said, ‘Yes, he was a drayman.’

Later, I reported it over the phone to my Auntie Ethel. ‘Oh yes,’ she explained, ‘Mrs Johnson had three brothers and, when the First World War broke out, they thought it was going to be a splendid jolly. They signed up at once, even though two were under-age, and they were all dead in three months.’ Unlike my grandfather Jack, who came back.

Jack was married and living in Ewing St with his five children, but he was called up immediately war was declared because had been in the Territorial Army. He was present at almost every major piece of action throughout the First World War and, at some point, while driving an ammunition lorry, he got into the back and rolled a cigarette when there was no one around. He got caught and was sentenced to be shot, but – fortunately – someone piped up and declared they did not have enough drivers, so his punishment was reduced to six weeks loss of pay, which made my grandmother – to whom the money was due – furious!

When Jack and the other troops with him came under fire in a French village, he and an Irish soldier broke into a music shop for cover. On the wall was a silver trumpet which Jack grabbed at once, but his Irish companion grabbed the mouthpiece and would not let Jack have it unless he went into the street, amid the falling shells, to play. Reluctantly, Jack did this – playing extremely fast – and he brought the trumpet home with him to the East End.”

19 Mile End Place

19 Mile End Place

Philip’s grandfather Jack was born at 19 Mile End Place

View from 19 Mile End Place

Philip purchased 19 Mile End Place from his cousin Danny Witt, photographed during World War II

Outside toilet at 19 Mile End Place

Backyard at 19 Mile End Place

View towards the Alderney Cemetery with the keeper’s house in the distance

Paul Campkin, the Cemetery Keeper

The Alderney Cemetery

Looking out towards Mile End Rd

Entrance to Mile End Place from Mile End Rd

Photographs copyright © Philip Cunningham

You may also like to read about