Up the tower with Rev Turp

Who would have dreamed there was as much as two hundred and fifty tons of ironwork inside the tower of George Dance’s St Leonard’s Shoreditch? This edifice, completed in 1740, does not impose itself monumentally upon the High Street, and yet, comprising seventeen hundred tons of masonry, with walls eleven feet thick, it is as awe-inspiringly vast a structure as any parish church tower could be – as I discovered for myself, when I had the privilege of a guided tour by Reverend Paul Turp that led me up and up and up.

Following in the Rev Turp’s footsteps – picking up where we left off at the end of my subterranean adventure at St Leonard’s – I walked into the entrance of the church and slipped through the narrow door to the tower, next to the seventeenth century stocks and whipping post. Ascending the cramped stone staircase in the thickness of the wall, spiralling upwards towards the ringers’ chamber, I could not resist poking my head round the door of the dark and dusty room behind the clockface. As with the space beyond the cinema screen, there is an intriguing enigma about the hidden world behind the clock, like standing inside an eye, with external vision obscured by the single image upon the lense.

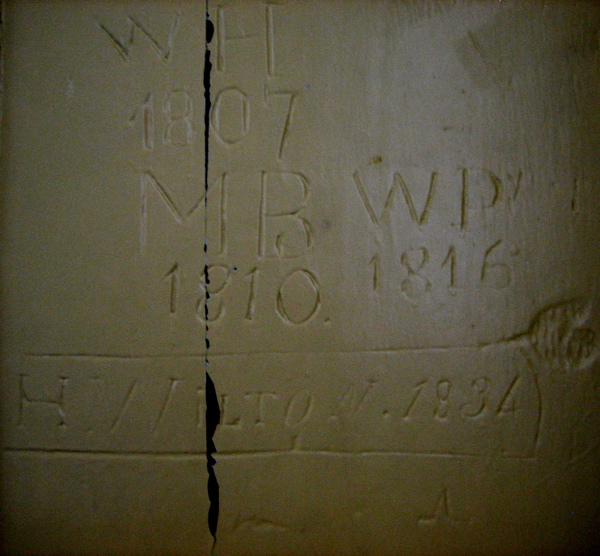

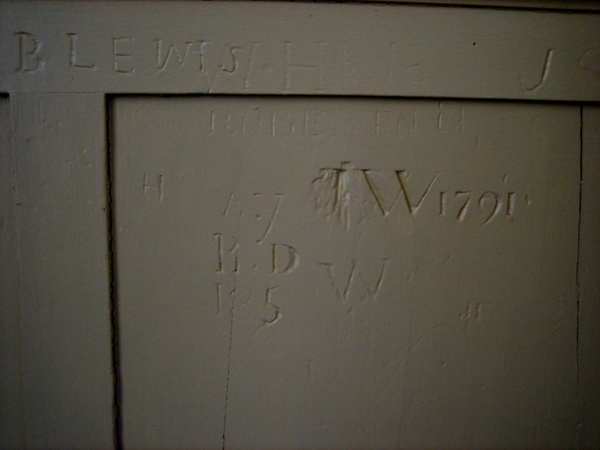

While Rev Turp expounded enthusiastically about his magnificent thirteen bells, named after the twelve apostles plus Andrew and rung more than any other church bells in the South East of England thanks to a set of shutters that spare the neighbours from the clamor, my eyes wandered to explore the eighteenth and nineteenth century graffiti upon the panelling. Men’s names and initials were incised in confident block or italic letters. There is nothing furtive about these carvings, suggesting those responsible were bellringers or other church officials, confident of their right to be here and leave modest inscriptions for perpetuity.

Ascending further up the spiral staircase, we came to the place where the stone steps ended at the foot of a metal ladder leading into the steel bell frame itself. Here we stood upon a grid of hefty iron girders from which the bells hang, each mounted upon a massive wheel, turned by ropes pulled in the chamber below. Now, it was as if we were interlopers within the workings of a giant clock, dwarfed by ranks of wheels and gleaming bells on either side. This is where Rev Turp lowered his voice to issue a warning – explaining that there was no obligation to go any further – and when I saw the narrow old wooden ladder roped in place, ascending diagonally across the space, it did cause me to think twice. “I don’t want you falling and damaging my bells,” declared the Rev, wagging his finger with droll humour, before setting a bold example by clambering swiftly up the precarious ladder with the unique confidence of one who has a special relationship with the almighty.

Inspired by the Rev’s example, I set out confidently upon the ladder too, only to find myself unexpectedly in a vast dark chimney, standing upon a few planks creating a makeshift platform within the bare internal shaft of the tower. Here I made the mistake of looking down through the floor to the bell frame far below. I did not want to fall and damage the Rev Turp’s bells. Recovering myself, I discovered another ladder in the gloom leading upwards to a square of daylight where the Rev Turp stood, like St Peter, waiting to greet me with a welcoming hand, once I had transcended the final level. Concentrating on holding the rungs firmly, as the Rev taught me, so that if one should break I could hold my own weight and my hands would not slide down the slides, I climbed safely to the top of the ladder.

Just as in those fairground rides which induce an accumulation of tension only to deliver a powerful rush once the pinnacle is reached, I was exhilarated to arrive at the top of the tower and look out across the expansive roofscape of Shoreditch, with Spitalfields and the City of London beyond. Where a moment before, I was gripped with a sense of my own vulnerability, now I could survey my fellow humans as if they were ants beneath my feet. The new overland rail line, so many years in construction, was a mere toy for our amusement from up here. “Look there goes a train!” pointed out the Rev in childlike delight.

Yet the humbling evidence of greater forces was here in the lumps of grey shrapnel, some as large as potatoes, buried in the stonework at the very top of the tower. The blast of World War II bombs was sufficient to propel debris to this height and embed them in stone. Changing tone, the Rev described how during the burning of London, the heat was so great that people took refuge in the crypt to escape the flames of Shoreditch High St. When he was a young priest, Reverend Paul Turp spent many hours up here in this eyrie (explaining his nimble confidence within the tower today), from whence he surveyed his whole parish, learning more about his community from this vantage point, because the physical composition and social contrasts of the neighbourhood are more apparent from above than at street level.

Returning to earth again, my legs turned to jelly, briefly unaccustomed to merely walking upon the pavement. In spite of the insights Rev Turp had granted me, I was relieved to be back, because I am not a burrowing creature that feels comfortable under the ground, nor am I a fowl that can soar effortlessly up into the sky, but one that delights to walk with my own two feet upon the plain surface of the earth.

World War II shrapnel embedded in the stone at the top of the tower.

Shoreditch High St from above, looking towards the Barbican.

Graffiti in the bell ringers’ chamber.

I will leave a very obvious comment … that post was breath taking! Thank you for climbing that tower’s ladders, one rung at a time. And for taking along your camera. I am sure that my hands would have been too shaky to get the wonderful photos that you have shared with your readers.

Somehow, I had never before thought about shrapnel being inbedded in stone, although I certainly should have done. The views within the tower, including those carvings, were magnificent. The view from the tower’s top … well, again I thank you.

Best wishes.

Just imagining climbing up there put the fear of God in me! You are not only a delightful guide, but brave as three bears to boot…

But where was the Rev. Smallbone? I think we should be told.

Best wishes,

Joan

I echo your other comments, far better you than I climbing that ladder! But loved the view since you were kind enough to share it.